Current account

In economics, a country's current account is one of the two components of its balance of payments, the other being the capital account (sometimes called the financial account). The current account consists of the balance of trade, net primary income or factor income (earnings on foreign investments minus payments made to foreign investors) and net cash transfers, that have taken place over a given period of time. The current account balance is one of two major measures of a country's foreign trade (the other being the net capital outflow). A current account surplus indicates that the value of a country's net foreign assets (i.e. assets less liabilities) grew over the period in question, and a current account deficit indicates that it shrank. Both government and private payments are included in the calculation. It is called the current account because goods and services are generally consumed in the current period.[1][2]

Overview

The current account is an important indicator about an economy's health. It is defined as the sum of the balance of trade (goods and services exports less imports), net income from abroad and net current transfers. A positive current account balance indicates that the nation is a net lender to the rest of the world, while a negative current account balance indicates that it is a net borrower from the rest of the world. A current account surplus increases a nation’s net foreign assets by the amount of the surplus, and a current account deficit decreases it by that amount.

A country's balance of trade is the net or difference between the country's exports of goods and services and its imports of goods and services, ignoring all financial transfers, investments and other components, over a given period of time. A country is said to have a trade surplus if its exports exceed its imports, and a trade deficit if its imports exceed its exports.

Positive net sales abroad generally contributes to a current account surplus; negative net sales abroad generally contributes to a current account deficit. Because exports generate positive net sales, and because the trade balance is typically the largest component of the current account, a current account surplus is usually associated with positive net exports.

In the net factor income or income account, income payments are outflows, and income receipts are inflows. Income are receipts from investments made abroad (note: investments are recorded in the capital account but income from investments is recorded in the current account) and money sent by individuals working abroad, known as remittances, to their families back home. If the income account is negative, the country is paying more than it is taking in interest, dividends, etc.

The various subcategories in the income account are linked to specific respective subcategories in the capital account, as income is often composed of factor payments from the ownership of capital (assets) or the negative capital (debts) abroad. From the capital account, economists and central banks determine implied rates of return on the different types of capital. The United States, for example, gleans a substantially larger rate of return from foreign capital than foreigners do from owning United States capital.

In the traditional accounting of balance of payments, the current account equals the change in net foreign assets. A current account deficit implies a paralleled reduction of the net foreign assets.

- Current account = changes in net foreign assets.

If an economy is running a current account deficit, it is absorbing (absorption = domestic consumption + investment + government spending) more than that it is producing. This can only happen if some other economies are lending their savings to it (in the form of debt to or direct/ portfolio investment in the economy) or the economy is running down its foreign assets such as official foreign currency reserve.

On the other hand, if an economy is running a current account surplus it is absorbing less than that it is producing. This means it is saving. As the economy is open, this saving is being invested abroad and thus foreign assets are being created.

Calculation

Normally, the current account is calculated by adding up the 4 components of current account: goods, services, income and current transfers.[3]

- Goods

- Being movable and physical in nature, goods are often traded by countries all over the world. When a transaction of certain good's ownership from a local country to a foreign country takes place, this is called an "export." The other way around, when a good's owner changes to a local inhabitant from a foreigner, is defined to be an "import." In calculating current account, exports are marked as credit (the inflow of money) and imports as debit. (the outflow of money.)

- Services

- When an intangible service (e.g. tourism) is used by a foreigner in a local land and the local resident receives the money from a foreigner, this is also counted as an export, thus a credit.

- Income

- A credit of income happens when an individual or a company of domestic nationality receives money from a company or individual with foreign identity. A foreign company's investment upon a domestic company or a local government is considered as a debit.

- Current transfers

- Current transfers take place when a certain foreign country simply provides currency to another country with nothing received as a return. Typically, such transfers are done in the form of donations, aids, or official assistance.

A country's current account can be calculated by the following formula:

Where CA is the current account, X and M are respectively the export and import of goods and services, NY the net income from abroad, and NCT the net current transfers.

