Handicap principle

The handicap principle is a hypothesis originally proposed in 1975 by Israeli biologist Amotz Zahavi to explain how evolution may lead to "honest" or reliable signaling between animals which have an obvious motivation to bluff or deceive each other.[1][2][3] The handicap principle suggests that reliable signals must be costly to the signaler, costing the signaler something that could not be afforded by an individual with less of a particular trait. For example, in the case of sexual selection, the theory suggests that animals of greater biological fitness signal this status through handicapping behaviour or morphology that effectively lowers this quality. The central idea is that sexually selected traits function like conspicuous consumption, signalling the ability to afford to squander a resource. Receivers know that the signal indicates quality because inferior quality signallers cannot afford to produce such wastefully extravagant signals.

The generality of the phenomenon is the matter of some debate and disagreement, and Zahavi's views on the scope and importance of handicaps in biology has not been accepted by the mainstream.[4] Nevertheless, the idea has been very influential,[5][6][7] with most researchers in the field believing that the theory explains some aspects of animal communication.

Handicap models

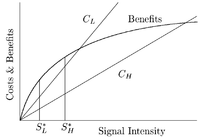

Though the handicap principle was initially controversial,[8][9][10][11]—John Maynard Smith being one notable early critic of Zahavi's ideas[12][13][14]—it has gained wider acceptance because it is supported by game theoretic models, most notably Alan Grafen's signalling game model.[15] Grafen's model is essentially a rediscovery of Michael Spence's job market signalling model,[16] where the signalled trait was conceived as a courting male's quality, signalled by investment in an extravagant trait—such as the peacock's tail—rather than an employee signalling their quality by way of a costly education. In both cases, it is the decreased cost to higher-quality signallers of producing increased signal that stabilizes the reliability of the signal (Fig. 2).

A series of papers by Thomas Getty shows that Grafen’s proof of the handicap principle depends on the critical simplifying assumption that signalers trade off costs for benefits in an additive fashion, the way humans invest money to increase income in the same currency.[17][18][19][20] This is illustrated in the figures to the right, from Johnstone 1997.[5] This assumption that costs and benefits trade off in an additive fashion is contested to be valid for the survival cost–reproduction benefit trade-off that is assumed to mediate the evolution of sexually selected signals. It can be reasoned that as fitness depends on the production of offspring, this is therefore a multiplicative function of reproductive success.[21]

Further formal game theoretical signalling models demonstrated the evolutionary stability of handicapped signals in nestlings' begging calls,[22] in predator-deterrent signals[23] and in threat-displays.[24][25] In the classic handicapped models of begging, all players are assumed to pay the same amount to produce a signal of a given level of intensity, but differ in the relative value of eliciting the desired response (donation) from the receiver (Fig. 3). The hungrier the baby bird, the more food is of value to it, and the higher the optimal signalling level (the louder its chirping).

Counter-examples to handicap models predate handicap models themselves. Models of signals (such as threat displays) without any handicapping costs show that conventional signalling may be evolutionarily stable in biological communication.[26] Analysis of some begging models also shows that, in addition to the handicapped outcomes, non-communication strategies are not only evolutionarily stable, but lead to higher payoffs for both players.[27][28] Mathematical analyses including Monte Carlo simulations suggest that costly traits used in mate choice by humans should be generally less common and more attractive to the other sex than non-costly traits.[29]

Generality and empirical examples

The theory predicts that a sexual ornament, or any other signal, must be costly if it is to accurately advertise a trait of relevance to an individual with conflicting interests. Typical examples of handicapped signals include bird songs, the peacock's tail, courtship dances, bowerbird's bowers, or even possibly jewellery and humor. Jared Diamond has proposed that certain risky human behaviours, such as bungee jumping, may be expressions of instincts that have evolved through the operation of the handicap principle. Zahavi has invoked the potlatch ceremony as a human example of the handicap principle in action. This interpretation of potlatch can be traced to Thorstein Veblen's use of the ceremony in his book Theory of the Leisure Class as an example of "conspicuous consumption".[30]

