Dalhousie University

| |

| Latin: Universitas Dalhousiana | |

Former names |

Dalhousie College (1818–1863) The Governors of Dalhousie College and University (1863–1996) |

|---|---|

| Motto | Latin: Ora et Labora |

Motto in English | Pray and work |

| Type | Public university |

| Established | 1818 (198 years ago as of 2016) |

| Endowment | $537.8 million[1] |

| Chancellor | Anne McLellan |

| President | Richard Florizone |

Academic staff | 867; full-time clinical dentistry & medicine (274); part-time (826). |

| Students | 18,564[2] |

| Undergraduates | 14,650 |

| Postgraduates | 3,914 |

| Location |

, Nova Scotia, Canada |

| Campus | |

| Colours | Black and Gold |

| Sports | |

| Nickname |

|

| Affiliations | |

| Website |

dal |

| |

Dalhousie University (commonly known as Dal) is a public research university in Nova Scotia, Canada, with three campuses in Halifax, a fourth in Bible Hill, and medical teaching facilties in Saint John, New Brunswick. Dalhousie offers more than 4,000 courses and 180 degree programs in twelve undergraduate, graduate, and professional faculties.[3] The university is a member of the U15, a group of research-intensive universities in Canada.

Dalhousie was established as a nonsectarian college in 1818 by the eponymous Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia, George Ramsay, 9th Earl of Dalhousie. The college did not hold its first class until 1838, until then operating sporadically due to financial difficulties. It reopened for a third time in 1863 following a reorganization that brought a change of name to "The Governors of Dalhousie College and University". The university formally changed its name to "Dalhousie University" in 1997 through provincial legislation, the same legislation that merged the institution with the Technical University of Nova Scotia.

The university's notable alumni include a Nobel Prize winner, two Canadian Prime Ministers, two Herzberg Prize winners, a NASA astronaut who was the first American woman to walk in space, 90 Rhodes Scholars, and a range of other top government officials, academics, and business leaders. The university ranked 235th in the 2014 QS World University Rankings,[4] 226-250th in the 2014-2015 Times Higher Education World University Rankings,[5] and 201–300th in the 2014 Academic Ranking of World Universities.[6] Dalhousie is a centre for marine research, and is host to the headquarters of the Ocean Tracking Network.

The Dalhousie library system operates the largest library in Atlantic Canada, and holds the largest collection of agricultural resource material in the region. The university operates a total of fourteen residences. There are currently two student unions that represent student interests at the university: the Dalhousie Student Union and the Dalhousie Association for Graduate Students. Dalhousie's varsity teams, the Tigers, compete in the Atlantic University Sport conference of Canadian Interuniversity Sport. Dalhousie's Faculty of Agriculture varsity teams are called the Dalhousie Rams, and compete in the ACAA and CCAA. Dalhousie is a coeducational university with more than 18,000 students and 110,000 alumni.

History

Dalhousie was founded as the Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia George Ramsay, 9th Earl of Dalhousie desired a non-denominational college in Halifax. Financing largely came from customs duties collected by a previous Lieutenant Governor, John Coape Sherbrooke, during the War of 1812 occupation of Castine, Maine;[lower-alpha 1] Sherbrooke invested GBP£7,000 as an initial endowment and reserved £3,000 for the physical construction of the college.[7] The college was established in 1818, though it faltered shortly after as Ramsay left Halifax to serve as the Governor General of British North America.[8] The school was structured upon the principles of the University of Edinburgh, where lectures were open to all, regardless of religion or nationality. The University of Edinburgh was located near Ramsay's home in Scotland.[9]

In 1821 Dalhousie College was officially incorporated by the Nova Scotia House of Assembly under the 1821 Act of Incorporation.[10] The college did not hold its first class until 1838; operation of the college was intermittent and no degrees were awarded.[8] In 1841 an Act of the Nova Scotia House of Assembly conferred university powers on Dalhousie.[11]

In 1863 the college opened for a third time and was reorganized by another legislative act, which added "University" to the school's name: "The Governors of Dalhousie College and University".[12][13] Dalhousie reopened with six professors and one tutor. When it awarded its first degrees in 1866 the student body consisted of 28 students working toward degrees and 28 occasional students.[8] The first female graduate was Margaret Florence Newcome from Grafton, Nova Scotia, who earned her degree in 1885.[14] Despite the reorganization and an increase in students, money continued to be a problem for the institution. In 1879, amid talks of closure due to the university's dire financial situation, a wealthy New York publisher with Nova Scotian roots, George Munro, began to donate to the university; Munro was brother-in-law to Dalhousie's Board of Governors member John Forrest. Munro is credited with rescuing Dalhousie from closure, and in honour of his contributions Dalhousie observes a university holiday called George Munro Day on the first Friday of each February.[15]

Originally located at the space now occupied by Halifax City Hall, the college moved in 1886 to Carleton Campus and spread gradually to Studley Campus.[8] Dalhousie grew steadily during the 20th century. From 1889 to 1962 the Halifax Conservatory was affiliated with and awarded degrees through Dalhousie.[16] In 1920 several buildings were destroyed by fire on the campus of the University of King's College in Windsor, Nova Scotia. Through a grant from the Carnegie Foundation, King's College relocated to Halifax and entered into a partnership with Dalhousie that continues to this day.[17]

