Cultural depictions of turtles

Turtles are frequently depicted in popular culture as easygoing, patient, and wise creatures. Due to their long lifespan, slow movement, sturdiness, and wrinkled appearance, they are an emblem of longevity and stability in many cultures around the world.[1][2] Turtles are regularly incorporated into human culture, with painters, photographers, poets, songwriters, and sculptors using them as subjects.[3] They have an important role in mythologies around the world,[4] and are often implicated in creation myths regarding the origin of the Earth.[5] Sea turtles are a charismatic megafauna and are used as symbols of the marine environment and environmentalism.[3]

As a result of its role as a slow, peaceful creature in culture, the turtle can be misconceived as a sedentary animal; however, many types of turtle, especially sea turtles, frequently migrate over large distances in oceans.[6]

In mythology, legends, and folklore

The tortoise is a symbol of wisdom and knowledge, and is able to defend itself on its own. It personifies water, the moon, the Earth, time, immortality, and fertility. Creation is associated with the tortoise and it is also believed that the tortoise bears the burden of the whole world.[7]

The turtle has a prominent position as a symbol of steadfastness and tranquility in religion, mythology, and folklore from around the world.[6] A tortoise's longevity is suggested by its long lifespan and its shell, which was thought to protect it from any foe.[2] In the cosmological myths of several cultures a World Turtle carries the world upon its back or supports the heavens.[5] The mytheme of a World Tortoise, along with that of a world-bearing elephant, was discussed comparatively by Edward Burnett Tylor (1878:341).

Turtles were presented in rock art.[8]

For alchemists, the tortoise symbolizes chaos, or massa confusa.[7]

Africa

In African fairy tales, the tortoise is the most clever animal.[7]

Mzee (Swahili for "wise old man") is the name of a 130-year-old Aldabra tortoise.

In the southern part of Africa, storytales about a tortoise named Fudukazi are common. Fudukazi gave the animals their color.

Nigeria

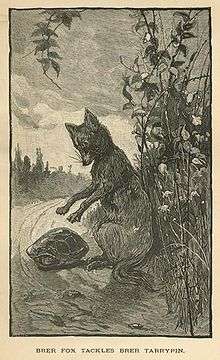

Ijapa the tortoise (alternatively called Alabahun) is a trickster, accomplishing heroic deeds or getting into trouble in a cycle of tales told by the Yoruba of Nigeria and Benin Republic (West Africa).[5]

Ancient Egypt

Turtle "Shetyw", "Shetw", "Sheta", "shtyw" was common in Ancient Egyptian Art (especially Predynastic and Old Kingdom art).[9] Turtle fossils are the most common reptiles found in the Fayoum, including Gigantochersina ammon, a tortoise as large as those living on the Galapagos Islands today. Charles Andrews was the first to write in the West about these tortoises in the early 20th century.

Predynastic slate palettes represent freshwater (soft carapace, Trionyx triunguis) turtles as does the hieroglyph for "turtle" in which the chelonian is always represented from above.[9] Zoomorphic palettes[10] were commonly made in the shapes of turtles.A stone vase in the form of a turtle was found in Naqada.[11] Other art representations of turtles in Ancient Egypt were common.[12]

The earliest representations of the Nile turtle date back to pre-dynastic times and were associated with magical significance that was meant to ward off evil. Amulets and objects with depictions of the turtles represent the turtle as a force to defend health and life.[13][14]

Among Ptah's many creatures, Shetw (Tortoise, Turtle) was neither especially remarkable nor esteemed. Though excluded from lists of animal offerings to the deities, there are nevertheless great quantities of turtle and tortoise bones associated with archaeology at the great ceremonial complex at Heirakonpolis in Upper Egypt. This may suggests that sacrifices of Chelonians served some ritual or liturgical purpose within the ancient Egyptian ceremonial system.[15]

As an aquatic animal, the turtle was associated with the Underworld.[16] The turtle was associated with Set, and so with the enemies of Ra who tried to stop the solar barque as it traveled through the underworld. Since the XIXth Dynasty, and particularly in the Late and Greco-Roman periods, turtles were known to have been ritually speared by kings and nobles as evil creatures.[9]

