Bristlebird

- "Dasyornis" redirects here. This was also used by Richard Lydekker for the prehistoric pseudotooth bird genus Dasornis in error.

| Dasyornis | |

|---|---|

| |

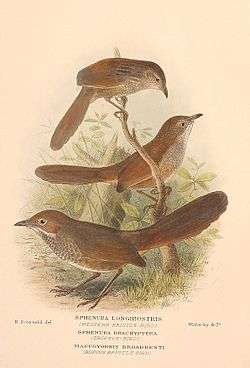

| Western, eastern and rufous bristlebirds | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Suborder: | Passeri |

| Superfamily: | Meliphagoidea |

| Family: | Dasyornithidae Sibley & Ahlquist, 1985 |

| Genus: | Dasyornis Vigors & Horsfield, 1827 |

| Species | |

|

Dasyornis brachypterus | |

The bristlebirds are a family, Dasyornithidae, of passerine bird. There are three species in one genus, Dasyornis. The family is endemic to Australia.[1] The genus Dasyornis was sometimes placed in the Acanthizidae or, as a subfamily, Dasyornithinae, along with the Acanthizinae and Pardalotinae, within an expanded Pardalotidae, before being elevated to full family level by Christidis & Boles (2008).[2][3]

Taxonomy and systematics

Taxa accepted or described by Schodde & Mason (1999)[4] include, with their estimated conservation status:

- Eastern bristlebird (Dasyornis brachypterus)

- D. brachypterus brachypterus - endangered

- D. brachypterus monoides - critically endangered

- Rufous bristlebird (Dasyornis broadbenti)

- D. broadbenti broadbenti - lower risk (least concern)

- D. broadbenti caryochrous - lower risk (near threatened)

- D. broadbenti litoralis (western rufous bristlebird) - extinct

- Western bristlebird (Dasyornis longirostris) - vulnerable

Description

Bristlebirds are long-tailed, sedentary, ground-frequenting birds. They vary in length from about 17 cm to 27 cm, with the eastern bristlebird the smallest, and the rufous bristlebird the largest, species. Their colouring is mainly grey with various shades of brown, ranging from olive-brown through chestnut and rufous, on the plumage of the upperparts. The grey plumage of the underparts or the mantle is marked by pale dappling or scalloping.[5] The common name of the family is derived from the presence of prominent rictal bristles.[2]

Distribution and habitat

Bristlebirds have restricted, and often reduced and disjunct, ranges along the coasts of south-western and south-eastern Australia where there is a Mediterranean climate and suitable habitat of coastal scrubs, heathlands and dense understorey vegetation in woodlands and forests.[2] The eastern bristlebird occurs in threatened, localised and disjunct populations down the eastern Australian coast from south-east Queensland through New South Wales to eastern Victoria; the rufous bristlebird in western Victoria and south-eastern South Australia, and formerly in south-western Western Australia; with the western bristlebird occurring in a small area of south-west Western Australia.[4]

Behaviour and ecology

Bristlebirds are generally shy diurnal birds that skulk in dense vegetation.[1] They preferentially run to avoid danger, but are capable of flying short distances. They generally occur in pairs, but their social structure has not been studied closely. They are more usually heard than seen, although it is usually the male that sings. The song is loud, melodic and can carry for some distances. The song is thought to be territorial in nature and is often made from on top of a log or shrub to better carry in the air.

Most of the food is found by foraging on the ground. Birds forage in pairs, making small contact calls to keep in touch, and constantly flicking their tails whilst moving. The major part of the diet is composed of insects and seeds. Spiders and worms are also taken, and birds have been observed drinking nectar as well.

The breeding behaviour of bristlebirds is poorly known. They are thought to mostly be monogamous and defend a territory against others of the same species. The nest is constructed by the female in low vegetation and is a large ovoid dome with a side entrance. Two dull eggs are laid. As far as is known only the female incubates the clutch, for a period of between sixteen and twenty-one days. The nestling stage is known to be long, eighteen to twenty-one days.

Status and conservation

Bristlebirds are vulnerable to habitat loss from coastal development and inappropriate fire regimes. Apart from the eastern subspecies of the rufous bristlebird, which are still moderately common within their restricted ranges, populations have declined and become fragmented and the birds have become rare. The western subspecies of the rufous bristlebird is probably extinct.[2][5][6]

References

- 1 2 Del Hoyo, J.; Elliot, A. & Christie D. (editors). (2006). Handbook of the Birds of the World. Volume 12: Picathartes to Tits and Chickadees. Lynx Edicions. ISBN 978-84-96553-42-2

- 1 2 3 4 Higgins, P.J.; & Peter, J.M. (eds). (2003). Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds. Volume 6: Pardalotes to Shrike-thrushes. Oxford University Press: Melbourne. ISBN 0-19-553762-9

- ↑ Christidis, Les; & Boles, Walter E. (2008). Systematics and taxonomy of Australian birds. CSIRO Publishing: Melbourne. ISBN 978-0-643-06511-6

- 1 2 Schodde, R.; & Mason, I.J. (1999). The Directory of Australian Birds: Passerines. CSIRO Publishing: Melbourne. ISBN 0-643-06456-7

- 1 2 Pizzey, Graham; & Knight, Frank. (2003). The Field Guide to the Birds of Australia. HarperCollins. 7th edn. ISBN 0-207-19821-7

- ↑ Morcombe, Michael. (2000). Field Guide to Australian Birds. Steve Parish: Queensland. ISBN 1-876282-10-X