Dalhousie expanded on 1 April 1997 when provincial legislation mandated an amalgamation with the nearby Technical University of Nova Scotia. This merger saw reorganization of faculties and departments to create the Faculty of Engineering, Faculty of Computer Science and the Faculty of Architecture and Planning.[18] From 1997 to 2000, the Technical University of Nova Scotia operated as a constituent college of Dalhousie called Dalhousie Polytechnic of Nova Scotia (DalTech) until the collegiate system was dissolved.[19] The legislation that merged the two schools also formally changed the name of the institution to its present form, Dalhousie University.[20] On 1 September 2012 the Nova Scotia Agricultural College merged into Dalhousie to form a new Faculty of Agriculture, located in Bible Hill, Nova Scotia.[21][22]

Campuses

Dalhousie has three campuses within the Halifax Peninsula and a fourth, the Agricultural Campus, in Bible Hill, Nova Scotia. The largest, Studley Campus, serves as the primary campus; it houses the majority of the university's academic buildings such as faculties, athletic facilities, and the university's Student Union Building.[23] The campus is largely surrounded by residential neighbourhoods. Robie Street divides it from the adjacent Carleton Campus, which houses the faculties of dentistry, medicine, and other health profession departments. The campus is adjacent to two large teaching hospitals affiliated with the school: the IWK Health Centre and the Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre.[23]

Sexton Campus in Downtown Halifax hosts the engineering, architecture and planning faculties. Sexton Campus served as the campus of the Technical University of Nova Scotia prior to amalgamation.[23] The Agricultural Campus in Bible Hill, a suburban community of Truro, Nova Scotia, served as the campus for the Nova Scotia Agricultural College prior to its merger with Dalhousie in 2011.[24]

The buildings at Dalhousie vary in age from Hart House, which was completed in 1864, to the Collaborative Health Education Building, completed in 2015.[25][26] The original building of Dalhousie University was completed in 1824 on Halifax's Grand Parade.[27] It was demolished in 1885 when the university outgrew the premises, and the City of Halifax sought possession of the entire Grand Parade. Halifax City Hall presently occupies the site of the original Dalhousie College.[27]

Libraries and museums

The university has five libraries. The largest, Killam Memorial Library, opened in 1971. It is the largest academic library in Atlantic Canada with over one million books and 40,000 journals. The library's collection largely serves the faculties of arts and social sciences, sciences, management, and computer science.[28] The W. K. Kellogg Health Science Library provides services largely for the faculties of dentistry, medicine, and other health professions.[29] The Sexton Design & Technology Library is located within Sexton Campus. Its collection largely serves those in the faculties of engineering, architecture and planning, and houses the university's rare books collection.[30] The Sir James Dunn Law Library holds the university's collection of common law materials, legal periodicals, as well as books on international law, health law, and environmental law.[31] MacRae Library is located at the university's Agricultural Campus, and has the largest collection of agricultural resource material in Atlantic Canada.[32] The Dalhousie University Archives houses official records of, or relating to, or people/activities connected with Dalhousie University and its founding institutions. The archives also houses material related to theatre, business and labour in Nova Scotia. The collection consists of manuscripts, texts, photographs, audio-visual material, microfilm, music, and artifacts. [33]

The biology department operates the Thomas McCulloch Museum. The most notable of the museum's exhibits is its preserved birds collection. Other exhibits include its collection of lorenzen ceramic mushrooms, its coral and shell collection, and its butterfly and insect collection.[34] The museum's namesake Thomas McCulloch was a Scottish Presbyterian minister who served as Dalhousie's first president and created the Audubon mounted bird collection which is now housed at the museum.[35]

The Dalhousie Art Gallery is both a public gallery and an academic support unit housed since 1971 on the lowest level of the Dalhousie Arts Centre. Admission is free of charge. It is host to a permanent collection of over 1000 works.[36] Some of the outdoor sculptures around the campus are part of this collection, such as the distinctive Marine Venus which has sat in the median of University Avenue since 1969.[37] A notable exhibition from the Dalhousie Art Gallery includes "Archives of the Future" (March – April 2016) exploring the relationship between art creation and commerce with work by artists Zachary Gough, Dawn Georg, Sharlene Bamboat, Katie Vida and Dana Claxton.[38]

Housing and student facilities

The university has eleven student residences throughout its Halifax campuses: Eliza Ritchie Hall, Gerard Hall, Howe Hall, LeMarchant Place, Mini Rez, O'Brien Hall, Residence Houses, Risley Hall, Shirreff Hall, Glengary Apartments, and Graduate House.[39] The largest, Howe Hall in Studley Campus, houses 716 students during the academic year. Howe Hall's most recent addition to the residence is called Fountain. It is the only residence in Howe Hall to have a sink in every room.[40] The university also operates three residences in its Agricultural Campus: Chapman House, Fraser House, and Truman House. The largest residence in the Agricultural Campus is Chapman House, housing 125 students during the academic year.[41] The residences are represented by a Residence Council responsible for resident concerns, providing entertainment services, organizing events, and upholding rules and regulations.[42]

The Student Union Building serves as the main student activity centre. Completed in 1968, it is located in the Studley Campus. The Student Union building hosts a number of student societies and organization offices, most notably the Dalhousie Student Union.[23][43] The building houses five restaurants, both independently owned and international franchises such as Tim Hortons.[44]