The famous Hunters Palette shows most of the hunters carrying a kind of shield which was interpreted as a turtle-carapace shield.[9] In an Early Dynastic tomb at Helwan a man was buried beneath the carapace of a tortoise who had lost his feet in an accident. The carapace may symbolize the "way in which the owner used to move slowly like a tortoise," or sitting in the carapace may have been a very useful way for the owner to move around.[9]

The Medical Ebers Papyrus cites the use of turtle carapaces and organs in some formulas,[9] including one formula for the removal of hair.[17] An ointment made from the brain of a turtle was the treatment for squinting.[18] Parts of turtles were used to grind eye paint, which was applied both as a cosmetic and to protect eyes from infection and over-exposure to sun, dust, wind, and insects.[13][19]

The flesh of Trionyx was eaten from Predynastic times to as late as the Old Kingdom, and later the flesh of turtles began to be considered an "abomination of Ra" and the role of these animals became an evil one. Turtle carapaces and scutes from Red Sea Turtles (Chelonia Imbricata) were used in rings, bracelets, dishes, bowls, knife hilts, amulets, and combs. Land tortoise carapaces from Kleinmann's tortoise were used as sounding boards for lutes, harps and mandolins.[9] Turtle shells were also used to make norvas, an instrument resembling a banjo.[20]

In a meticulously documented discussion, Fischer traces the Nile turtle's decline in popularity as food, showing that while eaten in Predynastic, Archaic, and Old Kingdom periods, turtles were used only for medicinal purposes after the Old Kingdom. Carapaces were used well into the New Kingdom.[21] In reliefs and paintings of the Old, Middle, and Early New Kingdoms, the turtle is depicted rarely, and is depicted as an innocuous reptile. After Dynasty XIX, the turtle is usually depicted as a malignant creature associated with Apophis and subject to ritual extermination. Fischer shows that in Predynastic and Archaic times, objects of daily use, such as cosmetic palettes, dishes, and vessels, were made in the shapes of turtles, while after the Old and Middle Kingdoms representations of turtles are more often found on amuletic objects and furniture. After the Middle Kingdom, the turtle's shape is very rarely associated with any object which would come into close contact with a person, a fact which reflects the increasing explicit hostility shown to turtles in scenes and texts.[22]

Ancient Mesopotamia

In ancient Mesopotamia, the turtle was associated with the god Ea and was used on kudurrus as a symbol of Ea.[23] The heron and the turtle is an Ancient Sumerian story that has survived to this day.[24]

Ancient Greece and Rome

One of Aesop's fables is The Tortoise and the Hare.

The tortoise was the symbol of the ancient Greek city of Aegina, on the island by the same name: the seal and coins of the city shows images of tortoises. The word Chelonian comes from the Greek Chelone, a tortoise god.[7] The tortoise was a fertility symbol in Greek and Roman times, and an attribute of Aphrodite/Venus.[25] Aphrodite Ourania, is draped rather than nude Aphrodite with her foot resting on a tortoise at Musée du Louvre.

The playwright Aeschylus was said to have been killed by a tortoise dropped by a bird.

Asia

Malaysia

Ketupat penyu is made from a coconut leaf to appear like a turtle. It is used in a ritual to banish the ghosts in Malay traditional medicine.

China

In China the traditional Chinese character symbolizing the turtle (龜) shows a head like that of a snake at the top, to the middle left of the paws, to the middle right of the shell, and at the bottom of the tail. According to the "Book of ceremonies", the single-horned rhino, phoenix, tortoise, and dragon are the four entities that possess spirit. Tortoise shells were used for divination during the ancient Chinese Shang Dynasty and carry the earliest specimens of Chinese writing. Some Chinese are of the opinion that their script was taken from the signs on the back of the tortoise.

