Ctenochasmatoidea

| Ctenochasmatoids Temporal range: Late Jurassic - Early Cretaceous, 152–105 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

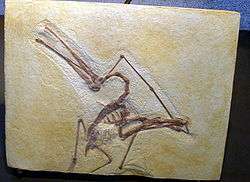

| Fossil specimen of Ctenochasma elegans | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | †Pterosauria |

| Clade: | †Caelidracones |

| Suborder: | †Pterodactyloidea |

| Infraorder: | †Archaeopterodactyloidea |

| Clade: | †Euctenochasmatia Unwin, 2003 |

| Subgroups | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Pterodactylidae Bonaparte, 1838 | |

Ctenochasmatoidea is a group of pterosaurs within the suborder Pterodactyloidea.

Evolutionary history

The earliest known ctenochasmatoid remains date to the Late Jurassic Kimmeridgian age. Previously, a fossil jaw recovered from the Middle Jurassic Stonesfield Slate formation in the United Kingdom, was considered the oldest known. This specimen supposedly represented a member of the family Ctenochasmatidae,[1] though further examination suggested it actually belonged to a teleosaurid stem-crocodilian instead of a pterosaur.[2]

Ecology

Most ctenochasmatoids were aquatic or semi-aquatic pterosaurs, possessing large webbed hindfeet and long torsos - both adaptations for swimming and floating -, as well as a predominant occurrence in aquatic environments, the exception being the more slender-limbed and short-torsoed gallodactylids. They occupied a wide variety of ecological niches, from generalistic carnivores like Pterodactylus to filter-feeders like Pterodaustro and possible molluscivores like Cycnorhamphus. Most common, however, were straight-jawed, needle-toothed forms, some of the most notable being Ctenochasma and Gnathosaurus; these possibly occupied an ecological niche akin to that of modern spoonbills, their teeth forming spatula-like jaw profile extensions, allowing them a larger surface area to catch individual small prey. [3]

Flight

Most ctenochasmatoids have wing proportions akin to those of modern shorebirds and ducks, and probably possessed a similar frantic, powerful flight style. The exception is Ctenochasma, which appears to have had longer wings and was probably more comparable to modern skuas.[4]

Launching varied radically among ctenochasmatoids. In forms like Cycnorhamphus, long limbs and shorter torsos meant a level of relative ease. In forms like Pterodaustro, however, which possessed long torsos and short limbs, launching might have been a more taxing and prolonged affair, only possible in large open areas, just like modern heavy-bodied aquatic birds such as swans, even with the pterosaurian quadrupedal launching.[5]

Classification

Ctenochasmatoidea was first defined by David Unwin in 2003 as the clade containing Cycnorhamphus suevicus, Pterodaustro guinazui, their most recent common ancestor, and all its descendants.[6]

During the 2000s and 2010s, several competing definitions for the various ctenochasmatoid groups were proposed. Pereda-Suberbiola et al. (2012) used Fabien Knoll's (2000) definition of the family-level name Pterodactylidae.[7] Knoll had defined Pterodactylidae as a clade containing "Pterodactylus antiquus, Ctenochasma elegans, their most recent common ancestor and all [its] descendants".[8] Using this definition with the analysis conducted by Pereda-Suberbiola et al. (2012) meant that Ctenochasmatoidea was actually nested inside Pterodactylidae.[7] Below is the majority-rule consensus tree found by Pereda-Suberbiola et al. (2012), showing their preferred definitions of Pterodactylidae and Ctenochasmatoidea.[7]

| Pterodactylidae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

Other researchers, such as David Unwin, have traditionally defined Pterodactylidae in such a way to ensure it is nested within Ctenochasmatoidea instead. In 2003, Unwin defined the same clade (Pterodactylus + Pterodaustro) with the name Euctenochasmatia.[6] Unwin considered this to be a subgroup within Ctenochasmatoidea, but most analyses since have found Pterodactylus to be more primitive than he thought, making Euctenochasmatia the more inclusive group. Below is a cladogram showing the results of a phylogenetic analysis presented by Andres, Clark & Xu (2014) illustrating this view.[2]

| Archaeopterodactyloidea |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

Some studies based on a different type of analysis have found that Ctenochasmatoidea, as usually thought of, is not a natural group (making it paraphyletic). In 2014, Steven Vidovic and David Martill concluded that several pterosaurs traditionally thought of as ctenochasmatoids, specifically Gladocephaloideus, Cycnorhamphus, Aurorazhdarcho, Aerodactylus, and Ardeadactylus, may actually have been more closely related to ornthocheiroids. They found that Pterodactylus itself was actually more primitive than both this new group, the Aurorazhdarchidae, and the classic ctenochasmatids. The results of their analysis are shown below.[9]

| Pterodactyloidea |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

References

- ↑ Buffetaut, E. and Jeffrey, P. (2012). "A ctenochasmatid pterosaur from the Stonesfield Slate (Bathonian, Middle Jurassic) of Oxfordshire, England." Geological Magazine, (advance online publication) doi:10.1017/S0016756811001154

- 1 2 Andres, B.; Clark, J.; Xu, X. (2014). "The Earliest Pterodactyloid and the Origin of the Group". Current Biology. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.030.

- ↑ Witton, Mark P. (2013). Pterosaurs: Natural History, Evolution, Anatomy. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691150613.

- ↑ Witton, Mark P. (2013). Pterosaurs: Natural History, Evolution, Anatomy. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691150613.

- ↑ Witton, Mark P. (2013). Pterosaurs: Natural History, Evolution, Anatomy. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691150613.

- 1 2 Unwin, D. M., (2003). "On the phylogeny and evolutionary history of pterosaurs." Pp. 139-190. in Buffetaut, E. & Mazin, J.-M., (eds.) (2003). Evolution and Palaeobiology of Pterosaurs. Geological Society of London, Special Publications 217, London, 1-347.

- 1 2 3 Xabier Pereda-Suberbiola; Fabien Knoll; José Ignacio Ruiz-Omeñaca; Julio Company; Fidel Torcida Fernández-Baldor (2012). "Reassessment of Prejanopterus curvirostris, a Basal Pterodactyloid Pterosaur from the Early Cretaceous of Spain". Acta Geologica Sinica. 86 (6): 1389–1401. doi:10.1111/1755-6724.12008.

- ↑ Fabien Knoll (2000). "Pterosaurs from the Lower Cretaceous (?Berriasian) of Anoual, Morocco". Annales de Paléontologie. 86 (3): 157–164. doi:10.1016/S0753-3969(00)80006-3.

- ↑ Vidovic, S. U.; Martill, D. M. (2014). "Pterodactylus scolopaciceps Meyer, 1860 (Pterosauria, Pterodactyloidea) from the Upper Jurassic of Bavaria, Germany: The Problem of Cryptic Pterosaur Taxa in Early Ontogeny". PLoS ONE. 9 (10): e110646. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0110646.