Daniel 7

Daniel 7 (the seventh chapter of the Book of Daniel) tells of Daniel's vision of four world-kingdoms replaced by the kingdom of God. Four beasts come out of the sea, the Ancient of Days sits in judgement over them, and "one like a son of man" is given eternal kingship. An angelic guide interprets the beasts as kingdoms and kings, the last of whom will make war on the "holy ones" of God, but he will be destroyed and the "holy ones" will be given eternal dominion.

It is generally accepted that the Book of Daniel is a product of the mid-2nd century BC.[1] It is an apocalypse, a literary genre in which a heavenly reality is revealed to a human recipient;[2] it is also an eschatology, a divine revelation concerning the moment in which God will intervene in history to usher in the final kingdom.[3] Its context is oppression of the Jews by the Seleucid ruler Antiochus IV, who outlawed Jewish customs and built an altar to Zeus in the Temple (the "abomination of desolation"), sparking a popular uprising which led to the retaking of Jerusalem and the Temple by Judas Maccabeus.[4][5] Chapter 7 introduces the theme of the "four kingdoms", which is that Israel would come under four successive world-empires, each worse than the last, until finally God and his hosts would end oppression and introduce the eternal kingdom.[6]

Summary

In the first year of Belshazzar, king of Babylon, (probably 553 BC), Daniel receives a dream-vision from God. He sees the "great sea" stirred up by the "four winds of heaven," and from the waters emerge four beasts, the first a lion with the wings of an eagle, the second a bear, the third a winged leopard with four heads, and the fourth a beast with ten horns, and a further horn appeared which uprooted three of the ten. As Daniel watches, the Ancient of Days takes his seat on the throne of heaven and sits in judgement in the midst of the heavenly court, the fourth and worst beast is put to death, and a being like a human ("like a son of man") approaches the Ancient One in the clouds of heaven and is given everlasting kingship. A heavenly being explains the vision: the four beasts are four earthly kings (or kingdoms), "but the holy ones of the Most High shall receive and possess the kingdom forever." Regarding the fourth beast, the ten horns are ten kings of this last and greatest earthly kingdom; the eleventh horn (king) will overthrow three kings and make war on the "holy ones of God", and attempt to change the sacred seasons and the law' he will have power "for a time, two times and a half", but when his allotted time is done he will be destroyed, and the holy ones will possess the eternal kingdom.[7]

Structure and composition

Book of Daniel

It is generally accepted that the Book of Daniel originated as a collection of folktales among the Jewish community in Babylon and Mesopotamia in the Persian and early Hellenistic periods (5th to 3rd centuries BC), expanded by the visions of chapters 7-12 in the Maccabean era (mid-2nd century BC).[1] Modern scholarship agrees that Daniel is a legendary figure.[9] It is possible that the name was chosen for the hero of the book because of his reputation as a wise seer in Hebrew tradition.[10] The tales are in the voice of an anonymous narrator, except for chapter 4 which is in the form of a letter from king Nebuchadnezzar.[11] Chapters 2-7 are in Aramaic (after the first few lines of chapter 2 in Hebrew,) and are in the form of a chiasmus,a poetic structure in which the main point or message of a passage is placed in the centre and framed by further repetitions on either side:[12]

- A. (2:4b-49) – A dream of four kingdoms replaced by a fifth

- B. (3:1–30) – Daniel's three friends in the fiery furnace

- C. (4:1–37) – Daniel interprets a dream for Nebuchadnezzar

- C'. (5:1–31) – Daniel interprets the handwriting on the wall for Belshazzar

- B'. (6:1–28) – Daniel in the lions' den

- B. (3:1–30) – Daniel's three friends in the fiery furnace

- A'. (7:1–28) – A vision of four world kingdoms replaced by a fifth

Chapter 7

Chapter 7 is pivotal to the larger structure of the entire book, acting as a bridge between the tales of chapters 1-6 and the visions of 7-12. The use of Aramaic and its place in the chiasm link it to the first half, while the use of Daniel as first-person narrator and its emphasis on visions link it to the second. There is also a temporal shift: the tales in chapters 1-6 have run from Nebuchadnezzar to Belshazzar to Darius, but in chapter 7 we move back to the first year of Belshazzar and the forward movement starts over again, to the third year of Belshazzar and then the third year of Cyrus.[13] Most scholars accept that the chapter was written as a unity, possibly based on an early anti-Hellenistic document from around 300 BC; verse 9 is usually printed as poetry, and may be a fragment of an ancient psalm. The overall structure can be described as follows:[8]

