Cosmetics

Cosmetics, also known as make-up, are substances or products used to enhance the appearance or fragrance of the body. Many cosmetics are designed for use of applying to the face and hair. In the 21st century, women generally use more cosmetics than men. They are generally mixtures of chemical compounds; some being derived from natural sources (such as coconut oil), and some being synthetics.[1] Common cosmetics include lipstick, mascara, eye shadow, foundation, rouge, skin cleansers and skin lotions, shampoo, hairstyling products (gel, hair spray, etc.), perfume and cologne.

In the U.S., the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which regulates cosmetics,[2] defines cosmetics as "intended to be applied to the human body for cleansing, beautifying, promoting attractiveness, or altering the appearance without affecting the body's structure or functions". This broad definition includes any material intended for use as a component of a cosmetic product. The FDA specifically excludes soap from this category.[3]

Etymology

The word cosmetics derives from the Greek κοσμητικὴ τέχνη (kosmetikē tekhnē), meaning "technique of dress and ornament", from κοσμητικός (kosmētikos), "skilled in ordering or arranging"[4] and that from κόσμος (kosmos), meaning amongst others "order" and "ornament".[5]

History

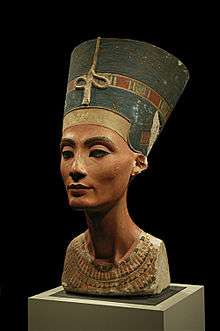

Ancient Sumerian men and women were possibly the first to invent and wear lipstick, about 5,000 years ago.[6] They crushed gemstones and used them to decorate their faces, mainly on the lips and around the eyes.[7] Also around 3000 BC to 1500 BC, women in the ancient Indus Valley Civilization applied red tinted lipstick to their lips for face decoration.[8] Ancient Egyptians extracted red dye from fucus-algin, 0.01% iodine, and some bromine mannite, but this dye resulted in serious illness. Lipsticks with shimmering effects were initially made using a pearlescent substance found in fish scales.[9] Six thousand year old relics of the hollowed out tombs of the Ancient Egyptian pharaohs are discovered.[10] According to one source, early major developments include:[1]

- Kohl used by ancient Egypt as a protective of the eye kohl

- Castor oil used by ancient Egypt as a protective balm.

- Skin creams made of beeswax, olive oil, and rose water, described by Romans.

- Vaseline and lanolin in the nineteenth century.

The Ancient Greeks also used cosmetics[11][12] as the Ancient Romans did. Cosmetics are mentioned in the Old Testament, such as in 2 Kings 9:30, where Jezebel painted her eyelids—approximately 840 BC—and in the book of Esther, where beauty treatments are described.

One of the most popular traditional Chinese medicines is the fungus Tremella fuciformis, used as a beauty product by women in China and Japan. The fungus reportedly increases moisture retention in the skin and prevents senile degradation of micro-blood vessels in the skin, reducing wrinkles and smoothing fine lines. Other anti-ageing effects come from increasing the presence of superoxide dismutase in the brain and liver; it is an enzyme that acts as a potent antioxidant throughout the body, particularly in the skin.[13]

Cosmetic use was frowned upon at many points in Western history. For example, in the 19th century, Queen Victoria publicly declared make-up improper, vulgar, and acceptable only for use by actors.[14]

During the sixteenth century, the personal attributes of the women who used make-up created a demand for the product among the upper class.[15]

As of 2016, the world's largest cosmetics company is L'Oréal, which was founded by Eugène Schueller in 1909 as the French Harmless Hair Colouring Company (now owned by Liliane Bettencourt 26% and Nestlé 28%; the remaining 46% is traded publicly). The market was developed in the US during the 1910s by Elizabeth Arden, Helena Rubinstein, and Max Factor. These firms were joined by Revlon just before World War II and Estée Lauder just after.

During the 18th century, there was a high number of incidences of lead-poisoning because of the fashion for red and white lead makeup and powder. This led to swelling and inflammation of the eyes, attacked tooth enamel, and caused skin to blacken. Heavy use was known to lead to death.

Although modern make-up has been traditionally used mainly by women, an increasing number of men are using cosmetics usually associated to women to enhance or cover their own facial features such as blemishes, dark circles, and so on. Concealer is commonly used by men. Cosmetics brands release products especially tailored for men, and men are increasingly using them.[16]

Types

Cosmetics are intended to be applied externally. They include but are not limited to products that can be applied to the face: skin-care creams, lipsticks, eye and facial makeup, towelettes, and colored contact lenses; to the body: deodorants, lotions, powders, perfumes, baby products, bath oils, bubble baths, bath salts, and body butters; to the hands/nails: fingernail and toe nail polish, and hand sanitizer; to the hair: permanent chemicals, hair colors, hair sprays, and gels.

A subset of cosmetics is called "make-up", refers primarily to products containing color pigments that are intended to alter the user’s appearance. Manufacturers may distinguish between "decorative" and "care" cosmetics.

