Crossrail

| Crossrail | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overview | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other name(s) | Elizabeth line (from December 2018) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Type |

Commuter/suburban rail Rapid transit[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| System | National Rail | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Under construction | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Locale | Greater London; Berkshire, Buckinghamshire, Essex | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Termini |

West: Heathrow Airport / Reading East: Abbey Wood / Shenfield | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stations | 40 (planned) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened |

2015: Liverpool Street to Shenfield section branded TfL Rail 2019: full route expected to open[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operator(s) | MTR Corporation (Crossrail) Ltd[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Depot(s) |

Ilford Old Oak Common Plumstead (if Transport & Works Act Order approved) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rolling stock |

Class 345 9 carriages per trainset[4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line length | approx. 118 km (73 mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Number of tracks | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) standard gauge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrification | 25 kV 50 Hz AC (overhead lines) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operating speed | 140 km/h (90 mph) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

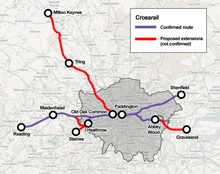

Crossrail is a 118-kilometre (73-mile) railway line under development in London and the home counties of Berkshire, Buckinghamshire and Essex. The central section and a large portion of the line, between Paddington in central London and Abbey Wood in the south-east, are due to open in December 2018; at that time the service will be named the Elizabeth line.[5] The western section beyond Paddington, to Reading in Berkshire and Heathrow Airport, is due to enter operation in December 2019, completing the new east-west route across Greater London. Part of the eastern section, between Liverpool Street and Shenfield in Essex, was transferred to a precursor service called TfL Rail in 2015; this section will be connected to the central route through central London to Paddington in May 2019.

The project was approved in 2007 and construction began in 2009 on the central section of the line – a new tunnel through central London – and connections to existing lines that will become part of Crossrail.[6] It is one of Europe's largest railway and infrastructure construction projects.[7][8][9]

The line will provide a high-frequency commuter and suburban passenger service that will link parts of Berkshire and Buckinghamshire, via central London, to Essex and south-east London. Crossrail will be operated by MTR Corporation (Crossrail) Ltd as a London Rail concession of TfL,[3] in a similar manner to London Overground. It is expected to relieve pressure on existing London Underground lines such as the Central and District lines, which are the current main east-west passenger routes, as well as the Heathrow branch of the Piccadilly line. The need for extra capacity along this corridor is such that the former head of Transport for London, Sir Peter Hendy, predicted that the Crossrail lines will be "immediately full" as soon as they open.[10]

The project's main feature is 21 km (13 mi) of new twin tunnels. The main tunnels will run from Paddington to Stratford and Canary Wharf.[11] An almost entirely new line will branch from the main line at Whitechapel to Canary Wharf, crossing the River Thames, with a new station at Woolwich and connecting with the North Kent Line at Abbey Wood.

Services will run on 136 km (85 mi) of line,[12] sharing parts of existing lines with current services, mainly on parts of the Great Western Main Line in Berkshire, Buckinghamshire and London (between Reading and Paddington) and the Great Eastern Main Line in London and Essex (between Stratford and Shenfield). Nine-carriage Class 345 trains will run at frequencies of up to 24 trains per hour in each direction through the central section.

History

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 1941–48 | First proposals for cross-London railway tunnels put forward by George Dow and examined by the LCC |

| 1974 | DoE/GLC London Rail Study Report recommends a Paddington-Liverpool Street "Crossrail" tunnel |

| 1989 | Central London Rail Study proposes three Crossrail schemes, including an East-West Paddington/Marylebone-Liverpool Street route |

| 1991 | A private Bill promoted by London Underground and British Rail is submitted to Parliament, proposing a new Paddington-Liverpool Street rail tunnel; the bill is rejected by the Private Bill Committee in 1994. |

| 2001 | TfL & DoT promote the Crossrail scheme through Cross London Rail Links (CLRL) |

| 2004 | Senior railway managers promote the expanded regional Superlink scheme |

| 2005 | 2005 Crossrail Bill put before Parliament |

| 2008 | The Crossrail Act 2008 receives Royal Assent on 22 July |

| 2009 | Construction work begins on 15 May 2009 at Canary Wharf |

| 2015 | TfL Rail takes over the first rail services out of Liverpool Street in June (see Services below) |

| 2018 | Core section tunnel to open to passenger services (December) |

| 2019 | Full Crossrail services Reading/Heathrow to Shenfield/Abbey Wood commence (December) |

| 2026 | Possible opening date for new Old Oak Common station |

Planning, financing and proposals

1948 proposals

The concept of large-diameter railway tunnels crossing central London to connect Paddington and Liverpool Street main-line stations was proposed by railwayman George Dow in the London newspaper The Star in June 1941.[13] He also proposed north-south lines, anticipating the Thameslink lines of postwar years. The current Crossrail proposal has its origins in the 1943 County of London Plan and 1944 Greater London Plan by Sir Patrick Abercrombie. These led to a specialist investigation by the Railway (London Plan) Committee, appointed in 1944 and reporting in 1946 and 1948.[14] Route A would have run from Loughborough Junction to Euston, replacing Blackfriars bridge and largely serving the same purpose as today's Thameslink Programme. Route F would have connected Lewisham with Kilburn via Fenchurch Street, Bank, Ludgate Circus, Trafalgar Square, Marble Arch and Marylebone. This was seen as a lower priority than Route A, but Route C was the only one built, as the Victoria line, but with smaller-diameter tube tunnels.

1974 proposals

The term 'Crossrail' emerged in the 1974 London Rail Study Report by a steering group set up by the Department of the Environment and the Greater London Council to look at future transport needs and strategic plans for London and the South East.[15] The report contained several options for new lines and extensions: the development of the Jubilee line (then called the Fleet Line) to Fenchurch Street; the Jubilee Line Extension (River Line) project; and the Chelsea–Hackney line. The re-opening of the Snow Hill Tunnel was proposed, as were two deep-level railway lines:[16][17]

- Northern Tunnel, Paddington to Liverpool Street, via Marble Arch, Bond Street/Oxford Circus, Leicester Square/Covent Garden (interchange), and Holborn/Ludgate (close to Paternoster Square);

- Southern Tunnel, Victoria to London Bridge, via Green Park/Piccadilly, Leicester Square/Covent Garden (interchange), Ludgate/Blackfriars, and Cannon Street/Monument.

The 1974 study estimated that 14,000 passengers would be carried in the peak hour in the northern tunnel between Paddington and Marble Arch and 21,000 between Liverpool Street and Ludgate Circus, which would also carry freight. Higher estimates were made for the southern tunnel. It commented that Crossrail would be similar to the RER in Paris and the Hamburg S-Bahn. Reference was also made to through services to Heathrow Airport. Although the idea was seen as imaginative, only a brief estimate of cost was given: £300 million. A feasibility study was recommended as a high priority so that the practicability and costs of the scheme could be determined. It was also suggested that the alignment of the tunnels should be safeguarded[18] while a final decision was taken.

