Cornish heraldry

Arms of the Duke of Cornwall: Sable, fifteen bezants. Bezants, adopted at an early period as a symbol of Cornwall, appear frequently in Cornish heraldry. | |

| Heraldic tradition | British |

|---|---|

| Governing body | College of Arms |

Cornish heraldry is the form of coats of arms and other heraldic bearings and insignia used in Cornwall, United Kingdom. While similar to English, Scottish and Welsh heraldry, Cornish heraldry has its own distinctive features. Cornish heraldry typically makes use of the tinctures, sable (black) and or (gold), and also uses certain creatures like Cornish choughs. It also uses the Cornish language extensively for mottoes and canting arms.

Officials and law

Carminow v. Scrope

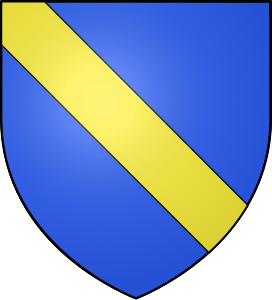

One of the earliest heraldic law cases brought in England was the 1389 case of Scrope v. Grosvenor. Scrope had found Grosvenor using the same arms as him, Azure a bend or, and set out to prove his sole right to use them. In heraldic law no two unrelated families in the same country are permitted to bear the same arms. Following a long court case it was decided that Scrope had the right to the arms and Grosvenor was forced to change his arms to Azure a garb or. It became known however that a Cornish knight by the name of Carminow was also using the disputed arms.

Carminow, seeing Scrope's use of his arms, challenged the right of Scrope to bear the arms. In this case, the constable of England declared that both claimants had established their right to the arms. Carminow had proven that his family had borne the arms "from the time of King Arthur", while the Scrope family had only used the arms "from the Norman Conquest of England". (Neither of these claims to such antiquity were in fact possible as the era of heraldry did not start until the late 12th century). The two families were, however, considered of different heraldic nations, Scrope of England, Carminow of Cornwall, and as such could both bear the same arms. As stated in the records of the case, Cornwall was in effect deemed a separate nation, "a large land formerly bearing the name of a kingdom."[1]

John Vivian and Henry Drake, in their preface to the Visitation of the County of Cornwall, commented as follows: "Cornwall may be considered pre-eminent in the antiquity of its family heraldry, since it was admitted in court during the memorable Scrope and Grosvenor controversy that the same arms, Azure a bend or, had remained in the family of Carminow from King Arthur."

Officials

There are few recorded instances of heraldic officials in the Cornish tradition, however, heralds may commonly have been employed in Cornwall primarily as minstrels and story tellers. The harpist John Hilton was appointed by King Richard II as Cornwall Herald in 1398 at about the time of the Carminow case. A Cornwall Herald attended the coronation of Henry V in 1413 and there was a Cornwall Herald at the battle of Agincourt who, with the Duke of Norfolk, was too ill to take part. During the reigns of Edward IV and Henry VII the March herald was King of Arms of the west parts of England, Wales and Cornwall.[2] Only one Cornish family is known to have had its own heraldic officer: Sir Richard Nanfan, Lord Deputy of Calais in 1503, retained a pursuivant or junior herald named Serreshal, but there may have been others.

Heraldic law

Cornish heraldry generally conformed with the rules and customs of English heraldry, and therefore with the Gallo-British tradition. However, the use of arms was far more widespread amongst the Cornish than the English and there was far less control over the use of heraldry. The antiquary Richard Carew wrote in the early 17th century, "The Cornish appear to change and diversify their arms at pleasure...The most Cornish gentlemen can better vaunt of their pedigree than their livelihood for that they derive from great antiquity, and I make question whether any shire in England of but equal quantitie can muster a like number of faire coate-armours".[3] Jewers in his Heraldic church notes from Cornwall, c. 1860-80, mentions the large number of landowners using arms never registered with the College of Arms in London. Every large farm or barton in Cornwall housed its own "Gentleman of Coat Armour".[4]

Historically primogeniture, the inheritance by the eldest son of the family estate, was not commonly practised in Cornwall. Amongst the Cornish, lands commonly were divided equally amongst all sons which resulted in smaller broken up estates, and if no sons existed lands were divided between daughters or closest relatives, male or female.[5][6] This practice may have influenced the working and development of the Cornish tradition of heraldry.[7] When primogeniture was practised, younger brothers were often married to an heiress. The heiress's arms were then adopted by the husband in place of his own family's.[3]

Duchy of Cornwall

The Duchy of Cornwall was created in 1337 from the former earldom of Cornwall. The first Duke was Edward, the Black Prince (1330-1376) who first used the badge of Three ostrich feathers. Fox-Davies states that the badge associated with the Duchy is that of the Black Bull, often termed "of Clarence".[8] Nevertheless, the Duchy is closely associated with the badge of the plume of feathers. The Black Prince erected a sculpted plume of feathers at the apex of the Duchy Palace roof at Lostwithiel when he paid his first visit there and to Restormel Castle in 1353.