For the Chinese, the tortoise is sacred and symbolizes longevity, power, and tenacity. It is said that the tortoise helped Pangu (also known as P'an Ku) create the world: the creator goddess Nuwa or Nugua cuts the legs off a sea turtle and uses them to prop up the sky after Gong Gong destroys the mountain that had supported the sky. The flat plastron and domed carapace of a turtle parallel the ancient Chinese idea of a flat earth and domed sky.[26] For the Chinese as well as the Indians, the tortoise symbolizes the universe. Quoting Pen T'sao, "the upper dome-shaped part of its back has various signs, which correspond with the constellations on the sky, and this is Yan; the lower part has many lines, which relate to the earth and is the Yin.[7]

The tortoise is one of the "Four Fabulous Animals",[2] the most prominent beasts of China. These animals govern the four points of the compass, with the Black Tortoise the ruler of the north, symbolizing endurance, strength, and longevity.[27] The tortoise and the tiger are the only real animals of the four, although the tortoise is depicted with supernatural features such as dragon ears, flaming tentacles at its shoulders and hips, and a long hairy tail representing seaweed and the growth of plant parasites found on older tortoise shells that flow behind the tortoise as it swims. The Chinese believe that tortoises come out in the spring when they change their shells, and hibernate during the winter, which is the reason for their long life.[7]

The Chinese Imperial Army carried flags with images of dragons and tortoises as symbols of unparalleled power and inaccessibility, as these animals fought with each other but both remained alive. The dragon cannot break the tortoise and the latter cannot reach the dragon.[7] In China, the tortoise was also called the Black warrior, standing as a symbol of power, tenacity, and longevity, as well as that of north and winter. A tortoise was often put at the base of burial monuments. Legend holds that the wooden columns of the Temple of Heaven in Beijing were built on the shells of live tortoises since people thought that these animals were capable of living for more than 3000 years without food or water and are adorned with a magical power that prevents wood from rotting.

It was considered that the tortoise does not remember the day and month of its birth so calling someone a "tortoise" in China was considered offensive.

In Tibet, the tortoise is a symbol of creativity.[7]

The tortoise is of the feng shui water element[28] with the tiger, phoenix, and dragon representing the other three elements. According to the principles of feng shui the rear of the home is represented by the Black Tortoise, which signifies support for home, family life, and personal relationships. A tortoise at the back door of a house or in the backyard by a pond is said to attract good fortune and many blessings. Three tortoises stacked on top of each other represent a mother and her babies.[28] In Daoist art, the tortoise is an emblem of the triad of earth-humankind-heaven.[29]

The tortoise is a symbol of longevity, with a potential lifespan of ten thousand years.[2] Due to its longevity, a symbol of a turtle was often used during burials. A burial mound might be shaped like a turtle, and even called a "grave turtle." A carved turtle, known as bixi was used as a plinth for memorial tablets of high-ranking officials during the Sui Dynasty (581-618 CE) and the Ming periods (1368-1644 CE). Enormous turtles supported the memorial tablets of Chinese emperors[27] and support the Kangxi Emperor's stele near Marco Polo Bridge in Beijing, China. Tortoise shells were used for witchcraft and future forecasting. There are innumerable tales on the longevity of the tortoises and their ability to transform into other forms.[7]

India

In Hindu mythology the world is thought to rest on the backs of four elephants who stand on the shell of a turtle.[30] In Hinduism, Akupara is a tortoise who carries the world on his back, upholding the Earth and the sea.[2]

One Avatar of Vishnu is the giant turtle Kurma. The Sri Kurmam Temple in Andhra Pradesh, India, is dedicated to the Kurma avatar. Kurmavatara is also Kasyapa, the northern star, the first living being, forefather of Vishnu the protector. The plastron symbolizes the earthly world and the carapace the heavenly world. The Shatapatha Brahmana identifies the world as the body of Kurmaraja, the "king of tortoises", with the earth its plastron, the atmosphere its body, and the vault of the heavens its carapace. The tortoise holds the elephant, on which rests the earth. The elephant is the masculine symbol and the tortoise the feminine.[7]

Japan

Japanese culture adopted from China the myth of four Guardian Beasts, said in Japan to protect the city of Heian (Kyoto) from threats arising from each of the four cardinal directions. The Black Tortoise or Gen-bu, sometimes depicted as a combination of a tortoise and a snake, protects Kyoto from the north; the other beasts and associated directions are the Azure Dragon (Sei-ryu, east), the Vermilion Bird (Su-zaku, south), and the White Tiger (Byak-ko, west).

