Demography of Liverpool

The demography of Liverpool is officially analysed by the Office for National Statistics. The City of Liverpool together with the Metropolitan Borough of Sefton, the Metropolitan Borough of Knowsley, the Metropolitan Borough of St Helens and the Metropolitan Borough of Wirral forms the metropolitan county of Merseyside. With a population of around 466,400, Liverpool is the largest settlement in the county, the largest in North West England, and the fourth largest in the United Kingdom.

Population change

As with other major British cities, Liverpool has a large and diverse population. In the 2011 UK Census the recorded population of Liverpool was 466,400,[1] a 5.5% increase on the figure of 435,500 recorded in the 2001 census.[2] Liverpool's population peaked in the 1930s with 846,101 recorded in the 1931 census.[3] Until the 2011 figures were released revealing a return to population growth, the city had experienced negative population growth every decade with at its peak over 100,000 people leaving the city between 1971 and 1981.[4] Between 2001 and 2006 it experienced the ninth largest percentage population loss of any UK unitary authority.[5]

In common with many cities, Liverpool's population is younger than that of England as a whole, with 42.3 per cent of its population under the age of 30, compared to an English average of 37.4 per cent.[6] Those of working age make up 65.1 per cent of the population.[6]

Urban and metropolitan area

The Liverpool Urban Area encompasses the city of Liverpool alongside Sefton, Knowsley, Haydock and St. Helens had a population of 816,216 in 2001, which ranks seventh out of all UK conurbations.[7] Merseyside had an estimated population of 1,347,900 in 2008 (the county of Merseyside includes the Liverpool Urban Area and the Birkenhead Urban Area, which lie to the east and west of the River Mersey respectively).[8] The Greater Manchester Urban Area, which straddles a border with the Liverpool Urban Area, had a population of 2,240,230 in 2001, making the more or less continuous corridor of settlements between Liverpool and Manchester one of Europe's largest urban areas.[9]

Ethnicity

| Liverpool | North West England | England | |

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 91.0% | 91.6% | 87.5% |

| White British | 86.3% | 88.4% | 82.8% |

| Other White | 4.7% | 3.2% | 4.7% |

| Mixed | 2.0% | 1.3% | 1.9% |

| Asian or Asian British | 3.0% | 4.7% | 6.0% |

| Indian | 1.5% | 1.6% | 2.7% |

| Pakistani | 0.7% | 2.1% | 1.9% |

| Bangladeshi | 0.3% | 0.6% | 0.7% |

| Other Asian | 0.5% | 0.4% | 0.7% |

| Black or Black British | 1.9% | 1.1% | 2.9% |

| Black Caribbean | 0.5% | 0.4% | 1.2% |

| Black African | 1.1% | 0.6% | 1.5% |

| Other Black | 0.3% | 0.1% | 0.2% |

| Chinese or other ethnic group | 2.1% | 1.1% | 1.6% |

| Chinese | 1.1% | 0.6% | 0.8% |

| Other ethnic group | 1.0% | 0.5% | 0.8% |

While more than 90 per cent of Liverpool's population is white, the city is one of the most important sites in the history of multiculturalism in the United Kingdom. Liverpool is home to Britain's oldest Black community, dating to at least the 1730s, and some Black Liverpudlians are able to trace their ancestors in the city back ten generations.[11] Early Black settlers in the city included seamen, the children of traders sent to be educated, and freed slaves, since slaves entering the country after 1722 were deemed free men.[12]

The city is also home to the oldest Chinese community in Europe; the first residents of the city's Chinatown arrived as seamen in the nineteenth century.[13] The gateway in Chinatown is also the largest gateway outside of China.

The city is also known historically for its large Irish and Welsh populations.[14] The Scouse accent is thought to have been influenced by the arrival of Irish and Welsh migrants to the city.[15] Today, up to 50 per cent of the local population is believed to have Irish ancestry. The Irish and Welsh influences on Liverpool have given its people cultural traits usually associated with the Celtic fringes of the British Isles.[16]

The vast majority of Liverpool's ethnic minorities live within the 'inner city' area, particularly in and around Toxteth. According to the 2001 census, 38 per cent of the population of Granby,[17] 37 per cent of Princes Park[18] and 27 per cent of Central Liverpool[19] were from ethnic groups other than White British.