- Introduction (verses 1-2a)

- Vision report: vision of the four beasts; vision of the "little horn"; throne vision; vision of judgement; vision of a figure on the clouds (2b-14)

- Interpretation (15-18)

- Additional clarification of the vision (19-27)

- Conclusion (28)

Genre and themes

Genre

The Book of Daniel is an apocalypse, a literary genre in which a heavenly reality is revealed to a human recipient; such works are characterized by visions, symbolism, an other-worldly mediator, an emphasis on cosmic events, angels and demons, and pseudonymity (false authorship).[2] Apocalypses were common from 300 BC to AD 100, not only among Jews and Christians, but Greeks, Romans, Persians and Egyptians.[14] Daniel, the book's hero, is a representative apocalyptic seer, the recipient of the divine revelation: has learned the wisdom of the Babylonian magicians and surpassed them, because his God is the true source of knowledge; he is one of the maskil, the wise, whose task is to teach righteousness.[14] The book is also an eschatology, meaning a divine revelation concerning the end of the present age, a moment in which God will intervene in history to usher in the final kingdom.[3]

Themes

The overall theme of the Book of Daniel is God's sovereignty over history.[15] Written to encourage Jews undergoing persecution at the hands of Antiochus Epiphanes, the Seleucid king of Syria, the visions of chapters 7-12 predict the end of the earthly Seleucid kingdom, its replacement by the eternal kingdom of God, the resurrection of the dead, and the final judgement.[16] Chapter 7 introduces the specific apocalyptic theme of the "four kingdoms", which is that Israel (or the world) would come under four successive world-empires, each worse than the last, until finally God and his hosts would end oppression and introduce the eternal kingdom.[6]

Interpretation

Historical background: from Babylon to the Greeks

In the late 7th and early 6th centuries BC the Neo-Babylonian empire dominated the Middle East. The Kingdom of Judah began the period as a Babylonian client state, but after a series of rebellions Babylon reduced it to the status of a province and carried off its élite (not all its population) into captivity. This "Babylonian exile" ended in 538 BC when Medes and Persians led by Cyrus the Great conquered Babylon and ushered in the Persian or Achaemenid empire (with the Achaemenids as the ruling dynasty). The Persian empire in turn succumbed to Alexander the Great in the second half of the 4th century, and following Alexander's death in 323 BC his generals divided his empire between themselves. The Roman Empire in turn eventually took control over those parts of the Middle East to the west of Mesopotamia. Palestine fell first under the control of the Ptolemies of Egypt, but around 200 BC it passed to the Seleucids, then based in Syria. Both dynasties were Greek and both promoted Greek culture, usually peacefully, but the Seleucid ruler Antiochus IV, also called Antiochus Epiphanes (reigned 175-164 BC) proved an exception: interpreting Jewish opposition as motivated by religion and culture, he outlawed Jewish customs such as circumcision, kosher dietary restrictions, Sabbath observance, and the Jewish scriptures (the Torah). In his most infamous act he built an altar to Zeus over the altar of burnt offerings in the Temple (the "abomination of desolation"), sparking in 167 BC a massive popular uprising against Hellenic Greek rule which led to the retaking of Jerusalem and the Temple by Judas Maccabeus[4][5] (164 BC).

Imagery and symbolism

The imagery of Daniel 7 comes ultimately from the Canaanite myth of Baʿal's battle with Yamm (lit. "Sea"), symbolic of chaos.[17] The four beasts are chaos monsters[17] which appeared as serpents in the Baʿal Cycle discovered in the ruins of Ugarit in the 1920s. In Daniel 7, composed sometime before Judas Maccabeus purified the temple in 164 BC, they symbolise Babylon, the Medes, Persia and Greece:[18]

- The lion: Babylon. Its transformation into a man reverses Nebuchadnezzar's transformation into a beast in chapter 4, and the "human mind" may reflect his regaining sanity; the "plucked wings" reflect both loss of power and the transformation to a human state.