1989 proposals

The "Central London Rail Study" (1989) proposed standard (BR) structure gauge tunnels linking the existing rail network as the "East-West Crossrail", "City Crossrail", and "North-South Crossrail" schemes. The East-West scheme was for a line from Liverpool Street to Paddington/Marylebone with two connections at its western end linking the tunnel to the Great Western Main Line and to the Metropolitan line. The City route was shown as a new connection across the City of London linking the Great Northern Route with London Bridge. The North-South line proposed routing West Coast Mainline, Thameslink and Great Northern Route trains through Euston and King's Cross/St Pancras, then under the West End via Tottenham Court Road, Piccadilly Circus and London Victoria towards Crystal Palace and Hounslow. The report also recommended a number of other schemes including a "Thameslink Metro" line enhancement, and a new underground Chelsea Hackney line. Cost of the east-west scheme including rolling stock was estimated at £885 million.[19]

In 1991 a private bill was submitted to Parliament for a scheme including a new underground line from Paddington to Liverpool Street.[20] The bill was promoted by London Underground and British Rail, and supported by the government; the bill was rejected by the Private Bill Committee in 1994,[21] on the grounds that a case had not been made, though the Government issued "Safeguarding Directions", protecting the line route from development that would jeopardise future schemes.[22]

2001 proposals

In 2001 Cross London Rail Links (CLRL), a 50/50 joint venture company between Transport for London and the Department for Transport, was formed to develop and promote the scheme,[23] and also a Wimbledon-Hackney scheme. In 2003 and 2004, over 50 days of exhibitions were held to explain the proposals at over 30 different locations.[24]

2004 Superlink proposal

A more ambitious proposal named "Superlink" was proposed in 2004, at an estimated cost of £13 billion, including additional infrastructure work outside London: in addition to Crossrail's east-west tunnel, lines would connect towns including Cambridge, Ipswich, Southend, Pitsea, Reading, Basingstoke and Northampton. According to the scheme's promoters, the line would carry four times as many passengers and require a lower public subsidy as a result.[25] The proposal was rejected by Crossrail,[26] and failed to receive the backing of the Mayor of London, Ken Livingstone, or the Department for Transport.[27]

Ladbroke Grove (Kensal Gasworks, Portobello Central)

The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea was pushing for an additional station in the north of the borough, east of Old Oak Common, at Kensal[29][30] off Ladbroke Grove and Canal Way. A turn-back facility, now built west of Paddington, could have been sited at Kensal to have provided a frequent service to a new station to regenerate that area.[31][32][33] Mayor Boris Johnson agreed that a station would be added if it met three tests: it must not delay construction of Crossrail, it did not compromise performance of Crossrail or any other railway, and it must not increase Crossrail's overall cost. So the council agreed to underwrite the projected £33 million cost,[34] and a consultancy study that then concluded a Kensal station would not compromise Crossrail.

TfL conducted a feasibility study on the station,[35] and the project was supported by local MPs, the residents of the Borough, National Grid, retailers Sainsbury's and Cath Kidston, and Jenny Jones (Green Party member of the London Assembly).[36] It was also supported by the adjoining London Borough of Brent.[37] However, the three Mayoral tests set not met, and in early 2013 it was indicated that neither the DfT nor TfL supported the construction of the station, and construction continued without planning for a station at Kensal. There was official closure of the issue in April 2013.[38]

The plans were briefly resurrected by former Mayor Boris Johnson in 2016[39][40] but not by incoming Mayor Sadiq Khan.[41]

New railway approved

The Crossrail Bill 2005, a hybrid bill, went through Parliament. The Crossrail Bill Select Committee met between December 2005 and October 2007.[42] The Select Committee announced an interim decision in July 2006 which called on the promoter to add a station at Woolwich. The Government initially responded that it would not do so as it would jeopardise the affordability of the whole scheme, but this station was later agreed. While the bill was still in discussion, Secretary of State for Transport Ruth Kelly issued safeguarding directions in force from 24 January 2008, which protect the path of the proposal and certain extensions beyond it from development which might prevent the Crossrail proposal or possible future extensions.[43] In February 2008 the bill moved to the House of Lords, where it was amended by a committee of peers. The act received Royal Assent on 22 July 2008 as the Crossrail Act 2008.[44][45] The act is accompanied by an environmental impact statement, plans and other related information.[46] The act gives Cross London Rail Links the powers necessary to build the line. In November 2008, while announcing an agreement for a £230 million contribution from BAA (now known as Heathrow Airport Holdings Limited), Transport Minister Lord Adonis confirmed that funding was still in place despite the global economic downturn.[47] On 4 December 2008 it was announced that Transport for London and the Department for Transport had signed the Crossrail Sponsors' Agreement. This commits them to financing the project, then projected to cost £15.9 billion, with further contributions from Network Rail, BAA and the City of London. The accompanying Crossrail Sponsors' Requirements commits them to the construction of the full scheme.

Prime Minister Gordon Brown and Mayor of London Boris Johnson attended a ceremony at Canary Wharf on 15 May 2009 when construction started.[48] On 7 September 2009 the project received £1 billion in funding. The money is being lent to Transport for London by the European Investment Bank.[49]

In the lead-up to the 2010 general election, both the Labour and Conservative parties made manifesto commitments to deliver the railway. The Transport Secretary appointed in May 2010 confirmed that the newly elected coalition government was committed to the project.[50] The original planned schedule was that the first trains would run in 2017. In 2010 a Comprehensive Spending Review identified savings of over £1 billion in projected costs, achieved by a simpler, but slower, tunnelling strategy to reduce the number of tunnel boring machines and access shafts required, with trains planned to run on the central section from 2018.[51]

Construction of new line

In April 2009, Crossrail announced that 17 firms had secured 'Enabling Works Framework Agreements' and would now be able to compete for packages of works.[52] At the peak of construction up to 14,000 people are expected to be needed in the project's supply chain.[53][54]

Work began on 15 May 2009 when piling works started at the future Canary Wharf station.[55]

The threat of diseases being released by work on the project was raised by Lord James of Blackheath at the passing of the Crossrail Bill. He told the House of Lords select committee that 682 victims of anthrax had been brought into Smithfield in Farringdon with some contaminated meat in 1520 and then buried in the area.[56] On 24 June 2009 it was reported that no traces of anthrax or bubonic plague had been found on human bone fragments discovered during tunnelling.[57]

Invitations to tender for the two principal tunnelling contracts were published in the Official Journal of the European Union in August 2009. 'Tunnels West' (C300) was for twin 6.2 kilometres (3.9 mi)-long tunnels from Royal Oak through to the new Crossrail Farringdon Station, with a portal west of Paddington. The 'Tunnels East' (C305) request was for three tunnel sections and 'launch chambers' in east London.[58] Contracts were awarded in late 2010: the 'Tunnels West' contract was awarded to BAM Nuttall, Ferrovial Agroman and Kier Construction (BFK); the 'Tunnels East' contract was awarded to Dragados and John Sisk & Son.[59][60] The remaining tunnelling contract (C310, Plumstead to North Woolwich), which included a tunnel under the Thames, was awarded to Hochtief and J. Murphy & Sons in 2011.[61]

By September 2009, preparatory work for the £1 billion developments at Tottenham Court Road station had begun, with buildings (including the Astoria Theatre) being compulsorily purchased and demolished.[62]

In March 2010, contracts were awarded to civil engineering companies for the second round of 'enabling work' including 'Royal Oak Portal Taxi Facility Demolition', 'Demolition works for Crossrail Bond Street Station', 'Demolition works for Crossrail Tottenham Court Road Station' and 'Pudding Mill Lane Portal'.[63] In December 2010, contracts were awarded for most of the tunnelling work.[64]

In December 2011, a contract to ship the excavated material from the tunnel to Wallasea Island[65] was awarded to a joint venture comprising BAM Nuttall Limited and Van Oord UK Limited.[66][67] Between 4.5 and 5 million tonnes of soil will be used to construct a new wetland nature reserve (Wallasea Wetlands).[65][68] The project eventually moved seven million tons of earth.[69]

In March 2013 excavations uncovered 13 skeletons 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in) under the road that surrounds the gardens in Charterhouse Square, Farringdon. The remains are thought to be of victims of the Black Death in the 14th century.[70][71]

