Cretan resistance

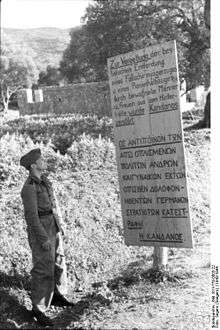

The text reads: "Kandanos was destroyed in retaliation for the bestial ambush murder of a paratrooper platoon and a half-platoon of military engineers by armed men and women."

The Cretan resistance (Greek: Κρητική Αντίσταση) was a resistance movement against the occupying forces of Nazi Germany and Italy by the residents of the Greek island of Crete during World War II. Part of the larger Greek Resistance, it lasted from May 20, 1941, when the German Wehrmacht invaded the island in the Battle of Crete, until the autumn of 1945 when they surrendered to the British. For the first time during World War II, attacking German forces faced in Crete a substantial resistance from the local population. Cretan civilians picked off paratroopers or attacked them with knives, axes, scythes or even bare hands. As a result, many casualties were inflicted upon the invading German paratroopers during the battle.

Development

The Cretan resistance movement was formed very quickly after the Battle of Crete, with an initial planning meeting on 31 May 1941. It brought together a number of different groups and leaders and was initially termed the PMK (Πατριωτικó Μέτωπο Κρήτης – Patriotic Front of Crete), but later changed the name to EAM (Εθνικó Απελευθερωτικó Μέτωπο – National Liberation Front) like the principal communist-led resistance movement on the mainland. The primary objective of the movement on the one hand was to support the Cretan people under occupation by boosting morale, providing information, and distributing of food at a time of great deprivation (due to confiscations by the Germans and Italians), and on the other hand to undertake certain operations against the Germans, including a number of sabotage operations. A notable success was the battle to prevent the destruction of Kastelli airport by the Germans as they were leaving eastern Crete.[1]

Communication by boat with Egypt was established as a means of evacuating Allied soldiers who had been trapped on the Island and for bringing in supplies and men to liaise with Cretan resistance fighters.

Leading figures in the EAM resistance movement included Yiannis Podias,[2]:245 Miltiades Porfirogenis, Manolis Pitikakis, Nikos Samaritis, Nikos Raiinos, Emmanuel Manousakis, Rousos Koundouros and Mitsos Pappas.

The non-communist pole was formed under the name National Organization of Crete (EOK) (with Andreas Papadakis as leader). Other resistance figures included Georgios Petrakis who had close ties with EOK and SOE.

Communication between EOK and EAM was poor, with open hostility breaking out between EOK and ELAS, a sub group of EAM, in January 1945 at the siege of Retimo.[2]:306

As Cretan fighters became better armed and more aggressive in 1944, the German troops pulled out of the country areas, having destroyed a number of Kedros villages, killing the inhabitants, to frighten the Cretans.[2]:284 Grouping their forces around Canea, the Germans remained trapped until the end of the war, refusing to surrender to the Greek army, for fear of retaliation, they eventually surrendered to the British on 23 May 1945.[2]:313

The British involvement

Cretans and the Cretan resistance worked closely with the British, firstly when they aided the allied forces in escaping from Crete and secondly when they worked together on acts of sabotage while Crete was a launching pad for German operations in Africa. This involved the British agents who remained on Crete, such as Patrick Leigh Fermor, Tom Dunbabin, Sandy Rendel, Stephen Verney,[3] John Houseman, Xan Fielding, Dennis Ciclitira, Ralph Stockbridge and W. Stanley Moss. The New Zealander Dudley "Kiwi" Perkins became a legend for his courage, and after he was killed the Cretans kept his grave covered with flowers.[4]

The British formed a large number of isolated cells scattered throughout the mountains, with good communications, using runners, between them. Attached to these cells were Greeks who otherwise tended to have no involvement with the main Cretan resistance movement, but worked very closely with the British agents, such as Leigh Fermor’s runner George Psychoundakis and Kimonas Zografakis, who was a member of the British Force 133, the Allied espionage service in Greece,[2]:174 and involved in several operations.

Most cells had a radio for communicating with Egypt through which information could be passed and requests made for parachute drops of food, clothing, supplies and weapons. German troops constantly tried to locate the radio transmissions, which resulted in the requirement to change location regularly.

The British agents, working with local resistance, were responsible for some famous operations including the abduction of General Heinrich Kreipe led by Leigh Fermor and Moss, the battle of Trahili, the sabotage of Damasta led by Moss and the airfield sabotages of Heraklion and Kastelli.

Documentary

In 2005, a documentary was released titled The 11th Day: Crete 1941, which relates events of the Cretan resistance through various eyewitnesses.

References

- ↑ Described in detail in Michalis Kokolakis, Ανατολική Κρήτη. Κατοχή, αντίσταση, εμφύλιος (Athens, Alfeios, 1990).

- 1 2 3 4 5 Psychoundakis, George. The Cretan Runner. ISBN 0140273220.

- ↑ Slee, Colin (23 November 2013). "Special operations agent in wartime Crete who became an unconventional bishop". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ↑ Captain John Stanley (Royal Signals), who was also in Crete on special service, tells of the admiration the Cretans had for Perkins: ‘No other member of an Allied Mission was loved, respected and admired as was Kiwi (Perkins)’, from D. M. Davin, Crete (part of The Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–1945) (Wellington, Historical Publications Branch, 1953), p. 497. Accessed online at http://www.nzetc.org/tm/scholarly/tei-WH2Cret.html (accessed 21/01/2012).

External links

- German occupation of Crete (in German -- translate)

- German war crimes in Crete (in German -- translate)