Cosmetics that are meant to be used on the face and eye area are usually applied with a brush, a makeup sponge, or the fingertips.

Most cosmetics are distinguished by the area of the body intended for application.

- Primer comes in formulas to suit individual skin conditions. Most are meant to reduce the appearance of pore size, prolong the wear of makeup, and allow for a smoother application of makeup. Primers are applied before foundation or eyeshadows depending on where the primer is to be applied.

- Lipstick, lip gloss, lip liner, lip plumper, lip balm, lip stain, lip conditioner, lip primer, lip boosters, and lip butters:[2] Lipsticks are intended to add color and texture to the lips and often come in a wide range of colors, as well as finishes such as matte, satin, and lustre. Lip stains have a water or gel base and may contain alcohol to help the product stay on leaving a matte look. They temporarily saturate the lips with a dye. Usually designed to be waterproof, the product may come with an applicator brush, rollerball, or could be applied with a finger. Lip glosses are intended to add shine to the lips and may add a tint of color, as well as being scented or flavored for a pop of fun. Lip balms are most often used to moisturize, tint, and protect the lips. Some brands contain sunscreen.

- Concealer makeup covers imperfections of the skin. Concealer is often used for any extra coverage needed to cover blemishes, undereye circles, and other imperfections. Concealer is often thicker and more solid than foundation, and provides longer lasting, more detailed coverage. Some formulations are intended only for the eye or only for the face. This product can also be used for contouring the face like ones nose, cheekbones, and jaw line to add a more defined look to the total face.

- Foundation is used to smooth out the face and cover spots, acne, blemishes, or uneven skin coloration. These are sold in a liquid, cream, or powder, or most recently a mousse. Foundation provides coverage from sheer to matt to dewey or full.[2] Foundation primer can be applied before or after foundation to obtain a smoother finish. Some primers come in powder or liquid form to be applied before foundation as a base, while other primers come as a spray to be applied after the foundation to set the make-up and help it last longer throughout the day.

- Face powder sets the foundation, giving it a matte finish, and to conceal small flaws or blemishes. It can also be used to bake the foundation, so that it stays on longer. Tinted face powders may be worn alone as a light foundation so that the full face does not look as caked-up as it could.

- Rouge, blush, or blusher is cheek coloring to bring out the color in the cheeks and make the cheekbones appear more defined. Rouge comes in powder, cream, and liquid forms. Different blush colors are used to compliment different skin tones.[2]

- Contour powders and creams are used to define the face. They can give the illusion of a slimmer face or to modify a face shape in other desired ways. Usually a few shades darker than the skin tone and matte in finish, contour products create the illusion of depth. A darker-toned foundation/concealer can be used instead of contour products for the same purpose.

- Highlight, used to draw attention to the high points of the face as well as to add glow, comes in liquid, cream, and powder forms. It often contains a substance to provide shimmer. Alternatively, a lighter-toned foundation/concealer can be used.

- Bronzer gives skin a bit of color by adding a golden or bronze glow and highlighting the cheekbones, as well as being used for contouring. Bronzer is considered to be more of a natural look and can be used for an everyday wear. Bronzer enhances the color of the face while adding more of a shimmery look.[2] It comes in either matte, semi matte/satin, or shimmer finishes.

- Mascara is used to darken, lengthen, thicken, or draw attention to the eyelashes. It is available in various colors. Some mascaras include glitter flecks. There are many formulas, including waterproof versions for those prone to allergies or sudden tears. It is often used after an eyelash curler and mascara primer.[2] Many mascaras have components to help lashes appear longer and thicker.

- Eye Shadow is a pigmented powder/cream or substance used to accentuate the eye area, traditionally on above and under the eyelids. Many colours may be used at once and blended together to create different effects. This is conventionally applied with a range of eyeshadow brushes though it isn't uncommon for alternative methods of application to be used. [17]

- Eye liner is used to enhance and elongate the apparent size or depth of the eye. For example, white eyeliner on the waterline and inner corners of the eye makes the eyes look bigger and more awake. It can come in the form of a pencil, a gel, or a liquid and can be found in almost any color.

- Eyebrow pencils, creams, waxes, gels, and powders are used to color, fill in, and define the brows.[2]

- Nail polish is used to color the fingernails and toenails.[2] Transparent, colorless versions may strengthen nails or as a top or base coat to protect the nail or polish.

- Setting spray is used as the last step in the process of applying makeup. It keeps applied makeup intact for long periods. An alternative to setting spray is setting powder, which may be either pigmented or translucent. Both of these products are claimed to keep makeup from absorbing into the skin or melting off.

- False eyelashes are used when exaggerated eyelashes are desired. Their basic design usually consists of human hair or synthetic materials attached to a thin cloth-like band, which is applied with glue to the lashline. Designs vary in length and color. Rhinestones, gems, and even feathers and lace occur on some false eyelash designs.