Boring of the railway tunnels was officially completed at Farringdon on 4 June 2015 in the presence of the Prime Minister and the Mayor of London.[72]

Eye of the Needle

The "Eye of the Needle" is a name that the contractors gave to a place at Tottenham Court Road station where the new tunnel had to go over existing Northern line tunnels and under an escalator tunnel, with less than a metre clearance on both top and bottom (including 85 centimetres (33 in) clearance on the bottom with the Northern line tunnels).[73]

Health, safety, and industrial relations

In May 2012, a BFK manager challenged their subcontractor, Electrical Installations Services Ltd. (EIS), saying that one of their electricians was a trade union activist. Some days later, Pat Swift, the HR manager for BFK and a regular user of the Consulting Association, again challenged EIS. EIS refused to dismiss their worker and lost the contract. Flash pickets were held at the Crossrail site and also at the sites of the BFK partners. The Scottish Affairs Select Committee called on the UK Business Secretary, Vince Cable, to set up a government investigation into blacklisting at Crossrail.[74][75] The electrician was reinstated.[76]

In September 2012, a gantry supporting a spoil hopper at a construction site near Westbourne Park tube station, used to load rail wagons with excavated waste, collapsed, tipping sideways and causing the adjacent Network Rail line to be closed.[77][78]

On 7 March 2014, Rene Tkacik, a Slovakian construction worker, was killed by a piece of falling concrete while working in a tunnel.[79] In April 2014, The Observer reported details of a leaked internal report, compiled for the Crossrail contractors by an independent safety consultancy. The report was claimed to indicate poor industrial relations over safety issues and that workers were "too scared to report injuries for fear of being sacked".[80]

Design

Crossrail is based on new east-west tunnels under central London connecting the Great Western Main Line near Paddington and the Great Eastern Main Line near Stratford. An eastern branch diverges at Whitechapel, running through Docklands and emerging at Custom House on a disused part of the North London Line, and continuing under the River Thames to Abbey Wood. Trains will run from Reading[12][81] and Heathrow in the west to Shenfield and Abbey Wood in the east. Services east of Stratford (to Shenfield) and west of Paddington (to Heathrow and Reading) will replace existing stopping services and run on existing slow lines.

The tunnelled sections will be about 22 kilometres (14 mi) in length.

Name and identity

The line will be named the Elizabeth line after Queen Elizabeth II from its opening in Central London in December 2018.[5] The Elizabeth line will use a version of the Transport for London roundel, coloured purple with a blue bar and the Elizabeth line name in TfL's New Johnston font.[82]

Tunnels

There are five tunnelled sections, each with an internal diameter of 6.2 m (20 ft 4 in)[83] (compared with 3.81 m (12 ft 6 in) for the deep-tube Victoria line), totalling 21 km (13 mi) in length: a 6.4 km (4.0 mi) tunnel from Royal Oak to Farringdon; an 8.3 km (5.2 mi) tunnel from Limmo Peninsula (in Canning Town) to Farringdon; a 2.7 km (1.7 mi) tunnel from Pudding Mill Lane to Stepney Green; a 2.6 km (1.6 mi) tunnel from Plumstead to North Woolwich (Thames tunnel section); and a 0.9 km (0.6 mi) tunnel from Limmo Peninsula (Royal Docks) to Victoria Dock portal which will re-use the Pudding Mill-Stepney tunnelling machines. Each section consists of two tunnels excavated at the same time – two TBMs per section. The tunnel linings are constructed from concrete sections, some of which are produced in Chatham Dockyard then transported by barge to the Limmo Peninsula. Tunnelling is expected to progress at around 100 m (330 ft) per week.[83] The main tunnelling contracts are valued at around £1.5 billion.[84] The wide diameter tunnels allow for Class 345 rolling stock, which is larger than the traditional deep-level underground trains. The tunnels allow for the emergency evacuation of passengers through the side doors rather than along the length of the train. When bicycles are allowed to be carried it is regarded as essential to allow evacuation to the sides of the train.[85]

Tunnel boring machines

The project used eight 7.1-metre (23-foot) diameter tunnel-boring machines (TBM) from Herrenknecht AG (Germany). Two types are used; 'slurry' type for the Thames tunnel, which involves tunnelling through chalk; and 'Earth Pressure Balance Machines' (EPBM) for tunnelling through clay, sand and gravel (at lower levels through Lambeth Group and Thanet Sands ground formation). The TBMs weigh nearly 1,000 tonnes and are over 100 metres (330 feet) long.[83][86]

The TBMs were named following tunnelling tradition. Crossrail ran a competition in January 2012 in which over 2500 entries were received and 10 pairs of names short-listed. After a public vote in February 2012, the first three pairs of names were announced on 13 March:[87]

- Ada and Phyllis, Royal Oak to Farringdon section, named after Ada Lovelace and Phyllis Pearsall.

- Victoria and Elizabeth, Limmo Peninsula to Farringdon section, named after Queen Victoria and Queen Elizabeth II.

- Mary and Sophia, Plumstead to North Woolwich section, named after the wives of Isambard Kingdom Brunel and Marc Isambard Brunel.

On 16 August 2013, the two names for the last pair of TBMs were announced:[88]

- Jessica and Ellie, Pudding Mill Lane to Stepney Green and Limmo Peninsula to Victoria Dock sections, named after Jessica Ennis-Hill and Ellie Simmonds.

Western section

The western section is on the surface from Reading to Acton Main Line, with an underground spur to Heathrow Airport, and upgraded stations at Maidenhead, Taplow, Burnham, Slough, Langley, Iver, West Drayton, Hayes and Harlington, Southall, Hanwell, West Ealing, Ealing Broadway and Acton Main Line. Reading station has already been redeveloped.

The Heathrow branch includes stations at Heathrow Terminal 4 and Heathrow Central and joins the main route at Airport Junction, between West Drayton and Hayes & Harlington.

Crossrail had been planned to end at Maidenhead, with an extension to Reading safeguarded.[43] On 27 March 2014, it was announced that the line would go to Reading.[12][81][89]

Central section

The central tunnels run from a portal just west of London Paddington station to Whitechapel, with further tunnelling to Stratford and to Canary Wharf.

There will be new stations at Paddington, Bond Street, Tottenham Court Road, Farringdon-Barbican (for Thameslink), Liverpool Street-Moorgate and Whitechapel, with interchange with the London Underground, other National Rail services and the Docklands Light Railway. Due to the size and positioning of new platforms, some will be connected to two underground stations.

Eastern sections

Whitechapel to Shenfield

.jpg)

This section runs underground from Whitechapel to Stratford then on the surface on existing lines. It will include the following stations: Stratford, Maryland, Forest Gate, Manor Park, Ilford, Seven Kings, Goodmayes, Chadwell Heath, Romford, Gidea Park, Harold Wood, Brentwood, and Shenfield.