Major ethnic and national groups

The largest and most significant non-English ethnic and national groups in Liverpool are listed in alphabetical order below.

Afro-Caribbeans

Traditionally, and even today, the Afro-Caribbean population of Liverpool has been largely outnumbered by Black Africans. In 2009, just under 5,000 Liverpudlians were of Afro-Caribbean origin (most of these actually being of mixed White and Black origins).[10] This is compared to the 6,900 plus individuals of full or partial Black African origin in the city.[10] The International Organization for Migration estimates that Liverpool is home to between 1,000 and 2,000 Jamaicans, with the vast majority of these residing in Toxteth and Granby.[20] Some Black Africans in Liverpool can trace their ancestry back to the city's links with the slave trade, whilst Afro-Caribbeans are a fairly recent and emerging ethnic group.[21] By far the largest wave of Afro-Caribbean immigrants to the UK occurred in the 1940s and 1950s, when the British government encouraged people to come over and help contribute to the economy by taking up empty job vacancies. However, this only really came into effect in London.[21] During this period, Liverpool was rife with unemployment (twice the national average, in fact), and although Liverpool was and still is considered to be one of the country's most important cities, the lack of jobs on offer at the time deterred Afro-Caribbeans from wanting to move to the city.[21] Despite being a relatively small community, Afro-Caribbeans have made a significant contribution to the history and culture of the city. There are numerous Afro-Caribbean-owned businesses and community centres in and around Toxteth and the Smithdown Road area. In 1981, Afro-Caribbeans in the city were brought into the spotlight as a result of the Toxteth riots, which lasted four days and 150 buildings were eventually burnt down. The riots were a result of growing tensions between the police and local youths mainly from the local Afro-Caribbean community.[22]

Chinese

Liverpool is home to the oldest Chinese community in Europe.[13] According to 2009 estimates, 1.1 per cent of Liverpool's population are of Chinese ethnicity (some 5,000 people).[23] Despite this, the IOM has estimated that the true number of Chinese people in Liverpool could range between 25,000 and 35,000.[24] The first presence of Chinese people in Liverpool dated back to the early 19th century, with the main influx arriving at the end of the 19th century. This was in part due to the Alfred Holt and Company establishing the first commercial shipping line to focus on the then China trade. From the 1890s onwards, small numbers of Chinese began to set up businesses catering to the Chinese sailors working on Holt's lines and others. Some of these men married working class British women, resulting in a number of British-born Eurasian Chinese being born during World War II in Liverpool.[25] Although the Chinese population in Liverpool is much smaller than it was mid-20th century (due to many moving to Manchester and Birmingham for economic reasons), the city's Chinatown district has spread significantly since its first establishment, now taking up much of Berry Street. The 2001 census showed 1,542 Liverpudlians were born in the People's Republic of China and 1,228 in Hong Kong.[26] Liverpool has been twinned with China's largest city, Shanghai since 1999.[27]

Ghanaians

There is a strong presence of Ghanaians in Liverpool, with an estimated 9,000 individuals originating in the African nation living in the city.[28] Liverpool is a stronghold for overseas Ghanaian students; significant numbers study at the city's three universities, particularly Hope University. Hope works alongside the Ghanaian High Commission and has set up the 'High Value Scholarship for Ghana', which alongside the university's other scholarships has helped draw a large number of potential students from the African nation.[29]

Greeks

The Liverpool Greek community dates back over 180 years, and a group named the Liverpool Greek Society was established in 1996.[30] The first large wave of Greeks to the city occurred in 1821 after massacres of Greeks by Turkish invaders on the island of Chios. Significant numbers also came to work for the Ralli brothers, who recruited 40,000 Greeks in cities worldwide including New York City, Geneva and Liverpool.[30] The Greek Orthodox Church of St Nicholas in Toxteth was built in 1870 and serves the local Greek community. There are estimated to be 2,500 Greek Cypriots in the Merseyside area,[31] whilst 3,000 Greeks are estimated to live to the west of the River Mersey in the Wirral area, Chester and North Wales.[32]

Irish

Following the start of the Great Irish Famine, two million Irish people migrated to Liverpool in the space of one decade, many of them subsequently departing for the United States.[33] By 1851, more than 20 per cent of the population of Liverpool was Irish.[34] At the 2001 Census, 0.75 per cent of the population were born in the Republic of Ireland, while 0.54 per cent were born in Northern Ireland,[35] but up to 50 per cent of Liverpudlians are thought to have Irish ancestry.