- The bear: the Medes - compare Jeremiah 51:11 on the Medes attacking Babylon.

- The leopard: Persia. The four heads may reflect the four Persian kings of Daniel 11:2-7.

- The fourth beast: The Greeks and particularly the Seleucids of Syria.

The "ten horns" that appear on the beast stand for the ten Seleucid kings between Seleucus I, the founder of the kingdom, and Antiochus Epiphanes. The "little horn" is Antiochus himself. The "three horns" uprooted by the "little horn" reflect the fact that Antiochus was fourth in line to the throne, and became king after his brother and one of his brother's sons were murdered and the second son exiled to Rome. Antiochus was responsible only for the murder of one of his nephews, but the author of Daniel 7 holds him responsible for all.[19] Anthiochus called himself Theos Epiphanes, "God Manifest", suiting the "arrogant" speech of the little horn.[20]

The next scene is the divine court. Israelite monotheism should have only one throne as there is only one god, but here we see multiple thrones, suggesting the mythic background to the vision. The "Ancient of Days" echoes Canaanite El, but his wheeled throne suggests Ezekiel's mobile throne of God. He is surrounded by fire and an entourage of "ten thousand times ten thousand", an allusion to the heavenly hosts attending Yahweh, the God of Israel, as he rides to battle against his people's enemies. There is no battle, however; instead "the books" are opened and the fate of Israel's enemies is decided by God's sovereign judgement.[21]

The identity of the "one like a son of man" who approaches God on his throne has been much discussed. The usual suggestion is that this figure represents the triumph of the Jewish people over their oppressor; the main alternative view is that he is the angelic leader of God's heavenly host, a connection made explicitly in chapters 10-12, where the reader is told that the conflict on Earth is mirrored by a war in heaven between the Michael, the angelic champion of Israel, assisted by Gabriel, and the angelic "princes" of Greece and Persia; the idea that he is the messiah is sometimes advanced, but Daniel makes no clear reference to the messiah elsewhere.[22]

The "holy ones" seems to refer to the persecuted Jews under Antiochus; the "sacred seasons and the law" are the Jewish religious customs disrupted by him; the "time, two times and a half" is approximately the time of the persecution, from 167 to 164 BC, as well as being half the "perfect number" seven.[23]

"Their kingly power is an everlasting power": the hasidim (the sect of "the pious ones"), who produced the Book of Daniel, believed that the restoration of Jewish worship in the temple would usher in the final age.[24]

Millennial interpretation

Just as scholars note parallels between the prophetic chapters in Daniel and Revelation, so too have historicists since the Protestant Reformation. "The Reformation ... was really born of a twofold discovery--first, the rediscovery of Christ and His salvation; and second, the discovery of the identity of Antichrist and his subversions."[25] "The reformers were unanimous in its acceptance. And it was this interpretation of prophecy that lent emphasis to their reformatory action. It led them to protest against Rome with extraordinary strength and undaunted courage. ... This was the rallying point and the battle cry that made the Reformation unconquerable."[26]

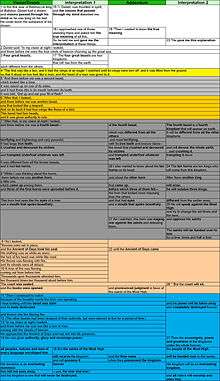

The following is a historicist-based illustration of the parallels.

| Chapter | Parallel sequence of prophetic elements as understood by Historicists[27][28] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Past | Present | Future | ||||

| Daniel 2 | Head Gold (Babylon) |

Chest & 2 arms Silver (Persia) |

Belly and thighs Bronze (Greece) |

2 Legs Iron (Rome) |

2 Feet with toes Clay & Iron |

Rock God's unending kingdom left to no other people |

| Daniel 7 | Winged Lion | Lopsided Bear | 4 Headed/4 Winged Leopard |

Iron toothed Beast w/Little Horn |

Judgment scene Beast w/Horn slain |

A son of man comes in clouds Given everlasting dominion He gives it to the saints. |

Seventh-day Adventists

The Centuriators of Magdeburg, a group of Lutheran scholars in Magdeburg headed by Matthias Flacius, wrote the 12-volume "Magdeburg Centuries" to discredit the papacy and identify the pope as the Antichrist. This was studied by early Seventh-day Adventists and writers Uriah Smith, James White and Ellen White expanded on the general historicist school common among Protestants.

