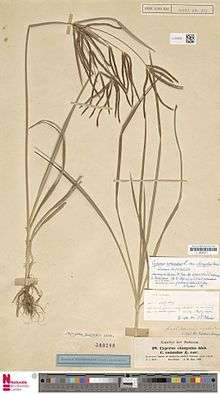

Cyperus rotundus

| Cyperus rotundus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Monocots |

| (unranked): | Commelinids |

| Order: | Poales |

| Family: | Cyperaceae |

| Genus: | Cyperus |

| Species: | C. rotundus |

| Binomial name | |

| Cyperus rotundus L. | |

Cyperus rotundus (coco-grass,[1] Java grass,[1] nut grass,[1] purple nut sedge[1] or purple nutsedge,[2] red nut sedge,[1] Khmer kravanh chruk[3]) is a species of sedge (Cyperaceae) native to Africa, southern and central Europe (north to France and Austria), and southern Asia. The word cyperus derives from the Greek κύπερος, kyperos,[4] and rotundus is from Latin, meaning "round".[5] The earliest attested form of the word cyperus is the Mycenaean Greek 𐀓𐀞𐀫, ku-pa-ro, written in Linear B syllabic script.[6]

Cyperus rotundus is a perennial plant, that may reach a height of up to 140 cm (55 inches). The names "nut grass" and "nut sedge" – shared with the related species Cyperus esculentus – are derived from its tubers, that somewhat resemble nuts, although botanically they have nothing to do with nuts.

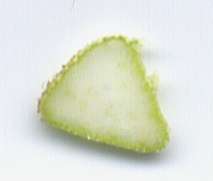

As in other Cyperaceae, the leaves sprout in ranks of three from the base of the plant, around 5–20 cm long. The flower stems have a triangular cross-section. The flower is bisexual and has three stamina and a three-stigma carpel, with the flower head having 3–8 unequal rays. The fruit is a three-angled achene.

The root system of a young plant initially forms white, fleshy rhizomes, up to 25 mm in dimension, in chains. Some rhizomes grow upward in the soil, then form a bulb-like structure from which new shoots and roots grow, and from the new roots, new rhizomes grow. Other rhizomes grow horizontally or downward, and form dark reddish-brown tubers or chains of tubers.

It prefers dry conditions, but will tolerate moist soils, and often grows in wastelands and in crop fields.[3]

History

C. rotundus was part of a set of starchy tuberous sedges that may have been eaten by Pliocene hominins. It was a staple of Aboriginal populations in Central Australia.[7]

Biomarkers and microscopic evidence of C. rotundus are present in human dental calculus found at the Al Khiday archaeological complex in central Sudan dating from before 6700 BCE to the Meroitic pre-Islamic Kingdom of 300–400 CE. It is suggested that C. rotundus consumption may have contributed to the relatively low frequency of dental caries among the Meroitic population of Al Khiday because of its ability to inhibit Streptococcus mutans.[7]

C. rotundus was employed in ancient Egypt, Mycenean Greece, and elsewhere as an aromatic and to purify water. It was used by ancient Greek physicians Theophrastus, Pliny the Elder, and Dioscorides as both medicine and perfume.[7]

Uses

C. rotundus has many beneficial uses. It is a staple carbohydrate in tropical regions for recent hunter-gatherers and is a famine food in some agrarian cultures.

Folk medicine

In traditional Chinese medicine it is considered the primary qi-regulating herb.

The plant is mentioned in the ancient Indian ayurvedic medicine Charaka Samhita (circa 100 AD). Modern ayurvedic medicine uses the plant, known as musta or musta moola churna,[8][9] for treating fevers, digestive system disorders, dysmenorrhea and other maladies.

Arabs of the Levant traditionally use roasted tubers, while they are still hot, or hot ashes from burned tubers, to treat wounds, bruises, carbuncles, etc. Western and Islamic herbalists including Dioscorides, Galen, Serapion, Paulus Aegineta, Avicenna, Rhazes, and Charles Alston have described medical uses as stomachic, emmenagogue, and deobstruent, and in emollient plasters.[10][11]

The antibacterial properties of the tubers may have helped prevent tooth decay in people who lived in Sudan 2000 years ago. Less than 1% of that local population's teeth had cavities, abscesses, or other signs of tooth decay, though those people were probably farmers (early farmers' teeth typically had more tooth decay than those of hunter-gatherers because the high grain content in their diet created a hospitable environment for bacteria that flourish in the human mouth, excreting acids that eat away at the teeth).[12][13]

Modern uses and studies

Several pharmacologically active substances have been identified in C. rotundus: α-cyperone, β-selinene, cyperene, patchoulenone, sugeonol, kobusone, and isokobusone, that may scientifically explain the folk- and alternative-medicine uses. A sesquiterpene, rotundone, so called because it was originally extracted from the tuber of this plant, is responsible for the spicy aroma of black pepper and the peppery taste of certain Australian Shiraz wines.[14]

Anti-microbial, anti-malarial, anti-oxidant, and anti-diabetic compounds have been isolated and identified from C. rotundus.[7]

Food

Despite the bitter taste of the tubers, they are edible and have nutritional value. Some part of the plant was eaten by humans at some point in ancient history.[15] The plant is known to have a high amount of carbohydrates.[16] The plant is known to have been eaten in Africa in famine-stricken areas.