In Japan, however, the turtle has developed a more independent tradition than the other three prominent beasts of China. The minogame (蓑亀), which is so old it has a train of seaweed growing on its back, is a symbol of longevity and felicity. A minogame has an important role in the well-known legend of Urashima Tarō.

According to traditional Japanese beliefs, the tortoise is a haven for immortals and the world mountain, and symbolizes longevity, good luck, and support. It is the symbol of Kumpira, the god of seafaring people.[7]

The tortoise is a favored motif by netsuke-carvers and other artisans, and is featured in traditional Japanese wedding ceremonies.[2] There is also a well-known artistic pattern based on the nearly hexagonal shape of a tortoise's shell. These patterns are usually composed of symmetrical hexagons, sometimes with smaller hexagons within them.[31]

Vietnam

Many legends of Vietnam connect closely to the turtle. During the time of Emperor Yao in China, a Vietnamese King's envoy offered a sacred turtle (Vietnamese: Thần Quy) which was carved in Khoa Đẩu script on its carapace writing all things happening from the time Sky and Earth had been born. Yao King ordered a person to copy it and called it Turtle Calendar.

Another legend told that Kim Quy Deity (Golden Turtle Deity) came into sight and crawled after An Dương Vương's pray. Following the Deity's foot prints, An Dương Vương built Cổ Loa Citadel as a spiral. An Dương Vương was given a present of Kim Quy Deity's claw to make the trigger (Vietnamese: lẫy), one part of the crossbow (Vietnamese: nỏ) named Linh Quang Kim Trảo Thần Nỏ that was the military secret of victorious Zhao Tuo.

A 15th-century legend tells that Lê Lợi returned his sacred sword named Thuận Thiên (Heaven's Will) to Golden Turtle in Lục Thủy lake after he had won Ming's army. That is why Lục Thủy lake was renamed Sword Lake (Vietnamese: Hồ Gươm) or Returning Sword lake (Hoàn Kiếm Lake). This action symbolizes taking leave of weapons for peace.

Taiwan

In Taiwanese villages, paste cakes of flour shaped like turtles are made for festivals that are held in honor of the lineage patron deity. People buy these cakes at their lineage temple and take them home to assure prosperity, harmony, and security for the following year.[27]

North America

The World Turtle carries the Earth upon its back in myths from North America; for this reason many aboriginal North Americans refer to it as Turtle Island. In Cheyenne tradition, the great creator spirit Maheo kneads some mud he takes from a coot's beak until it expands so much that only Old Grandmother Turtle can support it on her back. In Mohawk tradition, the trembling or shaking of the Earth is thought of as a sign that the World Turtle is stretching beneath the great weight that she carries.[5]

Indians of North America used combs made of tortoise shell to signify the margin between life and death. According to their beliefs, the cosmic tree emerges from the spine of the tortoise.[7]

The expression "turtles all the way down" comes from the notion of the World Turtle.

South America

Turtles are beloved by many Indigenous South American cultures and have thus entered their mythologies. According to many of these myths, the Jebuti (Portuguese: jabuti, pronounced: [ʒɐbuˈtʃi], "land turtle") obtained its mottled shell in a fall to earth as it attempted to reach the heavens with the help of an eagle in order there to play a flute at a celebration.[32]

Oceania

Tahiti

In the Tahitian islands, the tortoise is the shadow of the gods and the lord of the oceans.[7]

Polynesia

In Polynesia the tortoise personified the war god Tu. Drawing tattoo marks of a tortoise was a custom among warriors.[7]

In a story from Admiralty Island, people are born from eggs laid by the World Turtle. There are many similar creation stories throughout Polynesia.[5]

In Religion

Islam

In Sufism the hatching and return of baby turtles to the sea is a symbol for returning to God through God's guidance.[33] The journey of the baby turtle is a good model for the Quranic verse "Extol the name of your Lord, the Highest, who has created and regulated, and has destined and guided" [87:1-3].

Judaism

According to the laws of Kashrut (Kosher), the turtle is considered "impure" and cannot be eaten.