Reducing current account deficits

A nation’s current account balance is influenced by numerous factors – its trade policies, exchange rate, competitiveness, forex reserves, inflation rate and others. Since the trade balance (exports minus imports) is generally the biggest determinant of the current account surplus or deficit, the current account balance often displays a cyclical trend. During a strong economic expansion, import volumes typically surge; if exports are unable to grow at the same rate, the current account deficit will widen. Conversely, during a recession, the current account deficit will shrink if imports decline and exports increase to stronger economies. The currency exchange rate exerts a significant influence on the trade balance, and by extension, on the current account. An overvalued currency makes imports cheaper and exports less competitive, thereby widening the current account deficit (or narrowing the surplus). An undervalued currency, on the other hand, boosts exports and makes imports more expensive, thus increasing the current account surplus (or narrowing the deficit). Nations with chronic current account deficits often come under increased investor scrutiny during periods of heightened uncertainty. The currencies of such nations often come under speculative attack during such times. This creates a vicious circle where precious foreign exchange reserves are depleted to support the domestic currency, and this forex reserve depletion - combined with a deteriorating trade balance - puts further pressure on the currency. Embattled nations are often forced to take stringent measures to support the currency, such as raising interest rates and curbing currency outflows.

Action to reduce a substantial current account deficit usually involves increasing exports (goods going out of a country and entering abroad countries) or decreasing imports (goods coming from a foreign country into a country). Firstly, this is generally accomplished directly through import restrictions, quotas, or duties (though these may indirectly limit exports as well), or by promoting exports (through subsidies, custom duty exemptions etc.). Influencing the exchange rate to make exports cheaper for foreign buyers will indirectly increase the balance of payments. Also, Currency wars, a phenomenon evident in post recessionary markets is a protectionist policy, whereby countries devalue their currencies to ensure export competitiveness. Secondly, adjusting government spending to favor domestic suppliers is also effective.

Less obvious methods to reduce a current account deficit include measures that increase domestic savings (or reduced domestic borrowing), including a reduction in borrowing by the national government.

A current account deficit is not always a problem. The Pitchford thesis states that a current account deficit does not matter if it is driven by the private sector. It is also known as the "consenting adults" view of the current account, as it holds that deficits are not a problem if they result from private sector agents engaging in mutually beneficial trade. A current account deficit creates an obligation of repayments of foreign capital, and that capital consists of many individual transactions. Pitchford asserts that since each of these transactions were individually considered financially sound when they were made, their aggregate effect (the current account deficit) is also sound.

A deficit implies we import more goods and services than we export.

To be more precise, the current account equals: Trade in goods (visible balance) Trade in services (Invisible Balance) e.g. insurance and services Investment incomes e.g. dividends, interest and migrants remittances from abroad Net transfers – e.g. International aid The current account is essentially exports – imports (+net international investment balance)

It is also worth noting that if we have a current account deficit, in a floating exchange rate this must be balanced by a surplus on the financial / capital account.

Interrelationships in the balance of payments

The balance of payments (BOP) is the place where countries record their monetary transactions with the rest of the world. Transactions are either marked as a credit or a debit. Within the BOP there are three separate categories under which different transactions are categorized: the current account, the capital account and the financial account. In the current account, goods, services, income and current transfers are recorded. In the capital account, physical assets such as a building or a factory are recorded. And in the financial account, assets pertaining to international monetary flows of, for example, business or portfolio investments are noted.

Absent changes in official reserves, the current account is the mirror image of the sum of the capital and financial accounts. One might then ask: Is the current account driven by the capital and financial accounts or is it vice versa? The traditional response is that the current account is the main causal factor, with capital and financial accounts simply reflecting financing of a deficit or investment of funds arising as a result of a surplus. However, more recently some observers have suggested that the opposite causal relationship may be important in some cases. In particular, it has controversially been suggested that the United States current account deficit is driven by the desire of international investors to acquire U.S. assets (See Ben Bernanke,[4] William Poole links below). However, the main viewpoint undoubtedly remains that the causative factor is the current account and that the positive financial account reflects the need to finance the country's current account deficit.

Current account surpluses are facing current account deficits of other countries, the indebtedness of which towards abroad therefore increases. According to Balances Mechanics by Wolfgang Stützel this is described as surplus of expenses over the revenues. Increasing imbalances in foreign trade are critically discussed as a possible cause of the financial crisis since 2007.[5] Many keynesian economists consider the existing differences between the current accounts in the eurozone to be the root cause of the Euro crisis, for instance Yanis Varoufakis, Heiner Flassbeck,[6] Paul Krugman[7] or Joseph Stiglitz.[8]

U.S. account deficits

Since 1989, the current account deficit of the US has been increasingly large, reaching close to 7% of the GDP in 2006. In 2011, it was the highest deficit in the world.[9] New evidence, however, suggests that the U.S. current account deficits are being mitigated by positive valuation effects.[10] That is, the U.S. assets overseas are gaining in value relative to the domestic assets held by foreign investors. The net foreign assets of the U.S. are therefore not deteriorating one to one with the current account deficits. The most recent experience has reversed this positive valuation effect, however, with the US net foreign asset position deteriorating by more than two trillion dollars in 2008, down to less than $18 trillion, but has since risen to $25 trillion.[11] This temporary decline was due primarily to the relative under-performance of domestic ownership of foreign assets (largely foreign equities) compared to foreign ownership of domestic assets (largely US treasuries and bonds).