Concerning the "little horn", interpreters of the historicist school (e.g. Adventist) identify the "little horn" as Papal Rome that came to power among the 10 barbarian tribes (the 10 horns) that had broken up the Pagan Roman empire. The reference to changing "times and law" (Daniel 7:25) refers to the change of the Sabbath from Saturday to Sunday. The "time, times and half a time" (Daniel 7:25) was the 1260 years spanning 538 to 1798, when the Roman Church dominated the Christian world. (See Day-year principle for details)

Seventh-day Adventists teach that the Little Horn Power which as predicted rose after the breakup of the Roman Empire is the Papacy. In 533, Justinian, the emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire, legally recognized the bishop (pope) of Rome as the head of all the Christian churches. Because of the Arian domination of some of the Roman Empire by the barbarian tribes, this authority could not be exercised by the bishop of Rome. Finally, in 538, Justinian's general Belisarius routed the Ostrogoths, the last of the barbarian kingdoms, from the city of Rome and the bishop of Rome could begin establishing his universal civil authority. So, by the military intervention of the Eastern Roman Empire, the bishop of Rome became all-powerful throughout the area of the old Roman Empire.

Like many reformation-era Protestant leaders, the writings of Adventist pioneer Ellen White speak against the Catholic Church as a fallen church and in preparation for a nefarious eschatological role as the antagonist against God's true church and that the pope is the Antichrist. Many Protestant reformers such as Martin Luther, John Knox, William Tyndale and others held similar beliefs about the Catholic Church and the papacy when they broke away from the Catholic Church during the reformation.[29]

Ellen White writes,

His word has given warning of the impending danger; let this be unheeded, and the Protestant world will learn what the purposes of Rome really are, only when it is too late to escape the snare. She is silently growing into power. Her doctrines are exerting their influence in legislative halls, in the churches, and in the hearts of men. She is piling up her lofty and massive structures in the secret recesses of which her former persecutions will be repeated. Stealthily and unsuspectedly she is strengthening her forces to further her own ends when the time shall come for her to strike. All that she desires is vantage ground, and this is already being given her. We shall soon see and shall feel what the purpose of the Roman element is. Whoever shall believe and obey the word of God will thereby incur reproach and persecution.[30]

Seventh-day Adventists view the length of time the apostate church unbridled power was permitted to rule as shown in Daniel 7:25 "The little horn would rule a time and times and half a time" or 1,260 years. The papacy ruled supremely in Europe from 538 when the last of the Arian tribes was forced out of Rome and into oblivion, until 1798 when the French general Berthier took the pope captive, which history records a period of 1,260 years.

Methodists

Adam Clarke's commentary published in 1831 supports the interpretation that the little horn is Papal Rome by this comment "Among Protestant writers this is considered to be the popedom."[31]

He stated that the 1260-year period should commence in 755, the year Pepin the Short actually invaded Lombard territory, resulting in the Pope's elevation from a subject of the Byzantine Empire to an independent head of state.[32] The Donation of Pepin, which first occurred in 754 and again in 756 gave to the Pope temporal power of the Papal States. His time line, which began in 755 will end in 2015. But his introductory comments on Daniel 7 added 756 as an alternative commencement date [33] Based on this, commentators anticipate the end of the Papacy in 2016:

"As the date of the prevalence and reign of antichrist must, according to the principles here laid down, be fixed at AD 756, therefore the end of this period of his reign must be AD 756 added to 1260; equal to 2016, the year of the Christian era set by infinite wisdom for this long-prayed-for event. Amen and amen!" [34][35]

Futurist views

In the Futurist view, the "little horn" is identified as the future antichrist who will rise to power through the "revived Roman Empire"(the fourth beast). The "time, times and half a time" (Daniel 7:25) is taken as a literal 3½ year period corresponding to the last half of the 7 year tribulation within the 70th week of Daniel 9:24-27.