Back when the Jews still had the temple, when a woman completed her period, she had to give two pigeons and two turtles to a Kohen, a priest. The exact passage from the Torah is:

And on the eighth day she shall take unto her two turtles, or two young pigeons, and bring them unto the priest, to the door of the tabernacle of the congregation.— ויקרא, פרשות מצרע (Leviticus 15:29-30)

In this case, however, the "turtle" referred to is a "turtle-dove," a kosher bird, and not a reptile. Reptiles, according to Leviticus, are never kosher for eating or for sacrifice.

In modern fiction

Folk lore

In Aesop's fable The Tortoise and the Hare, a tortoise defeats an overconfident hare in a race.

Literature

(Alphabetical by author's last name)

Thomas King's novel The Back of the Turtle alludes to the idea of the World Turtle.

In Stephen King's The Dark Tower series, the turtle is a prominent figure. Named Maturin, the turtle is one of the twelve guardians of the beams which hold up the dark tower. There is also a small carving of the turtle which is described as a 'tiny god'. A rhyme is recited by the characters, "See the TURTLE of enormous girth, on his shell he holds the Earth." This rhyme and the turtle also show up in King's novel It, where the turtle represents the opposition to the terror that is It.

Turtle is a character who figures prominently in Barbara Kingsolver's novels The Bean Trees and Pigs in Heaven. She is a Cherokee child whose adoptive mother, Taylor Greer, so nicknamed her because Turtle grabs onto Taylor and will not let go. Taylor explains, "In Kentucky where I grew up, people used to say if a snapping turtle gets hold of you it won't let go till it thunders."[34]

In the books by Terry Pratchett, the Discworld is carried on the backs of four elephants, who in turn rest on the back of the gigantic world turtle Great A'Tuin. In the Discworld novel Small Gods, the Great God Om manifests as a tortoise.

In The Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck uses the tortoise as an emblem of the resolve and persistence of the "Okies" that travel west across the US for a better life.[4]

Ursula K. Le Guin's novel "The Lathe of Heaven" introduces a person whose dreams involuntarily become reality. The novel eventually features sea turtle aliens.

Children's literature

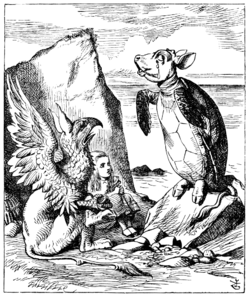

There is a character called the Mock Turtle in Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. In the illustration by John Tenniel, the Mock Turtle is depicted as a turtle with the head, hooves, and tail of a calf; referencing the real ingredients of mock turtle soup.[35]

In the children's story, Esio Trot by Roald Dahl, a character named Mrs. Silver has a small pet tortoise, Alfie, who she loves very much. One morning, Mrs. Silver mentions to Mr. Hoppy that even though she has had Alfie for many years, her pet has only grown a tiny bit and has gained only 3 ounces in weight. She confesses that she wishes she knew of some way to make her little Alfie grown into a larger, more dignified tortoise. Mr. Hoppy suddenly thinks of a way to give Mrs. Silver her wish and (he hopes) win her affection. He eventually begins swapping the tortoise for bigger and bigger ones, with the illusion of using magic.

In children's literature such as Dr. Seuss's Yertle the Turtle, the turtle is often depicted as a humorous character having a mixture of animal and human characteristics.[36][37]

Film and television

- The television show Avatar: The Last Airbender features a magical, ancient, island-sized creature called the "Lion Turtle".

- Duck and Cover was a six-minute civil defense film that starred an animated character called Bert the Turtle.

- Gamera, a Japanese movie monster, is the star of eleven films from 1965 to 2006.

- Kung Fu Panda, an animated movie, has a turtle spiritual master - Oogway.

- The character Rainbow Dash in the show, My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic, has a pet tortoise named Tank.

- The TV British sitcom One Foot in the Grave features a tortoise at the start and end of each episode.

- The British speculative fiction documentary series, The Future is Wild shows a giant descendent of tortoises called the Toraton.