Sustainability

Dalhousie University is actively involved in sustainability issues and has received a number of sustainability awards and recognition for academic programs, university operations, and research. In 2015, Dalhousie received a GOLD rating from AASHE STARS (Version 2.0).[45] In 2009, the university signed the University and College Presidents’ Climate Change Statement of Action for Canada to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases.[46] Dalhousie is also a signatory of UNEP's International Declaration on Cleaner Production.[47] In 1999, the university signed the Talloires Declaration, which committed Dalhousie and other higher education institutions to developing, creating, supporting, and maintaining sustainability.[47]

In 2008, the College of Sustainability,[48] the Office of Sustainability,[49] and the Dalhousie Student Union Sustainability Office[50] were formed. During 2008, the President’s Advisory Council on Sustainability was also created. The council meets quarterly to discuss pan-university sustainability issues[48]. Dalhousie’s international award-winning College of Sustainability offers an undergraduate Major in Environment, Sustainability and Society (ESS) integrating with seven bachelor's degrees and forty subjects across five faculties. The College of Sustainability offers a virtual and a physical space for the intersection of interdisciplinary collaboration, conversation, and teaching with a core of cross-appointed Dalhousie faculty members joined by visiting fellows, distinguished guest lecturers, community leaders, and environmental advocates. In addition, the Sustainability Leadership Certificate program offers students the opportunity to participate in an engaged exploration of personal and group leadership and empowers their sense of personal agency to address environmental and social change.

The Office of Sustainability spearheads a number of campus sustainability plans and policies including the Climate Change Plan, Natural Environment Plan, and Green Building policy. A number of initiatives have been developed and implemented with campus partners including numerous energy and water retrofits, residence Eco-Olympics competition, an Employee Sustainability Leadership Program, and an Employee Bus Pass. The Dalhousie Student Union Sustainability Office promotes awareness and behaviour change. DSUSO hosts “Green Week,” the “Green Gala” and the “Greenie Awards” to celebrate campus accomplishments on sustainability. A number of student societies are also active in sustainability issues from on-campus gardening and food security to environmental law.

Controversy

Several student groups on campus have pointed out that Dalhousie’s significant investment of its endowment funds in the fossil fuel industry contradicts its apparent commitment to sustainability issues, and have criticized the university’s efforts to brand itself as a leader in the field as greenwashing. Most prominent among these groups is Divest Dal, who since 2013 have called for a increased endowment transparency and complete divestment of Dalhousie’s endowment from the top 200 fossil fuel companies within four years.[51] Of Dalhousie’s $500-million endowment, about $20 million is currently invested in fossil fuels.[52] Divest Dal has argued that continuing to invest in fossil companies in the face of the global injustice wrought by climate change, the Paris Agreement, and climate science represents unprincipled kowtowing to corporate interests on the part of university’s administration. According to the group, the University has a responsibility to instead invest in a future that aligns with its sustainable veneer, and the beliefs and needs of its students, faculty and staff. Faced with overwhelming support for divestment from thousands of students,[53] Divest Dal, the Dalhousie Student Union,[54] and recently the university’s Senate,[55] the Board of Governors at the university continues to avoid the question of divestment after having voted against it in 2014.

Administration

University governance is conducted through the Board of Governors and the Senate, both of which were given much of their present power in the Unofficial Consolidation of an Act for the Regulation and Support of Dalhousie College in Chapter 24 of the Acts of 1863. This statute replaced ones from 1820, 1823, 1838, 1841 and 1848, and has since been supplemented 11 times, most recently in 1995.[13] The Board is responsible for conduct, management, and control of the university and of its property, revenues, business, and affairs. Board members, known as Governors of the Board, include the university's chancellor, president, and 25 other members. Members include people from within the university community such as four approved representatives from Dalhousie Student Union, and those in the surrounding community, such as the Mayor of Halifax.[13] The Senate is responsible for the university's academics, including standards for admission and qualifications for degrees, diplomas, and certificates.[13] The Senate consists of 73 positions granted to the various faculty representatives, academic administrators, and student representatives.[56]

The president acts as the chief executive officer and is responsible to the Board of Governors and to the Senate for the supervision of administrative and academic works. Richard Florizone is the 11th president of the university, and has served since 2013.[57] Thomas McCulloch served as the first president when the office was created in 1838. John Forrest was the longest-serving president, holding the office from 1885 to 1911.[58]

Affiliated institutions

The University of King's College is a post-secondary institution in Halifax affiliated with Dalhousie. Established in 1789, it was the first post-secondary institution in English Canada and the oldest English-speaking Commonwealth university outside the United Kingdom.[59] The University of King's College was formerly an independent institution located in Windsor, Nova Scotia, until 1920, when a fire ravaged its campus. To continue operation, the University of King's College accepted a generous grant from the Carnegie Foundation, although the terms of the grant required that it move to Halifax and enter into association with Dalhousie.[59] Under the agreement, King's agreed to pay the salaries of a number of Dalhousie professors, who in turn were to help in the management and academic life of the college. Students at King's were to have access to all of the amenities Dalhousie, and the academic programs at King's would fold into the College of Arts and Sciences at Dalhousie.[59] Presently, students of both institutions are allowed to switch between the two throughout their enrolment. In spite of the shared academic programs and facilities, the University of King's College maintains its own scholarships, bursaries, athletics programs, and student residences.[60]

Finances

The university completed the 2011–12 year with revenues of $573.597 million and expenses of $536.451 million, yielding a surplus of $37.146 million.[61] The largest source of revenue for the university was provincial operational grants, which made up 32 percent of revenue. Tuition fees generated $123.2 million in the 2011–12 fiscal year, making up 21 percent of revenue. As of 31 March 2012, Dalhousie's endowment was valued at $400.6 million.[61]

