Dendrocnide moroides

| Dendrocnide moroides | |

|---|---|

| | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Eudicots |

| (unranked): | Rosids |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Urticaceae |

| Genus: | Dendrocnide |

| Species: | D. moroides |

| Binomial name | |

| Dendrocnide moroides (Wedd.) Chew | |

Dendrocnide moroides, also known as the stinging brush, mulberry-leaved stinger, gympie gympie, gympie, gympie stinger,[1] stinger, the suicide plant, or moonlighter, is common to rainforest areas in the north east of Australia.[2][3][4] It is best known for stinging hairs that cover the whole plant and deliver a potent neurotoxin when touched. It is the most toxic of the Australian species of stinging trees.[2][4] The fruit is edible if the stinging hairs that cover it are removed.[5]

D. moroides usually grows as a single-stemmed plant reaching 1–3 metres in height. It has large, heart-shaped leaves about 12–22 cm long and 11–18 cm wide, with finely toothed margins.

Ecology

The species is unique in the genus Dendrocnide in having monoecious inflorescences in which the few male flowers are surrounded by female flowers.[4] The flowers are small, and once pollinated, the stalk swells to form the fruit. Fruits are juicy, mulberry-like, and are bright pink to purple. Each fruit contains a single seed on the outside of the fruit.[6]

The species is an early coloniser in rainforest gaps; seeds germinate in full sunlight[7] after soil disturbance. Although relatively common in Queensland, the species is uncommon in its southern-most range, and is listed as an endangered species in New South Wales.[3][8]

The giant stinging tree and the shining-leaved stinging tree are other large trees in the nettle family occurring in Australia.

Toxicity

Contact with the leaves or twigs causes the hollow, silica-tipped hairs to penetrate the skin. The hairs cause an extremely painful stinging sensation that can last for days, weeks, or months, and the injured area becomes covered with small, red spots joining together to form a red, swollen welt. The sting is infamously agonizing. Ernie Rider, who was slapped in the face and torso with the foliage in 1963, said "For two or three days the pain was almost unbearable; I couldn’t work or sleep, then it was pretty bad pain for another fortnight or so. The stinging persisted for two years and recurred every time I had a cold shower. ... There's nothing to rival it; it's ten times worse than anything else."[9] However, the sting does not stop several small marsupial species, including the red-legged pademelon, insects and birds from eating the leaves.[6]

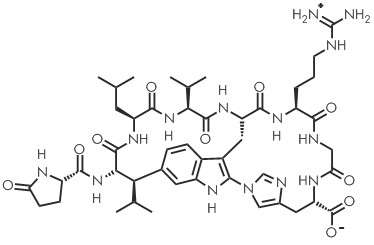

Moroidin, a bicyclic octapeptide containing an unusual C-N linkage between tryptophan and histidine, was first isolated from the leaves and stalks of Dendrocnide moroides, and subsequently shown to be the principal compound responsible for the long duration of the stings.[10]

There has been anecdotal evidence of some plants having no sting, but still possessing the hairs, suggesting a chemical change to the toxin.[11]

Treatment

The recommended treatment for skin exposed to the hairs is to apply diluted hydrochloric acid (1:10) [12] and to remove the hairs with a hair removal strip. [13][14] If this is unavailable, a strip of adhesive tape and/or tweezers may be used. Care should be taken to remove the hairs intact, without breaking them, as broken hair tips, if they remain buried, will only increase the level of pain.

Cases

Research scientist Marina Hurley spent three years studying the stinging trees in the Atherton Tableland (Queensland), wearing protective clothing. Her initial symptoms lasted for hours and involved sneezing fits, watering eyes and a runny nose, but the allergy became more severe with repeated exposure. In one incident she had to be hospitalized. Her extreme itching and urticaria required steroid treatment.[9]

References

- ↑ "Dendrocnide moroides (Wedd.) Chew". Australian Plant Name Index (APNI), IBIS database. Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research, Australian Government. Retrieved 7 Nov 2013.

- 1 2 Hyland, B. P. M.; Whiffin, T.; Zich, F. A.; et al. (Dec 2010). "Factsheet – Dendrocnide moroides". Australian Tropical Rainforest Plants. Edition 6.1, online version [RFK 6.1]. Cairns, Australia: Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), through its Division of Plant Industry; the Centre for Australian National Biodiversity Research; the Australian Tropical Herbarium, James Cook University. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- 1 2 Harden, Gwen J. (2001). "Dendrocnide moroides (Wedd.) Chew – New South Wales Flora Online". PlantNET – The Plant Information Network System. 2.0. Sydney, Australia: The Royal Botanic Gardens and Domain Trust. Retrieved 26 Nov 2013.

- 1 2 3 Chew, Wee-Lek (1989). "Dendrocnide moroides (Wedd.) Chew". Flora of Australia: Volume 3: (online version). Flora of Australia series. CSIRO Publishing / Australian Biological Resources Study. p. 76; figs 12, 36; map 84. ISBN 978-0-644-08499-4. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ "IS IT EDIBLE? - An introduction to Australian Bush Tucker". ACS Distance Education. Archived from the original on March 15, 2014. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- 1 2 Hurley, M. (2000). "Growth dynamics and leaf quality of the stinging trees Dendrocnide moroides and Dendrocnide cordifolia (Family Urticaceae) in Australian tropical rainforest: implications for herbivores". Australian Journal of Botany. 48: 109–201. Retrieved 26 Nov 2013.

- ↑ If You Touch This Plant It Will Make You Vomit In Pure Agony

- ↑ "Gympie Stinger – profile". Threatened Species. New South Wales, Australia: Department of Environment and Heritage. Retrieved 26 Nov 2013.

- 1 2 "Once Stung, never Forgotten", Australian Geographic

- ↑ proseanet.org: Dendrocnide

- ↑ "Gympie-Gympie losing its sting?", Australian Geographic

- ↑ "Gympie-Gympie Factsheet", Australian Geographic

- ↑ "Stinging Trees", Karl S. Kruszelnicki, ABS Science, abc.net.au

- ↑ "Stinging Trees - and a NEW Treatment for stings", Cape Tribulation Tropical Research Station

Further reading

- Stewart, Amy (2009). Wicked Plants: The Weed that Killed Lincoln's Mother and Other Botanical Atrocities. Etchings by Briony Morrow-Cribbs. Illustrations by Jonathon Rosen. Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. ISBN 978-1-56512-683-1.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dendrocnide moroides. |

External links

- Dendrocnide at Department of Biology, Davidson College

- Being Stung by the Gympie Gympie Tree Is One of the Worst Kinds of Pain You Can Imagine (2015-01-23), Oddity Central