- The Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles are comic book characters whose adventures have been adapted for TV and film. They are Leonardo, Raphael, Donatello, and Michelangelo. They were created in 1983.[38] They were a cultural phenomenon between 1988 and 1992, with their images ubiquitous in advertising, cinema, comics, magazines, music, newspapers, and television.[39] Their action figures were top sellers around the world. In 1990, the cartoon series was shown on more than 125 television stations every day and the comic books sold 125,000 copies a month.[38] Their origin – flushed down the toilet and ending up in the sewer system – echoed contemporary urban legends of small reptiles that were flushed down toilets growing into fierce animals in city sewers.[39]

- Sea Turtles are referred to multiple times in the Pirates of the Caribbean films. First mentioned by Gibbs in The Curse of the Black Pearl about how Sparrow managed to escape the island where Barbossa marooned him years ago. It is stated that two turtles were lashed together by Sparrow with human hair from his back to form a raft. This same trait was apparently used by Will in the second film and the Prison Dog in the third one.

- A trio of Looney Tunes cartoons depicts Bugs Bunny racing the slow-moving Cecil Turtle in a contemporary version of one of Aesop's fables. The cartoons are Tortoise Beats Hare, Tortoise Wins by a Hare and Rabbit Transit. Because of this trio, Cecil is the only character in the Looney Tunes series who consistently gets the better of Bugs.[40]

- For the Hammer Films production of One Million Years B.C., Ray Harryhausen created and animated a giant version of the prehistoric turtle Archelon, which attacked a group of cavemen.

- A running gag in Tomska's asdfmovie series is a character stepping on a turtle with a button on its back. The turtle then explodes. This turtle has become known as Mine Turtle.

Video games

Koopa Troopas (Japanese: ノコノコ Nokonoko) are common enemies in the Mario series which resemble tortoises, usually displayed as henchmen under the direct leadership of Bowser, who is also a Koopa. There are also various other Koopas in the game universe, such as the Koopalings. However, since Nintendo 64, many Koopas are friendly and very peaceful, living in villages like Koopa Village near Toad Town, the capital of Mushroom Kingdom. And one blue-shelled Koopa, Kooper, helps Super Mario in his Adventures against Bowser and his evil henchman.

The Pokémon series has a few species resembling turtles or tortoises. Squirtle, Wartortle, and Blastoise are the water-type 'starter' Pokémon in the Kanto Region. Turtwig, Grotle, and Torterra are likewise the grass-type starter Pokémon of the Sinnoh Region. Shuckle, in the Johto Region, can often be mistaken for a stylised turtle, but is in fact a Mould Pokémon. Tirtouga and Carracosta are can be revived from Fossils in the Unova Region. Blastoise, the final evolved form of Squirtle, is the mascot of the Pokémon Blue video game.

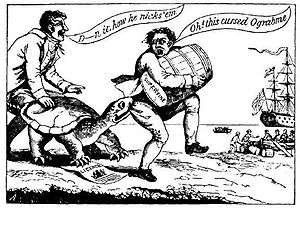

Political use

Various Native American groups use the term "Great Turtle Island" as an alternate term for America, use of the term implying that the continent in question belongs to its indigenous inhabitants and that its conquest and settlement by Europeans was illegitimate.[41]

A post turtle is a reference to a politician who is being manipulated or controlled.

In coins

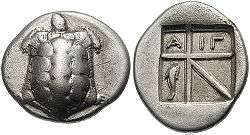

Silver stater obverse Aigina

Silver stater obverse Aigina Greek drachma of Aegina. Obverse: Land Chelone / Reverse: ΑΙΓ(INA) and dolphin. The oldest Aegina Chelone coins depicted sea turtles and were minted ca. 700–550 BC.

Greek drachma of Aegina. Obverse: Land Chelone / Reverse: ΑΙΓ(INA) and dolphin. The oldest Aegina Chelone coins depicted sea turtles and were minted ca. 700–550 BC. Greek drachma of Aegina

Greek drachma of Aegina Coin of Ukraine

Coin of Ukraine Coin of the Russian Federation

Coin of the Russian Federation

In heraldry

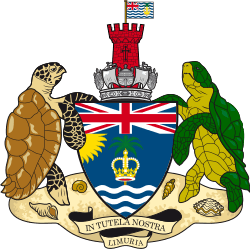

Coat of arms of the Cayman Islands

Coat of arms of the Cayman Islands

Flag of Central Province Solomon Islands

Flag of Central Province Solomon Islands Crottendorf, Germany

Crottendorf, Germany Galapagar, Spain

Galapagar, Spain.png) Gruenheide, Germany

Gruenheide, Germany

Hoppegarten, Germany

Hoppegarten, Germany

In conservation and tourism

Sea turtles are used to promote tourism, as sea turtles can have a symbolic role in the imaginations of potential tourists. Tourists interact with turtles in countries such as Australia, Brazil, Costa Rica, Greece, and the United States. Turtle-based ecotourism activities take place on nesting beaches around the world.[3] Sea turtles are on Tuvalu postage stamps as a national symbol.[3] The mascot of the KAME project is a sea turtle.

