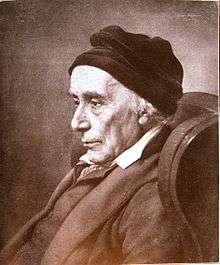

David Friedländer

David Friedländer (sometimes spelled Friedlander; 16 December 1750, Königsberg – 25 December 1834, Berlin) was a German Jewish banker, writer and communal leader.

Life

Friedländer settled in Berlin in 1771. As the son-in-law of the rich banker Daniel Itzig, and a friend, pupil, and subsequently intellectual successor of Moses Mendelssohn, he occupied a prominent position in both Jewish and non-Jewish circles of Berlin. His endeavors on behalf of the Jews and Judaism included the emancipation of the Jews of Berlin and the various reforms connected therewith. Frederick William II, on his accession, called a committee whose duty was to acquaint him with the grievances of the Jews, Friedländer and Itzig being chosen as general delegates. But the results of the conference were such that the Jews declared themselves unable to accept the reforms proposed, and not until after the French Revolution, with the edict of March 11, 1812, did the Jews then living on Prussian territory succeed in obtaining equal rights from Frederick William III.

Friedländer and his friends in the community of Berlin now turned their attention to the reform of worship in harmony with modern ideas and the changed social position of the Jews. The proposition in itself was perfectly justified, but the propositions of Friedländer, who had meanwhile been called (1813) to the conferences on the reorganization of the Jewish cult held in the Israelite Consistory of Westphalia (Royal Westphalian Consistory of the Israelites) at Cassel, were unacceptable to even the most radical members, as they tended to reduce Judaism to a mere colorless code of ethics.

Friedländer was more successful in his educational endeavors. He was one of the founders of a Jewish free school (1778), which he directed in association with his brother-in-law, Isaac Daniel Itzig. In this school, however, exclusively Jewish subjects were soon crowded out. Friedländer also wrote text-books, and was one of the first to translate the Hebrew prayer-book into German.

The "dry baptism" initiative

Friedländer was concerned with endeavors to facilitate for himself and other Jews entry into Christian circles. This disposition was evidenced in 1799 by his radical proposal to a leading Protestant provost in Berlin (Oberconsistorialrat) Wilhelm Teller. Friedländer's open letter (Sendschreiben) "in the name of some Jewish heads of families," stated that Jews would be ready to undergo "dry baptism": join the Lutheran Church on the basis of shared moral values if they were not required to believe in the divinity of Jesus and might evade certain Christian ceremonies. Much of the Open Letter was a polemic arguing that the Mosaic rituals were largely obsolete. So Judaism would thereby in return abandon many of its ceremonial features. The proposal "envisioned the establishment of a confederated unitarian church-synagogue."[1]

This "Sendschreiben an Seine Hochwürden Herrn Oberconsistorialrath und Probst Teller zu Berlin, von einigen Hausvätern Jüdischer Religion" (Berlin, 1799), elicited over a score of responses in pamphlets and the popular press, including ones from Abraham Teller and Friedrich Schleiermacher. Both rejected the notion of a sham conversion to Christianity as harmful to Christianity and the State, though, in line with Enlightenment values, neither precluded the idea of more civil rights for unconverted Jews. Jewish reaction to Friedländer's initiative was overwhelmingly hostile – it was called "a dishonorable act" and "desertion". Heinrich Graetz called him an "ape".[1]

In 1816, when the Prussian government decided to improve the situation of the Polish Jews, Franciszek Malczewski (Malziewsky), Bishop of Kujawy, consulted Friedländer. Friedländer gave the bishop a circumstantial account of the material and intellectual condition of the Jews, and indicated the means by which it might be ameliorated.

Literary career

Friedländer displayed great activity in literary work. Induced by Moses Mendelssohn, he began the translation into German of some parts of the Bible according to Mendelssohn's commentary. He translated Mendelssohn's "Sefer ha-Nefesh," Berlin, 1787, and "Ḳohelet," 1788. He wrote a Hebrew commentary to Abot and also translated it, Vienna, 1791; "Reden der Erbauung gebildeten Israeliten gewidmet," Berlin, 1815-17; "Moses Mendelssohn, von ihm und über ihn," ib. 1819; "Ueber die Verbesserung der Israeliten im Königreich Polen," ib. 1819, this being the answer which he wrote to the Bishop of Kujawia; "Beiträge zur Geschichte der Judenverfolgung im XIX. Jahrhundert durch Schriftsteller," ib. 1820.

Friedländer was assessor of the Royal College of Manufacture and Commerce of Berlin, and the first Jew to sit in the municipal council of that city. His wealth enabled him to be a patron of science and art, among those he encouraged being the brothers Alexander and Wilhelm von Humboldt.

Works

- Lesebuch für jüdische Kinder, Nachdr. d. Ausg. Berlin, Voss, 1779 / neu hrsg. u. mit Einl. u. Anh. vers. von Zohar Shavit, Frankfurt am Main : dipa-Verl., 1990. ISBN 3-7638-0132-4

- Übersetzung von Moses Mendelssohns Sefer ha-Nefesh. Berlin, 1787.

- Übersetzung von Moses Mendelssohns Ḳohelet. 1788.

- David Friedländers Schrift: Ueber die durch die neue Organisation der Judenschaften in den preußischen Staaten nothwendig gewordene Umbildung 1) ihres Gottesdienstes in den Synagogen, 2) ihrer Unterrichts-Anstalten und deren Lehrgegenstände und 3) ihres Erziehungwesens überhaupt : Ein Wort zu seiner Zeit. - Neudr. nebst Anh. der Ausgabe Berlin, in Comm. bei W. Dieterici, 1812. Berlin: Verl. Hausfreund, 1934. (Beiträge zur Geschichte der Jüdischen Gemeinde zu Berlin / Stern.

- Reden der Erbauung gebildeten Israeliten gewidmet. Berlin, 1815-17.

- Moses Mendelssohn, von ihm und über ihn. Berlin, 1819.

- Ueber die Verbesserung der Israeliten im Königreich Polen. Berlin, 1819.

- Beiträge zur Geschichte der Judenverfolgung im XIX. Jahrhundert durch Schriftsteller. Berlin, 1820.

See also

Notes

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "article name needed". Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company. by Isidore Singer and A. Kurrein.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "article name needed". Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company. by Isidore Singer and A. Kurrein.

- Lowenstein, Steven M.:The Jewishness of David Friedländer and the crisis of Berlin Jewry. Ramat-Gan, Israel: Bar-Ilan Univ., 1994. (Braun lectures in the history of the Jews in Prussia ; no. 3)

- Friedlander, David, Schleiermacher, Friedrich, and Teller, Wilhelm Abraham: A Debate on Jewish Emancipation and Christian Theology in Old Berlin. Crouter, Richard and Klassen, Julie (eds. and translators) Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Co., 2004.

- Bibliography of Jewish Encyclopedia article

- I. Ritter, Gesch. der Jüdischen Reformation, ii., David Friedländer;

- Ludwig Geiger, in Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie, vii.;

- Fuenn, Keneset Yisrael, pp. 250 et seq.;

- Rippner, in Gratz Jubelschrift, pp. 162 et seq.;

- Sulamith, viii. 109 et seq.;

- Der Jüdische Plutarch, ii. 56-60;

- Museum für die Israelitische Jugend, 1840;

- Zeitschrift für die Geschichte der Juden in Deutschland, i. 256-273.

External links

- Jewish Encyclopedia

- über die jüdische Freischule

- searching "David Friedländer" - Online-Gesamtkatalog Der Deutschen Bibliothek