Devipuram

| Devipuram | |

|---|---|

|

Sahasrakshi Meru Temple | |

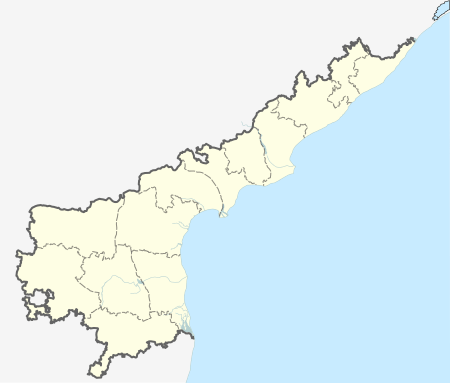

Devipuram Location within Andhra Pradesh | |

| Name | |

| Devanagari | देवीपुरम् |

| Sanskrit transliteration | Devīpuram |

| Telugu | దేవీపురం |

| Geography | |

| Coordinates | 17°45′55.32″N 83°4′58.64″E / 17.7653667°N 83.0829556°ECoordinates: 17°45′55.32″N 83°4′58.64″E / 17.7653667°N 83.0829556°E |

| Country | India |

| State | Andhra Pradesh |

| District | Visakhapatnam |

| Culture | |

| Primary deity | Shakti as Sahasrakshi |

| Architecture | |

| Architectural styles | South Indian Architecture |

| Number of temples | 4 |

| History and governance | |

| Date built | 1985-1994 |

| Creator | N. Prahalada Sastry |

| Website | devipuram.com |

Devipuram is a Hindu temple complex located near Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh, India. Belonging primarily to the Shakta school of Hinduism, it is dedicated to the goddess Sahasrakshi (lit., "she who has a thousand eyes", a form of Lalita Tripurasundari or Parvati), and her consort Kameshwara (a form of Shiva).

Overview

Devipuram's primary focus is the Sahasrakshi Meru Temple, a unique three-story structure built in the shape of a Sri Meru Yantra; i.e., a three-dimensional projection of the sacred Hindu diagram known as Sri Chakra, which is central to Srividya upasana (an ancient and intricate form of Tantric Shakta worship). Measuring 108 feet (33 m) square at its base and rising 54 feet (16 m) high, the temple has become an increasingly popular pilgrimage destination over the past decade. Two other shrines, the Kamakhya Peetham and Sivalayam, are located on hills adjacent to the main temple.

The sanctum sanctorum of the Sahasrakshi Meru Temple is reached by circumambulating inward and upward, past more than 100 life-sized murthis of various shaktis or yoginis (deities expressing essential aspects of the Devi) who are, in Srividya cosmology, said to inhabit and energize the Sri Chakra. Their exact locations are "mapped" in an elaborate ritual called the Navavarana Puja ("Worship of the Nine Enclosures"), which was in turn condensed into a mantric composition called the Sri Devi Khadgamala Stotram ("Hymn to the Auspicious Goddess's Garland of Swords"), forming the basis of the temple's layout.

This temple is unconventional in its practice of allowing devotees to perform puja to the Devi themselves, without regard to caste, creed or gender.[1] This may be an emulation of the Kamakhya temple complex in Assam, which has the same open policy for worship. The fact that many of the temple's murthis are portrayed as "sky-clad," or nude, has also, over the years, gained Devipuram considerable attention.[2]

History

Construction of the Sahasrakshi Meru Temple in Devipuram began in 1985, and its completion and consecration (kumbha-abhishekam) took place in 1994. In accordance with Hindu tradition, the temple was re-consecrated for its twelfth anniversary in February 2007.

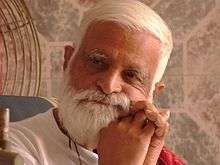

The founder of Devipuram is Dr. N. Prahalada Sastry (1934-2015), a former university professor and nuclear physicist who left a successful 23-year career with the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research in Mumbai to begin work on the Devipuram temple in 1983. Now a noted spiritual guru, better known as Sri Amritananda Natha Saraswati (and generally addressed as "Guruji"), Sastry reports that his creation of Devipuram was based on several visions of the Divine Mother, which specified both the design and mission of the temple complex. Each of the many murthis within the Sahasrakshi Meru Temple was individually sculpted to Sastry's specifications, physically manifesting his meditative visions of these deities.

