Damodar Pande

| Mulkaji Saheb Damodar Pandey | |

|---|---|

| श्री मूलकाजी साहेब दामोदर पाण्डे | |

| Mukhtiyar of Nepal | |

| Mulkaji | |

|

In office 1799 A.D. – 1804 A.D. | |

| Monarch | Rana Bahadur Shah |

| Preceded by | position established |

| Succeeded by | Bhimsen Thapa |

| Commander-in-Chief | |

| Preceded by | Kirtiman Singh Basnyat |

| Succeeded by | Bhimsen Thapa, Amar Singh Thapa |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1752 A.D. |

| Died | 1804 A.D. |

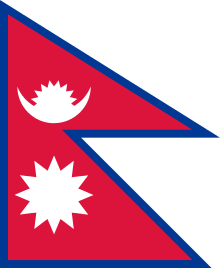

| Nationality | Nepali |

| Children | Rana Jang Pandey |

| Father | Kalu Pande |

| Religion | Hindu, Kshetri |

Damodar Pande (Nepali: दामोदर पाँडे वा दामोदर पाण्डे) (1752 – March 13, 1804) was the Mukhtiyar from 1799 to 1804. He was the youngest son of famous Kaji of Prithivi Narayan Shah Kalu Pande. He was born in 1752 in Gorkha. Damodar Pande was one of the commanders during the Sino-Nepalese War and in Nepal-Tibet War. And he was among successful Gorkhali warriors sent towards the east by Prithivinarayan Shah.

Rise in power

Rana Bahadur Shah, the King of Nepal from 1777 to 1799, was shocked and saddened by the death of his mistress in 1799. Owing to his irrational behavior, he was forced to resign by the citizens. He left the throne to his one and half year old son Girvan Yuddha Shah and fled to Banaras along with his followers like Bhimsen Thapa, Dalbhanjan Pande and his wife, the queen Rajrajeshwori.[1]

Damodar Pande took over the administration and became the Mukhtiyar of Nepal. He always tried to protect king Girvan Yuddha Shah and keep Rana Bahadur off of Nepal. However, in 1804, March 4, the former king came back and took over the post of Mukhtiyar. Damodar Pande was then beheaded and killed in Thankot.[2]

Decline from power

After Rajrajeshowri took over the regency, she was pressured by Knox to pay the annual pension of 82,000 rupees to the ex-King as per the obligations of the treaty,[3] which paid off the vast debt that Rana Bahadur Shah had accumulated in Varanasi due to his spendthrift habits.[note 1][6][7][4] The Nepalese court also felt it prudent to keep Rana Bahadur in isolation in Nepal itself, rather than in the British controlled India, and that paying off Rana Bahadur's debts could facilitate his return at an opportune moment.[7] Rajrajeshowri's presence in Kathmandu also stirred unrest among the courtiers that aligned themselves around her and Subarnaprabha. Sensing an imminent hostility, Knox aligned himself with Subarnaprabha and attempted to interfere with the internal politics of Nepal.[8] Getting a wind of this matter, Rajrajeshowri dissolved the government and elected new ministers, with Damodar Pande as the mul kaji, while the Resident Knox, finding himself persona non grata and the objectives of his mission frustrated, voluntarily left Kathmandu to reside in Makwanpur citing a cholera epidemic.[8][3] Subarnaprabha and the members of her faction were arrested.[8]

Such open display of anti-British feelings and humiliation prompted the Governor General of the time Richard Wellesley to recall Knox to India and unilaterally suspend the diplomatic ties.[9] The Treaty of 1801 was also unilaterally annulled by the British on 24 January 1804.[3][10][11][9] The suspension of diplomatic ties also gave the Governor General a pretext to allow the ex-King Rana Bahadur to return to Nepal unconditionally.[10][9]

As soon as they received the news, Rana Bahadur and his group proceeded towards Kathmandu. Some troops were sent by Kathmandu Durbar to check their progress, but the troops changed their allegiance when they came face to face with the ex-King.[12] Damodar Pande and his men were arrested at Thankot where they were waiting to greet the ex-King with state honors and take him into isolation.[12][11] After Rana Bahadur's reinstatement to power, he started to extract vengeance on those who had tried to keep him in exile.[13] He exiled Rajrajeshhwori to Helambu, where she became a Buddhist nun, on the charge of siding with Damodar Pande and colluding with the British.[14][15] Damodar Pande, along with his two eldest sons, who were completely innocent, were executed on 13 March 1804; similarly some members of his faction were tortured and executed without any due trial, while many others managed to escape to India.[note 2][16][15] Rana Bahadur also punished those who did not help him while in exile. Among them was Prithvipal Sen, the king of Palpa, who was tricked into imprisonment, while his kingdom forcefully annexed.[17][18] Subarnaprabha and her supporters were released and given a general pardon. Those who had helped Rana Bahadur to return to Kathmandu were lavished with rank, land, and wealth. Bhimsen Thapa was made a second kaji; Ranjit Pande, who was the father-in-law of Bhimsen's brother, was made the mul kaji; Sher Bahadur Shah, Rana Bahadur's half-brother, was made the mul chautariya; while Rangnath Paudel was made the raj guru (royal spiritual preceptor).[17][19]

Death

In 1804, March 1, the former king came back and took over the post of Mukhtiyar. March 13, Damodar Pande was then beheaded after he was imprisoned in Bhadrakali.[20][21]

Notes

- ↑ Rana Bahadur had borrowed a lot of money from many different people: Rs 60,000 from Dwarika Das; Rs 100,000 from Raja Shivalal Dube; Rs 1,400 from Ambasankar Bhattnagar. Similarly, he had borrowed a lot of money from the East India Company as well. However, Rana Bahadur was reckless in the manner he spent the borrowed money. For instance, he had once given an alms of Rs 500 to a Brahmin.[4] For more details see [5]

- ↑ Among those who managed to escape to India were Damodar Pande's sons Karbir Pande and Ranjang Pande.[16]

References

- ↑ "Advanced history of Nepal" by Tulasī Rāma Vaidya

- ↑ Nepal:The Struggle for Power (Sourced to U.S. Library of Congress)

- 1 2 3 Amatya 1978.

- 1 2 Nepal 2007, pp. 54–55.

- ↑ Regmi 1987a; Regmi 1987b; Regmi 1988.

- ↑ Pradhan 2012, p. 14.

- 1 2 Acharya 2012, pp. 42–43, 48.

- 1 2 3 Acharya 2012, p. 43.

- 1 2 3 Acharya 2012, p. 45.

- 1 2 Pradhan 2012, pp. 14, 25.

- 1 2 Nepal 2007, p. 56.

- 1 2 Acharya 2012, pp. 49–55.

- ↑ Acharya 2012, pp. 54–57.

- ↑ Acharya 2012, p. 57.

- 1 2 Nepal 2007, p. 57.

- 1 2 Acharya 2012, p. 54.

- 1 2 Nepal 2007, p. 58.

- ↑ Acharya 2012, pp. 56,80–83.

- ↑ Acharya 2012, p. 55.

- ↑ Nepal:The Struggle for Power (Sourced to U.S. Library of Congress)

- ↑ The Bloodstained Throne Struggles for Power in Nepal (1775-1914) - Baburam Acharya