Italians

Significant numbers of Italians first arrived in Liverpool in the 19th century. The main reason for Italians coming to the city was to embark on a journey from the port of Liverpool to the 'New World' in hope of a better life than in their native Italy.[36] Despite this many failed to complete the journey and actually remained in Liverpool, the largest numbers settling on and around Scotland Road, which soon became nicknamed 'Little Italy'.[36] Currently, some 3,000 Italians reside in Liverpool, although little over 200 were actually born in Italy.[37][38] There is an Italian Consulate located on the west side of the Mersey in Birkenhead adjacent to the Queensway Tunnel.[39]

Latin Americans

Liverpool and the surrounding urban area is home to UK's largest Latin American community outside London.[40][41] Although significant migration from Latin America to the United Kingdom only began in the 1970s, at a time of much political turmoil and civil unrest in Latin America, Liverpool's Latin American community has seen a large increase in size during the mid-2000s.[40] The majority of these people originate from Bolivia, Colombia, Brazil and Peru.[40] Liverpool City Council and other local services offer information and help in Spanish and Portuguese due to the city's large Latin American population.[42] The University of Liverpool is one of the few educational facilities in the country that teaches Latin American studies.[43] Amongst the most famous Latin Americans in Liverpool are the numerous expatriate footballers who play for the city's professional football clubs. Liverpool F.C.'s current first team includes two Brazilians and one Argentine.[44] Liverpool has friendship links with Havana, Cuba, La Plata, Argentina and Valparaiso, Chile.[27] Brazilica Festival is the UK's largest celebration of Brazilian culture and has been held annually in Liverpool since 2008.[45]

Malaysians

The IOM has stated that around 9,000 Malaysians live in the city which makes it one of the largest such communities in the country.[46] They are the second largest East Asian group in Liverpool. There are also an estimated 1,500 Vietnamese residing in the city.[47]

Somalis

Somalis number in the thousands in Liverpool, and are one of the city's longest established ethnic minority groups. According to the 2001 census, 678 Somali-born individuals were living in Liverpool,[48] but unofficial estimates place the figure between 4,000–9,000 inhabitants.[49][50] While many Somalis arrived in Liverpool seeking asylum after the outbreak of the Somali Civil War in 1991, there has been a presence of Somalis in the city since the 19th century, when many came to Liverpool to work for the British Navy,[50] often by way of the former British Somaliland protectorate.[50] Today, Liverpool City Council and local services offer information and help in the Somali language (this is alongside information in English and 15 other common languages in Liverpool).[42] The majority of Liverpool's Somali community reside in Toxteth, where there are numerous Somali-run businesses and community groups. In 2004, a local social worker, Mohamed "Jimmy" Ali, became the UK's first Somali councillor, although he has since lost his seat.[51]

South Asians

Like most British cities, Liverpool has a strong presence of South Asians. 2007 estimates put the number of people of Indian origin in the city at 6,700, Pakistanis at 3,200, Bangladeshis at 1,100. Some 2,000 people belonged to other South Asian groups whilst a further 2,000 individuals were of mixed South Asian and European origin.[10] Bengali and Urdu are amongst the most common foreign languages spoken in Liverpool.[42] The South Asian population of Liverpool is one of the city's fastest growing ethnic groups; in 2001 some 5,000 South Asians were residing in the city (1.1 per cent of the local population). Over the next eight years, the community more than doubled in size to 13,000 (3.0 per cent of the local population, which is actually much lower than England's average of 6.0 per cent).[10] The common belief that Liverpool doesn't have a long established Indian community like other British cities is in fact false. The Indian presence in Liverpool (although small in comparison to even nearby Preston) dates back to 1860s although these people only tended to be sailors and tradesmen.[52] However, around 1910 a group of Indian males from the Punjab region of India moved to Liverpool and established the city's first fixed community. During the World War I, many more came to Liverpool to look for work while numerous more came to the city after India was granted independence in 1947.[52] Two other significant waves of Indians to the city occurred when India was split into two separate countries (the other now known as Pakistan), the mass exodus of Indians from Kenya in the 1970s further added to Liverpool's long established South Asian community.[53] Historically, the first place Indians and fellow South Asians looked for work were the docks of Liverpool. It was a hard living with little pay and the fact that they spoke little to no English made it even harder.[52] They were proud people and working in oppressive conditions for people who were considered 'higher up', leading to many ending their jobs at the docks and seeking work elsewhere.[52] Eventually, large numbers of Indians in Liverpool set up their own businesses. Many began to work for themselves as street peddlers, entertainers and fortune tellers. The hours were long, but being their own boss appealed to many South Asians (a thought which is still maintained to this day).[52]