The handicap principle gains further support by providing interpretations for behaviours that fit into a single unifying gene-centered view of evolution and making earlier explanations based on group selection obsolete. A classic example is that of stotting in gazelles. This behaviour consists in the gazelle initially running slowly and jumping high when threatened by a predator such as a lion or cheetah. The explanation based on group selection was that such behaviour might be adapted to alerting other gazelle to a cheetah's presence or might be part of a collective behaviour pattern of the group of gazelle to confuse the cheetah. Instead, Zahavi proposed that each gazelle was communicating that it was a fitter individual than its fellows.[31] This may communicate to the cheetah to avoid chasing this fitter individual, or the message may be oriented toward the other gazelles, which would indicate its fitness to potential mates.

Immunocompetence handicaps

The theory of immunocompetence handicaps suggests that androgen-mediated traits accurately signal condition due to the immunosuppressive effects of androgens.[32] This immunosuppression may be either because testosterone alters the allocation of limited resources between the development of ornamental traits and other tissues, including the immune system,[33] or because heightened immune system activity has a propensity to launch autoimmune attacks against gametes, such that suppression of the immune system enhances fertility.[34] Healthy individuals can afford to suppress their immune system by raising their testosterone levels, which also augments secondary sexual traits and displays. A review of empirical studies into the various aspects of this theory found weak support.[35]

Examples

Directed at members of the same species

Amotz Zahavi studied in particular the Arabian babbler, a very social bird, with a life-length of 30 years, which was considered to have altruist behaviours. The helping-at-the-nest behavior often occurs among unrelated individuals, and therefore cannot be explained by kin selection. Zahavi reinterpreted these behaviours according to his signal theory and its correlative, the handicap principle. The altruistic act is costly to the donor, but may improve its attractiveness to potential mates. The evolution of this condition may be explained by competitive altruism.

The tail of a peacock makes the peacock more vulnerable to predators, and may therefore be a handicap. However, the message that the tail carries to the potential mate peahen may be 'I have survived in spite of this huge tail; hence I am fitter and more attractive than others'.

In the stalk-eyed fly, research by Patrice David has demonstrated that genetic variation underlies the response to environmental stress, such as variable food quality, of male sexual ornaments, such as the increased eye span, in the stalk-eyed fly.[36] David demonstrated that some male genotypes develop large eye spans under all conditions, whereas other genotypes progressively reduce eye spans as environmental conditions deteriorate. Several non-sexual traits, including female eye span and male and female wing length, also show condition-dependent expression, but their genetic response is entirely explained by scaling with body size. Unlike these characteristics, male eye span still reveals genetic variation in response to environmental stress after accounting for differences in body size. Thus, David inferred that these results strongly support the conclusion that female mate choice yields genetic benefits for offspring as eye span acts as a truthful indicator of male fitness. Eye span is therefore not only selected on the basis of attractiveness, but also because it demonstrates good genes in mates.[36]

An example in humans was suggested by Geoffrey Miller who expressed that Veblen goods such as luxury cars and other forms of conspicuous consumption are manifestations of the handicap principle, being used to advertise "fitness", in the form of wealth and status, to potential mates. Obesity, a sign of ability to procure or afford plenty of food, comes at the expense of health, agility, and in more advanced cases, even strength; in cultures that experience food scarcity, this exhibits "fitness" to the opposite sex and is also often associated with wealth. Recent cultural changes have altered this perception, particularly in western societies.

Directed at other species

The signal receiver need not be a conspecific of the sender, however. Signals may also be directed at predators, with the function of showing that pursuit will probably be unprofitable. Stotting, for instance, is a sort of hopping that certain gazelles do when they sight a predator. As this behavior gives no evident benefit and would seem to waste resources (diminishing the gazelle's head start if chased by the predator), it was a puzzle until handicap theory offered an explanation. According to this analysis, if the gazelle simply invests a little energy to show a lion that it has the fitness necessary to avoid capture, it may not have to evade the lion in an actual pursuit. The lion, faced with the demonstration of fitness, might decide that it will not catch this gazelle, and thus, avoid a wasted pursuit. The benefit to the gazelle is twofold. First, for the small amount of energy invested in the stotting, the gazelle might not have to expend the tremendous energy required to evade the lion. Second, if the lion is in fact capable of catching this gazelle, the gazelle's bluff leads to its survival that day.