Maryland was not included until August 2006, when selective door opening was agreed so that the station would be accessible.[90]

Whitechapel to Abbey Wood

This section runs underground from Whitechapel to Canary Wharf, then to Abbey Wood. It takes over the Custom House to Woolwich via Connaught tunnel stretch of the former North London Line (built by the Eastern Counties and Thames Junction Railway) and connects it with the North Kent Line via a tunnel under the River Thames at North Woolwich. It will include a 'station box' at Woolwich,[91] however efforts to connect Crossrail with London City Airport were not fruitful.[92]

Restoration of the Connaught tunnel by filling with concrete foam and reboring, as originally intended, was deemed too great a risk to the structural integrity of the tunnel, and so the docks above were drained to give access to the tunnel roof in order to enlarge its profile. This work took place during 2013.[93][94]

Services

The Elizabeth line will run a familiar London Underground all-stops service in the core section, but the western section will run skip-stop with only Heathrow trains calling at Hanwell and Acton Mainline, and only Reading/Maidenhead trains calling at West Ealing (all trains passing through the other stations will stop there). The Eastern section has an extra peak hour 4 trains per hour (tph) service from Gidea Park to Liverpool Street mainline station that will not enter the core section. Like the Bakerloo line's outer sections, the Elizabeth line will share platforms and rails with other services outside the tunnelled sections. About two-thirds of all Elizabeth line westbound trains will terminate after Paddington, one quarter of peak-hour Elizabeth line trains to/from the north-east section will start/end at Liverpool Street main line platforms, bypassing Whitechapel.

| Section | Morning peak Crossrail service |

Off-peak Crossrail services |

|---|---|---|

| Central Section (Paddington to Whitechapel) |

24tph consisting of: 4tph Abbey Wood – Heathrow Terminal 4 6tph Abbey Wood – Paddington 2tph Abbey Wood – West Drayton 8tph Shenfield – Paddington 2tph Shenfield – Reading 2tph Shenfield – Maidenhead |

16tph consisting of: 4tph Abbey Wood – Heathrow Terminal 4 4tph Abbey Wood – Paddington 4tph Shenfield – Paddington 2tph Shenfield – Reading 2tph Shenfield – Maidenhead |

| Shenfield branch[95] | 16tph consisting of: 8tph Shenfield – Paddington 2tph Shenfield – Reading 2tph Shenfield – Maidenhead 4tph Gidea Park – Liverpool Street mainline station. |

8tph consisting of: 4tph Shenfield – Paddington 2tph Shenfield – Reading 2tph Shenfield – Maidenhead |

| Abbey Wood branch[96] | 12tph consisting of: 4tph Abbey Wood – Heathrow Terminal 4 6tph Abbey Wood – Paddington 2tph Abbey Wood – West Drayton |

8tph consisting of: 4tph Abbey Wood – Heathrow Terminal 4 4tph Abbey Wood – Paddington |

| Reading and Heathrow branches[97] |

10tph consisting of: 4tph Abbey Wood – Heathrow Terminal 4 2tph Abbey Wood – West Drayton 2tph Shenfield – Reading 2tph Shenfield – Maidenhead |

8tph consisting of: 4tph Abbey Wood – Heathrow Terminal 4 2tph Shenfield – Reading 2tph Shenfield – Maidenhead |

In addition there will be non Crossrail services at some stations:

Heathrow Express – Paddington Main Line (4tph).

Greater Anglia services at Shenfield (5tph), Romford (2tph) and Stratford (5tph).

Great Western services at Reading (2tph), Twyford (2tph), Maidenhead (2tph), Slough (2tph) and Ealing Broadway (2tph).

| Trains per hour peak[98][99] | Trains per hour off-peak | Calling pattern [100] |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 2 | Shenfield – Reading Shenfield, Brentwood, Harold Wood, Gidea Park, Romford, Chadwell Heath, Goodmayes, Seven Kings, Ilford, Manor Park, Forest Gate, Maryland, Stratford, Whitechapel, Liverpool St-Moorgate, Farringdon-Barbican, Tottenham Court Road, Bond St, Paddington, Ealing Broadway, West Ealing, Southall, Hayes & Harlington, West Drayton, Iver, Langley, Slough, Burnham, Taplow, Maidenhead, Twyford, Reading. |

| 2 | 2 | Shenfield – Maidenhead Shenfield, Brentwood, Harold Wood, Gidea Park, Romford, Chadwell Heath, Goodmayes, Seven Kings, Ilford, Manor Park, Forest Gate, Maryland, Stratford, Whitechapel, Liverpool St-Moorgate, Farringdon-Barbican, Tottenham Court Road, Bond St, Paddington, Ealing Broadway, West Ealing, Southall, Hayes & Harlington, West Drayton, Iver, Langley, Slough, Burnham (peak only), Taplow (peak only), Maidenhead. |

| 8 | 4 | Shenfield – Paddington Shenfield, Brentwood, Harold Wood, Gidea Park, Romford, Chadwell Heath, Goodmayes, Seven Kings, Ilford, Manor Park, Forest Gate, Maryland, Stratford, Whitechapel, Liverpool St-Moorgate, Farringdon-Barbican, Tottenham Court Road, Bond St, Paddington. |

| 4 | 4 | Abbey Wood – Heathrow Terminal 4 Abbey Wood, Woolwich, Custom House, Canary Wharf, Whitechapel, Liverpool St-Moorgate, Farringdon-Barbican, Tottenham Court Road, Bond St, Paddington, Acton Mainline, Ealing Broadway, Hanwell, Southall, Hayes & Harlington, Heathrow Central, Heathrow Terminal 4 |

| 6 | 4 | Abbey Wood – Paddington Abbey Wood, Woolwich, Custom House, Canary Wharf, Whitechapel, Liverpool St-Moorgate, Farringdon-Barbican, Tottenham Court Road, Bond St, Paddington. |

| 2 | 0 | Abbey Wood – West Drayton Abbey Wood, Woolwich, Custom House, Canary Wharf, Whitechapel, Liverpool St-Moorgate, Farringdon-Barbican, Tottenham Court Road, Bond St, Paddington, Ealing Broadway, Southall, Hayes & Harlington, West Drayton. |

| 4 | 0 | Gidea Park – Liverpool Street Main Line platforms Gidea Park, Romford, Chadwell Heath, Goodmayes, Seven Kings, Ilford, Manor Park, Forest Gate, Maryland, Stratford, Liverpool St Main Line platforms. |

Start of services

Prior to the opening of the main tunnel under central London, it is planned to transfer passenger operations on the outer branches of the Crossrail system to TfL for inclusion in the Crossrail concession. This transfer will take place in several stages from May 2015. Services will begin running through the central tunnel section in 2018, although a full east-west service will not begin until December 2019 due to signalling changes on the Great Western Main Line.[102][103]

During the initial phase of operation, rail services are to be operated by MTR under the TfL Rail brand. Following the practice adopted during the transfer of former Silverlink services to London Overground in 2007, TfL will carry out a deep clean of stations and rolling stock on the future Elizabeth line route, install new ticket machines and ticket gates, introduce Oyster card and contactless payment at non-London stations, and ensure all stations are staffed. Existing rolling stock is to be rebranded with the TfL Rail identity.[101]

| Stage | Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | May 2015 | Existing services between Liverpool Street (main line station) and Shenfield transferred from Abellio Greater Anglia to TfL Rail |

| 1 | May 2017 | New Class 345 trains brought into service |

| 2 | May 2018 | Existing services between Paddington (main line station) and Heathrow Terminal 4 transferred from Heathrow Connect to Crossrail, as well as shuttle services between Heathrow Central and Heathrow Terminal 4 transferred from Heathrow Express |

| 3 | December 2018 | Services between Paddington (Elizabeth line station) and Abbey Wood begin; route rebranded as Elizabeth line |

| 4 | May 2019 | Services between Paddington (Elizabeth line station) and Shenfield via Liverpool Street (Elizabeth line station) begin |

| 5 | December 2019 | Full route opens, linking Abbey Wood and Shenfield to Heathrow Airport via Paddington, and existing services between Reading and Paddington transferred to Crossrail and extended to Abbey Wood and Shenfield |

Signalling

The signalling will be a mixture of ETCS 2 on the western branches from 2019, CBTC with ATO on the core and Abbey Wood branch (with a possible later upgrade to ETCS), and AWS with TPWS on the Great Eastern Main Line.[102][104][105]

Electrification

Crossrail will use 25 kV, 50 Hz AC overhead line, as on the Great Eastern Main Line and the Great Western Main Line as far as Heathrow. Overhead electrification will be installed between Heathrow Airport junction and Reading as part of the Crossrail project and Great Western Main Line upgrade.