Due to the turtle's status as a charismatic megafauna, it is a flagship animal for conservation efforts. Educating the public about turtles and conserving their habitats can positively affect other species living in the same habitats as turtles. Turtles are also used as marketing tools to give products the appearance of being environmentally friendly.[3]

Ecotourism has become popular in Brazil. In Praia do Forte, a marine conservation project called Tamar (from tartaruga marinha or sea turtle) has more than 300,000 visitors every year, who are attracted by the idea of saving the habitat of five endangered sea turtle species that nest on the coast. Tamar uses the sea turtle as a symbol for the need for the protection of the coastal environment. Turtle-related souvenirs are sold to tourists, and hotels are "turtle-friendly": low-rise, dimly lit, and located away from the beach.[42]

At the World Trade Organization's 1999 meeting in Seattle, sea turtles were a focal point of protests.[3] A group of protesters from the Earth Island Institute that focused on the issue of TED use in shrimp trawls wore sea turtle costumes. They brought 500 turtle costumes to the demonstration.[43] Images of protesters wearing turtle costumes were carried in the media, and they became a symbol of the anti-globalization movement.[3]

In Chinese slang

Firstly, tortoises and turtles are regarded as insufficiently virile. “Gui tou” (“turtle’s head”) is a common euphemism for a penis. From this combination turtles are often associated with cuckolds in China. This folk identification may be reinforced by the old Chinese expression "to wear a green hat" (simplified Chinese: 戴绿帽子; traditional Chinese: 戴綠帽子; pinyin: dài lǜmàozi) or "to wear a green scarf" (simplified Chinese: 戴绿头巾; traditional Chinese: 戴綠頭巾; pinyin: dài lǜtóujīn), which derives from sumptuary laws of the Spring-Autumn period (5th to 8th Century BCE) and means "to be a cuckold."

Secondly, "sea turtle" (simplified Chinese: 海龟; traditional Chinese: 海龜; pinyin: hǎi gūi) is slang for a returnee, a Chinese person who has studied abroad and returned home. (There is also a pun here, as hǎi gūi is also 海归, "to come back home from overseas"). The term has positive connotations, implying a dynamic ability to travel across the ocean. By contrast, "kelp" (simplified Chinese: 海带; traditional Chinese: 海帶; pinyin: hǎi dài), is used to describe an unemployed returnee. It has negative overtones, implying the person is drifting aimlessly, and is also a homophonic expression (Chinese: 海待; pinyin: hǎidài, literally "sea waiting").

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Turtles in art. |

- Owen and Mzee, a real-life friendship between an old Aldabra tortoise and a baby hippopotamus.

- Turtle racing

- Turtle soup

- Zaratan

References

- ↑ Cirlot, Juan-Eduardo, trans. Sage, Jack, 2002, A Dictionary of Symbols, Courier Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-42523-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ball, Catherine, 2004, Animal Motifs in Asian Art, Courier Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-43338-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Lutz, Peter L., Musick, John A., and Wyneken, Jeanette, 2002, The Biology of Sea Turtles, CRC Press, ISBN 0-8493-1123-3.

- 1 2 Garfield, Eugene, 1986, The Turtle: A Most Ancient Mystery. Part 1. Its Role in Art, Literature, and Mythology, Towards Scientography: 9 (Essays of An Information Scientist), Isis Press, ISBN 0-89495-081-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Stookey, Lorena Laura, 2004, Thematic Guide to World Mythology, Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-31505-1.