- Contouring is designed to give shape to an area of the face. The aim is to enhance the natural shading on your face to give the illusion of a more defined facial structure which can be altered to preference. Brighter skin coloured makeup products are used to 'highlight' areas which we want to draw attention to or to be caught in the light. Whereas darker shades are used to create a shadow. These light and dark tones are blended on the skin to create the illusion of a more definite face shape. It can be achieved using a "contour palette" - which can be either cream or powder.

Cosmetics can be also described by the physical composition of the product. Cosmetics can be liquid or cream emulsions; powders, both pressed and loose; dispersions; and anhydrous creams or sticks.

Makeup remover is a product used to remove the makeup products applied on the skin. It cleans the skin before other procedures, like applying bedtime lotion.

Products

Cleansing is a standard step in skin care routines. Skin cleaning include some or all of these steps or cosmetics:

- Toners are used after cleansing the skin to freshen it up, boost the appearance of one's complexion, and remove any traces of cleanser, mask, or makeup, as well to help restore the skin's natural pH. They are usually applied to a cotton pad and wiped over the skin, but can be sprayed onto the skin from a spray bottle. Toners typically contain alcohol, water, and herbal extracts or other chemicals depending on skin type whether oily, dry, or combination. Toners containing alcohol are quite astringent, and usually targeted at oily skins. Dry or normal skin should be treated with alcohol-free toners. Witch hazel solution is a popular toner for all skin types, but many other products are available. Many toners contain salicylic acid and/or benzoyl peroxide. These types of toners are targeted at oily skin types, as well as acne-prone skin.

- Facial masks are treatments applied to the skin and then removed. Typically, they are applied to a dry, cleansed face, avoiding the eyes and lips.

- Clay-based masks use kaolin clay or fuller's earth to transport essential oils and chemicals to the skin, and are typically left on until completely dry. As the clay dries, it absorbs excess oil and dirt from the surface of the skin and may help to clear blocked pores or draw comedones to the surface. Because of its drying actions, clay-based masks should only be used on oily skins.

- Peel masks are typically gel-like in consistency, and contain acids or exfoliating agents to help exfoliate the skin, along with other ingredients to hydrate, discourage wrinkles, or treat uneven skin tone. They are left on to dry and then gently peeled off. They should be avoided by people with dry skin, as they tend to be very drying.

- Sheet masks are a relatively new product that are becoming extremely popular in Asia. Sheet masks consist of a thin cotton or fiber sheet with holes cut out for the eyes and lips and cut to fit the contours of the face, onto which serums and skin treatments are brushed in a thin layer; the sheets may be soaked in the treatment. Masks are available to suit almost all skin types and skin complaints. Sheet masks are quicker, less messy, and require no specialized knowledge or equipment for their use compared to other types of face masks, but they may be difficult to find and purchase outside Asia.

- Exfoliants are products that help slough off dry, dead skin cells to improve the skin's appearance. This is achieved either by using mild acids or other chemicals to loosen old skin cells, or abrasive substances to physically scrub them off. Exfoliation can even out patches of rough skin, improve circulation to the skin, clear blocked pores to discourage acne and improve the appearance and healing of scars.

- Chemical exfoliants may include citric acid (from citrus fruits), acetic acid (from vinegar), malic acid (from fruit), glycolic acid, lactic acid, or salicylic acid. They may be liquids or gels, and may or may not contain an abrasive to remove old skin cells afterwards.

- Abrasive exfoliants include gels, creams or lotions, as well as physical objects. Loofahs, microfiber cloths, natural sponges, or brushes may be used to exfoliate skin, simply by rubbing them over the face in a circular motion. Gels, creams, or lotions may contain an acid to encourage dead skin cells to loosen, and an abrasive such as microbeads, sea salt, sugar, ground nut shells, rice bran, or ground apricot kernels to scrub the dead cells off the skin. Salt and sugar scrubs tend to be the harshest, while scrubs containing beads or rice bran are typically very gentle.

- Moisturizers are creams or lotions that hydrate the skin and help it to retain moisture; they may contain essential oils, herbal extracts, or chemicals to assist with oil control or reducing irritation. Night creams are typically more hydrating than day creams, but may be too thick or heavy to wear during the day, hence their name. Tinted moisturizers contain a small amount of foundation, which can provide light coverage for minor blemishes or to even out skin tones. They are usually applied with the fingertips or a cotton pad to the entire face, avoiding the lips and area around the eyes. Eyes require a different kind of moisturizer compared with the rest of the face. The skin around the eyes is extremely thin and sensitive, and is often the first area to show signs of aging. Eye creams are typically very light lotions or gels, and are usually very gentle; some may contain ingredients such as caffeine or Vitamin K to reduce puffiness and dark circles under the eyes. Eye creams or gels should be applied over the entire eye area with a finger, using a patting motion.