Another example is provided by larks, some of which discourage merlin by sending a similar message: they sing while being chased, telling their predator that they will be difficult to capture.[37]

See also

- Aposematism

- Multiple sexual ornaments

- Signaling theory

- Signaling game

- Game theory

- Parasite-stress theory

References

- ↑ Zahavi, Amotz (1975). "Mate selection—a selection for a handicap". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 53 (1): 205–214. doi:10.1016/0022-5193(75)90111-3. PMID 1195756.

- ↑ Zahavi, Amotz (1977). "The cost of honesty (Further remarks on the handicap principle)". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 67 (3): 603–605. doi:10.1016/0022-5193(77)90061-3. PMID 904334.

- ↑ Zahavi, Amotz (1997). The handicap principle: a missing piece of Darwin's puzzle. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-510035-2.

- ↑ Review by Pomiankowski, Andrew; Iwasa, Y. (1998). "Handicap Signaling: Loud and True?". Evolution. 52 (3): 928–932. doi:10.2307/2411290. JSTOR 2411290.

- 1 2 3 4 Johnstone, R. A. (1995). "Sexual selection, honest advertisement and the handicap principle: reviewing the evidence". Biological Reviews. 70 (1): 1–65. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1995.tb01439.x. PMID 7718697.

- ↑ Johnstone, R. A. (1997). "The Evolution of Animal Signals". In Krebs, J. R.; Davies, N. B. Behavioural Ecology: An Evolutionary Approach (4th ed.). Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 155–178. ISBN 0865427313.

- ↑ Maynard Smith, J. and Harper, D. (2003) Animal Signals. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-852685-7.

- ↑ Davis, J. W. F.; O’Donald, P. (1976). "Sexual selection for a handicap: A critical analysis of Zahavi's model". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 57 (2): 345–354. doi:10.1016/0022-5193(76)90006-0.

- ↑ Eshel, I. (1978). "On the Handicap Principle—A Critical Defence". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 70 (2): 245–250. doi:10.1016/0022-5193(78)90350-8.

- ↑ Kirkpatrick, M. (1986). "The handicap mechanism of sexual selection does not work". American Naturalist. 127 (2): 222–240. doi:10.1086/284480. JSTOR 2461351.

- ↑ Pomiankowski, A. (1987). "Sexual selection: The handicap principle does work sometimes". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 231 (1262): 123–145. doi:10.1098/rspb.1987.0038.

- ↑ Maynard Smith, J. (1976). "Sexual selection and the handicap principle". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 57 (1): 239–242. doi:10.1016/S0022-5193(76)80016-1.

- ↑ Maynard Smith, J. (1978). "The Handicap Principle—A Comment". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 70 (2): 251–252. doi:10.1016/0022-5193(78)90351-X.

- ↑ Maynard Smith, J. (1985). "Mini Review: Sexual Selection, Handicaps and True Fitness". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 115 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1016/S0022-5193(85)80003-5.

- ↑ Grafen, A. (1990). "Biological signals as handicaps". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 144 (4): 517–546. doi:10.1016/S0022-5193(05)80088-8. PMID 2402153.

- ↑ Spence, A. M. (1973). "Job Market Signaling". Quarterly Journal of Economics. 87 (3): 355–374. doi:10.2307/1882010.

- ↑ Getty, T. (1998a). "Handicap signalling: when fecundity and viability do not add up". Anim. Behav. 56 (1): 127–130. doi:10.1006/anbe.1998.0744. PMID 9710469.

- ↑ Getty, T. (1998b). "Reliable signalling need not be a handicap". Anim. Behav. 56 (1): 253–255. doi:10.1006/anbe.1998.0748. PMID 9710484.