OECD Quarterly International Trade Statistics

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, OECD — an international economic organisation of 34 countries, founded in 1961 to "promote policies that will improve the economic and social well-being of people around the world"[12] — produces quarterly reports on its 34 member nations comparing statistics on balance of payments and international trade in terms of current account balance in billions of US dollars and as a percentage of GDP.[13]

For example, according to their report the current account balance in billions of US dollars of several countries can be compared,

- Australia for the year 2013 was -51.39 and the year 2014 was -43.69, with each quarter between 2013 Q1 through 2015 Q2 ranging from a low of -14.81 in Q2 2015 to a high of -8.53 in Q1 2014. Australia's current account balance in Q2 2015 was up down to -14.81. The current balance in Q2 as a percentage of GDP was -4.7%.

- Canada for the year 2013 was -54.62, and year 2014 was -37.46 with each quarter between 2013 Q1 through 2015 Q2 ranging from a low of -14.63 in Q1 2015 to a high of -8.28 in Q3 2014. Canada's current account balance in Q2 2015 was up at -14.15. The current balance in Q2 as a percentage of GDP was -3.5%.

- China for the year 2013 was 148.33, and year 2014 was 219.90 with each quarter between 2013 Q1 through 2015 Q2 ranging from a low of 31.96 in Q4 2014 to a high of 75.58 in Q4 2013. The United State's current account balance in Q2 2015 was down to 73.03. The current balance in 2013 as a percentage of GDP was 1.6%.

- Germany for the year 2013 was 238.61, and year 2014 was 285.82 with each quarter between 2013 Q1 through 2015 Q2 ranging from a low of 54.13 in Q3 2013 to a high of 68.89 in Q1 2014. Germany's current account balance in Q2 2015 was up to 68.39. The current balance in Q2 as a percentage of GDP was 8.2%.

- Greece for the year 2013 was -4.89, and year 2014 was -5.00 with each quarter between 2013 Q1 through 2015 Q2 ranging from a low of -2.76 in Q1 2013 to a high of 0.01 in Q2 2015. Greece's current account balance in Q2 2015 was up to 0.01. The current balance in Q2 as a percentage of GDP was 0.0.

- The United States for the year 2013 was -376.76, and year 2014 was -389.53 with each quarter between 2013 Q1 through 2015 Q2 ranging from a low of -118.30 in Q1 2013 to a high of -81.63 in Q4 2013. The United State's current account balance in Q2 2015 was up to -109.68. The current balance in Q2 as a percentage of GDP was -2.4%.

The report also compares countries on services balance, exports of services, import of services, goods balance, export of goods and imports of goods in billions of US dollars.[13]

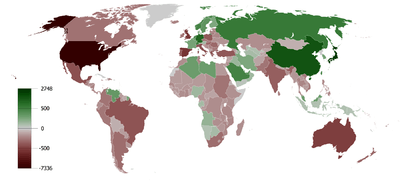

The World Factbook

The World Factbook,[14] a reference resource produced by the Central Intelligence Agency that collects data and publishes online open reports comparing the current account balance of countries.[15] According to The World Factbook, "[c]urrent account balance compares a country's net trade in goods and services, plus net earnings, and net transfer payments to and from the rest of the world during the period specified. These figures are calculated on an exchange rate basis."[15] The top ten on their list of countries by current account balance in 2014 were Germany #1 with $286,400,000,000, China #2 with $219,700,000,000, Netherlands #3 with $90,160,000,000, South Korea #4 with $89,220,000,000, Saudi Arabia #5 with $76,920,000,000, Taiwan #6 with $65,420,000,000, Russia #7 with $59,460,000,000, Singapore #8 with $58,770,000,000, Qatar #9 with $54,840,000,000 and the United Arab Emirates #10 with $54,630,000,000.[15]

On the same list the bottom ten countries by current account balance in 2014 were Mexico #185 at -$24,980,000,000, Indonesia #186 at -$26,230,000,000, France #187 at -$26,240,000,000, India #188 at -$27,530,000,000, European Union #189 at -$34,490,000,000 (2011 est), Canada #190 -$37,500,000,000, Australia #191 at -$43,750,000,000, Turkey #192 at -$46,530,000,000, Brazil #193 at -$103,600,000,000, United Kingdom #194 at -$173,900,000,000, United States #195 at -$389,500,000,000.[15]