Rolling stock

Crossrail has registered the designation Class 345 for its trains.[106] The requirement is for 65 trains, each 200 metres (660 feet) long and carrying up to 1,500 passengers.[106] The trains will be disabled-accessible, including dedicated areas for wheelchairs, with audio and visual announcements, CCTV and speaker phones to the driver in case of emergency.[107] Crossrail has stated that the new trains will be based on existing designs to minimise costs associated with development.[108]

They are intended to run at up to 160 kilometres per hour (100 mph) on the surface and 100 kilometres per hour (60 mph) in the tunnels.[109] The government's rolling stock plan (2008) expected that the stock for Crossrail would be similar to the new rolling stock procured for the Thameslink Programme and would displace Class 315 EMUs, Class 165 DMUs and Class 360/2 EMUs for use elsewhere on the national network.[110]

In March 2011, Crossrail announced that five bidders had been shortlisted for the contract to build the Class 345 and its associated depot.[111] One of the bidders, Alstom, withdrew from the process in July 2011. In February 2012 Crossrail issued an invitation to negotiate to CAF, Siemens, Hitachi and Bombardier, with tenders expected to be submitted in mid-2012.[112]

Siemens will provide signalling and control systems for Crossrail.[113]

On 6 February 2014, Transport for London and the Department for Transport announced that the contract to build and maintain the new rolling stock had been awarded to Bombardier Transportation.[4] The contract between TfL and Bombardier covers the supply, delivery and maintenance of 65 new trains and a depot at Old Oak Common. The trains will be built at Bombardier's Litchurch Lane manufacturing facility in Derby. This contract will support around 760 UK manufacturing jobs plus 80 apprenticeships. An estimated 74 per cent of contract spend is expected to remain in the UK economy.[114] The design will be based on Bombardier's Aventra design.

Initial services

Although the Elizabeth line's main through service will not begin until around 2019, MTR Crossrail started running services on 31 May 2015, taking over the operation of the local service between Liverpool Street and Shenfield from Greater Anglia (GA) under the TfL Rail brand. For these services it has taken over a number of GA's Class 315 EMUs until the new Elizabeth line-branded Class 345 units have been delivered and commissioned.

Stations

Crossrail requires significant work on station infrastructure. Although initially the trains will be 200 metres (660 feet) long, platforms at the ten new stations in the central core are being built to enable 240-metre-long trains in case passenger numbers make this necessary. At existing stations platforms will be lengthened accordingly.[115]

Maryland and Manor Park will not have platform extensions, so they will use selective door opening.[116] For Maryland this is because of the prohibitive cost of extensions and the poor business case,[117] and for Manor Park it is due to a freight loop that would otherwise be cut off.[118]

A mock-up of the new stations has been built in Bedfordshire to ensure that their architectural integrity would last for a century.[115] It is planned to bring at least one mock-up to London for the public to try out the design and give feedback before final construction takes place.[119]

Of the 40 stations, 32 will have step-free access to both platforms;[120] train doors will be level with the platforms at central stations and at Heathrow. The stations will be fully equipped with CCTV[107] and, due to the length of the platforms, train indicators will be above the platform-edge doors in central stations.[119]

Depot

Crossrail will have two depots, in west London at Old Oak Common and east London at a new signalling centre at Romford.[121][122]

Ticketing

Ticketing is intended to be integrated with the other London transport systems, and Oyster pay as you go will be valid. Travelcards will be valid within Greater London with the exception of the Heathrow branch, which will continue to be subject to special fares. Crossrail has often been compared to Paris' RER system due to the length of the central tunnel. Crossrail will be integrated with the London Underground and National Rail networks, and it is planned to include it on the standard London Underground Map.

Passenger numbers

Crossrail has predicted annual passenger numbers of 200 million from its opening in late 2018; this would represent a considerable increase on the 1,300 million carried on the Underground in 2014–15.[123]

Plans

New stations

Woolwich

The opening of the new Crossrail station will reduce the journey time from Woolwich to Canary Wharf, Bond Street and Heathrow stations to just eight minutes, 21 minutes and 47 minutes respectively.[124] The construction of a station at Woolwich was not proposed as part of the original Crossrail route. However, the House of Commons Select Committee recognised its inclusion in March 2007.[124] When Crossrail becomes operational in 2018, the new station located on the south-east section of the route will see up to 12 trains an hour. It will run during peak hours, connecting south-east London and the Royal Docks with Canary Wharf, central London and beyond.[124]

The Woolwich station is being built on the south-east portion of the Crossrail line that ends at Abbey Wood. The Woolwich redevelopment site at Royal Arsenal is a waterside housing and retail development area adjacent to the Woolwich station. It is spread across approximately 30 hectares of land and is being developed by Berkeley Homes.[124] The site is being developed with the construction of approximately 2,517 new homes, in addition to the 1,248 homes already built.[125] The area also includes a new heritage quarter along with the Greenwich Heritage Centre and Royal Artillery Museum, as well as infrastructural developments such as retail stores, restaurants and cafés, offices, hotels and a cinema.[125]

A 276-metre-long (906-foot) box station sits below a major housing development site. The minimalist, straightforward design will provide entry into the station from a single 30-metre-wide (98-foot) bronze clad portal.[125] Natural light will enter through the main entrance and ceiling into the ticket hall, whilst a connection to daylight is present below ground on the platforms.[125] Set back from the main street and surrounded by a series of heritage listed buildings and a large retail unit, the station acts as a simple portal connecting all these elements together.[125] The station entrance opens out on to Dial Arch Square, a green space, flanked by a series of Grade I and II listed buildings. In addition to enhancing the experience in and out of the station, the urban realm design also helps connect the station with the wider town centre.[125] In addition to the station improvements, Crossrail has been working with the Royal Borough of Greenwich on proposals for improvements to the area around the station.[125]

Old Oak Common

As part of the former Labour government's plans for the High Speed 2 rail link from London to Birmingham, a Crossrail-High Speed 2 interchange would be built at Old Oak Common (between Paddington and Acton Main Line stations). This would be built as part of High Speed 2 (which would start construction, under Labour's plans, in 2017), so would not be built in the first phase of Crossrail. It would provide interchange to other mainline and TfL lines. The succeeding Conservative-Liberal Democrat government adopted that proposal in the plans it put forward for public consultation. This means it is likely to go forward as part of High Speed 2, potentially giving Crossrail an interchange with High Speed 2, the Great Western Main Line (GWML), Central line and London Overground services running through the area.

This would lead to the demolition of the Old Oak Common MPD, the last steam-era shed still standing in London. It was announced in 2008 that Crossrail had acquired the shed, with the indication that the shed would have to go before Crossrail opened in 2014. This related to the original G. J. Churchward-designed roundhouse (originally housed four turntables, now reduced to one), and the British Railways-built Blue Pullman shed built to house the Class 251 and 261 trains running between London Paddington, Birmingham, Wolverhampton, and Bristol. The compulsory purchase order used to acquire Old Oak Common does not include the carriage workshop there, or the Old Oak Common TMD used by GWR further down the line.

