Cython

| |

| Developer(s) | Robert Bradshaw, Stefan Behnel, et al. |

|---|---|

| Initial release | 28 July 2007[1] |

| Stable release | 0.24 (4 April 2016) [±][2] |

| Written in | Python, C |

| Operating system | Cross-platform |

| Type | Programming language |

| License | Apache License |

| Website |

cython |

The Cython programming language is a superset of Python, designed to give C-like performance with code which is mostly written in Python.[3][4]

Overview

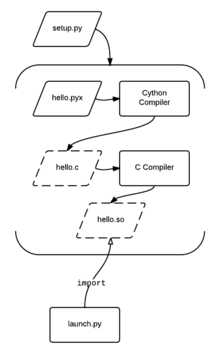

Cython is a compiled language that generates CPython extension modules. These extension modules can then be loaded and used by regular Python code using the import statement. Cython is written in Python and works on Windows, Linux, and Mac OS X, producing source files compatible with CPython 2.4 through 3.5.

It works by producing a standard Python module. However, the behavior differs from standard Python in that the module code, originally written in Python, is translated into C. While the resulting code is fast, it makes many calls into the CPython interpreter and CPython standard libraries to perform actual work. Choosing this arrangement saved considerably on Cython's development time, but modules have a dependency on the Python interpreter and standard library.

Although most of the code is C-based, a small stub loader written in interpreted Python is usually required (unless the goal is to create a loader written entirely in C, which may involve work with the undocumented internals of CPython). However, this is not a major problem due to the presence of the Python interpreter.

Cython has a foreign function interface for invoking C/C++ routines and the ability to declare the static type of subroutine parameters and results, local variables, and class attributes.

Sample program

A sample hello world program for Cython is more complex than in most languages because it interfaces with the Python C API and the setuptools extension building facility. At least three files are required for a basic project:

- A

setup.pyfile to invoke thesetuptoolsbuild process that generates the extension module - A main python program to load the extension module

- Cython source file(s)

The following code listings demonstrate the build and launch process:

# hello.pyx - Python Module, this code will be translated to C by Cython.

def say_hello():

print "Hello World!"

# launch.py - Python stub loader, loads the module that was made by Cython.

# This code is always interpreted, like normal Python.

# It is not compiled to C.

import hello

hello.say_hello()

# setup.py - unnecessary if not redistributing the code, see below

from setuptools import setup

from Cython.Build import cythonize

setup(name = 'Hello world app',

ext_modules = cythonize("*.pyx"))

These commands build and launch the program:

$ python setup.py build_ext --inplace

$ python launch.py

History

Cython is a derivative of the Pyrex language, and supports more features and optimizations than Pyrex.[5][6]

Cython was forked from Pyrex in 2007 by developers of the Sage computer algebra package, because they were unhappy with Pyrex's limitations and could not get patches accepted by Pyrex's maintainer Greg Ewing, who envisioned a much smaller scope for his tool than the Sage developers had in mind. They then forked Pyrex as SageX. When they found people were downloading Sage just to get SageX, and developers of other packages (including Stefan Behnel, who maintains the XML library LXML) were also maintaining forks of Pyrex, SageX was split off the Sage project and merged with cython-lxml to become Cython.[7]

Example

Cython files have a .pyx extension. At its most basic, Cython code looks exactly like Python code. However, whereas standard Python is dynamically typed, in Cython, types can optionally be provided, allowing for improved performance, allowing loops to be converted into C loops where possible. For example:

def primes(int kmax): # The argument will be converted to int or raise a TypeError.

cdef int n, k, i # These variables are declared with C types.

cdef int p[1000] # Another C type

result = [] # A Python type

if kmax > 1000:

kmax = 1000

k = 0

n = 2

while k < kmax:

i = 0

while i < k and n % p[i] != 0:

i = i + 1

if i == k:

p[k] = n

k = k + 1

result.append(n)

n = n + 1

return result

Static type declarations and performance

A Cython program that implements the same algorithm as a corresponding Python program may consume fewer computing resources such as core memory and processing cycles due to differences between the CPython and Cython execution models. A basic Python program is loaded and executed by the CPython virtual machine, so both the runtime and the program itself consume computing resources. A Cython program is compiled to C code, which is further compiled to machine code, so the virtual machine is used only briefly when the program is loaded.[8][9][10][11]

Cython employs:

- Optimistic optimizations

- Type inference (optional)