Academics

Dalhousie is a publicly funded research university, and a member of the Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada, as well as the U15, a group of Canadian research-intensive universities.[62][63] As of 2011, there were 18,220 students enrolled at the university and 3,700 courses in over 190 degree programs.[64][65] Dalhousie offers more than 3,700 courses and 190 degree programs in twelve undergraduate, graduate, and professional faculties.[66] The requirements for admission differ between students from Nova Scotia, students from other provinces in Canada, and international students due to lack of uniformity in marking schemes. The requirements for admission also differ depending on the program. In 2011, the secondary school average for incoming first-year undergraduate students was 85 percent.[64]

Canadian students may apply for financial aid such as the Nova Scotia Student Assistance Program and Canada Student Loans and Grants through the federal and provincial governments. Financial aid may also be provided in the form of loans, grants, bursaries, scholarships, fellowships, debt reduction, interest relief, and work programs.[67]

Reputation

| University rankings | |

|---|---|

| Global rankings | |

| ARWU World[6] | 201–300 |

| QS World[4] | 283 |

| Times World[5] | 251-300 |

| Canadian rankings | |

| ARWU National[6] | 7–16 |

| QS National[68] | 12 |

| Times National[5] | 12-14 |

| Maclean's Medical/Doctoral[69] | 7 |

The 2015-2016 Times Higher Education World University Rankings placed Dalhousie 201–250th in the world. The 2014 QS World University Rankings ranked the university 235th.[4] According to the 2014 Academic Ranking of World Universities rankings, the university ranked 201–300 in the world and 8–17th in Canada.[70] In terms of national rankings, Maclean's ranked Dalhousie 7th in their 2014 Medical Doctoral university rankings.[69] Dalhousie was ranked in spite of having opted out—along with several other universities in Canada—of participating in Maclean's graduate survey since 2006.[71]

A number of Dalhousie's individual programs and faculties have gained accolades nationally and internationally. In Maclean's 2013 common law school rankings, the Schulich School of Law placed 6th in Canada.[72] In the QS rankings of law programs, the university placed 51–100 in the world.[73] The Rowe School of Business was named the most innovative business school in Canada by European CEO magazine on 17 November 2010.[74]

Research

Dalhousie University is a member of the U15, a group that represents 15 of Canada’s most research-intensive universities. Out of 50 universities in Canada, Research Infosource ranked Dalhousie University the 16th most research-intensive for 2011, with a sponsored research income of $125.147 million, averaging $124,500 per faculty member.[75] In 2003 and 2004, The Scientist placed Dalhousie among the top five places in the world outside the United States for postdoctoral work and conducting scientific research.[76] In 2007 Dalhousie topped the list of The Scientist’s “Best Places to Work in Academia”. The annual list divides research and academic institutions into American and international lists; Dalhousie University ranked first in the international category.[77] According to a survey conducted by The Scientist, Dalhousie was the best non-commercial scientific institute in which to work in Canada.[78]

In terms of research performance, High Impact Universities 2010 ranked Dalhousie 239th out of 500 universities, and 12th in Canada.[79] The university was ranked 194th out of 500 universities and 12th in the country for research performance in the fields of medicine, dentistry, pharmacology, and health sciences.[80] The Higher Education Evaluation and Accreditation Council of Taiwan (HEEACT) ranked Dalhousie 279th in the world and 12th in Canada for its 2011 scientific paper's performances.[81] HEEACT had also ranked Dalhousie 86th in the world and fourth nationally for research performance in geoscience in its 2010 rankings.[82]

Marine research at Dalhousie has become a large focus of the university, with many of the university's faculty members involved in some form of marine research.[83] Notably, Dalhousie is the headquarters of the Ocean Tracking Network, a research effort using implanted acoustic transmitters to study fish migration patterns.[84] Dalhousie houses a number of marine research pools, a wet laboratory, and a benthic flume, which are collectively known as the Aquatron laboratory.[85] Dalhousie is one of the founding members of the Halifax Marine Research Institute, founded on 2 June 2011. The institute, which is a partnership between a number of private industries, government, and post-secondary institutions, was designed to help increase the scale, quality, internationalization and impact of marine research in the region.[86] In 2011, the university, along with WWF-Canada, created the Conservation Legacy For Oceans, which aimed at providing scholarships, funding, curriculum development, and work placements for students and academics dedicated to marine research, law, management, and policy making.[87]

Many of Dalhousie's faculties and departments focus on marine research. The Faculty of Engineering operates the Ocean Research Centre Atlantic, which is dedicated to research and tests in naval and off-shore engineering.[88] Schulich School of Law also operates the Marine & Environmental Law Institute, which carries out research and conducts consultancy activities for governmental and non-governmental organizations.[89] The school's Department of Political Science similarly operates the Centre for Foreign Policy Studies, which is primarily concerned with the fields of Canadian and American foreign, security, and defence policy, including maritime security policy.[90]

Student life

The student body of Dalhousie is currently represented by two student unions; the Dalhousie Student Union, which represents the general student population, and the Dalhousie Association for Graduate Students, which represents the interests of graduate students specifically.[91][92] Dalhousie Student Union began as the Dalhousie Student Government in 1863, and was renamed the University Student Council before taking its present name.[93] The student union recognizes more than 100 student organizations and societies.[94] The organizations and clubs accredited at Dalhousie cover a wide range of interests including academics, culture, religion, social issues, and recreation. Accredited extracurricular organizations at the university fall under the jurisdiction of the Dalhousie Student Union, and must conform to its by-laws.[95] As of 2011, there were three sororities (Omega Pi, Iota Beta Chi, and Alpha Gamma Delta) and three fraternities (Phi Delta Theta, Sigma Chi, and Phi Kappa Pi).[96] They operate as non-accredited organizations and are not recognized by the Dalhousie Student Union.[97]

