Diamantinasaurus

| Diamantinasaurus Temporal range: Late Cretaceous, 93.9 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

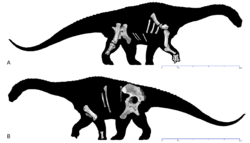

| Holotype skeleton in (a) right and (b) left views | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Order: | Saurischia |

| Suborder: | †Sauropodomorpha |

| Clade: | †Neosauropoda |

| Clade: | †Macronaria |

| Clade: | †Titanosauria |

| Family: | †Antarctosauridae |

| Genus: | †Diamantinasaurus Hocknull et al., 2009 |

| Species: | †D. matildae |

| Binomial name | |

| Diamantinasaurus matildae Hocknull et al., 2009 | |

Diamantinasaurus is a extinct genus of lithostrotian titanosaurian sauropod from Australia that lived during the early Late Cretaceous, about 94 million years ago. The type species of the genus is D. matildae, first described and named in 2009 by Scott Hocknull and colleagues. Meaning "Diamantina reptile", the name is derived from the location of the nearby Diamantina River and the Greek word sauros, "reptile". The specific epithet is from the Australian song Waltzing Matilda, also the locality of the holotype and paratype. The known skeleton includes most of the forelimb, shoulder girdle, pelvis, hindlimb and ribs of the holotype, and one shoulder bone, a radius and some vertebrae of the paratype.

History of discovery

The holotype of Diamantinasaurus was first uncovered over four seasons of excavations near Winton, Queensland, Australia. The bones, found alongside the holotype of Australovenator and crocodylomorphs and molluscs.[1] The two dinosaurs found, known from specimens catalogued as AODF 603 and 604 were described in 2009 by Scott Hocknull and his colleagues. Specimen AODF 603 became the basis for the genus Diamantinasaurus, and the species D. matildae. The species name is a reference to the song "Waltzing Matilda", written by Banjo Paterson in Winton, while the generic name is derived from the Diamantina River, running nearby the type locality combined with the Greek sauros, meaning "lizard". AODF 603, the holotype, includes the right scapula, both humeri, right ulna, both incomplete hands, dorsal ribs and gastralia, partial pelvis, and the right hindlimb missing the foot.[2] The paratype, under the same specimen, includes dorsal and sacral vertebrae, the right sternal plate now thought to represent the remainder of a coracoid, a radius, and one manual phalanx. All these bones come from AODL 85, nicknamed the "Matilda Site" at Elderslie Sheep Station, located about 60 km (37 mi) west-northwest from Winton in central Queensland. This locality is in the upper midsection of the Winton Formation, which dates to the Cenomanian of the Late Cretaceous.[1][2]

The discovery of Diamantinasaurus ended a pause in the discovery of new dinosaurs in Australia, as the first sauropod named in over 75 years. Along with Australovenator, Diamantinasaurus has been nicknamed after the Australian song "Waltzing Matilda", with Australovenator being called "Banjo" and Diamantinasaurus being nicknamed "Matilda". Wintonotitan, also from the site, was dubbed "Clancy".[3][4] The find was apparently the largest dinosaur discovery in Australia that was documented since that of Muttaburrasaurus in 1981.[4]

An additional specimen, AODF 836, was described in 2016. It includes portions of the skull, including a left squamosal, nearly complete braincase, right surangular, and various fragments. Additionally, the specimen also includes the atlas, axis, five other cervical vertebrae, three dorsal vertebrae, additional dorsal ribs, portions of the hip, and another right scapula.[5]

Description

Diamantinasaurus was a relatively small for a titanosaurian, possibly reaching 15–16 m (49–52 ft) in length and 15–20 t (17–22 short tons) in weight. Some of its relatives are known possessed armour osteoderms although is it unknown whether Diamantinasaurus had these.[3] Like other sauropods, Diamantinasaurus would have been a large quadrupedal herbivore.[6] Since the original description, the only major revisions include the misidentification of the "sternal plate", misplacement of manual phalanges III-1 and IV-1 as III-1 and V-1 respectively, and the identification of the missing portion of the fibula.[1]

Classification

When it was originally described, Diamantinasaurus was assigned to Lithostrotia incertae sedis. In both phylogenies it was placed in, Diamantinasaurus was either just outside Saltasauridae or the sister taxon of Opisthocoelicaudia within the family.[2] In a 2014 study, it was found that the genus was placed as a lithostrotian in both large phylogenies, in a relatively derived position in Titanosauria. Their first phylogeny was modified from that of Carbadillo and Sander (2014), the matrix being indirectly based on Wilson's 2002 phylogeny. In that cladogram, Diamantinasaurus was found to be sister taxon to Tapuiasaurus, their relationship outside of Saltasauridae. In this phylogeny, the Bremer support for each group was at most 1. Five features of the skeleton supported the placement of Diamantinasaurus in Lithostrotia.[1]

| Somphospondyli |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

In the same study, the relationships using the Mannion et al. (2013) matrix were tested. These resolved with Diamantinasaurus as a saltasaurid, sister to Opisthocoelicaudia, with Dongyangosaurus as the next closest. Two characters were found to support the placement of Diamantinasaurus in Lithostrotia, and a third could not be evaluated.[1]

