Decretum Gelasianum

The Decretum Gelasianum or the Gelasian Decree is so named because it was traditionally thought to be a Decretal of the prolific Pope Gelasius I, bishop of Rome 492–496. It is said that the work was derived from a five-chapter text written by an anonymous scholar between 519 and 553, the second chapter of which is a list of books of Scripture presented as having been made Canonical by a Council of Rome under Pope Damasus I, bishop of Rome 366-383. The so-called Damasine List, while not actually canonical,[1] represents the same canon as shown in the Council of Carthage Canon 24, 419 AD.[2]

Content

The Decretum has five parts. Parts 1, 3, and 4 are not relevant to the canon. The second part is a canon catalogue. The Deuterocanonical Books are accepted by the catalogue, and are still found in the Roman Catholic Bible, though not in the Protestant canon. The canon catalogue gives 27 books of the New Testament. In the list of gospels, the order is given as Matthew, Mark, Luke, John. Fourteen epistles are credited to Paul including Philemon and Hebrews. Of the General Epistles seven are accepted: two of Peter, one of James, one of the apostle John, two of "the other John the elder" (presbyter), and one of "Judas the Zealot".[3]

The fifth part is a catalogue of the "apocryphal books" and other writings which are to be rejected, presented as adjudged apocryphal "by Pope Gelasius and seventy most erudite bishops." Though the ascription is generally agreed to be apocryphal itself, except among the most traditional of apologists, it perhaps makes allusion to the seventy translators of the Septuagint and the seventy apostles sent out in Luke. This list de libris recipiendis et non recipiendis ("of books to be admitted and not to be admitted"), probably originating in the 6th century, represents a tradition that can be traced back to Pope Damasus I and reflects Roman practice in the development of the Biblical canon. These apocrypha are not the same as the Deuterocanonical Books, but include the Acts of Andrew and other spurious works.[3]

Textual history

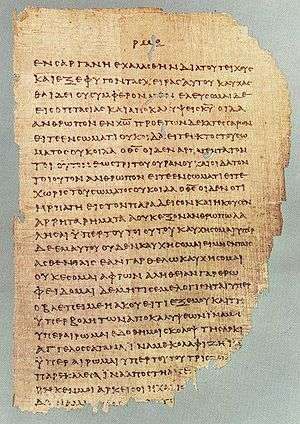

The complete text is preserved in the mid-eighth-century Ragyndrudis Codex, fols. 57r-61v,[4] which is the earliest manuscript copy containing the complete text. The earliest manuscript copy was produced c. 700, Brussels 9850-2.[5]

Versions of the work appear in multiple surviving manuscripts, some of which are titled as a Decretal of Pope Gelasius, others as a work of a Roman Council under the earlier Pope Damasus. However, all versions show signs of being derived from the full five-chapter text, which contains a quotation from Augustine, writing about 416 after Damasus, revealing one of the evidence why this document is considered as "the production of an anonymous scholar of the sixth century".[1]

References

- 1 2 Burkitt.

- ↑ http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/3816.htm

- 1 2 Decretum Gelasianum.

- ↑ Stork, Hans-Walter (1994). "Der Codex Ragyundrudis im Domschatz zu Fulda (Codex Bonifatianus II)". In Lutz E. von Padberg Hans-Walter Stork. Der Ragyndrudis-Codes des Hl. Bonifatius (in German). Paderborn, Fulda: Bonifatius, Parzeller. pp. 77–134. ISBN 3870888113.

- ↑ McKitterick, Rosamond (1989-06-29). The Carolingians and the Written Word. Cambridge UP. p. 202. ISBN 9780521315654.

External links

- The Development of the Canon": Decretum Gelasianum gives the full list, including the apocrypha "which are to be avoided by Catholics."

- Decretum Gelasianum: at The Latin Library.

- Decretum Gelasianum: in English.

- Review of Ernst von Dobschütz, Das Decretum Gelasianum de libris recipiendis et non recipiendis in kritischem Text Leipzig, 1912: F. C. Burkitt in Journal of Theological Studies 14 (1913) pp. 469–471.