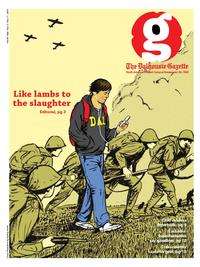

The university's student population operates a number of media outlets. The main student newspaper, The Dalhousie Gazette, claims to be the oldest student-run newspaper in North America.[98] It is published Thursdays, and is distributed to over 100 locations around the Halifax area. The newspaper's offices are in the Student Union building.[98] Dalhousie's student population runs a radio station which began as a radio club in 1964, and began to broadcast and operate as CKDU in 1975; it began FM frequency broadcasting in 1985. CKDU acquired its present frequency 88.1 in 2006 alongside an upgrading of its transmitting power.[99]

Clubs and societies

In addition to the efforts made by the Dalhousie Student Union (DSU) Council,[100] Dalhousie students have created and participated in over 320 clubs/societies.[101] The Management Society, for example, is a group of students in the Faculty of Management who group together to enhance the experience of students in that faculty by hosting events, providing assistance and giving back. Dalhousie offers a website named "Tiger Society" which lists all current clubs and societies that are available for students to join. Through this website, students can request to join a society. Dalhousie also holds a Society Fair at the beginning of each fall and winter semester, in which all societies are given the opportunity to display their purpose/efforts and recruit new members.[102] Student societies partake in a range of activities from simple gatherings, study groups, bake sales, intramural sports teams, to organizing larger scale fundraising events.[103]

Athletics

Dalhousie's sports teams are called the Tigers. The Tigers varsity teams participate in the Atlantic University Sport (AUS) of the Canadian Interuniversity Sport (CIS). There are teams for basketball, hockey, soccer, swimming, track and field, cross country running, and volleyball. The Tigers garnered a number of championships in the first decade of the 20th century, winning 63 AUS championships and 2 CIS championships.[104] More than 2,500 students participate in competitive clubs, intramural sport leagues, and tournaments. Opportunities are offered at multiple skill levels across a variety of sports. Dalhousie has six competitive sports clubs and 17 recreational clubs.[105][106] Dalhousie's Agricultural Campus operates its own varsity team, called the Dalhousie Rams. The Rams varsity team participates in the Atlantic Collegiate Athletic Association, a member of the Canadian Collegiate Athletic Association. The Rams varsity teams include badminton, basketball, rugby, soccer, volleyball, and woodsmen.[107]

Dalhousie has a number of athletic facilities open to varsity teams and students. Dalplex is the largest main fitness and recreational facility. It houses a large fieldhouse, an Olympic-sized swimming pool, an indoor running track, weight rooms, courts and other facilities.[108] Wickwire Field, with a seating capacity of up to 1,200, is the university's main outdoor field and is host to the varsity football, soccer, field hockey, lacrosse and rugby teams.[109] Other sporting facilities include the Studley Gymnasium, and the Sexton Gymnasium and field.[110] The Memorial Arena, home to the varsity hockey team, was demolished in 2012. The school is working to build a new arena jointly with nearby Saint Mary's University, whose facility is also aging.[111] The Agricultural Campus has one athletic facility, the Langille Athletic Centre.[112]

As of 2010, through the efforts of alumni and devoted volunteers, the Dalhousie Football Club was reinstated. Playing in the AFL (Atlantic Football League), the team operates on donations and registration from its players. The team plays its home games at Wickwire Field. Additionally, the university boasts the first quidditch team in Atlantic Canada. As of 2014, the Dalhousie Tigers Quidditch varsity club is the top-ranked team in the area and, though still developing, is showing great promise for regional and national bids in the future.

Insignia and other representations

Seal

The Dalhousie seal is based on the heraldic achievement of the Clan Ramsay of Scotland, of which founder George Ramsay was clan head. The heraldic achievement consists of five parts: shield, coronet, crest, supporters, and motto. One major difference between the Ramsay coat of arms and the university seal is that the Ramsay seal features a griffin and greyhound, and the Dalhousie seal has two dragons supporting the eagle-adorned shield.[113] Initially, the Ramsay coat of arms was used to identify Dalhousie, but the seal has evolved with the amalgamations the university has undergone.[114] The seal was originally silver-coloured, but in 1950, the university's Board of Governors changed it to gold to match the university's colours, gold and black. These colours were adopted in 1887, after the rugby team led the debate about college colours for football jerseys.[115] The shield and eagle of Dalhousie's seal have been used as the logo since 1987, with the present incarnation in use since 2003, which includes the tagline "inspiring minds".[113]

Motto and song

The university motto Ora et Labora translates from Latin as "pray and work"; it adopted in 1870 from the Earl of Dalhousie's motto to replace the university's original one, which the administration believed did not convey confidence.[116] The original motto was Forsan, which tranlsates as Perhaps, and first appeared in the first Dalhousie Gazette of 1869. It was from Virgil's epic poem Aeneid, Book 1, line 203, Forsan et haec olim meminisse iuvabit, which translates as "Perhaps the time may come when these difficulties will be sweet to remember".[115]