Welsh

In 1813, 10 per cent of Liverpool's population was Welsh, leading to the city becoming known as "the capital of North Wales".[14][54] 120,000 Welsh people migrated from Wales to Liverpool between 1851 and 1911.[55] At the 2001 Census, 1.17 per cent of the population were Welsh-born.[35]

There are a number of people who use the Welsh language as their first language in Liverpool.

Yemenis

Liverpool, like several other port cities (such as South Shields, Cardiff and Kingston upon Hull), has had a strong presence of Yemeni people for centuries.[56] After the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, an increase of trade between Britain and the Far East meant that more men had to be recruited to work in ports and on ships.[56] Aden in Yemen was the main refuelling point for the vast majority of ships sailing this route, which led to many locals taking up jobs in the field. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries many of these seamen moved ashore and set up home in the likes of Liverpool.[56] Yemenis (who are most likely Liverpool's largest Arab group) alongside Somalis are the two largest Muslim groups in the city and worship at Liverpool's three main mosques (including the Al-Rahma mosque).[57] It is unknown exactly how many Yemenis and people of Yemeni descent live in Liverpool, due to the fact that Yemeni ethnic/national origin couldn't be stated in the 2001 census. Despite this, the 'Arab' ethnic option was added to the 2011 UK Census.[58] Many Yemenis in the city are noted for running newsagents and corner shops, the number of which is estimated to be approximately 400 in 2008.[59]

Zimbabweans

People originating in Zimbabwe are another large Black African group in Liverpool; they are thought to number no fewer than 3,000.[60]

Country of birth

The 2001 Census showed that 92.79 per cent of Liverpool's residents were born in England, 1.17 per cent in Wales, 0.77 per cent in Scotland and 0.54 per cent in Northern Ireland. 0.75 per cent were born in the Republic of Ireland, 0.75 per cent elsewhere in the European Union and 3.27 per cent elsewhere in the world.[35] Foreign nations where more than 500 Liverpool residents in 2001 were born included: the Republic of Ireland, the People's Republic of China, Hong Kong, Germany, India, Somalia and Nigeria.[61]

Religion

According to the 2001 census, 79.5 per cent of the city's population followed Christianity, 1.4 per cent Islam, 0.6 per cent Judaism, 0.3 per cent Buddhism, 0.3 per cent Hindu and 0.1 per cent Sikhism. Just over 0.1 per cent of individuals belonged to another faith whilst 9.7 per cent claimed to be non-religious and 8.1 per cent did not state any religion.[62] The thousands of migrants and sailors passing through Liverpool resulted in a religious diversity that is still apparent today. This is reflected in the equally diverse collection of religious buildings, and two Christian cathedrals.

Christianity

The parish church of Liverpool is the Anglican Our Lady and St Nicholas, colloquially known as "the sailors church", which has existed near the waterfront since 1257. It regularly plays host to Catholic masses. Other notable churches include the Greek Orthodox Church of St Nicholas (built in the Neo-Byzantine architecture style), and the Gustav Adolf Church (the Swedish Seamen's Church, reminiscent of Nordic styles).

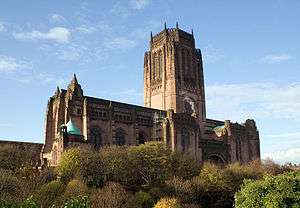

Liverpool's wealth as a port city enabled the construction of two enormous cathedrals, both dating from the 20th century. The Anglican Cathedral, which was designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott and plays host to the annual Liverpool Shakespeare Festival, has one of the longest naves, largest organs and heaviest and highest peals of bells in the world. The Roman Catholic Metropolitan Cathedral on Mount Pleasant next to Liverpool Science Park was initially planned to be even larger. Of Sir Edwin Lutyens' original design, only the crypt was completed. The cathedral was eventually built to a simpler design by Sir Frederick Gibberd; while this is on a smaller scale than Lutyens' original design, it still manages to incorporate the largest panel of stained glass in the world. The road running between the two cathedrals is called Hope Street, a coincidence which pleases believers. The cathedral is colloquially referred to as "Paddy's Wigwam" due to its shape.[63][64]