Other products

There are two categories of personal care products. The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act defines cosmetics as products intended to cleanse or beautify (for instance, shampoos and lipstick). A separate category exists for medications, which are intended to diagnose, cure, mitigate, treat, or prevent disease, or to affect the structure or function of the body (for instance, sunscreens and acne creams). Some products, such as moisturizing sunscreens and anti-dandruff shampoos, are regulated within both categories.[18][19]

Ingredients

A variety of organic compounds and inorganic compounds comprise typical cosmetics. Typical organic compounds are modified natural oils and fats as well as a variety of petrochemically derived agents. Inorganic compounds are processed minerals such as iron oxides, talc, and zinc oxide. The oxides of zinc and iron are classified as pigments, i.e. colorants that have no solubility in solvents.

Natural

Handmade and certified organic products are becoming more mainstream, due to the fact that certain chemicals in some skincare products may be harmful if absorbed through the skin. Products claimed to be organic should, in the U.S., be certified "USDA Organic".[20]

Mineral

The term "mineral makeup" applies to a category of face makeup, including foundation, eye shadow, blush, and bronzer, made with loose, dry mineral powders. These powders are often mixed with oil-water emulsions. Lipsticks, liquid foundations, and other liquid cosmetics, as well as compressed makeups such as eye shadow and blush in compacts, are often called mineral makeup if they have the same primary ingredients as dry mineral makeups. However, liquid makeups must contain preservatives and compressed makeups must contain binders, which dry mineral makeups do not. Mineral makeup usually does not contain synthetic fragrances, preservatives, parabens, mineral oil, and chemical dyes. For this reason, dermatologists may consider mineral makeup to be gentler to the skin than makeup that contains those ingredients.[21] Some minerals are nacreous or pearlescent, giving the skin a shining or sparking appearance. One example is bismuth oxychloride.[1] There are various mineral-based makeup brands, including: Bare Minerals, Tarte, Bobbi Brown, and Stila.

Benefits of mineral-based makeup

Although the chemical constituent of cosmetics sometimes cause concerns, some chemicals are widely seen as beneficial. Titanium dioxide, found in sunscreens, and zinc oxide have anti-inflammatory properties, mineral makeups with those ingredients can have a calming effect on the skin, which is particularly important for those who suffer from inflammatory problems such as rosacea. Zinc oxide is anti-microbial,[22] so mineral makeups can be beneficial for people with acne.

Mineral makeup is noncomedogenic (as long as it does not contain talc) and offers a mild amount of sun protection (because of the titanium dioxide and zinc oxide).[23]

Because they do not contain liquid ingredients, mineral makeups have long shelf-lives.

Cosmetic Packaging

The term cosmetic packaging is used for primary packaging and secondary packaging of cosmetic products.[24][25]

Primary packaging, also called cosmetic container, is housing the cosmetic product. It is in direct contact with the cosmetic product. Secondary packaging is the outer wrapping of one or several cosmetic container(s). An important difference between primary and secondary packaging is that any information that is necessary to clarify the safety of the product must appear on the primary package. Otherwise, much of the required information can appear on just the secondary packaging. [26][27][28]

Cosmetic packaging is standardized by the ISO 22715, set by the International Organization for Standardization[25][29] and regulated by national or regional regulations such as those issued by the EU or the FDA. Marketers and manufacturers of cosmetic products must be compliant to these regulations to be able to market their cosmetic products in the corresponding areas of jurisdiction.[30]

Industry

The manufacture of cosmetics is dominated by a small number of multinational corporations that originated in the early 20th century, but the distribution and sale of cosmetics is spread among a wide range of businesses. The worlds largest cosmetic companies are L'Oréal, Procter & Gamble, Unilever, Shiseido, and Estée Lauder.[31] In 2005, the market volume of the cosmetics industry in the US, Europe, and Japan was about EUR 70B/y.[1] In Germany, the cosmetic industry generated €12.6 billion of retail sales in 2008,[32] which makes the German cosmetic industry the third largest in the world, after Japan and the United States. German exports of cosmetics reached €5.8 billion in 2008, whereas imports of cosmetics totaled €3 billion.[32]

The worldwide cosmetics and perfume industry currently generates an estimated annual turnover of US$170 billion (according to Eurostaf – May 2007). Europe is the leading market, representing approximately €63 billion, while sales in France reached €6.5 billion in 2006, according to FIPAR (Fédération des Industries de la Parfumerie – the French federation for the perfume industry).[33] France is another country in which the cosmetic industry plays an important role, both nationally and internationally. According to data from 2008, the cosmetic industry has grown constantly in France for 40 consecutive years. In 2006, this industrial sector reached a record level of €6.5 billion. Famous cosmetic brands produced in France include Vichy, Yves Saint Laurent, Yves Rocher, and many others.

The Italian cosmetic industry is also an important player in the European cosmetic market. Although not as large as in other European countries, the cosmetic industry in Italy was estimated to reach €9 billion in 2007.[34] The Italian cosmetic industry is dominated by hair and body products and not makeup as in many other European countries. In Italy, hair and body products make up approximately 30% of the cosmetic market. Makeup and facial care, however, are the most common cosmetic products exported to the United States.