International Monetary Fund

According to a 2012 article published by the International Monetary Fund[2] the authors argue that a current account deficit with higher investments and lower savings may indicate that the economy of a country is highly productive and growing. If there is an excess of imports over exports there may be problems in terms of competitiveness. Low savings and high investment can also be caused by a "reckless fiscal policy or a consumption binge."[2] China's financial system favors the accumulation of large surpluses while the United States carries "large and persistent current account deficits" which has created a trade imbalance.[2]

The authors note that,[2]

"Moreover, in practice, private capital often flows from developing to advanced economies. The advanced economies, such as the United States ... run current account deficits, whereas developing countries and emerging market economies often run surpluses or near surpluses. Very poor countries typically run large current account deficits, in proportion to their gross domestic product (GDP), that are financed by official grants and loans."— Ghosh and Ramakrishnan, IMF, 2012

See also

- Balance of payments

- Balance of trade

- List of countries by current account balance

- Global saving glut

- FRED (Federal Reserve Economic Data)

- U.S. public debt

References

- ↑ Ecological Economics: Principles And Applications; Herman E. Daly, Joshua Farley; Island Press, 2003

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ghosh, Atish; Ramakrishnan, Uma (28 March 2012). "Current Account Deficits: Is There a Problem?". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- ↑ shyam (18 August 2009). "Understanding The Current Account In The Balance Of Payments".

- ↑ The Global Saving Glut and the U.S. Current Account Deficit http://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/speeches/2005/200503102/

- ↑ Wolfgang Münchau, „Kernschmelze im Finanzsystem", Carl Hanser Verlag, München, 2008, S. 155ff.; vgl. Benedikt Fehr: „'Bretton Woods II ist tot. Es lebe Bretton Woods III'" in FAZ 12. Mai 2009, S. 32. FAZ.Net, Stephanie Schoenwald:„Globale Ungleichgewichte. Sind sie für die Finanzmarktkrise (mit-) verantwortlich?" KfW (Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau) Research. MakroScope. No. 29, Februar 2009. S. 1.

Zu den außenwirtschaftlichen Ungleichgewichten als „makroökonomischer Nährboden" der Krise siehe auch Deutsche Bundesbank: Finanzstabilitätsbericht 2009, Frankfurt am Main, November 2009 (PDF)., Gustav Horn, Heike Joebges, Rudolf Zwiener: „Von der Finanzkrise zur Weltwirtschaftskrise (II), Globale Ungleichgewichte: Ursache der Krise und Auswegstrategien für Deutschland" IMK-Report Nr. 40, August 2009, S. 6 f. (PDF; 260 kB) - ↑ Heiner Flassbeck: Wege aus der Eurokrise. YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mfKuosvO6Ac

- ↑ Paul Krugman Blog: Germans and Aliens, available on line at: http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/01/09/germans-and-aliens/

- ↑ Joseph Stiglitz: Is Mercantilism Doomed to Fail?, Online verfügbar unter https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D207fSLnxHk

- ↑ https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2187rank.html

- ↑ Current Account Sustainability and Relative Reliability https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2187rank.html

- ↑

- ↑ "About". OECD. nd. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- 1 2 Periodical Quarterly Statistics of International Trade: Trends and Indicators. OECD (Report). 2015. ISSN 2313-0857. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- ↑ Central Intelligence Agency (2008-01-03). "Where in the World is Mt. Kilimanjaro? Visit the CIA World Factbook to Find Out". Retrieved 2008-01-04.

- 1 2 3 4 "Country Comparison: Current Account Balance". CIA. 2015. ISSN 1553-8133. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

Further reading

- Carrasco, C. A., & Peinado, P. (2014). On the origin of European imbalances in the context of European integration, Working papers wpaper71, Financialisation, Economy, Society & Sustainable Development (FESSUD) Project.

External links

- Are Trade Deficits a Drag on U.S. Economic Growth?

- Ellen Frank, Where Do U.S.A Dollars Go When the United States Runs a Trade Deficit? from Dollars & Sense magazine, March/April 2004.

- CIA Fact Book of Account Rankings Worldwide

- Current Account Surplus Watch from New America Foundation

- The Global Saving Glut and the U.S. Current Account Deficit from Global saving glut