According to Devipuram's official history: "In 1983, during Devi Yajna, Guruji was approached by the brothers of the Putrevu family with a request to build a temple for the Divine Mother. In addition to the 3 acres (12,000 m2) of land that they had donated, Guruji bought the adjoining 10 acres (40,000 m2) and it was registered as land for the Devi temple."[3] The history continues:

"Having acquired the land, Guruji was looking for divine guidance, a sign of approval to commence construction of the temple. In the vicinity of the donated land, there was a small hillock where Guruji would often spend time in meditation. On the slopes of the hillock, he noticed a formation [i.e., a cleft rock forming a natural yoni] very similar to that of the Kamakhya Peetam in Assam. One day while in meditation he experienced himself lying on the peetam [holy site], while four others performed a homa, with flames emanating from his body. And during purnahuthi [the final round of ritual offerings], he felt a heavy object being placed on his heart. Awakening from his meditative state, Guruji was prompted to dig that site. Unearthed from that very spot, he found a Sri Chakra Maha Meru made of panchaloha. It was later discovered that a huge yajna had been performed in that area more than 250 years earlier."[3]

Soon afterward, "Guruji had visions of the Devi as a 16-year-old girl. With her blessings, he built the Kamakhya Peetam on the hillock and a Siva temple on the peak in 1984. Construction of the Sahasrakshi Meru Temple in Devipuram was started in 1985."[3] A recent Devipuram publication reflected, "Even a fleeting glance at what has been accomplished around what used to be a no-man's land is enough to astound anyone." [4]

Mission & Activities

In addition to providing regular religious services and other spiritual functions, Devipuram produces and distributes spiritual aids (most specifically related to Srividya upasana), such as high-precision Meru yantras,[5] animated presentations, audio/video aids and other educational materials for spiritual aspirants.

Devipuram has also become a hub for spiritual and rural empowerment workshops and seminars. For this purpose, Sastry founded the Sri Vidya Trust, a not-for-profit, non-governmental organization headquartered at Devipuram. Through the trust, Sastry – along with other staff and volunteers at Devipuram – has undertaken a number of developmental initiatives focused on non-formal education, empowerment of women and low-cost housing for the rural poor. A cooperative thrift society, sponsored by the trust and called Jagruti, offers micro-financing services to local villagers. Low-cost, fire-retardant, geodesic dome-houses for pilgrims and other visitors have been erected at Devipuram, using appropriate technologies to demonstrate the viability of such designs in rural India. Devipuram has also conducted many rural empowerment programs in the surrounding countryside, relating to health, hygiene, family planning, literacy, energy generation and energy conservation. [6]

Future plans

In furtherance of Sastry's vision, Devipuram has ambitious plans to become a "global resource for goddess worship."[7]

In 2005, news reports noted that a spiritual retreat would be developed at Devipuram.[8] In 2010, as part of that development, the Sri Villa guest house was completed, featuring rooms of many sizes, a large cafeteria, an event hall accommodating 200 plus several smaller halls, and air-conditioned suites for families.[9] In 2013, at age 78, Sastry announced that, upon his departure or passing, "Devi's padukas [symbolic of the goddess] will be in charge of Devipuram, not any human being. There will be no more peethadhipatis [human spiritual leaders] here; only administrators of the Sri Vidya Trust to look after all matters concerning Devipuram."[10]

Social Significance

Devipuram has remarkable high female involvement. The participation of women in Devipuram is largely due to the weakening of India’s caste and kin communities, which is a result of rapid urbanization. This social shift leads, for some individuals, to a loss of dharma and an introduction of anomie in its place. Devipuram relieves anomie by creating a community which empowers women to thrive within self-determined social roles.

Explaining his female-focused worship, Guruji said, “In western religions, like Islam or Christianity, the god is a father. However, Hinduism has both a mom and a dad. First comes the mom [in power and authority], then the dad, and then beneath him is the Guru… In the literature and in spirit Hinduism is mother oriented, but in life experiences, it is more commonly father oriented.” Guruji felt he had been instructed by the goddess to lead a spiritual revolution by returning Hindu worship to focusing on and learning from the goddess.

This belief, spread by adherents of Devipuram, that the mother goddess is the preeminent deity within Hindu dogma inspires many women to realize their own autonomy. Through learning about and worshiping Devi, women understand that they can create homes that are mother oriented and that they can be respected as leaders within their social unit. Women find themselves empowered by the new identity Devipuram provides, an identity which they need in their rapidly changing world.

Indians traditionally define themselves by caste and kin. For generations, these identifiers determined a person’s marriage, residence, religion, and diet. This normative social system, argued anthropologists Rudolph and Rudolph, was disrupted when modern technologies like the railroad and telegraph were introduced by British colonials and effectively “[destroyed] village isolation” (1967, p. 22). In 1901, only 11.4% of India’s population lived in urban centers (Singh, 1978). By 2001, just one hundred years later, 28.5% of the population was living in an urban setting. Today, over 32% of India’s population lives in cities (2015, Central Intelligence Agency). Rapid urbanization in India strained, altered, and in some cases destroyed the social systems of individuals, especially as it broke apart multi-generational households. This breakdown of social solidarity resulted for some individuals in anomie.

