DEFCON

The DEFense readiness CONdition (DEFCON) is an alert state used by the United States Armed Forces.[1]

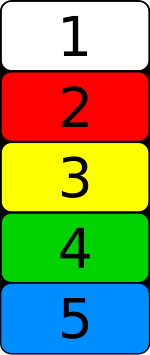

The DEFCON system was developed by the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) and unified and specified combatant commands.[2] It prescribes five graduated levels of readiness (or states of alert) for the U.S. military. It increases in severity from DEFCON 5 (least severe) to DEFCON 1 (most severe) to match varying military situations.[1]

DEFCONs are a subsystem of a series of Alert Conditions, or LERTCONs, which also include Emergency Conditions (EMERGCONs).[3]

Operations

The DEFCON level is controlled primarily by the U.S. President and the U.S. Secretary of Defense through the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Combatant Commanders, and each DEFCON level defines specific security, activation and response scenarios for the troops in question.

Different branches of the U.S. Armed Forces (i.e. U.S. Army, U.S. Navy, U.S. Air Force, U.S. Marine Corps, U.S. Coast Guard) and different bases or command groups can be activated at different defense conditions. In general, there is no single DEFCON status for the world or country and it may be set to only include specific geographical areas. According to Air & Space/Smithsonian, as of 2014, the worldwide DEFCON level has never risen higher than DEFCON 3. The DEFCON 2 levels in the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis and 1991 Gulf War were not worldwide.[4]

DEFCONs should not be confused with similar systems used by the U.S. military, such as Force Protection Conditions (FPCONS), Readiness Conditions (REDCONS), Information Operations Condition (INFOCON) and its future replacement Cyber Operations Condition (CYBERCON),[5] and Watch Conditions (WATCHCONS), or the former Homeland Security Advisory System used by the United States Department of Homeland Security.

Levels

Defense readiness conditions vary between many commands and have changed over time,[2] and the United States Department of Defense uses exercise terms when referring to the DEFCONs.[6] This is to preclude the possibility of confusing exercise commands with actual operational commands.[6] On 12 January 1966, NORAD "proposed the adoption of the readiness conditions of the JCS system", and information about the levels was declassified in 2006:[7]

| Readiness condition | Exercise term | Description | Readiness |

|---|---|---|---|

| DEFCON 1 | COCKED PISTOL | Nuclear war is imminent | Maximum readiness |

| DEFCON 2 | FAST PACE | Next step to nuclear war | Armed Forces ready to deploy and engage in less than 6 hours |

| DEFCON 3 | ROUND HOUSE | Increase in force readiness above that required for normal readiness | Air Force ready to mobilize in 15 minutes |

| DEFCON 4 | DOUBLE TAKE | Increased intelligence watch and strengthened security measures | Above normal readiness |

| DEFCON 5 | FADE OUT | Lowest state of readiness | Normal readiness |

History

After NORAD was created, the command used different readiness levels (Normal, Increased, Maximum) subdivided into eight conditions, e.g., the "Maximum Readiness" level had two conditions "Air Defense Readiness" and "Air Defense Emergency".[7] In October 1959, the JCS Chairman informed NORAD "that Canada and the U. S. had signed an agreement on increasing the operational readiness of NORAD forces during periods of international tension."[7] After the agreement became effective on 2 October 1959,[7] the JCS defined a system with DEFCONs in November 1959 for the military commands.[2] The initial DEFCON system had "Alpha" and "Bravo" conditions (under DEFCON 3) and Charlie/Delta under DEFCON 4, plus an "Emergency" level higher than DEFCON 1 with two conditions: "Defense Emergency" and the highest, "Air Defense Emergency" ("Hot Box" and "Big Noise" for exercises).[7]

DEFCON 2

Cuban Missile Crisis

During the Cuban Missile Crisis on October 22, 1962, the U.S. Armed Forces (with the exception of United States Army Europe (USAREUR)) were ordered to DEFCON 3. On October 24, Strategic Air Command (SAC) was ordered to DEFCON 2, while the rest of the U.S. Armed Forces remained at DEFCON 3. SAC remained at DEFCON 2 until November 15.[8]

Gulf War

On January 15, 1991, the Joint Chiefs of Staff declared DEFCON 2 in the opening phase of Operation Desert Storm during the Gulf War.[9]

DEFCON 3

Yom Kippur War

On October 6, 1973, Egypt and Syria launched a joint attack on Israel resulting in the Yom Kippur War. The U.S. became concerned that the Soviet Union might intervene, and on October 25, U.S. forces, including Strategic Air Command, Continental Air Defense Command, European Command and the Sixth Fleet, were placed at DEFCON 3.

