Deadweight loss

In economics, a deadweight loss (also known as excess burden or allocative inefficiency) is a loss of economic efficiency that can occur when equilibrium for a good or service is not achieved or is not achievable. Causes of deadweight loss can include monopoly pricing (in the case of artificial scarcity), externalities, taxes or subsidies, and binding price ceilings or floors (including minimum wages). The term deadweight loss may also be referred to as the "excess burden" of monopoly or taxation.

Examples

For example, consider a market for nails where the cost of each nail is 10 cents and the demand will decrease linearly from a high demand for free nails to zero demand for nails at $1.10. In a perfectly competitive market, producers would have to charge a price of 10 cents and every customer whose marginal benefit exceeds 10 cents would have a nail. However, if there is one producer who has a monopoly on the product, then they will charge whatever price will yield the greatest profit. For this market, the producer would charge 60 cents and thus exclude every customer who had less than 60 cents of marginal benefit. The deadweight loss is then the economic benefit foregone by these customers due to the monopoly pricing.

Conversely, deadweight loss can also come from consumers buying a product even if it costs more than it benefits them. To describe this, let's use the same nail market, but instead it will be perfectly competitive, with the government giving a 3 cent subsidy to every nail produced. This 3 cent subsidy will push the market price of each nail down to 7 cents. Some consumers then buy nails even though the benefit to them is less than the real cost of 10 cents. This unneeded expense then creates the deadweight loss: resources are not being used efficiently.

If the price of a glass of wine is $3.00 and the price of a glass of beer is $3.00, a consumer might prefer to drink wine. If the government decides to levy a wine tax of $3.00 per glass, the consumer might prefer to drink beer. The excess burden of taxation is the loss of utility to the consumer for drinking beer instead of wine, since everything else remains unchanged.

Harberger's triangle

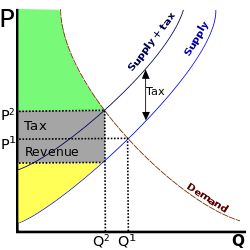

Harberger's triangle, generally attributed to Arnold Harberger, refers to the deadweight loss (as measured on a supply and demand graph) associated with government intervention in a perfect market. This can happen through price floors, caps, taxes, tariffs, or quotas. It also refers to the dead weight loss created by a government's failure to intervene in a market with externalities.[1]

The area represented by the triangle comes from the intersection of the supply and demand curves being cut short so that consumer surplus and producer surplus are also cut short. The loss of such surplus, not recouped by e.g. tax revenues, is the dead weight loss.

Some economists like James Tobin have argued that these triangles do not have a huge impact on the economy, whereas others (for example Martin Feldstein) maintain that they can seriously affect long term economic trends by pivoting the trend downwards, thus causing a magnification of losses in the long run.

Hicks vs. Marshall

An important distinction should be made between Hicksian (per John Hicks) and Marshallian (per Alfred Marshall) deadweight loss. The latter is related to the concept of consumer surplus, such that it can be shown that the Marshallian deadweight loss is zero where demand is perfectly elastic or supply is perfectly inelastic. However, Hicks analyzed the situation through indifference curves and noted that when the Marshallian Demand Curve exhibits perfect inelasticity, the policy or economic situation which caused a distortion in relative prices will have a substitution effect and that this substitution effect is a deadweight loss.

In modern economic literature, the most common measure of a taxpayer’s loss from a distortionary tax, such as a tax on bicycles, is the equivalent variation, which is the maximum amount that a taxpayer would be willing to forgo in a lump sum to avoid the distortionary tax. The deadweight loss can then be interpreted as the difference between the equivalent variation and the revenue raised by the tax. This difference is attributable to the behavioural changes induced by a distortionary tax that are measured by a substitution effect. However, this is not the only interpretation and Lind & Granqvist (2010) point out that Pigou did not use a lump sum tax as the point of reference when discussing deadweight loss (excess burden).

A comparable measure of loss is the compensating variation, which depends on Hicksian demand instead of Marshallian demand. In the context of a distortionary tax, the compensating variation is the minimum lump sum transfer that makes an individual indifferent between the lump sum transfer with tax and no lump sum transfer with no tax (the original situation). The deadweight loss can then be interpreted as the minimum lump sum.

See also

References

- ↑ "Negative Externality". Retrieved February 11, 2012.

Further reading

- Case, Karl E. & Fair, Ray C. (1999). Principles of Economics (5th ed.). Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-961905-4.

- Hines, James R., Jr. (1999), "Three sides of Harberger Triangles" (PDF), Journal of Economic Perspectives, 13 (2): 167–188, doi:10.1257/jep.13.2.167.

- Lind, H. & R. Granqvist (2010) A Note on the Concept of Excess Burden. Economic Analysis and Policy 40:63-73.