Silvertown (London City Airport)

London City Airport has proposed the re-opening of Silvertown railway station, in order to create an interchange between the rail line and the airport.[126] The self-funded £50m station plan is supported 'in principle' by the London Borough of Newham.[127] Provisions for re-opening of the station were made in 2012 by Crossrail LTD.[128] However, it is alleged by the airport that Transport for London is hostile to the idea of a station on the site, a claim disputed by TfL.[129]

Extensions

To Reading

According to the original plans, the western terminus of Crossrail was planned to be Maidenhead. Various commentators advocated an extension of the route further west as far as Reading, especially as it was seen as complementary to the Great Western Electrification project which was announced in July 2009.[131] A Reading terminus was also recommended by Network Rail's 2011 Route Utilisation Strategy.[132]

The UK Government and Transport for London evaluated the option of extending to Reading[133] and in March 2014 it was announced that the extension from Maidenhead to Reading would form part of the core Crossrail network from the outset.[12][81][89]

There was controversy about Crossrail in Reading. The Labour council supported an extension to Reading[134] but the Conservative MP for Reading East, Rob Wilson, expressed concerns that Crossrail trains (which will call at every station) will actually be slower than the present Reading-Paddington service. According to Wilson, "We need the right Crossrail, not any Crossrail".[135] Most existing fast services between Reading and Paddington will remain after the introduction of Crossrail, however, as there are only paths for the additional two services per hour which the latter will provide.

To the West Coast Main Line

Network Rail's July 2011 London & South East Route Utilisation Strategy (RUS) recommended diverting West Coast Main Line (WCML) services from stations between London and Milton Keynes Central away from Euston, to Crossrail via Old Oak Common, to free up capacity at Euston for High Speed 2. This would provide a direct service from the WCML to the Shenfield, Canary Wharf and Abbey Wood, release London Underground capacity at Euston, make better use of Crossrail's capacity west of Paddington, and improve access to Heathrow Airport from the north.[136] Under this scheme, all Crossrail trains would continue west of Paddington, instead of some of them terminating there. They would serve Heathrow Airport (10 tph), stations to Maidenhead and Reading (6 tph), and stations to Milton Keynes Central (8 tph).[137]

In August 2014, a statement by the transport secretary Patrick McLoughlin indicated that the government was actively evaluating the extension of Crossrail as far as Tring, with potential Crossrail stops at Wembley Central, Harrow & Wealdstone, Bushey, Watford Junction, Kings Langley, Apsley, Hemel Hempstead and Berkhamsted. The extension would relieve some pressure from London Underground and London Euston station while also increasing connectivity. Conditions to the extension are that any extra services would not affect the planned service pattern for confirmed routes, as well as affordability.[138][139] This proposal was subsequently shelved in August 2016 due to "poor overall value for money to the taxpayer".[140]

To Gravesend and Hoo Junction

The route to Gravesend has been safeguarded by the Department for Transport, although it was made clear that as at February 2008 there was no plan to extend Crossrail beyond the then-current scheme.[141] The following stations are on the protected route extension to Gravesend: Belvedere, Erith, Slade Green, Dartford, Stone Crossing, Greenhithe for Bluewater, Swanscombe, Northfleet, and Gravesend.[142]

Heathrow Express

The RUS also proposes integrating Heathrow Express services from Heathrow Terminal 5 into Crossrail to relieve the GWML and reduce the need for passengers to change at Paddington.[143]

New lines

Crossrail 2 (Chelsea–Hackney)

Crossrail 2 is a proposed rail route in South East England, running from nine stations in Surrey to three in Hertfordshire providing a new rail link across London on the Crossrail network. It would connect the South Western Main Line to the West Anglia Main Line, via Victoria and Kings Cross St. Pancras, intended to alleviate severe overcrowding that would otherwise occur on commuter rail routes into Central London by the 2030s.

Management and franchise

Crossrail is being built by Crossrail Ltd, jointly owned by Transport for London and the Department for Transport until December 2008, when full ownership was transferred to TfL. Crossrail has a £15.9 billion funding package in place[144] for the construction of the line. Although the branch lines to the west and to Shenfield will still be owned by Network Rail, the tunnel will be owned and operated by TfL.[145]

On 18 July 2014, TfL London Rail said that MTR Corp had won the concession to operate the services for eight years, with an option for two more years.[3] The concession will be similar to London Overground.[146] It is planned to initially let the franchise for eight years from 2015,[3] taking over control of Shenfield metro services from Abellio Greater Anglia in May 2015,[3] and Reading / Heathrow services from Great Western Railway in 2018.[103]

In anticipation of an May 2015 transfer of Shenfield to Liverpool Street services from the Greater Anglia franchise to Crossrail, the invitation to tender for the 2012–2013 franchise required the new rail operator to set up a separate "Crossrail Business Unit" for those services before the end of 2012. This unit was to allow transfer of services to the new Crossrail Train Operating Concession (CTOC) operator during the next franchise.[145][147]

Controversy

There had been complaints from music fans, as the redevelopment of the area forced the closure of a number of historic music venues. The London Astoria,[148] the Astoria 2, The Metro, Sin nightclub and The Ghetto have been demolished to allow expansion of the ticket hall and congestion relief at Tottenham Court Road tube station in advance of the arrival of Crossrail.

There was considerable annoyance in Reading that Crossrail would terminate at Maidenhead, not Reading.[149] The promoters and the government had always stressed that there was nothing to prevent extension to Reading in future if it could be justified. In February 2008 it was announced that the route for an extension to Reading was being safeguarded.[150] This became more likely once the government announced that the Great Western Main Line was to be electrified beyond Reading regardless of Crossrail. In March 2014 it was announced that the route would indeed be extended to Reading.[151]

In February 2010, Crossrail was accused of bullying residents whose property lay on the route into selling up for less than the market value.[152] A subsequent London Assembly report was highly critical of the insensitive way in which Crossrail had dealt with compulsory purchases and the lack of assistance given to the people and businesses affected.[153]

See also

- British Rail Class 341 and 342, proposed rolling stock for an earlier unbuilt Crossrail scheme

- 21st-century modernisation of the Great Western Main Line

- Heathrow Airtrack

- Heathrow Connect, which will be taken over by Crossrail

- Proposed railway electrification in Great Britain

- Rail transport in the United Kingdom

- Shenfield metro, which will be taken over by Crossrail.

- Thameslink Programme, upgrading of existing north-south line through central London

- East Side Access

References

- ↑ "TfL Rail: What we do".

- ↑ "TfL launches competition to find operator to run Crossrail services" (Press release). Transport for London. 12 March 2013. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "MTR selected to operate Crossrail services". Railway Gazette International. 18 July 2014.

- 1 2 "Bombardier wins Crossrail train contract". Railway Gazette International. 6 February 2014.

- 1 2 Jobson, Robert (23 February 2016). "Crossrail named the Elizabeth line: Royal title unveiled as the Queen visits Bond Street station". London Evening Standard. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ↑ Thomas, Nathalie (26 August 2013). "Going underground on Crossrail: A 40-year project is taking shape". The Telegraph. London.

- ↑ "Crossrail's giant tunnelling machines unveiled". BBC News. 2 January 2012.

- ↑ "Digging deep: Europe's biggest infrastructure project". Allianz Global Corporate & Specialty. 4 July 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ↑ "Europe's Largest Construction Project". Crossrail Ltd. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ↑ "Bagehot: London is Working." The Economist (London). 1 August 2015: 52. Print

- ↑ "42 kilometres of new rail tunnels under London". Crossrail. 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "London Crossrail plans extended to Reading". BBC News. 27 March 2014. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ↑ Dow, Andrew (2005). Telling the Passenger Where to Get Off. London: Capital Transport. pp. 52–55. ISBN 9781854142917.

- ↑ Jackson, Alan A.; Croome, Desmond F. (1962). Rails Through The Clay. London: Allen & Unwin. pp. 309–312. OCLC 55438.

- ↑ London Rail Study Report Part 2, pub. GLC/DoE 1974, pp. 87–88.