Appendix

Over the centuries Bible Scholars have identified specific kingdoms as fulfillment of the beast and horn symbols as illustrated in the following table.

| Interpretations of the kingdoms of Daniel 7 by Biblical expositors from the 1st to 19th centuries | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

Citations

- 1 2 Collins 1984, p. 29,34-35.

- 1 2 Crawford 2000, p. 73.

- 1 2 Carroll 2000, p. 420-421.

- 1 2 Bandstra 2008, p. 449.

- 1 2 Aune 2010, p. 15-19.

- 1 2 Cohen 2006, p. 188-189.

- ↑ Levine 2003, p. 1247-1249.

- 1 2 Collins 1984, p. 74-75.

- ↑ Collins 1984, p. 28.

- ↑ Redditt 2008, p. 176-177,180.

- ↑ Wesselius 2002, p. 295.

- ↑ Redditt 2009, p. 177.

- ↑ Hebbard 2009, p. 23.

- 1 2 Davies 2006, p. 397-406.

- ↑ Levine 2010, p. 1234.

- ↑ Nelson 2000, p. 311-312.

- 1 2 Collins 1984, p. 77.

- ↑ Levine 2010, p. p.1247 footnotes.

- ↑ Levine 2010, p. 1247-1248 footnotes.

- ↑ Seow 2003, p. 106.

- ↑ Seow 2003, p. 106-107.

- ↑ Collins 1998, p. 101-103.

- ↑ Levine 2010, p. 1248-1249, footnotes.

- ↑ Hammer & 1976 p.72.

- ↑ Froom 1948, p. 243

- ↑ Froom 1948, pp. 244, 245

- ↑ Smith 1944

- ↑ Anderson 1975

- ↑ The Antichrist and the Protestant Reformation

- ↑ White, Ellen G. (1999) [1888]. "Enmity Between Man and Satan". The Great Controversy: Between Christ and Satan. The Ellen G. White Estate. p. 581. ISBN 0-8163-1923-5. Retrieved 2006-06-06.

- ↑ Adam Clarke's Commentary of Daniel, Chapter 7 (see notes on verse 8)

- ↑ Earle, abridged by Ralph (1831). Adam Clarke's commentary on the Bible (Reprint 1967 ed.). Grand Rapids, Mich.: World Pub. ISBN 9780529106346.

- ↑ Adam Clarke "The Holy Bible" New York: Lane and Scott (1850) Vol. IV, Introduction to Chapter VII. Page 592 "It will be proper to remark that the period of a time, times, and a half, mentioned in the twenty-fifth verse are the duration of the dominion of the little horn that made war with the saints, (generally supposed to be a symbolic representation of the papal power,) had most probably its commencement in A.D. 755 or 756, when Pepin, king of France, invested the pope with temporal power. This hypothesis will bring the conclusion of the period to about the year of Christ 2000, a time fixed by Jews and Christians for some remarkable revolution; when the world, as they suppose, will be renewed, and the wicked cease from troubling the Church, and the saints of the Most High have dominion over the whole habitable globe."

- ↑ Freeborn Garretson Hibbard "Eschatology: Or, The Doctrine of the Last Things" New York: Hunt & Eaton (1890) page 84

- ↑ D. D. Whedon "The Methodist Quarterly Review" New York: Carlton & Porter (1866) Article V page 256

- ↑ After table in Froom 1950, pp. 456–7

- ↑ After table in Froom 1950, pp. 894-75

- 1 2 After table in Froom 1948, pp. 528–9

- ↑ After table in Froom 1948, pp. 784–5

- ↑ After table in Froom 1946, pp. 252–3

- ↑ After table in Froom 1946, pp. 744–5

Bibliography

- Aune, David E. (2010). "The World of Roman Hellenism". In Aune, David E. The Blackwell Companion to The New Testament. John Wiley & Sons.

- Bandstra, Barry L. (2008). Reading the Old Testament: An Introduction to the Hebrew Bible. Wadsworth Publishing Company.

- Boyer, Paul S. (1992). When Time Shall Be No More: Prophecy Belief in Modern American Culture. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-95129-8.

- Brettler, Mark Zvi (2005). How To Read the Bible. Jewish Publication Society.

- Cohn, Shaye J.D. (2006). From the Maccabees to the Mishnah. Westminster John Knox Press.