The sociologist Emile Durkheim theorized that there are two types of social solidarity: mechanical, in which people are united through their uniformity of purpose and activity, and organic, in which unity is formed through social interdependence. The term anomie is derived from a Greek word meaning “without law”. Anomie comes into play when society, and the individuals within it, are in a state of transition from mechanical to organic solidarity, generally in response to a large scale social change like urbanization. During this transition, people find themselves lacking social laws to follow. They no longer know to what group or entity they should look to for their social norms. This displacement causes anomie.

Indian women are especially subject to anomie. Within the multi-generational household women know what their dharma is and how to fulfill it. Dharma is a Hindu term that means duty, or the role a person must fill in life to progress spiritually. A traditional Hindu woman's dharma is to marry and to raise children, preferably sons, within the framework of a multi-generational household. They lose this sure social role, however, when transplanted into a nuclear home. It is interesting to note that the majority of active participants in Devipuram are urban women with children school-age and above, and with a high economic status that keeps them out of the work force. While many women who move to an urban setting must go to work to help provide for their family, and thus have resolved or are resolving anomie by engaging in organic solidarity, the women of Devipuram have not entered into that world and so are trapped in the anomie that was created when they left mechanical solidarity behind.

Most women who live in urban India are raised to function within the multi-generational household, with its own community of women inherent to it. The social norms, roles, and laws that these women are taught while growing up are designed to facilitate their success in this specific environment. However, when removed from this social structure upon entering into an urban, nuclear setting, the woman is abruptly left without a community and social laws. She does not know her own role in this new system. No longer attached to the higher aims of their kinship group, she finds herself in a state of lawlessness without any tools provided to resolve her anomie. Devipuram promises women a new social group, with its own laws and greater-than-self purpose to which they can attach themselves. Thus, it promises them relief from anomie.

The ultimate symbol worshipped in Devipuram is the Sri Chakra, a yantra which represents the palace of the goddess Devi. The goddess resides in the central chamber of the palace, but many other gods and goddesses also reside in this yantra. Thus, even more than providing a home for Devi and an idol through which Hindus can worship her, this yantra teaches that while there are many aspects of the divine, the gods are ultimately all one entity. Devi is a whole entity, comprising every god and living within every deity. Through their study of the Sri Chakra, devotees learn that they and their peers are, like the gods, all one. They learn that Devi lives in them as well as in everyone around them. A common saying among devotees is “I am Devi, you are Devi”, and this belief is central to maintaining the new social system Guruji instigated by way of Devipuram.

The Sri Chakra is worshiped through the Naravahana ritual. It is important to note that this puja is always done among a large group. Both the set-up and performance of the ritual demand substantial time and effort, so that the Naravahana naturally creates a shared experience for members present. The Naravahana is both a symbol of community and an experience of community-building in its own right. By the unity it both represents and demands through its practice, it inherently promotes inclusion of others, female leadership and ownership of activity, and an element of teaching and serving one another.

Durkheim argued that anomie is found within an individual’s transition from mechanical to organic solidarity, and is escaped when this transition is successfully completed. The women who adhere to Devipuram, however, have found a new escape from anomie through individualistic empowerment, by which women grab hold of the social roles they desire to fill. Guruji altered the religious traditions already in place within Hinduism in order to follow the instructions given him by the Goddess, and in so doing he created a system within which women could become agents to act for themselves. The women of Devipuram are no longer defined by their roles of wife, mother, and daughter-in-law that weigh on them so heavily within a mechanical system, nor are they adopting the role of cogs in a machine that defines so much of organic society. Instead, they have discovered a group that allows them an alternative way to live, gives them opportunities to be leaders in private and in public, and tells them that they have worth as women, independent of the worth of their husbands. In empowering women, Devipuram has allowed Indian women to create new social identities for themselves, even while the majority of the country still marches to a patriarchal drum. As these women worship Devi, and learn of her, they learn a life-altering truth: “I am Devi, you are Devi, we are Devi.”

References

- ↑ Sri Amritananda Natha Saraswati (Guruji).

- ↑ "Asian Age, "Nothing shameful about nudity."". Retrieved 2007-09-08.

- 1 2 3 Devipuram History

- ↑ Devipuram Kumbha-Abhishekam Souvenir Magazine

- ↑ Devipuram Merus

- ↑ Sri Vidya Trust

- ↑ "Telugu People, "Devotion: Guru Pournami"". Retrieved 2007-09-05.

- ↑ "Devipuram to get a spiritual resort," The Hindu, July 13, 2005.

- ↑ "SriVilla is a comfortable, hygienic, and a safe holiday home," , October 4, 2010.

- ↑ Website announcement, Devipuram, March 14, 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Devipuram. |