Credibility thesis

| Economics |

|---|

_Per_Capita_in_2015.svg.png) |

|

|

| By application |

|

| Lists |

|

Credibility Thesis is a proposed heterodox theoretical framework for understanding how societal institutions come about and evolve. It purports that institutions emerge from intentional institution-building but never in the originally intended form.[1] Instead, institutional development is endogenous and spontaneously ordered and institutional persistence can be explained by their credibility,[2] which is provided by the function that particular institutions serve rather than their theoretical or ideological form. The Credibility Thesis can be applied to explain, for example, why purported institutional improvements do not take hold as part of structural adjustment programs, while other economies in the developing world deliver growth despite absence of clear and strong market mechanisms such as indisputable private property rights or clearly delineated and registered land tenure.

Postulates of Credibility Thesis

According to the Credibility Thesis, institutional persistence, meaning the survival and change of particular institutions through time is determined by the function of the institution and actors' expectations of the institution to play that function.

Changes in institutional arrangements, such as changes from informal land tenure and informal housing to a formalized real estate market or gradually declining prevalence of formal marriage or customary rights, are brought about by rule-making in a multi-actor playing field, where even the strongest actors cannot fully dictate institutional arrangements.

An institution that appears stable and unchanging over time can be said to exist in an equilibrium wherein actors’ conflicting interests on what form the institution should take are locked in a frozen conflict. For example, whether land holdings should be registered in a cadastre or if informal exchange of payment for use rights can suffice as confirmation of a land sale, constitute two possible land institution arrangements and either can be beneficial to different actors’ interests. That no actor perceives an immediate opportunity to change the arrangement to their advantage is a sign of the credibility of the assignment and the source of the equilibrium of institutional arrangement. However, disequilibrium characterises institutional arrangements and equilibrium is transitory and rare. In this aspect the Credibility Theory is juxtaposed to Structural functionalism, which is based on presupposed societal equilibrium.

A series of underlying postulates for the Credibility Thesis have been proposed: <<CITATION NEEDED>>

- Institutions are the resultant of unintentional development. Although actors have intentions, there is no agency that can externally design institutions, as actors’ actions are part of the same endogenous game. Institutions emerge as an unanticipated outcome of actors’ multitudinous interactions, in effect, are the result of an autonomous, Unintended Intentionality.

- Institutional change is driven by disequilibrium. Contrary to the notion that institutions settle around equilibrium, actors’ interactions are seen as an ever-changing and conflicting process in which stable status is never reached. One could see it as a “Progressive Disequilibrium” or institutional change as perpetual alteration, yet, with alternating speeds of change; sometimes, imperceptibly slow, sometimes, sudden and with shocks.

- Institutional Form is subordinate to Function. In other words, the use and disuse of institutions over time and space is what matters for understanding their role in development, not their appearance.[1]

Key concepts

| Term | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Credibility | Perceived social support of an institutional arrangement at a given time and space; a measure of individual actors’ aggregate perceptions of an institution as a jointly shared arrangement | |

| Institutional function | The use that a particular institutional arrangement can provide to actors. | In agricultural economy, land is primary asset from subsistence point of view: provides food security, enables utilization of family labour, and reduces vulnerability[3] The agricultural lease system in China functions as a social welfare net for the vast surplus of China’s rural labour.[1] |

| Empty institution | Institutional arrangements that emerge as compromises over sensitive political issues. The interests opposed to them ensure that they are established in such a way that they cannot achieve their aims. | Vilhelm Aubert observed that the Housemaid Law in Norway regulating the working conditions of domestic workers in Norway was on the books and technically being implemented but had not any effect.[4] |

| Non-credible institution | An institution that is being enforced by a powerful actor, complied by but not accepted by others. | Grazing ban implemented across grassland provinces in China is being implemented, but faces ongoing resistance.<<CITATION NEEDED>> |

| Progressive disequilibrium | “Instead of representing equilibrium (or even various equilibria on a trajectory) at which the interaction and power divergences of actors have led to a negotiated balance over the distribution of resources, the credibility thesis posits that credibility not necessarily equals a balance of power. In fact, one might argue that a steady status is never reached, as the notion assumes that conflict is present in any institutional arrangement or change.”[1] | |

| Institutional form | The categorical description of institutional arrangements. | Secure, private, formal as opposed to fuzzy, common, and customary property rights. |

Methodological approaches

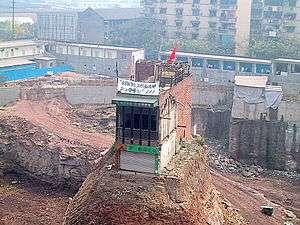

| Nail house | |

|

Conflicting interests over how institutions should be arranged drive institutional design such as the limits to refuse to vacate condemned property, such as this nail house in Chongqing in 2007. |