Due to the popularity of cosmetics, especially fragrances and perfumes, many designers who are not necessarily involved in the cosmetic industry came up with perfumes carrying their names. Moreover, some actors and singers (such as Celine Dion) have their own perfume line. Designer perfumes are, like any other designer products, the most expensive in the industry as the consumer pays for the product and the brand. Famous Italian fragrances are produced by Giorgio Armani, Dolce & Gabbana, and others.

Procter & Gamble, which sells CoverGirl and Dolce & Gabbana makeup, funded a study[35] concluding that makeup makes women seem more competent.[36] Due to the source of funding, the quality of this Boston University study is questioned.

Controversy

During the 20th century, the popularity of cosmetics increased rapidly.[37] Cosmetics are increasingly used by girls at a young age, especially in the United States.[38] Because of the fast-decreasing age of make-up users, many companies, from high-street brands like Rimmel to higher-end products like Estee Lauder, cater to this expanding market by introducing flavored lipsticks and glosses, cosmetics packaged in glittery and sparkly packaging, and marketing and advertising using young models.[39] The social consequences of younger and younger cosmetics use has had much attention in the media over the last few years.

Criticism of cosmetics has come from a wide variety of sources including some feminists,[40] religious groups, animal rights activists, authors, and public interest groups.

Safety

In the United States: "Under the law, cosmetic products and ingredients do not need FDA premarket approval."[41] The EU and other regulatory agencies around the world have more stringent regulations.[42] The FDA does not have to approve or review cosmetics, or what goes in them, before they are sold to the consumers. The FDA only regulates against some colors that can be used in the cosmetics and hair dyes. The cosmetic companies do not have to report any injuries from the products; they also only have voluntary recalls of products.[2]

There has been a marketing trend towards the sale of cosmetics lacking controversial ingredients, especially those derived from petroleum, sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS), and parabens.[43] Numerous reports have raised concern over the safety of a few surfactants, including 2-Butoxyethanol. SLS causes a number of skin problems, including dermatitis.[44][45][46][47][48]

Parabens can cause skin irritation and contact dermatitis in individuals with paraben allergies, a small percentage of the general population.[49] Animal experiments have shown that parabens have a weak estrogenic activity, acting as xenoestrogens.[50]

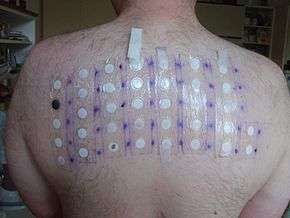

Synthetic fragrances are widely used in consumer products. Studies concluded from patch testing show synthetic fragrances are made of many ingredients which cause allergic reactions.[51]

Balsam of Peru was the main recommended marker for perfume allergy before 1977, which is still advised. The presence of Balsam of Peru in a cosmetic will be denoted by the INCI term Myroxylon pereirae.[52][53] In some instances, Balsam of Peru is listed on the ingredient label of a product by one of its various names, but it may not be required to be listed by its name by mandatory labeling conventions (in fragrances, for example, it may simply be covered by an ingredient listing of "fragrance").[53][54][55][56]

Cosmetics companies make pseudo-scientific claims about their products which are misleading or unsupported by scientific evidence.[57][58]

Animal testing

Cosmetics testing on animals is particularly controversial. Such tests involve general toxicity, eye and skin irritancy, phototoxicity (toxicity triggered by ultraviolet light), and mutagenicity.[59]

Cosmetics testing is banned in the Netherlands, Belgium, and the UK, and in 2002, after 13 years of discussion, the European Union (EU) agreed to phase in a near-total ban on the sale of animal-tested cosmetics throughout the EU from 2009, and to ban all cosmetics-related animal testing. France, which is home to the world's largest cosmetics company, L'Oréal, has protested the proposed ban by lodging a case at the European Court of Justice in Luxembourg, asking that the ban be quashed.[60] The ban is also opposed by the European Federation for Cosmetics Ingredients, which represents 70 companies in Switzerland, Belgium, France, Germany, and Italy.[60]

Legislation

Europe

In the European Union, the manufacture, labelling, and supply of cosmetics and personal care products are Regulated by Regulation EC 1223/2009.[61] It applies to all the countries of the EU as well as Iceland, Norway, and Switzerland. This regulation applies to single-person companies making or importing just one product as well as to large multinationals. Manufacturers and importers of cosmetic products must comply with the applicable regulations in order to sell their products in the EU. In this industry, it is common fall back on a suitably qualified person, such as an independent third party inspection and testing company, to verify the cosmetics’ compliance with the requirements of applicable cosmetic regulations and other relevant legislation, including REACH, GMP, hazardous substances, etc.[62]

In the European Union, the circulation of cosmetic products and their safety has been a subject of legislation since 1976. One of the newest improvement of the regulation concerning cosmetic industry is a result of the ban animal testing. Testing cosmetic products on animals has been illegal in the European Union since September 2004, and testing the separate ingredients of such products on animals is also prohibited by law, since March 2009 for some endpoints and full since 2013.[63]

Cosmetic regulations in Europe are often updated to follow the trends of innovations and new technologies while ensuring product safety. For instance, all annexes of the Regulation 1223/2009 were aimed to address potential risks to human health. Under the EU cosmetic regulation, manufacturers, retailers, and importers of cosmetics in Europe will be designated as “Responsible Person”.[64] This new status implies that the responsible person has the legal liability to ensure that the cosmetics and brands they manufacture or sell comply with the current cosmetic regulations and norms. The responsible person is also responsible of the documents contained in the Product Information File (PIF), a list of product information including data such as Cosmetic Product Safety Report, product description, GMP statement, or product function.