- Collins, John J. (1984). Daniel: With an Introduction to Apocalyptic Literature. Eerdmans.

- Collins, John J. (1998). The Apocalyptic Imagination: An Introduction to Jewish Apocalyptic Literature. Eerdmans.

- Collins, John J. (2002). "Current Issues in the Study of Daniel". In Collins, John J.; Flint, Peter W.; VanEpps, Cameron. The Book of Daniel: Composition and Reception. I. BRILL.

- Collins, John J. (2003). "From Prophecy to Apocalypticism: The Expectation of the End". In McGinn, Bernard; Collins, John J.; Stein, Stephen J. The Continuum History of Apocalypticism. Continuum.

- Coogan, Michael (2009). A Brief Introduction to the Old Testament. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 400.

- Crawford, Sidnie White (2000). "Apocalyptic". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans.

- Davidson, Robert (1993). "Jeremiah, Book of". In Metzger, Bruce M.; Coogan, Michael D. The Oxford Companion to the Bible. Oxford University Press.

- Davies, Philip (2006). "Apocalyptic". In Rogerson, J. W.; Lieu, Judith M. The Oxford Handbook of Biblical Studies. Oxford Handbooks Online.

- DeChant, Dell (2009). "Apocalyptic Communities". In Neusner, Jacob. World Religions in America: An Introduction. Westminster John Knox Press.

- Dunn, James D.G. (2002). "The Danilic Son of Man in the New Testament". In Collins, John J.; Flint, Peter W.; VanEpps, Cameron. The Book of Daniel: Composition and Reception. BRILL.

- Froom, Le Roy Edwin (1950). Early Church Exposition, Subsequent Deflections, and Medieval Revival. The Prophetic Faith of our Fathers: The Historical Development of Prophetic Interpretation. 1. The Review and Herald Publishing Association. p. 1006.

- Froom, Le Roy Edwin (1948). Pre-Reformation and Reformation Restoration, and Second Departure. The Prophetic Faith of our Fathers: The Historical Development of Prophetic Interpretation. 2. The Review and Herald Publishing Association. p. 863.

- Froom, Le Roy Edwin (1946). PART I, Colonial and Early National American Exposition. PART II, Old World Nineteenth Century Advent Awakening. The Prophetic Faith of our Fathers: The Historical Development of Prophetic Interpretation. 3. The Review and Herald Publishing Association. p. 802.

- Gallagher, Eugene V. (2011). "Millennialism, Scripture, and Tradition". In Wessinger, Catherine. The Oxford Handbook of Millennialism. Oxford University Press.

- Goldingay, John J. (2002). "Daniel in the Context of OT Theology". In Collins, John J.; Flint, Peter W.; VanEpps, Cameron. The Book of Daniel: Composition and Reception. II. BRILL.

- Grabbe, Lester L. (2010). An Introduction to Second Temple Judaism: History and Religion of the Jews in the Time of Nehemiah, the Maccabees, Hillel, and Jesus. Continuum.

- Grabbe, Lester L. (2002). Judaic Religion in the Second Temple Period: Belief and Practice from the Exile to Yavneh. Routledge.

- Grabbe, Lester L. (2002). "A Dan(iel) For All Seasons". In Collins, John J.; Flint, Peter W.; VanEpps, Cameron. The Book of Daniel: Composition and Reception. BRILL.

- Hammer, Raymond (1976). The Book of Daniel. Cambridge University Press.

- Harrington, Daniel J. (1999). Invitation to the Apocrypha. Eerdmans.

- Hebbard, Aaron B. (2009). Reading Daniel as a Text in Theological Hermeneutics. Wipf and Stock Publishers.

- Hill, Andrew E. (2009). "Daniel-Malachi". In Longman, Tremper; Garland, David E. The Expositor's Bible Commentary. 8. Zondervan.

- Hill, Charles E. (2000). "Antichrist". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans.

- Holbrook, Frank B. (1986). The Seventy Weeks, Leviticus, and the Nature of Prophecy (Volume 3 of Daniel and Revelation Committee Series ed.). Biblical Research Institute, General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists. ISBN 0925675024.

- Horsley, Richard A. (2007). Scribes, Visionaries, and the Politics of Second Temple Judea. Presbyterian Publishing Corp.