- ↑ London Rail Study Part 2, Fig. 15.7

- ↑ Young, John (29 November 1974). "Investment of £1,390m in London rail urged". The Times. London. p. 4.

- ↑ "Safeguarding". Crossrail. n.d. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ↑ British Rail Network SouthEast; London Regional Transport; London Underground (January 1989). "Central London Rail Study". Department of Transport. pp. 11–16; maps 3, 6 & 7.

- ↑ "Crossrail Bill". 1991.

- ↑ "Crossrail". Hansard. 20 June 1994.

- ↑ "Select Committee on the Crossrail Bill : 1st Special Report of Session 2007–08: Crossrail Bill" (PDF). 1: Report. House of Lords. Chapter 1. Introduction: The History of Crossrail, p.8.

- ↑ "Sponsors and Partners". Crossrail.

Crossrail Limited is the company charged with delivering Crossrail. Formerly known as Cross London Rail Links (CLRL), it was created in 2001 [..] Established as a 50/50 joint venture company between Transport for London and the Department for Transport, Crossrail Limited became a wholly owned subsidiary of TfL on 5 December 2008

- ↑ "History of Crossrail". Crossrail. n.d. Archived from the original on 2 June 2009.

- ↑ Sources:

- "Rival cross-city rail plan aired". BBC News. 15 December 2004.

- Murray, Dick (15 December 2004). "Superlink to rival Crossrail unveiled". London Evening Standard.

- Hansford, Mark (17 December 2004). "Superlink weighs in to Crossrail contest". New Civil Engineer.

- "Call to expand Crossrail's route". BBC News. 16 October 2007.

- ↑ Department for Transport (2007). Further Responses to the Government's Consultation on the Crossrail Bill Environmental Statement. p. 35. ISBN 9780101724920.

(quoted from CLRL response, section 3.74) Following a careful review of the Superlink proposal, CLRL concluded that it was not a feasible option and did not merit further analysis.

- ↑ Clement, Barrie (16 December 2004). "Crossrail will fail, say backers of rival plan". The Independent. London.

- ↑ "Google Maps". Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ↑ "Portobello Crossrail station the missing link in renaissance of Portobello Road" (Press release). Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. 11 July 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ↑ "Supporting Kensal Crossrail". Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. n.d. Retrieved 26 June 2011.

- ↑ "Case for a Crossrail station gains momentum" (Press release). Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. 1 July 2010.

- ↑ Bloomfield, Ruth (24 August 2010). "Study to explore adding Crossrail station at Kensal Rise". Building Design. London.

- ↑ "Crossrail at Kensal Rise back on the cards?". London Reconnections (blog). 27 August 2010.

- ↑ "Council to pay for Crossrail station". London Evening Standard. 25 March 2011.

- ↑ "Case Closes on Crossrail at Kensal – London Reconnections". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ↑ Kensal Crossrail station would 'transform' the area, says deputy mayor. Regeneration + Renewal. 16 May 2011.

- ↑ "Brent backs plans for Kensal Crossrail" (Press release). Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. 27 September 2011. Retrieved 30 September 2011.

- ↑ "NO CROSSRAIL FOR KENSAL". Kensington Labour Party. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ↑ Cooper, Goolistan (14 March 2016). "Plans for Ladbroke Grove Crossrail station resurrected by Boris". Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ↑ "Crossrail might get an extra station". 14 March 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ↑ "DELIVERING YOUR MANIFESTO" (PDF). Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ↑ "Crossrail Bill Select Committee". UK Parliament. Archived from the original on 29 September 2008. Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- 1 2 "SAFEGUARDING DIRECTIONS FOR DEVELOPMENT AFFECTING THE ROUTE AND ASSOCIATED WORKS PROPOSED FOR THE CROSSRAIL PROJECT – MAIDENHEAD TO OLD OAK COMMON, OLD OAK COMMON TO ABBEY WOOD, STRATFORD TO SHENFIELD AND WORKS AT WEST HAM, PITSEA AND CLACTON-ON-SEA" (PDF).

- ↑ "Crossrail Bill 2005". Crossrail. Archived from the original on 3 August 2009. Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- ↑ "BBC NEWS – UK – England – Soho shops make way for Crossrail". bbc.co.uk.

- ↑ "Orders of the Day – Crossrail Bill". TheyWorkForYou.com. 19 July 2005. Retrieved 23 March 2007.

- ↑ "Crossrail gets £230m BAA funding". BBC News. 4 November 2008. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- ↑ Hill, Dave (15 May 2009). "Work on London's £16bn Crossrail scheme begins". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- ↑ "Crossrail project gets £1bn loan". BBC News. 7 September 2009.

- ↑ "New coalition government makes Crossrail pledge". BBC News. 15 April 2010. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- ↑ "Mayor secures vital London transport investment and protects frontline services" (Press release). Transport for London. 20 October 2010. Archived from the original on 17 August 2012.

- ↑ Owen, Ed (9 April 2009). "Crossrail enabling works frameworks announced". nce.co.uk. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ↑ "Careers". Crossrail. n.d. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ↑ "Crossrail pledges 14,000 jobs boom for Londoners". London Evening Standard. 11 October 2007. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ↑ Gerrard, Neil (15 May 2009). "Work officially starts on Crossrail". Contract Journal. London. Archived from the original on 17 May 2009.

- ↑ "House of Lords – Crossrail Bill Examination of Witnesses (Questions 12705–12719)". UK Parliament. 2008. Retrieved 24 June 2009.

- ↑ "No anthrax in Crossrail remains". BBC News. 24 June 2009. Retrieved 24 June 2009.

- ↑ "Crossrail tunnelling contracts advertised" (Press release). Crossrail. 25 August 2009. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ↑ "Crossrail awards major tunnelling contracts worth £1.25bn" (Press release). Crossrail. 10 December 2010.

- ↑ "Crossrail tunnel factory in Kent at full production". BBC News. 16 April 2013. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ↑ "Hochtief and Vinci win last Crossrail tunnels". The Construction Index. 4 August 2011.

- ↑ "Crossrail station profile: Tottenham Court Road". New Civil Engineer. London. 24 September 2009. Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- ↑ "Crossrail to awards second round of enabling contracts". New Civil Engineer. London. 16 March 2010. Retrieved 17 March 2010.

- ↑ "Crossrail awards tunnelling contracts". Railway Gazette International. London. 13 December 2010. Retrieved 13 December 2010.

- 1 2 Carrington, Damian (17 September 2012). "Crossrail earth to help create biggest man-made nature reserve in Europe". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- ↑ "Crossrail awards contract to ship excavated material to Wallasea Island" (Press release). Crossrail. 16 December 2011.

- ↑ "Monster lift sends east London tunnelling machines 40 metres underground". Crossrail. 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- ↑ Morelle, Rebecca (17 September 2012). "Wallasea Island nature reserve project construction begins". BBC News. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- ↑ "From railway to wildlife". Daily Telegraph. 3 March 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- ↑ Eleftheriou, Krista (15 March 2013). "14th century burial ground discovered in Central London" (Press release). Crossrail. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ↑ "'Black Death' victims unearthed as Crossrail excavations reveal 12 Middle Ages skeletons". Metro. London. 15 March 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ↑ MacLennan, Peter (4 June 2015). "Prime Minister and Mayor of London celebrate completion of Crossrail's tunnelling marathon" (Press release). Crossrail. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ↑ Butcher, David. "The Fifteen Billion Pound Railway — Series 1 – 1. Urban Heart Surgery". Radio Times. London. Retrieved 27 August 2014.

- ↑ Smith, Dave; Chamberlain, Phil (2015). Blacklisted The Secret War between Big Business and Union Activists. New Internationalist. ISBN 978-0745333984.