Judaism

Liverpool contains several synagogues, of which the Grade I listed Moorish Revival Princes Road Synagogue is architecturally the most notable. Princes Road is widely considered to be the most magnificent of Britain's Moorish Revival synagogues and one of the finest buildings in Liverpool.[65] Liverpool has a thriving Jewish community with a further two orthodox Synagogues, one in the Allerton district of the city and a second in the Childwall district of the city where a significant Jewish community reside. A third orthodox Synagogue in the Greenbank Park area of L17 has recently closed, and is a listed 1930s structure. There is also a Lubavitch Chabad House and a reform Synagogue. Liverpool has had a Jewish community since the mid-18th century. The current Jewish population of Liverpool is around 3,000.[66]

Islam

The city had one of the earliest mosques in Britain, founded in 1887 by William Abdullah Quilliam, a lawyer who had converted to Islam. This mosque, which was also the first in England, however no longer exists.[67] Plans have been ongoing to re-convert the building where the mosque once stood into a museum.[68] Currently there are three mosques in Liverpool: the largest and main one, Al-Rahma mosque, in the Toxteth area of the city and a mosque recently opened in the Mossley Hill district of the city. The third mosque was also recently opened in Toxteth and is on Granby Street. Multi-million pound plans to refurbish and restore the city's first mosque were revealed in January 2010.[69]

Hinduism

Liverpool also has an increasing Hindu community, with a Mandir on 253 Edge Lane; the Radha Krishna Hindu Temple from the Hindu Cultural Organisation based there. The current Hindu population in Liverpool is about 1147.

Sikhism

Liverpool also has the Guru Nanak Sikh Gurdwara in L15.

References

- ↑ "Resident Population Estimates Jun2001, All Persons". Office for National Statistics. 18 December 2007. Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- ↑ "Resident Population Estimates, All Persons". Office for National Statistics. 1 October 2009. Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- ↑ "Liverpool District: Total Population". A Vision of Britain through Time. University of Portsmouth. Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- ↑ "Liverpool District: Population Change". University of Portsmouth. Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- ↑ "UK population grows to 60,587,000 in mid-2006" (PDF). Office for National Statistics. 22 August 2007. p. 9. Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- 1 2 "Neighbourhood Statistics: Resident Population Estimates by Broad Age Band". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- ↑ "Key Statistics for urban areas in the North – Contents, Introduction, Tables KS01 – KS08" (PDF). Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

- ↑ "Table 10: Local Authority components of change 2008". Archived from the original on 18 November 2010.

- ↑ "Key Statistics for urban areas in England and Wales". Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 15 February 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Neighbourhood Statistics: Resident Population Estimates by Ethnic Group (Percentages)". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 20 May 2011.

- ↑ Costello, Ray (2001). Black Liverpool: The Early History of Britain's Oldest Black Community 1730–1918. Liverpool: Picton Press. ISBN 1-873245-07-6.

- ↑ McIntyre-Brown, Arabella; Woodland, Guy (2001). Liverpool: The First 1,000 Years. Liverpool: Garlic Press. p. 57. ISBN 1-904099-00-9.

- 1 2 "Culture and Ethnicity Differences in Liverpool – Chinese Community". Chambré Hardman Trust. Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- 1 2 "Culture and Ethnicity Differences in Liverpool – European Communities". Chambré Hardman Trust. Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- ↑ Coslett, Paul (11 January 2005). "The origins of Scouse". BBC Liverpool. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- ↑ "Why city is the real capital of Ireland...". Liverpool Echo. 17 March 2003. Archived from the original on 29 September 2012.

- ↑ "Area: Granby (Ward)". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ↑ "Area: Princes Park (Ward)". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ↑ "Area: Central (Ward)". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ↑ "Jamaica Mapping Exercise" (PDF). International Organization for Migration. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Deconstructing the Liverpool black identity". iamcolourful.com. Retrieved 2 February 2010.

- ↑ Vulliamy, Ed (3 July 2011). "Toxteth revisited, 30 years after the riots". The Guardian. London.