- 1 2 Plotkin, Pamela, T., 2007, Biology and Conservation of Ridley Sea Turtles, Johns Hopkins University, ISBN 0-8018-8611-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 http://www.eedi.org.ua/eem/3-11eng.html

- ↑ File:Rock-painting-turtle.jpg

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Turtles in Predynastic and Early Dynastic Egypt

- ↑ The Prehistory of Egypt

- ↑ Stone vase in the form of a turtle, Naqada culture, Egypt

- ↑ Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Statues, Reliefs and Paintings

- 1 2 http://www.digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk/religion/turtles.html

- ↑ http://ethnology.wordpress.com/category/african-tribesculturescountries/ancient-egypt/

- ↑ http://home.earthlink.net/~fridjian/id7.html

- ↑ Turtle headed watery messenger of Osiris Archived December 12, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Archived June 11, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Ophthalmology in Ancient Egypt

- ↑ Photo of Turtle Palette Archived June 13, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Museum Halls

- ↑ Ancient Egyptian Representations of Turtles book

- ↑ : 133–135. JSTOR 40000646. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Green, Anthony and Black, Jeremy, 1992, Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: an illustrated dictionary, University of Texas Press, ISBN 0-292-70794-0.

- ↑ The heron and the turtle Sumarian Story

- ↑ Bevan, Elinor (1988). "Ancient Deities and Tortoise-Representations in Sanctuaries". The Annual of the British School at Athens. 83: 1–6. doi:10.1017/s006824540002058x.

- ↑ Allan, Sarah, 1991, The Shape of the Turtle: Myth, Art, and Cosmos in Early China, SUNY Press, ISBN 0-7914-0459-5.

- 1 2 3 Simoons, Frederick J., 1991, Food in China: A Cultural and Historical Inquiry, CRC Press, ISBN 0-8493-8804-X.

- 1 2 Moran, Elizabeth, Biktashev, Val and Yu, Joseph, 2002, Complete Idiot's Guide to Feng Shui, Alpha Books, ISBN 0-02-864339-9.

- ↑ Tresidder, Jack, 2005, The Complete Dictionary of Symbols, Chronicle Books, ISBN 0-8118-4767-5.

- ↑ Cobb, Kelton, 2005, The Blackwell Guide to Theology and Popular Culture, Blackwell Publishing, ISBN 1-4051-0698-0.

- ↑ Niwa, Motoji, 2001, trans, Thomas, Jay W., Snow, Wave, Pine: Traditional Patterns in Japanese Design, ISBN 4-7700-2689-7.

- ↑ http://www.lexiline.com/lexiline/lexi73.htm

- ↑ Feild, Reshad Feild, 2002, The Last Barrier: A Journey into the Essence of Sufi Teachings, Publisher: Lindisfarne Books, ISBN 1584200073.

- ↑ Kingsolver, Barbara (1993). Pigs in Heaven. Harper Perennial. p. 78.

- ↑ Reichertz, Ronald, 1997, The Making of the Alice Books, McGill-Queen's Press, ISBN 0-7735-2081-3.

- ↑ Smith-Marder, Paula (2006). "The Turtle and the Psyche". Journal of Psychological Perspectives. 49 (2): 228–248. doi:10.1080/00332920600998262.

- ↑ Goldstein, Jeffrey H., 1994, Toys, Play, and Child Development, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-45564-2.

- 1 2 Long, Mark A., 2002, Bad Fads, ECW Press, ISBN 1-55022-491-3.

- 1 2 Jones, Dudley, and Watkins, Tony, 2000, A Necessary Fantasy?: The Heroic Figure in Children's Popular Culture, Routledge, ISBN 0-8153-1844-8.

- ↑ Lenburg, Jeff, 2006, Who's Who in Animated Cartoons: An International Guide to Film & Television, Hal Leonard, ISBN 1-55783-671-X.

- ↑

- ↑ Levine, Robert M., 1999, The History of Brazil, Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-30390-8.

- ↑ Berg, John C., 2003, Teamsters and Turtles?: U.S. Progressive Political Movements in the 21st Century, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 0-7425-0192-2.

External links

- Sea Turtle Postage Stamps of the World.

- The Appearance of the Spirit Turtle - An article about Japanese turtle folklore at hyakumonogatari.com

- Kathleen Rodgers, Turtles in Literature (S&S Learning Materials, 1997).