- ↑ Getty, T. (2002). "Signaling health versus parasites". Am. Nat. 159 (4): 363–371. doi:10.1086/338992. JSTOR 338992. PMID 18707421.

- ↑ Getty, T. (2006). "Sexually selected signals are not similar to sports handicaps". Trends Ecol. & Evol. 21 (2): 83–88. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2005.10.016.

- ↑ Nur, N.; Hasson, O. (1984). "Phenotypic plasticity and the handicap principle". J. Theor. Biol. 110 (2): 275–297. doi:10.1016/S0022-5193(84)80059-4.

- ↑ Godfray, H. C. J. (1991). "Signalling of need by offspring to their parents". Nature. 352 (6333): 328–330. doi:10.1038/352328a0.

- ↑ Yachi, S. (1995). "How can honest signalling evolve? The role of the handicap principle". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 262 (1365): 283–288. doi:10.1098/rspb.1995.0207.

- ↑ Adams, E. S.; Mesterton-Gibbons, M. (1995). "The cost of threat displays and the stability of deceptive communication". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 175 (4): 405–421. doi:10.1006/jtbi.1995.0151.

- ↑ Kim, Y-G. (1995). "Status signalling games in animal contests". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 176 (2): 221–231. doi:10.1006/jtbi.1995.0193. PMID 7475112.

- ↑ Enquist, M. (1985). "Communication during aggressive interactions with particular reference to variation in choice of behaviour". Animal Behaviour. 33 (4): 1152–1161. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(85)80175-5.

- ↑ Rodriguez-Girones, M. A.; Cotton, P. A.; Kacelnik, A. (1996). "The evolution of begging: signaling and sibling competition". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 93 (25): 14637–14641. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.25.14637.

- ↑ Lachmann, M.; Bergstrom, C. T. (1998). "Signalling among relatives. II. Beyond the tower of babel". Theoretical Population Biology. 54 (2): 146–160. doi:10.1006/tpbi.1997.1372. PMID 9733656.

- ↑ Kock, N. (2011). "A mathematical analysis of the evolution of human mate choice traits: Implications for evolutionary psychologists" (PDF). Journal of Evolutionary Psychology. 9 (3): 219–247. doi:10.1556/jep.9.2011.3.1.

- ↑ Bliege Bird, R.; Smith, E. A. (2005). "Signalling theory, strategic interaction, and symbolic capital". Current Anthropology. 46 (2): 221–248. doi:10.1086/427115. JSTOR 427115.

- ↑ Amotz Zahavi; Avishag Zahavi (1997). Jumping to Bold Conclusions A Review of The Handicap Principle: A Missing Piece of Darwin's Puzzle (PDF). Oxford University Press. p. 286.

- ↑ Folstad, I.; Karter, A. K. (1992). "Parasites, bright males, and the immunocompetence handicap". American Naturalist. 139 (3): 603–622. doi:10.1086/285346. JSTOR 2462500.

- ↑ Wedekind, C.; Folstad, I. (1994). "Adaptive or non-adaptive immunosuppression by sex hormones?". American Naturalist. 143 (5): 936–938. doi:10.1086/285641. JSTOR 2462885.

- ↑ Folstad, I.; Skarstein, F. (1996). "Is male germ line control creating avenues for female choice?". Behavioral Ecology. 8 (1): 109–112. doi:10.1093/beheco/8.1.109.

- ↑ Roberts, M. L.; Buchanan, K. L.; Evans, M. R. (2004). "Testing the immunocompetence handicap hypothesis: a review of the evidence". Animal Behaviour. 68 (2): 227–239. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2004.05.001.

- 1 2 P. David; T. Bjorksten; K. Fowler; A. Pomiankowski (2000). "Condition-dependent signalling of genetic variation in stalk-eyed flies". Nature. 406 (6792): 186–188. doi:10.1038/35018079. PMID 10910358.

- ↑ For footage of this, see Attenborough, D. (1990) The Trials of Life, Episode 10. BBC.

External links

- Honest Signalling Theory: A Basic Introduction. By Carl T. Bergstrom, University of Washington, 2006.