According to documents declassified in 2016, the move to DEFCON 3 was motivated by Central Intelligence Agency reports indicating that the Soviet Union had sent a ship to Egypt carrying nuclear weapons along with two other amphibious vessels.[10] Soviet troops never landed, though the ship supposedly transporting nuclear weapons did arrive in Egypt. Further details are unavailable and may remain classified.

Over the following days, the various forces reverted to normal status with the Sixth Fleet standing down on November 17.[11]

Operation Paul Bunyan

Following the axe murder incident at Panmunjom on August 18, 1976, readiness levels for American forces in South Korea were increased to DEFCON 3, where they remained throughout Operation Paul Bunyan which followed thereafter.[12]

September 11 attacks

During the attacks of September 11, 2001, the U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld ordered the increased DEFCON level to 3, and also a stand-by for a possible increase to DEFCON 2.[13]

In other media

- DEFCON was used significantly in the films WarGames, Thirteen Days, Watchmen, Independence Day, The Sum of All Fears, By Dawn's Early Light, Crimson Tide and Canadian Bacon.

- The television series Deutschland 83 depicts the events which occurred in 1983 when the level was raised to a simulated DEFCON 1 during NATO exercise Able Archer 83. In the story line, briefing papers released under the Freedom of Information Act reveal that Operation Able Archer, a major war games exercise conducted in November 1983 by the US and its NATO allies, was so realistic it made the Russians believe that a nuclear strike on its territory was a real possibility.[14]

- The 2006 real-time strategy video game DEFCON.

See also

- Doomsday Clock

- Homeland Security Advisory System

- HURCON – Hurricane Condition threat rating (military-developed scale)

- National Command Authority

- National Military Command Center

- UK Threat Levels – Similar British system used for terrorism threats

References

- 1 2 "Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms" (PDF). 12 April 2001 (As Amended Through 19 August 2009). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 November 2009. Retrieved 1 February 2014. (DEFCON is not mentioned in the 2010 and newer document)

- 1 2 3 Sagan, Scott D. (Summer 1985). "Nuclear Alerts and Crisis Management" (pdf). International Security. 9 (4): 99–139. doi:10.2307/2538543 – via Project Muse.

- ↑ "Emergency Action Plan (SEAP)" (PDF). United States Army Corps of Engineers Savannah District (CESAS) Plan 500-1-12. 1 August 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-02-03.

- ↑ Chiles, James R. (March 2014). "Go To DEFCON 3". Air & Space/Smithsonian.

- ↑ Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Instruction 6510.01F

- 1 2 "Emergency Action Procedures of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Volume I - General" (PDF). US DoD FOIA Reading Room. April 24, 1981. pp. 4–7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 NORAD/CONAD Historical Summary: July -December 1959 (PDF) (Report). Retrieved 2013-09-25.

- ↑ "DEFCON DEFense CONdition". fas.org.

- ↑ Meyers, Harold P. (1992) "Nighthawks over Iraq, a study a study of the F117-A stealth fighter in operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm." U.S. Air Force Office of History.

- ↑ Naftali, Tim. "CIA reveals its secret briefings to Presidents Nixon and Ford". CNN. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- ↑ Goldman, Jan (16 June 2011). Words of Intelligence: An Intelligence Professional's Lexicon for Domestic and Foreign Threats. Scarecrow Press. pp. 93–. ISBN 978-0-8108-7476-3.

- ↑ Probst, Reed R. (16 May 1977). "Negotiating With the North Koreans: The U.S. Experience at Panmunjom" (PDF). Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania: U.S. Army War College. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 24, 2005. Retrieved 17 December 2009.

- ↑ "Complete 911 Timeline: Donald Rumsfeld's Actions on 9/11". www.historycommons.org. Retrieved 2016-08-02.

- ↑ Doward, Jamie (November 2, 2013). "How a NATO War Game Took the World to Brink of Nuclear Disaster". The Observer. London. Retrieved September 23, 2016.

External links

-

Media related to DEFCON at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to DEFCON at Wikimedia Commons