- ↑ Matthew Taylor (28 July 2013). "Construction industry blacklisting is unacceptable, warns Vince Cable". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- ↑ "Crossrail Blacklist Victory Party". Northern Voices. 21 September 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ↑ Lewis, Mark (28 September 2012). "Gantry collapse at Westbourne Park Crossrail site". Construction News.

- ↑ Freeman, Simon (28 September 2012). "Waste hopper collapses at Paddington station". London Evening Standard.

- ↑ "Slovakian identified as killed Crossrail worker". BBC News. 12 March 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- ↑ Boffey, Daniel (27 April 2014). "Crossrail managers accused of 'culture of spying and fear'". The Observer. London. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Crossrail extended to Reading". Department for Transport. Department for Transport. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ↑ Bull, John (12 March 2013). "Crossrail Gets Its Roundel". London Reconnections. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- 1 2 3 Sources:

- "Crossrail Tunnel Boring Machines". Crossrail.

- "Crossrail information paper: D8 – Tunnel construction methodology" (PDF). Crossrail. 20 November 2007.

- Thomas, Tris (22 September 2011). "Herrenknecht supply final Crossrail TBMs". Tunneling Journal.

- ↑ "Crossrail awards remaining tunnelling contracts as Crossrail's momentum becomes unstoppable" (PDF) (Press release). Crossrail. 7 April 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 April 2011.

- ↑ Crossrail Bill: 1st Special Report of Session 2007–08, Vol. 2: Evidence. The Stationery Office. 19 August 2008. pp. 148–150. ISBN 978-0-10-401354-0.

- ↑ Sources:

- "Bulletin: The giant burrowers" (PDF) (23). Crossrail. 2011.

- Symes, Claire (14 December 2011). "Crossrail's first TBM ready for delivery". New Civil Engineer. London.

- ↑ "Names of our first six tunnel boring machines announced". Crossrail. 13 March 2012.

- ↑ "Olympic champions join Crossrail's marathon tunnelling race". Crossrail. 16 August 2013.

- 1 2 "DfT and TfL extend Crossrail route to Reading" (Press release). Transport for London. 27 March 2014.

- ↑ "Plans for London's Crossrail project". Planning Resource. 11 August 2006. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 10 June 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- ↑ "London City Airport Consultative Committee – Surface Access". Archived from the original on 16 May 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ↑ "Crossrail team gain confidence". Modern Railways. London. July 2012. p. 37.

- ↑ "Connaught Tunnel restoration complete", Global Rail News, accessed 8 March 2014

- ↑ Eastern section Crossrail

- ↑ South-east section Crossrail

- ↑ Crossrail

- ↑ "Elizabeth line (Eastern section) timetable" (PDF). Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ↑ "Elizabeth line (Western section) timetable" (PDF). Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ↑ "Crossrail Infrastructure Consultation" (PDF). Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- 1 2 Smith, Howard. "Crossrail – Moving to the Operating Railway Rail and Underground Panel 12 February 2015" (PDF). 12 February 2015. Transport for London. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 February 2015. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- 1 2 "Now it's 2019: Crossrail's stealth delay". BorisWatch (blog). 8 June 2011.

- 1 2 "TfL Board Meeting Summary: DLR, Overground and Other Ways of Travelling". London Reconnections (blog). 2 October 2008.

- ↑ "Crossrail starts tender process for signalling system" (Press release). Crossrail. 14 April 2011.

- ↑ "Crossrail Rolling Stock Tender is Issued". London Reconnections (blog). 1 December 2010.

- 1 2 "Crossrail rolling stock and depot contract to be awarded to Bombardier" (Press release). Department for Transport. 6 February 2014. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- 1 2 "Crossrail demonstrates commitment to disability equality" (Press release). Crossrail. 21 September 2009.

- ↑ "Crossrail outlines progress on delivering value for money" (Press release). Crossrail. 27 September 2010. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- ↑ Crossrail information: Rolling Stock.

- ↑ "Rolling stock plan". Department for Transport. 30 January 2008. Archived from the original on 5 June 2008.

- ↑ "Crossrail issues rolling stock shortlist". Railway Gazette International. London. 30 March 2011.

- ↑ "Crossrail rolling stock contract invitations to negotiate issued". Railway Gazette International. London. 28 February 2012.

- ↑ "Siemens withdraws from Crossrail bid". BBC News. 5 July 2013. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ↑ "Bombardier wins £1bn Crossrail deal". BBC News. 6 February 2014. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- 1 2 Hyde, John (16 March 2011). "Crossrail 'mock-ups' for stations that will last 100 years" Archived 6 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine.. Docklands 24.

- ↑ Nicholls, Matt (11 April 2011). "Forest Gate station Crossrail design work contract awarded". Newham Recorder.

- ↑ "House of Lords Select Committee on the Crossrail Bill: Minutes of Evidence". UK Parliament. 27 May 2008.

- ↑ "House of Lords Select Committee on the Crossrail Bill: Minutes of Evidence (Questions 1060 – 1079)". UK Parliament. 27 May 2008.

- 1 2 "Future of London transport revealed at secret site". BBC News. 16 March 2011.

- ↑ "Crossrail Route Map". Crossrail. Crossrail. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ↑ "BBC News". Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- ↑ "Route Window NE9 Romford station and depot (east)" (PDF). Retrieved 26 May 2016.

- ↑ "Crossrail in numbers".

- 1 2 3 4 "Crossrail Woolwich Station". railway-technology.com.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Woolwich station". crossrail.co.uk.

- ↑ https://www.londoncityairport.com/content/pdf/TransformingEastLondon.pdf

- ↑ https://www.newham.gov.uk/Documents/Environment%20and%20planning/Matter%209%20Written%20Statement%20-%20London%20City%20Airport.pdf

- ↑ http://web.archive.org/web/20150705231549/http://74f85f59f39b887b696f-ab656259048fb93837ecc0ecbcf0c557.r23.cf3.rackcdn.com/assets/library/document/s/original/silvertown_station.pdf

- ↑ Broadbent, Giles (31 May 2016). "Why is TfL so hostile to a Crossrail station at LCY?". Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ↑ Rail Utilisation Strategy, 2011, pp. 153

- ↑ Owen, Ed (23 July 2009). "Crossrail to Reading would keep it on track". New Civil Engineer. London.

- ↑ Rail Utilisation Strategy, 2011, pp. 9.

- ↑ "Britain's Transport Infrastructure – Rail Electrification" (PDF). Department for Transport. July 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 April 2010.

- ↑ "Crossrail bid supported by Lord Adonis". Reading Post. 20 November 2013. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- ↑ "Rob campaigns for "New & Improved" Crossrail Service to Reading" (Press release). Rob Wilson MP. 22 November 2013. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- ↑ Rail Utilisation Strategy, 2011, pp. 150.

- ↑ "'Emerging scenario' suggests Crossrail to the West Coast Main Line". Rail. Peterborough. 10 August 2011. p. 8.

- ↑ "Crossrail extension to Hertfordshire being considered". BBC News. 7 August 2014. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ↑ Topham, Gwyn (7 August 2014). "New Crossrail route mooted from Hertfordshire into London". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ↑ "Crossrail off the tracks as plans are shelved – Hemel Gazette". Retrieved 2016-08-06.

- ↑ Harris, Tom (6 February 2008). "Crossrail Safeguarding Update 2008". Department for Transport. Retrieved 16 February 2008.

- ↑ "Crossrail Safeguarding Directions Abbey Wood to Gravesend and Hoo Junction (Volume 4)" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-07-29.

- ↑ Rail Utilisation Strategy, 2011, pp. 10.

- ↑ "The future of Crossrail". House of Commons. 5 November 2007.

- 1 2 Greater Anglia Franchise Invitation to Tender 21 April 2011. Department for Transport. p.27.