A number of songs are commonly played and sung at various events such as commencement, convocation, and athletic contests, including "Carmina Dalhousiana", written in Halifax in 1882. The Dalhousie University songbook was compiled by Charles B. Weikel in 1904.[117]

Notable alumni

Dalhousie graduates have found success in a variety of fields, serving as heads of a diverse array of public and private institutions. Dalhousie University has over 110,000 alumni. Throughout Dalhousie's history, faculty, alumni, and former students have played prominent roles in many fields, and include 89 Rhodes Scholars.[118]

Dalhousie has also educated Nobel laureates. Astrophysicist and Dalhousie alumni Arthur B. McDonald (BSc’64, MSc’65) received the 2015 Nobel Prize in Physics for identifying neutrino change identities and mass.[119] McDonald is one of only four Canadians awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics.[120] McDonald was also previously awarded the Herzberg Prize and the Benjamin Franklin Prize in physics. Other notable graduates of Dalhousie includes Donald O. Hebb, who helped advance the field of neuropsychology,[121] and Kathryn D. Sullivan, the first American woman to walk in space.[122]

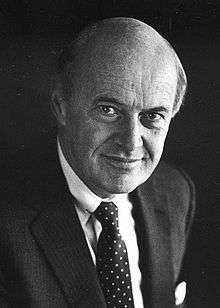

Notable politicians who have graduated from Dalhousie include two Prime Ministers of Canada, R. B. Bennett and Joe Clark.[123][124] Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney attended Dalhousie Law School, though he failed after his first year.[125] Eight graduates have served as Lieutenant Governors: John Crosbie,[126] Myra Freeman,[127] Clarence Gosse,[128] John Keiller MacKay,[129] Henry Poole MacKeen,[127] John Robert Nicholson,[130] Fabian O'Dea,[131] and Albert Walsh.[132] Twelve graduates have served as provincial premiers: Allan Blakeney,[133] John Buchanan,[134] Alex Campbell,[135] Amor De Cosmos,[136] Darrell Dexter,[137] Joe Ghiz,[138] John Hamm,[139] Angus Lewis Macdonald,[140] Russell MacLellan,[141] Gerald Regan,[142][143] Robert Stanfield,[143][144] Clyde Wells,[145] and Danny Williams.[146] The first woman appointed to the Supreme Court of Canada, Bertha Wilson, was a graduate from Dalhousie Law School.[147]

Prominent business leaders who studied at Dalhousie include Jamie Baillie, former CEO of Credit Union Atlantic,[148] Graham Day, former CEO of British Shipbuilders,[149] Sean Durfy, former CEO of WestJet,[150] and Charles Peter McColough, former president and CEO of Xerox.[151]

-

R. B. Bennett, 1st Viscount Bennett, 11th Prime Minister of Canada.

-

Brian Mulroney, 18th Prime Minister of Canada.

-

Edmund Leslie Newcombe, puisne justice of the Supreme Court of Canada.

-

Bertha Wilson, first female puisne justice of the Supreme Court of Canada.

-

Arthur B. McDonald, awarded the Nobel Prize in physics for his work with solar neutrino.

-

Donald O. Hebb, neuropsychologist best known for his cell assembly theory.

-

Kathryn D. Sullivan, first American woman to walk in space.

-

Charles Peter McColough, chairman, CEO, and president of Xerox

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ The British named the colony New Ireland.

References

- ↑ "Dalhousie University Annual Financial Report" (PDF). Dalhousie University. June 2015. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ↑ "18,500 and counting". Ryan Mcnutt. October 31, 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- ↑ "Dalhousie University".

- 1 2 3 "QS World University Rankings - 2016". QS Quacquarelli Symonds Limited. 2016. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 "World University Rankings 2016-2017". Times Higher Education. 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Academic Ranking of World Universities 2016 - Canada". ShanghaiRanking Consultancy. 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ↑ Waite 1997, p. 10.

- 1 2 3 4 "History & Tradition". Dalhousie University. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ↑ Waite 1994, p. 18.

- ↑ Waite 1997, p. 23.

- ↑ Murray 2010, p. 3.

- ↑ Waite 1994, p. 95.

- 1 2 3 4 "Summary and unofficial consolidation of the statutes relating to Dalhousie University" (PDF). Dalhousie University. February 2005. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ↑ Cornwallis Reformed Presbyterian Covenanter Church, Canada's Historic Places Initiative

- ↑ "George Munro Day". Dalhousie University. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ↑ "Maritime Conservatory of Performing Arts". The Canadian Encyclopedia. The Historica Dominion Institute. 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ↑ "History". University of King’s College. 2009. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ↑ "Notes on Engineering and the Origins of the Nova Scotia Technical College". Dalhousie University. 7 October 2005. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ↑ "The Archives of the Technical University of Nova Scotia: A Guide". Dalhousie University. April 2005. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- ↑ "Dalhousie-Technical University Amalgamation Act". Office of the Legislative Counsel, Nova Scotia House of Assembly. 8 June 1998. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ↑ "Dal name hailed in Bible Hill". Chronicle Herald. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- ↑ "Dalhousie, Agricultural College discuss merger". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 20 May 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 "Halifax Campuses". Dalhousie University. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ↑ "About - Agricultural Campus". Dalhousie University. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ↑ "The Buildings of Dalhousie University". Dalhousie University. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ↑ Reeder, Matt (1 December 2015). "A hub to support health care's collaborative future". Dal News.