- Knibb, Michael (2009). Essays on the Book of Enoch and Other Early Jewish Texts and Traditions. BRILL.

- Knibb, Michael (2002). "The Book of Daniel in its Context". In Collins, John J.; Flint, Peter W.; VanEpps, Cameron. The Book of Daniel: Composition and Reception. BRILL.

- Koch, Klaus (2002). "Stages in the Canonization of the Book of daniel". In Collins, John J.; Flint, Peter W.; VanEpps, Cameron. The Book of Daniel: Composition and Reception. BRILL.

- Kratz, Reinhard (2002). "The Visions of Daniel". In Collins, John J.; Flint, Peter W.; VanEpps, Cameron. The Book of Daniel: Composition and Reception. BRILL.

- Levine, Amy-Jill (2010). "Daniel". In Coogan, Michael D.; Brettler, Marc Z.; Newsom, Carol A. The new Oxford annotated Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical books : New Revised Standard Version. Oxford University Press.

- Lucas, Ernest C. (2005). "Daniel, Book of". In Vanhoozer, Kevin J.; Bartholomew, Craig G.; Treier, Daniel J. Dictionary for Theological Interpretation of the Bible. Baker Academic.

- Mangano, Mark (2001). Esther & Daniel. College Press.

- Matthews, Victor H.; Moyer, James C. (2012). The Old Testament: Text and Context. Baker Books.

- Nelson, William B. (2000). "Daniel". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans.

- Nelson, William B. (2013). Daniel. Baker Books.

- Newsom, Carol A.; Breed, Brennan W. (2014). Daniel: A Commentary. Presbyterian Publishing Corp.

- Nichol, F., ed. (1954). "chronology chart". SDA Bible Commentary. pp. 326–327.

- Niskanen, Paul (2004). The Human and the Divine in History: Herodotus and the Book of Daniel. Continuum.

- Pasachoff, Naomi E.; Littman, Robert J. (2005). A Concise History of the Jewish People. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Portier-Young, Anathea E. (2013). Apocalypse Against Empire: Theologies of Resistance in Early Judaism. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Provan, Iain (2003). "Daniel". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Redditt, Paul L. (2009). Introduction to the Prophets. Eerdmans.

- Reid, Stephen Breck (2000). "Daniel, Book of". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans.

- Rowland, Christopher (2007). "Apocalyptic Literature". In Hass, Andrew; Jasper, David; Jay, Elisabeth. The Oxford Handbook of English Literature and Theology. Oxford University Press.

- Ryken,, Leland; Wilhoit, Jim; Longman, Tremper (1998). Dictionary of Biblical Imagery. InterVarsity Press.

- Sacchi, Paolo (2004). The History of the Second Temple Period. Continuum.

- Schwartz, Daniel R. (1992). Studies in the Jewish Background of Christianity. Mohr Siebeck.

- Seow, C.L. (2003). Daniel. Westminster John Knox Press.

- Schiffman, Lawrence H. (1991). From Text to Tradition: A History of Second Temple and Rabbinic Judaism. KTAV Publishing House.

- Spencer, Richard A. (2002). "Additions to Daniel". In Mills, Watson E.; Wilson, Richard F. The Deuterocanonicals/Apocrypha. Mercer University Press.

- Towner, W. Sibley (1993). "Daniel". In Coogan, Michael D.; Metzger, Bruce M. The Oxford Companion to the Bible. Oxford University Press.

- Towner, W. Sibley (1984). Daniel. Westminster John Knox Press.

- VanderKam, James C. (2010). The Dead Sea Scrolls Today. Eerdmans.

- VanderKam, James C.; Flint, Peter (2013). The meaning of the Dead Sea scrolls: their significance for understanding the Bible, Judaism, Jesus, and Christianity. HarperCollins.

- Weber, Timothy P. (2007). "Millennialism". In Walls, Jerry L. The Oxford Handbook of Eschatology. Oxford University Press.

- Wesselius, Jan-Wim (2002). "The Writing of Daniel". In Collins, John J.; Flint, Peter W.; VanEpps, Cameron. The Book of Daniel: Composition and Reception. BRILL.

- White, Ellen (2014). Yahweh's Council: Its Structure and Membership. Mohr Siebeck.