Given that all involved actors are constantly interested in changing institutional design, credibility cannot be measured by directly asking respondents whether they find an institution credible. Instead it has to be operationalized through proxies, such as the level of conflict that an institution generates; the extent of ‘institutional robustness’ expressed as a function of institutional lifespan and flexibility; the degree to which an institution facilitates or frustrates overall socio-economic, political and cultural change; and the extent to which an institution fulfills the functions it ought to perform in the eyes of social actors.” [5] Such opening of the black box of institutions possible using mixed methods to describe institutions in detail over time and space, which serves as an archaeology of institutions. The archaeology of institutions can be understood as detailed description of institutions, examining and comparing institutional function, credibility, perception, and conflict over time. An example of this, is the history of China's titling.[6] While predominantly applied to land-related institutions, this approach could be applied to analysis of other means of production.[7]

Emergence of the theory

The question of credibility first emerged along with concern about certain institutional interventions failing. In the mid-20th century Vilhelm Aubert noted that the Housemaid Law in Norway had been implemented but flaunted by all involved actors.[4] The concept of credibility was initially coined as an explanandum for the success and failure of Western monetary, anti-inflationary policies in the 1970s.[1] A concern for the credibility of policy emerged in the latter half of the 20th century in response to frequently observed failures of neoliberal structural adjustments in the developing world associated with the Washington Consensus. Institutional reform, such as privatization, failed to deliver the predicted economic growth, not because of lacking credible commitment on part of actors but due to the absence of endogenous credibility.[2]

In contrast, the growth of the Chinese economy despite lack of many institutions considered to be essential for economic growth indicated that institutional arrangements do not necessarily determine economic outcomes, and also at the same time economic development does not automatically lead to teleologically predetermined institutional forms.[8][9] This has been particularly striking in the case of real estate sector in China.[7] Thus it was suggested that research should embrace Lamarckian interpretation of functionalism and focus on the function or quality and performance measures of institutional performance rather than their form.[10]

The term “credibility thesis” was put forth by Peter Ho in 2014.[1] In a review of the Credibility Thesis, Delilah Griswold contended that “credibility is a powerful metric by which to understand and evaluate tenure systems. Importantly, understanding the credibility of a given institution requires analysis outside of theory and politics, analysis that is locally and temporally specific and multilayered.”[11]

See also

- Emergence

- Endogeneity

- Spontaneous order

- Lamarckism (the use and disuse of function determines the persistence, change or disappearance of institutions)

- Circular cumulative causation

- Form follows function (Architecture)

Related theories and theoretical bodies

- General disequilibrium

- Neo-Marxism, Heterodox economics, and Evolutionary economics

- Institutional economics

- Thorstein Veblen and John R. Commons

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ho, Peter (September 2014). "The 'credibility thesis' and its application to property rights: (In)Secure land tenure, conflict and social welfare in China". Land Use Policy. 40: 13–27. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2013.09.019. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- 1 2 Grabel, Ilene. "The political economy of 'policy credibility': the new-classical macroeconomics and the remaking of emerging economies". Cambridge Journal of Economics. 24 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1093/cje/24.1.1. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- ↑ Guhan, S (1994). "Social Security Options for Developing Countries". International Labour Review. 133 (35). Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- 1 2 Aubert, Vilhelm. "Some Social Functions of Legislation". Acta Sociologica. Sage Publications, Ltd. 10 (1/2): 1087–1118. doi:10.1080/03066150.2013.866553. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- ↑ Monique Kremer; Peter van Lieshout; Robert Went (2009). Doing Good Or Doing Better: Development Policies in a Globalizing World. Amsterdam University Press. pp. 186–. ISBN 978-90-8964-107-6.

- ↑ Ho, Peter (2015). "Myths of tenure security and titling: Endogenous, institutional change in China's development". Land Use Policy. 47: 352–364. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.04.008. ISSN 0264-8377.

- 1 2 Ho, Peter (19 December 2013). "In defense of endogenous, spontaneously ordered development: institutional functionalism and Chinese property rights". Journal of Peasant Studies. 40 (6): 1087–1118. doi:10.1080/03066150.2013.866553. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- ↑ L.P. "Autocracy or democracy?". economist.com. Retrieved 2015-06-18.

- ↑ OECD. "Issues paper on corruption and economic growth". oecd.org. Retrieved 2015-06-20.

- ↑ Aron, J. (2000). "Growth and Institutions: A Review of the Evidence". The World Bank Research Observer. 15 (1): 99–135. doi:10.1093/wbro/15.1.99. ISSN 0257-3032.

- ↑ Griswold, Delilah (9 July 2015). "With efficacy of property rights, function can be more important than form". Yale Environment Review. Retrieved 18 November 2015.