- 1 2 "Dalhousie College, Original (Grand Parade)". Dalhousie University. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ↑ "Killam Memorial Library". Dalhousie University. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ↑ "W. K. Kellogg Health Science Library". Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ↑ "Sexton Design & Technology Library". Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ↑ "Sir James Dunn Law Library". 10 May 2013.

- ↑ "MacRae Library". Dalhousie University. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ↑ "Dalhousie University Archives". Canadian Heritage Information Network. 2009. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ↑ "McCulloch Museum". Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ↑ "The history of Thomas McCulloch's Life". Dalhousie University. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ↑ "The Permanent Collection". Dalhousie Art Gallery. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- ↑ Schneidereit, Rebecca (6 June 2008). "Contemplating 'Marine Venus'". Dal News. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- ↑ Higgins, Kathleen (2016-03-17). "The Future is Now". The Coast Halifax News. Retrieved 2016-03-27.

- ↑ "Residences-Halifax". Dalhousie University. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ↑ "Howe Hall". Dalhousie University. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ↑ "Residences-Truro". Dalhousie University. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- ↑ "Programs & Activities". Dalhousie University. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ↑ "Student Union Building (SUB)". Dalhousie University. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ↑ "Food & Drink". Dalhousie Student Union. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ↑ "Dalhousie University". AASHE STARS. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ↑ "Climate Change Statement of Action for Canada". 14 May 2015.

- 1 2 "Sustainability at Dalhousie" (PDF). Dalhousie University. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ↑ "College of Sustainability". Dalhousie University.

- ↑ "Office of Sustainability". Dalhousie University.

- ↑ "Dalhousie Student Union Sustainability Office". Dalhousie Student Union.

- ↑ https://divestdal.ca/about/divest-dal/

- ↑ http://www.dal.ca/news/2014/11/26/dal-board-decides-not-to-divest-its-fossil-fuel-endowment-holdin.html

- ↑ https://divestdal.ca/about/timeline-of-divestment/

- ↑ https://divestdal.ca/about/dsu-endorsement/

- ↑ http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/dalhousie-university-senate-fossil-fuels-divestment-1.3491872

- ↑ "2011 - 2012 Membership Senators". Dalhousie University. 13 July 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ↑ "President". Dalhousie University. 18 April 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ↑ "Presidents of Dalhousie". Dalhousie University. 21 October 2009. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- 1 2 3 "History - University of King's College". University of King's College. 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ↑ "King's and Dalhousie - University of King's College". University of King's College. 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- 1 2 "Dalhousie University Annual Financial Report" (PDF). Dalhousie University. June 2012. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ↑ Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada (7 December 2010). "Dalhousie University". Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada.

- ↑ "U15 Submission to the Expert Review Panel on Research and Development" (PDF). Review of Federal Support to R&D. 18 February 2011. Retrieved 22 July 2011.

- 1 2 "Quick Facts & Figures. Dalhousie: by the numbers". Dalhousie University. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- ↑ "Academic Track Record". Dalhousie University. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ↑ "Faculties". Dalhousie University. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ↑ "Student Loans". Dalhousie University. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ↑ "QS World University Rankings® 2016-2017". QS Quacquarelli Symonds Limited. 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- 1 2 "University Rankings 2016: Medical Doctoral". Maclean's. 5 November 2015. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ↑

- ↑ "11 universities bail out of Maclean's survey". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 14 April 2006. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- ↑ "The 2013 Maclean's Law School Rankings". Maclean's. 19 September 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- ↑ "QS World University Rankings by Subject: Law". QS Quacquarelli Symonds Limited. 2011. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ↑ "Faculty of Management named Most Innovative Business School in Canada". Dalhousie University. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ↑ "Canada's Top 50 Research Universities 2011" (PDF). Research Inforsource Inc. 2011. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- ↑ "Dalhousie Research". Archived from the original on 24 June 2009. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- ↑ "Dalhousie University - For academics, Dal's the place to be! - Ranked #1 in The Scientist". Communicationsandmarketing.dal.ca. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ↑ "Dalhousie Communication and Marketing". Communicationsandmarketing.dal.ca. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ↑ "2010 World University Rankings". High Impact Universities. 2010. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- ↑ "2010 Faculty Rankings For Medicine, Dentistry, Pharmacology, and Health Sciences". High Impact Universities. 2010. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- ↑ "Canada". Higher Education Evaluation and Accreditation Council of Taiwan. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- ↑ "Geoscience: Top Universities in Canada". National Taiwan University. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- ↑ "The Value of Marine Research". Dalhousie University. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- ↑ "About the project". Dalhousie University. 8 September 2009. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- ↑ "Aquatron Laboratory". Dalhousie University. 2 July 2009. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- ↑ "Halifax Marine Research Institute launched". Dal News. Dalhousie University. 2 June 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- ↑ "A Conservation Legacy for Oceans". World Wildlife Fund Canada. 2011. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ↑ "About Us". Dalhousie University. 19 February 2008. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- ↑ "Marine & Environmental Law Institute". Dalhousie University. 4 April 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- ↑ "Centre for Foreign Policy Studies". Dalhousie University. 2 May 2012. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ↑ "Who we are and what we do". Dalhousie Student Union. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ↑ "About Us - Dalhousie Association of Graduate Students". Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ↑ "The Archives of Dalhousie Student Union/Student Organizations: A Guide". Dalhousie University. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ↑ "Societies and Organizations". Dalhousie University. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ↑ "The Constitution of the Dalhousie Student Union" (PDF). Dalhousie Student Union. 18 March 2013. p. 21. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ↑ Stokes, Taylor (31 August 2011). "Greek Life". Dalhousie Gazette. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ↑ "Tiger Society - Organizations". Campus Labs. 2013. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- 1 2 "About". Dalhousie Gazette. 4 July 2011. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ↑ "CKDU-FM Society". Campus Labs. 2013. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ↑ "Who We Are and What We Do". Dalhousie University. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- ↑ "Organizations Directory". Dalhousie University. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- ↑ "Society Fair". Dalhousie University. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- ↑ "Societies and Organizations". Dalhousie University. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- ↑ "Varsity Teams". Dalhousie University. 2010. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- ↑ "Intramurals & Clubs at Dal". 2010. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- ↑ "Intramurals at Dal". 2010. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- ↑ "Varsity Teams - Agricultural Campus". Dalhousie Agricultural Campus. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ↑ "Dalplex". 2010. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- ↑ "Wickwire Field". 2010. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- ↑ "Facilities". 2010. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- ↑ Jackson, David (5 February 2013). "Dal, SMU look to province for help in building rink". The Chronicle-Herald. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ↑ "Facilities - Agricultural College". Dalhousie Agricultural Campus. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- 1 2 "Mission & Vision". Dalhousie University. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- ↑ "Traditions and History". Dalhousie University. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- 1 2 Waite 1997, p. 128.