- Low overhead in control structures

- Low function call overhead[12][13]

Performance depends both on what C code is generated by Cython and how that code is compiled by the C compiler.[14]

Uses

Cython is particularly popular among scientific users of Python,[10][15][16] where it has "the perfect audience" according to Python developer Guido van Rossum.[17] Of particular note:

- The free software SageMath computer algebra system depends on Cython, both for performance and to interface with other libraries.[18]

- Significant parts of the scientific computing libraries SciPy, pandas and scikit-learn are written in Cython.[19][20]

- Some high traffic websites such as Quora use Cython.[21]

Cython's domain is not limited to just numerical computing. For example, the lxml XML toolkit is written mostly in Cython, and like its predecessor Pyrex, Cython is used to provide Python bindings for many C and C++ libraries like the messaging library ZeroMQ.[22] Cython can also be used to develop parallel programs for multi-core processor machines; this feature makes use of the OpenMP library.

See also

References

- ↑ Dr. Behnel, Stefan (2008). "The Cython Compiler for C-Extensions in Python". EuroPython (28 July 2007: official Cython launch). Vilnius/Lietuva.

- ↑ "Cython: C-Extensions for Python".

- ↑ "Cython - an overview — Cython 0.19.1 documentation". Docs.cython.org. Retrieved 2013-07-21.

- ↑ Smith, Kurt (2015). Cython: A Guide for Python Programmers. O'Reilly Media. ISBN 978-1-4919-0155-7.

- ↑ "Differences between Cython and Pyrex".

- ↑ Ewing, Greg (21 March 2011). "Re: VM and Language summit info for those not at Pycon (and those that are!)" (Message to the electronic mailing-list python-dev). Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ↑ Says Sage and Cython developer Robert Bradshaw at the Sage Days 29 conference (22 March 2011). "Cython: Past, Present and Future". youtube.com. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ↑ Oliphant, Travis (2011-06-20). "Technical Discovery: Speeding up Python (NumPy, Cython, and Weave)". Technicaldiscovery.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2013-07-21.

- ↑ Behnel, Stefan; Bradshaw, Robert; Citro, Craig; Dalcin, Lisandro; Seljebotn, Dag Sverre; Smith, Kurt (2011). "Cython: The Best of Both Worlds". Computing in Science and Engineering. 13 (2): 31–39. doi:10.1109/MCSE.2010.118.

- 1 2 Seljebot, Dag Sverre (2009). "Fast numerical computations with Cython". Proceedings of the 8th Python in Science Conference (SciPy 2009): 15–22.

- ↑ Wilbers, I.; Langtangen, H. P.; Ødegård, Å. (2009). B. Skallerud; H. I. Andersson, ed. "Using Cython to Speed up Numerical Python Programs" (PDF). Proceedings of MekIT'09: 495–512. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- ↑ "wrapper benchmarks for several Python wrapper generators (except Cython)".

- ↑ "wrapper benchmarks for Cython, Boost.Python and PyBindGen".

- ↑ "Cython: C-Extensions for Python". Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ↑ "inSCIght: The Scientific Computing Podcast" (Episode 6).

- ↑ Millman, Jarrod; Aivazis, Michael (2011). "Python for Scientists and Engineers". Computing in Science and Engineering. 13 (2): 9–12. doi:10.1109/MCSE.2011.36.

- ↑ Who also criticizes Cython (21 March 2011). "Re: VM and Language summit info for those not at Pycon (and those that are!)" (Message to the electronic mailing-list python-dev). Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ↑ Erocal, Burcin; Stein, William (2010). "The Sage Project: Unifying Free Mathematical Software to Create a Viable Alternative to Magma, Maple, Mathematica and MATLAB" (PDF). Mathematical Software‚ ICMS 2010. Springer Berlin / Heidelberg. 6327: 12–27. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-15582-6_4.

- ↑ "SciPy 0.7.2 release notes".

- ↑ Pedregosa, Fabian; Varoquaux, Gaël; Gramfort, Alexandre; Michel, Vincent; Thirion, Bertrand; Grisel, Olivier; Blondel, Mathieu; Prettenhofer, Peter; Weiss, Ron; Dubourg, Vincent; Vanderplas, Jake; Passos, Alexandre; Cournapeau, David (2011). "Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python". Journal of Machine Learning Research. 12: 2825–2830.

- ↑ "Is Quora still running on PyPy?".

- ↑ "ØMQ: Python binding".