In addition, the tubers are an important nutritional source of minerals and trace elements for migrating birds such as cranes.

Sleeping mats

The well dried coco grass is used as mats for sleeping.

Invasive problems and eradication

Cyperus rotundus is one of the most invasive weeds known, having spread out to a worldwide distribution in tropical and temperate regions. It has been called "the world's worst weed"[17] as it is known as a weed in over 90 countries, and infests over 50 crops worldwide. In the United States it occurs from Florida north to New York and Minnesota and west to California and most of the states in between. In the uplands of Cambodia, it is described as an important agricultural weed.[3]

Its existence in a field significantly reduces crop yield, both because it is a tough competitor for ground resources, and because it is allelopathic, the roots releasing substances harmful to other plants. Similarly, it also has a bad effect on ornamental gardening. The difficulty to control it is a result of its intensive system of underground tubers, and its resistance to most herbicides. It is also one of the few weeds that cannot be stopped with plastic mulch. See picture.

Weed pulling in gardens usually results in breakage of roots, leaving tubers in the ground from which new plants emerge quickly. Ploughing distributes the tubers in the field, worsening the infestation; even if the plough cuts up the tubers to pieces, new plants can still grow from them. In addition, the tubers can survive harsh conditions, further contributing to the difficulty to eradicate the plant. Hoeing in traditional agriculture of South East Asia does not remove the plant but leads to rapid regrowth.[3]

Most herbicides may kill the plant's leaves, but most have no effect on the root system and the tubers. Glyphosate will kill some of the tubers (along with most other plants) and repeated application can be successful. Halosulfuron-methyl[18] will control nut grass after repeated applications without damaging lawns.[19] The plant does not tolerate shading and 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) slows its growth in pastures and mulch crops.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Germplasm Resources Information Network: Cyperus rotundus".

- ↑ "BSBI List 2007". Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland. Archived from the original (xls) on 2015-02-25. Retrieved 2014-10-17.

- 1 2 3 4 MARTIN, Robert & POL Chanthy, 2009, Weeds of Upland Cambodia, ACIAR Monagraph 141, Canberra,

- ↑ κύπερος. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ↑ rotundus. Charlton T. Lewis and Charles Short. A Latin Dictionary on Perseus Project.

- ↑ "The Linear B word ku-pa-ro". Palaeolexicon. Word study tool of ancient languages.

- 1 2 3 4 Buckley S, Usai D, Jakob T, Radini A, Hardy K (2014) Dental Calculus Reveals Unique Insights into Food Items, Cooking and Plant Processing in Prehistoric Central Sudan. PLoS ONE 9(7): e100808. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0100808 http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0100808

- ↑ "Effect of polyherbal formulation on experimental models of inflammatory bowel diseases". J Ethnopharmacol. 90 (2-3): 195–204. February 2004. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2003.09.042. PMID 15013181.

- ↑ Manish V. Patel; et al. (October 2010). "Effects of Ayurvedic treatment on forty-three patients of ulcerative colitis". Ayu. 31 (4): 478–481. doi:10.4103/0974-8520.82046. PMC 3202252

. PMID 22048543.

. PMID 22048543. - ↑ Aegineta Paulus (translation and commentary by Francis Adams) (1847). The seven books of Paulus Aegineta: Translated from the Greek.

- ↑ Charles Alston (1770). Lectures on the materia medica: containing the natural history of drugs.

- ↑ Watson, Traci (July 16, 2014). "Ancient People Achieved Remarkably Clean Teeth With Noxious Weed". National Geographic. Retrieved 2014-07-19.

- ↑ Feltman, Rachel (July 17, 2014). "Pesky weed may have helped prehistoric humans fight cavities, report says". Washington Post. p. A3. from journal PLOS One

- ↑ Determination of Rotundone, the Pepper Aroma Impact Compound, in Grapes and Wine. Tracey E. Siebert, Claudia Wood, Gordon M. Elsey and Alan P. Pollnitz. J. Agric. Food Chem., 2008, 56 (10), pp 3745–3748. URL: http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/jf800184t. Accessed 9/10/2012.

- ↑ "The Archaeology News Network: Tooth plaque provides unique insights into our prehistoric ancestors' diet". archaeologynewsnetwork.blogspot.com.

- ↑ "Tooth plaque provides unique insights into our prehistoric ancestors' diet". ScienceDaily.

- ↑ Holm, LeRoy G.; Plucknett, Donald L..; et al. (1977). The World's worst weeds: Distribution and biology. Hawaii: University Press of Hawaii.

- ↑ USDOE-Bonneville Power Administration, Halosulfron-methyl Herbicide Fact Sheet, March 2000

- ↑ Nutgrass – a tough little nut to crack, January 2016

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cyperus rotundus. |

- Flora Europaea: Cyperus rotundus

- USDA Plants Profile: Cyperus rotundus

- USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service: Cyperus rotundus (pdf file)

- Use in Chinese and Ayurvedic medicine

- A Tel-Aviv University study mentioning its nutritional importance for migrating birds (in Hebrew)

- Caldecott, Todd (2006). Ayurveda: The Divine Science of Life. Elsevier/Mosby. ISBN 0-7234-3410-7. Contains a detailed monograph on Cyperus rotundus (Musta; Mustaka) as well as a discussion of health benefits and usage in clinical practice. Available online at http://www.toddcaldecott.com/index.php/herbs/learning-herbs/310-musta