United States

In 1938, the U.S. passed the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act authorizing the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to oversee safety via legislation in the cosmetic industry and its aspects in the United States.[65][66] The FDA joined with 13 other federal agencies in forming the Interagency Coordinating Committee on the Validation of Alternative Methods (ICCVAM) in 1997, which is an attempt to ban animal testing and find other methods to test cosmetic products.[67]

Brazil

ANVISA (Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária, Brazilian Health Surveillance Agency) is the regulatory body responsible for cosmetic legislation and directives in the country. The rules apply to manufacturers, importers, and retailers of cosmetics in Brazil, and most of them have been harmonized so they can apply to the entire Mercosur.

The current legislation restricts the use of certain substances such as pyrogallol, formaldehyde, or paraformaldehyde and bans the use of others such as lead acetate in cosmetic products. All restricted and forbidden substances and products are listed in the regulation RDC 16/11 and RDC 162, 09/11/01.

More recently, a new cosmetic Technical Regulation (RDC 15/2013) was set up to establish a list of authorized and restricted substances for cosmetic use, used in products such as hair dyes, nail hardeners, or used as product preservatives.

Most Brazilian regulations are optimized, harmonized, or adapted in order to be applicable and extended to the entire Mercosur economic zone.

International

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) published new guidelines on the safe manufacturing of cosmetic products under a Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) regime. Regulators in several countries and regions have adopted this standard, ISO 22716:2007, effectively replacing existing guidance and standards. ISO 22716 provides a comprehensive approach for a quality management system for those engaged in the manufacturing, packaging, testing, storage, and transportation of cosmetic end products. The standard deals with all aspects of the supply chain, from the early delivery of raw materials and components until the shipment of the final product to the consumer.

The standard is based on other quality management systems, ensuring smooth integration with such systems as ISO 9001 or the British Retail Consortium (BRC) standard for consumer products. Therefore, it combines the benefits of GMP, linking cosmetic product safety with overall business improvement tools that enable organisations to meet global consumer demand for cosmetic product safety certification.[68]

In July 2012, since microbial contamination is one of the greatest concerns regarding the quality of cosmetic products, the ISO has introduced a new standard for evaluating the antimicrobial protection of a cosmetic product by preservation efficacy testing and microbiological risk assessment.

Careers

An account executive is responsible for visiting department and specialty stores with counter sales of cosmetics. They explain new products and "gifts with purchase" arrangements (free items given out upon purchase of cosmetics items costing over some set amount).

A beauty adviser provides product advice based on the client's skin care and makeup requirements. Beauty advisers can be certified by an Anti-Aging Beauty Institute.

A cosmetician is a professional who provides facial and body treatments for clients. The term cosmetologist is sometimes used interchangeably with this term, but the former most commonly refers to a certified professional. A freelance make-up artist provides clients with beauty advice and cosmetics assistance. They are usually paid by the hour by a cosmetic company; however, they sometimes work independently.

Professionals in cosmetics marketing careers manage research focus groups, promote the desired brand image, and provide other marketing services (sales forecasting, allocation to retailers, etc.).

Many involved within the cosmetics industry often specialize in a certain area of cosmetics such as special effects makeup or makeup techniques specific to the film, media, and fashion sectors.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Schneider, Günther et al (2005). "Skin Cosmetics" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a24_219

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Cosmetics and Your Health – FAQs". Womenshealth.gov. November 2004. Archived from the original on 2013-03-12.

- ↑ Lewis, Carol (2000). "Clearing up Cosmetic Confusion." FDA Consumer Magazine

- ↑ Liddell, Henry George and Scott, Robert. κοσμητικός in A Greek-English Lexicon

- ↑ Liddell, Henry George and Scott, Robert. κόσμος in A Greek-English Lexicon

- ↑ Schaffer, Sarah (2006), Reading Our Lips: The History of Lipstick Regulation in Western Seats of Power, Digital Access to Scholarship at Harvard, retrieved 2014-06-05

- ↑ "The Slightly Gross Origins of Lipstick". InventorSpot. Retrieved 2010-02-09.

- ↑ Williams, Yona . Ancient Indus Valley: Food, Clothing & Transportation. unexplainable.net

- ↑ Johnson, Rita. "What's That Stuff?". Chemical and Engineering News. 77 (28): 31.