- ↑ "Area: Liverpool (Local Authority)". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ↑ "China Mapping Exercise" (PDF). International Organization for Migration. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ↑ "Liverpool and its Chinese Seaman". halfandhalf.org.uk. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ↑ "Area: Liverpool (Local Authority)". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- 1 2 "Twinning". Liverpool City Council. Archived from the original on 18 December 2010.

- ↑ "Ghana Mapping Exercise" (PDF). International Organization for Migration. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ↑ "New scholarship for Ghanaian students available at Liverpool Hope". Postgrad.com. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- 1 2 "History". Liverpool Greek Society. Retrieved 2 February 2010.

- ↑ Bartlett, David (7 August 2007). "City Greek community to get its own centre at last". Liverpool Daily Post. Archived from the original on 26 September 2012. Retrieved 2 February 2010.

- ↑ "Liverpool Greek Society needs £1m to build school and community centre". Wirral News. Retrieved 2 February 2010.

- ↑ "Coast Walk: Stage 5 – Steam Packet Company". BBC. Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- ↑ "Leaving from Liverpool". National Museums Liverpool. Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Neighbourhood Statistics: Country of Birth". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- 1 2 "Bringing Italy to Liverpool". Liverpool Echo. 16 June 2007. Retrieved 30 January 2010.

- ↑ "Italian Fans to turn out in force to cheer Liverpool". Liverpool Daily Post.

- ↑ "Area: Liverpool (Local Authority)". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ↑ "Italian Consulate". Yahoo!. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Liverpool's Latin quarter – just around the corner". Liverpool.com. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ↑ Key, Phil (21 December 2007). "Keep the culture real, keep it Latin". Liverpool Daily Post. Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Translation". Liverpool.gov.uk. Retrieved 1 February 2010.

- ↑ "University course search". Ucas. Retrieved 1 February 2010.

- ↑ "First team". Liverpool F.C. Retrieved 1 February 2010.

- ↑ "Brazilica samba festival in Liverpool this weekend". Click Liverpool. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- ↑ "Malaysia Mapping Exercise" (PDF). International Organization for Migration. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ↑ "Vietnam Mapping Exercise" (PDF). International Organization for Migration. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ↑ "Area: Liverpool (Local Authority)". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ↑ http://www.liverpoolpct.nhs.uk/Library/Impact/IA0073.doc

- 1 2 3 "Integration of the Somali Community into Europe". Federation of Adult Education Associations. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- ↑ Casciani, Dominic (30 May 2006). "Somalis' struggle in the UK". BBC News. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Vilayat – Coming to Liverpool". liverpoolmuseums.org. Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 3 February 2010.

- ↑ "Culture and Ethnicity Differences in Liverpool – Indian Community". mersey-gateway.org. Archived from the original on 25 May 2011. Retrieved 3 February 2010.

- ↑ Morphy, Jim (22 October 2013). "The Welsh of Liverpool". Wales Art Review. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ↑ http://new.wales.gov.uk/news/archivepress/officefirstminspress/firstminpress2004/706222/?lang=en

- 1 2 3 "Islam and Britain". BBC. Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- ↑ "Islamic Cultural Centre and Al-Rahma Mosque". muslimsinbritain.org. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ↑ "2011 Census Questions Published". BBC News. 21 October 2009. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ↑ "Tribute to newsagent gunned down in Huyton". Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- ↑ "Zimbabwe Mapping Exercise" (PDF). International Organization for Migration. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ↑ "Area: Liverpool (Local Authority)". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ↑ "Area: Liverpool (Local Authority)". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ↑ Clarke, Wayne. "Cathedral celebrates anniversary". BBC. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ↑ The term may have its origins in religious and racial sectarianism, which, while now largely disappeared, was once notoriously virulent in Liverpool.

- ↑ Sharples, Joseph (2004). Pevsner Architectural guide to Liverpool. Yale University Press. p. 249.

- ↑ Miller, Colin (25 November 2006). "Liverpool's Jewish Heritage and Urban Regeneration". Archived from the original on 6 February 2007. Retrieved 13 May 2007.

- ↑ Sardais, Louise. "Architectural Heritage – The 'little mosque'". BBC. Retrieved 24 January 2009.

- ↑ Sardais, Louise. "Architectural Heritage – The 'little mosque'". BBC. Retrieved 24 January 2009.

- ↑ Bartlett, David (15 January 2010). "Liverpool City Council's plans to restore Britain's first mosque". Liverpool Daily Post. Archived from the original on 30 September 2012.