Another phylogenetic analysis in 2016, partially reproduced below, found it as a non-lithostrotian titanosaur and the sister taxon of the contemporary Savannasaurus.[5][7]

| Titanosauria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

Paleobiology

Growth

In 2011, the smallest positively identified titanosaur embryo was described. Although it was uncovered in Mongolia, the embryo shares the most features with Diamantinasaurus and Rapetosaurus. The embryo, from a relatively spherical 87.07–91.1 millimetres (3.428–3.587 in) egg, was identified as persisting to a lithostrotian. The embryo was slightly robust, intermediate between the robustness of Rapetosaurus and Diamantinasaurus. The egg is part of an entire nesting site for lithostrotian titanosaurs. Dating of the region also suggests that this egg predates those of Auca Mahuevo, and the eggs were laid in the Early Cretaceous.[8]

Paleoecology

Diamantinasaurus was found about 60 kilometres (37 mi) northwest of Winton, near Elderslie Station.[2] It was recovered from the fossil-rich section of the Winton Formation, which can be dated to approximately 93.9 million years ago.[9] Diamantinasaurus was found in a clay layer between sandstone layers, interpreted as an oxbow lake deposit. Also found at the site was Australovenator, which was directly associated with Diamantinasaurus, bivalves, fish, turtles, crocodilians, and various plants. The Winton Formation had a faunal assemblage including bivalves, gastropods, insects, the lungfish Metaceratodus, turtles, the crocodilian Isisfordia, pterosaurs, and several types of dinosaurs, such as the aforementioned Australovenator, the sauropods Wintonotitan, Savannasaurus, and Austrosaurus, and unnamed ankylosaurians and hypsilophodonts. Diamantinasaurus bones can be distinguished from other sauropods because of the overall robusticity as well as multiple specific features. Plants known from the formation include ferns, ginkgoes, gymnosperms, and angiosperms.[2]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Poropat, S.F.; Upchurch, P.; Mannion, P.D.; Hocknull, S.A.; Kear, B.P.; Sloan, T.; Sinapius, G.H.K.; Elliot, D.A. (2014). "Revision of the sauropod dinosaur Diamantinasaurus matildae Hocknull et al. 2009 from the mid-Cretaceous of Australia: Implications for Gondwanan titanosauriform dispersal". Gondwana Research. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2014.03.014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hocknull, Scott A.; White, Matt A.; Tischler, Travis R.; Cook, Alex G.; Calleja, Naomi D.; Sloan, Trish; Elliott, David A. (2009). Sereno, Paul, ed. "New Mid-Cretaceous (Latest Albian) Dinosaurs from Winton, Queensland, Australia". PLoS ONE. 4 (7): e6190. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0006190. PMC 2703565

. PMID 19584929.

. PMID 19584929. - 1 2 Musser, A. (2010-06-03). "Animal Species: Diamantinasaurus matildae". Australian Museum.

- 1 2 "New dinosaurs found in Australia". BBC News. 2009-07-03.

- 1 2 Poropat, S.F.; Mannion, P.D.; Upchurch, P.; Hocknull, S.A.; Kear, B.P.; Kundrát, M.; Tischler, T.R.; Sloan, T.; Sinapius, G.H.K.; Elliott, J.A.; Elliott, D.A. (2016). "New Australian sauropods shed light on Cretaceous dinosaur palaeobiogeography". Scientific Reports. 6: 34467. doi:10.1038/srep34467.

- ↑ Upchurch, P.; Barrett, P.M.; Dodson, P. (2004). "Sauropoda". In Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmolska, Halszka. The Dinosauria (Second ed.). University of California Press. pp. 259–322. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- ↑ St. Fleur, Nicholas (20 October 2016). "Meet the New Titanosaur. You Can Call It Wade.". New York Times. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- ↑ Grellet-Tinner, G.; Sim, C.M.; Kim, D.H.; Trimby, P.; Higa, A.; An, S.L.; Oh, H.S.; Kim, T.J.; Kardjilov, N. (2011). "Description of the first lithostrotian titanosaur embryo in ovo with Neutron characterization and implications for lithostrotian Aptian migration and dispersion". Gondwana Research. 20 (2-3): 621–629. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2011.02.007.

- ↑ Tucker, R.T.; Roberts, E.M.; Hu, Y.; Kemp, A.I.S.; Salisbury, S.W. (2013). "Detrital zircon age constraints for the Winton Formation, Queensland: Contextualizing Australia's Late Cretaceous dinosaur faunas". Gondwana Research. 24 (2): 767–779. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2012.12.009.

| Wikinews has related news: Three new dinosaurs discovered in Australia |