- ↑ History of Cosmetics. historyofcosmetics.net

- ↑ Adkins, Lesley and Adkins, Roy A. (1998) Handbook to life in Ancient Greece, Oxford University Press

- ↑ Burlando, Bruno; Verotta, Luisella; Cornara, Laura and Bottini-Massa, Elisa (2010) Herbal Principles in Cosmetics, CRC Press

- ↑ Reshetnikov SV, Wasser SP, Duckman I, Tsukor K (2000). "Medicinal value of the genus Tremella Pers. (Heterobasidiomycetes) (review)". International Journal of Medicinal Mushrooms. 2 (3): 345–67. doi:10.1615/IntJMedMushr.v2.i3.10.

- ↑ Pallingston, J (1998). Lipstick: A Celebration of the World's Favorite Cosmetic. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-19914-7.

- ↑ Angeloglou, Maggie. The History of Make-up. First ed. Great Britain: The Macmillan Company, 1970. 41–42. Print.

- ↑ "FDA Authority Over Cosmetics". Cfsan.fda.gov. Retrieved 2011-10-23.

- ↑ "eyeshadow - definition of eyeshadow in English | Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries | English. Retrieved 2016-11-30.

- ↑ Kessler R. More than Cosmetic Changes: Taking Stock of Personal Care Product Safety. Environ Health Perspect; DOI:10.1289/ehp.123-A120

- ↑ FDA. Cosmetics: Guidance & Regulation; Laws & Regulations. Prohibited & Restricted Ingredients. [website]. U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD. Updated 26 January 2015.

- ↑ Singer, Natasha (2007-11-01). "Natural, Organic Beauty". New York Times.

- ↑ "The Lowdown on Mineral Makeup". WebMD. p. 3. Retrieved February 5, 2012.

- ↑ Padmavathy, Nagarajan; Vijayaraghavan, Rajagopalan (2008). "Enhanced bioactivity of ZnO nanoparticles—an antimicrobial study" (free download pdf). Science and Technology of Advanced Materials. 9 (3): 035004. Bibcode:2008STAdM...9c5004P. doi:10.1088/1468-6996/9/3/035004. PMC 5099658

.

. - ↑ Palladino, Lisa (2009-12-07). "What Is Mineral Makeup?". Luxist.com. Retrieved 2011-10-23.

- ↑ Cosper, Alex. "Purposes of Cosmetic Packaging". Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- 1 2 Cosper, Alex. "Cosmetic packaging compliant to ISO 22715". Desjardin. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ↑ Cosper, Alex. "What you should know when packaging cosmetics compliant to FDA regulations". Desjardin. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ↑ Cosper, Alex. "What you should know when packaging cosmetics compliant to EU regulations". Desjardin. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ↑ "Understanding the Cosmetics Regulation". Cosmetics Europe Association. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- ↑ International Organization for Standardization. "ISO 22715:2006 Cosmetics – Packaging and labelling". ISO.org. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ↑ Turner, Dawn M. "Is the Standard ISO 22715 on Cosmetic Packaging legally binding?". Desjardin. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ↑ Top 100 Cosmetic Manufacturers. scribd.com

- 1 2 "Cosmetic Industry". Retrieved 2010-08-04.

- ↑ "France continues to lead the way in cosmetics". Retrieved 2010-08-04.

- ↑ "Cosmetics – Europe (Italy) 2008 Marketing Research". Retrieved 2010-08-04.

- ↑ Etcoff, N. L.; Stock, S; Haley, L. E.; Vickery, S. A.; House, D. M. (2011). "Cosmetics as a Feature of the Extended Human Phenotype: Modulation of the Perception of Biologically Important Facial Signals". PLoS ONE. 6 (10): e25656. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...625656E. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025656. PMC 3185017

. PMID 21991328.

. PMID 21991328. - ↑ "Makeup Makes Women Appear More Competent: Study". The New York Times. 2011-10-12.

- ↑ Millikan, Larry E. (2001). "Cosmetology, cosmetics, cosmeceuticals: Definitions and regulations". Clinics in dermatology. 19 (4): 371–4. PMID 11535376.

- ↑ Anderson, Paul. "What Age is Too Young For Make Up". Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ↑ Singer, Natasha (March 26, 2011). "What would Estee Do?". New York Times. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ↑ Battista, Kathy. "Cindy Hinant's make-up, glamour and TV show". Phaidon. Retrieved 19 November 2014.

The American feminist artist's [Cindy Hinant] first solo show at Manhattan's Joe Sheftel Gallery plays with feminine ideals and expectations, as well as earlier artistic movements, says Dr Kathy Battista of Sotheby's Institute of Art, New York...A series of MakeUp Paintings appear as pale monochromatic works, but closer inspection reveals they are the result of the artist's daily action of blotting her face on the paper. The variation in tones calls attention to the use of makeup as artifice and the layered construction of the female self.