- ↑ Waite 1997, p. 98.

- ↑ Green, Rebecca (2012). "College Songs and Songbooks". The Canadian Encyclopedia. The Historica Foundation of Canada. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- ↑ "Students at Dal". Dalhousie University. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ↑ "The 2015 Nobel Prize in Physics - Press Release". www.nobelprize.org. Retrieved 2015-10-06.

- ↑ "Lists of Nobel Prizes and Laureates". www.nobelprize.org. Retrieved 2015-10-06.

- ↑ "Biographies of Donald Olding Hebb". McGill University. 22 August 2006. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ↑ "Kathryn D. Sullivan (Ph.D.) NASA Astronaut (former)". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. March 2009. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ↑ "Richard Bedford Bennett 1870 - 1947". University of New Brunswick. 20 December 2000. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ↑ "Charles Joseph Clark". Library and Archives Canada. 29 January 2002. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ↑ Sawatsky, J. (1992). Mulroney: the politics of ambition. McClelland & Stewart. p. 106. ISBN 0-7710-7943-5.

- ↑ "John C. Crosbie, PC, OC, ONL, QC". The Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- 1 2 "Past Lieutenant Governors of Nova Scotia". Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ↑ "A Guide to the Clarence Lloyd Gosse fonds". Dalhousie University. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ↑ "The Honourable John Keiller MacKay, PC, DSO, VD, QC (1888–1970)". The Lieutenant Governor of Ontario. 27 April 2010. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ↑ "John Robert Nicholson". Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ↑ "O'Dea, Hon. Fabian (1918-2004)". Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage Web Site Project. 2000. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ↑ "Walsh, Sir Albert Joseph (1900-1958)". Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage Web Site Project. 2000. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ↑ "Former Sask. Premier Allan Blakeney Dies of Cancer". Bell Media Television. 16 April 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ↑ "John Buchanan P.C., Q.C., B. Sc.". 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ↑ "Alexander Bradshaw Campbell". Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ↑ "Amor De Cosmos". Library and Archives Canada. 2 May 2005. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ↑ "Meet Your Premier". Province of Nova Scotia. 2010. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ↑ "Phi Kappa Pi Joe Ghiz Memorial Award". Dalhousie University. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ↑ "Four alumni designated honourary [sic] members of the Executive Council of Nova Scotia". Dalhousie University. 4 March 2010. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ↑ Starr, R. (1988). Richard Hatfield: The Seventeen Year Saga. Formac Publishing Company. p. 10. ISBN 0-88780-153-6.

- ↑ Henderson, T. S. (2007). Angus L. Macdonald: a Provincial Liberal. University of Toronto Press. pp. 20–21. ISBN 0-8020-9459-7.

- ↑ "Russell MacLellan, Q.C.". Wickwire Holm. 2007. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- 1 2 "Gerald Regan's 'amazing' victory". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ↑ Stevens G. (1973). Stanfield. McClelland and Stewart. pp. 30–33.

- ↑ "Newfoundland Biography (1497-2004)". Marianopolis College. 2004. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ↑ "Williams to receive honorary degree". Transcontinental Media. 3 May 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ↑ "The Honourable Madam Justice Bertha Wilson". Supreme Court of Canada. 4 September 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ↑ "Jamie Baillie - Leader of the PC Party". PC Party of Nova Scotia. 2010. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ↑ "Graham Day". Bloomberg Businessweek. 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ↑ "Shakeup at WestJet as CEO Sean Durfy quits". CTVglobemedia. 2010. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ↑ "Xerox boss was from Halifax". The Chronicle Herald. 20 December 2006. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

Bibliography

- Murray, E. M. (2010). A Brief History of Dalhousie University and a Short Story of the Centennial Celebration of the "Little College", September, 1919. Nabu Press. ISBN 1-1762-2434-4.

- Waite, P. (1994). The Lives of Dalhousie University: 1818–1925, Lord Dalhousie's College. McGill-Queen's Press. ISBN 0-7735-6458-6.

- Waite, P. (1997). Lives of Dalhousie University: 1925–1980, The Old College Transformed. McGill-Queen's Press. ISBN 0-7735-1644-1.

External links