- ↑ "FDA Authority Over Cosmetics". fda.gov.

- ↑ "EUR-Lex – co0013 – EN – EUR-Lex". europa.eu.

- ↑ "Signers of the Compact for Safe Cosmetics". Campaign for Safe Cosmetics. Archived from the original on 2007-06-09. Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- ↑ Agner T (1991). "Susceptibility of atopic dermatitis patients to irritant dermatitis caused by sodium lauryl sulphate". Acta Derm. Venereol. 71 (4): 296–300. PMID 1681644.

- ↑ Nassif A, Chan SC, Storrs FJ, Hanifin JM (November 1994). "Abnormal skin irritancy in atopic dermatitis and in atopy without dermatitis". Arch Dermatol. 130 (11): 1402–7. doi:10.1001/archderm.130.11.1402. PMID 7979441.

- ↑ Marrakchi S, Maibach HI (2006). "Sodium lauryl sulfate-induced irritation in the human face: regional and age-related differences". Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 19 (3): 177–80. doi:10.1159/000093112. PMID 16679819.

- ↑ "7: Final Report on the Safety Assessment of Sodium Lauryl Sulfate and Ammonium Lauryl Sulfate". International Journal of Toxicology. 2 (7): 127. 1983. doi:10.3109/10915818309142005.

- ↑ Löffler H, Effendy I (May 1999). "Skin susceptibility of atopic individuals". Contact Derm. 40 (5): 239–42. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1999.tb06056.x. PMID 10344477.

- ↑ Nagel JE, Fuscaldo JT, Fireman P (April 1977). "Paraben allergy". JAMA. 237 (15): 1594–5. doi:10.1001/jama.237.15.1594. PMID 576658.

- ↑ Byford JR, Shaw LE, Drew MG, Pope GS, Sauer MJ, Darbre PD (January 2002). "Oestrogenic activity of parabens in MCF7 human breast cancer cells". J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 80 (1): 49–60. doi:10.1016/S0960-0760(01)00174-1. PMID 11867263.

- ↑ Frosch PJ, Pilz B, Andersen KE, et al. (November 1995). "Patch testing with fragrances: results of a multi-center study of the European Environmental and Contact Dermatitis Research Group with 48 frequently used constituents of perfumes". Contact Derm. 33 (5): 333–42. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1995.tb02048.x. PMID 8565489.

- ↑ Beck, M. H.; Wilkinson, S. M. (2010), "Contact Dermatitis: Allergic", Rook's Textbook of Dermatology, 2 (8th ed.), Wiley, p. 26.40

- 1 2 Johansen, Jeanne Duus; Frosch, Peter J.; Lepoittevin, Jean-Pierre (2010). Contact Dermatitis. Springer. ISBN 9783642038273. Retrieved March 13, 2014.

- ↑ Fisher, Alexander A. (2008). Fisher's Contact Dermatitis. PMPH-USA. ISBN 9781550093780.

- ↑ William D. James; Timothy Berger; Dirk Elston (2011). Andrew's Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9781437736199.

- ↑ Zhai, Hongbo; Maibach, Howard I. (2004). Dermatotoxicology (Sixth ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 9780203426272. Retrieved March 13, 2014.

- ↑ McLaughlin, Martyn (2007-12-20). "Pseudo science can't cover up the ugly truth". The Scotsman. Edinburgh.

- ↑ "Cosmetics". Badscience.net. Retrieved 2011-10-23.

- ↑ An overview of Animal Testing Issues Archived March 8, 2008, at the Wayback Machine., Humane Society of the United States. Retrieved February 27, 2008.

- 1 2 Osborn, Andrew & Gentleman, Amelia."Secret French move to block animal-testing ban", The Guardian, August 19, 2003. Retrieved February 27, 2008.

- ↑ "EUR-Lex – 32009R1223 – EN – EUR-Lex". europa.eu.

- ↑ "Product safety for manufacturers". bis.gov.uk.

- ↑ "Regulatory context". Retrieved 2010-08-04.

- ↑ "EU Cosmetic Regulation 1223/2009", European Parliament & Council, 30 November 2009, Retrieved 7 April 2015

- ↑ "Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act)". fda.gov.

- ↑ "The 1938 Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act". Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ↑ "Animal Testing". fda.gov.

- ↑ ISO 22716 ISO Guidelines on Good Manufacturing Practices, Retrieved 09/27/2012

Further reading

- Winter, Ruth (2005) [2005]. A Consumer's Dictionary of Cosmetic Ingredients: Complete Information About the Harmful and Desirable Ingredients in Cosmetics (Paperback). US: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 1-4000-5233-5.

- Begoun, Paula (2003) [2003]. Don't Go to the Cosmetics Counter Without Me(Paperback). US: Beginning Press. ISBN 1-877988-30-8.

- Carrasco, Francisco (2009) [2009]. Diccionario de Ingredientes Cosmeticos(Paperback) (in Spanish). Spain: www.imagenpersonal.net. ISBN 978-84-613-4979-1.