The arms of the Duchy are blazoned sable, fifteen bezants. These arms were designed in the 15th century, based on the arms of Richard, Earl of Cornwall (1209-1272). The bezants in Richard's arms were intended to represent peas, known in French as pois, as a punning reference to the French region of Poitou, of which he was count.[9]

The arms are today used as a badge by Prince Charles, Duke of Cornwall and they appear below the shield in his coat of arms. The supporters used with the badge are two Cornish choughs, each holding an ostrich feather, and the motto is Houmout (meaning "high-spirited") the personal motto of the Black Prince.

Cornish symbolism

There are several charges and tinctures (colourings) used frequently in Cornish heraldry. These are derived mainly from Cornish royal and national symbolism.

Common charges

- Chough: the Cornish Chough, Cornwall's national bird, is very widely used in Cornish heraldry.

- Double-headed eagle: eagles with two heads occur prominently in several Cornish arms, in contrast to the rest of Britain where they are rare. The popularity of this form of eagle is likely due to Richard, Earl of Cornwall, who bore such an eagle in his role as King of the Romans.[10]

- Bezants: Lower describes how Cornish families took the bezant from the arms of the ancient earls of Cornwall, "this coat is pretended to from Cadock or Cradock earl of Cornwall in the fifth century". The bezant in fact derives from the arms of Richard, Earl of Cornwall, who used them to represent peas (French: pois) as a play on the name of his title Count of Poitou.

- Rose: the rose is an extremely common charge in Cornish heraldry, thought by Lower to originate in the Wars of the Roses. William Smith Ellis thought it may have been derived from an unknown Anglo-Norman family in Cornwall using it as an emblem and passing it on to their supporters. It is more likely, however, to derive from the Cornish placename element ros meaning a promontory or heathland, or res, a ford, Cornish gentry often using the name of their major estate as a surname. It is used by the family of Boscawen originally from Boscawen Rose.[10][11]

Mottoes

Many Cornish families from ancient times bore mottoes in the Cornish language, many of which were recorded in the 17th century. The practice of using Cornish language mottoes continues to this day. Examples include:

Familial examples

- Vaughan - Asgre lan dyogel ey pherchen (A good conscience is the best shield)

- Carminow - Cala rag whethlow (A straw for the talebearer)

- Glynn - Dre weres agan Dew ny (By the help of our God)

- Truscott and Gay - Gwir yn erbyn y byd (the truth against the world)

- Polwhele - Karenza wheelas Karenza (Love seeks out love)

- Tonkin - Kensol tra Tonkyn, ouna Dew mathern yn (Before all things Tonkin, fear God in the King)

- Williams - Meor vas tha dew (Gracious is thy God)

- Polkinghorne - Rag Matern a pow (For King and Country)

- Bolitho - Re deu (By God)

- Ruddle - Ruthek ha yagh (Ruddy and hearty)

- Tremenheere - Thrugscryssough ne Deu a nef (Do not disbelieve in God of Heaven)

- Tonkin - Yn ton kyn nyjyaf (In a wave I swim)

- Godolphin - Frank ha leal ettoga (Free and Loyal Forever) and Franc ha leal atho ve (Free and Loyal Am I)

- Boscawen -Bosco, Pasco, Karenza Venza (canting arms of unknown meaning, however Karensa a vynsa, covaytys ny vynsa (Love would, greed wouldn't) is a Cornish saying)

- Harris of Keneggy - Car Deu reyz pub tra (Love God above all)

- Noye of St Buryan - Teg yw hedhwch (Fair is peace)

- Gwavas - En Hav perkou Gwav (In summer remember winter)

- Sloggett of Tresloggett - Bethoh Dur (Be Bold)

- Harvey - Arva hep arveth (To arm without aggression)

- Tangye - Tangy an dorgallow

Corporate examples

- Cornish Guild of Heralds - Tyr ha Tylu (Land and Family)

- Cornwall Council - Onen hag Oll (One and All)

- Old Cornwall Society - Myghtern Arthur nyns yu marrow (King Arthur is not dead)

- Federation of Old Cornwall Societies - Kyntelleugh an brewyon es gesys na vo kellys travyth (Gather ye the fragments that are left, that nothing be lost)

- Gorseth Kernow - An gwyr erbyn an bys (The truth against the World)[12][13]

Canting arms

As with other heraldic systems canting, punning on the surname, is frequently used in Cornish heraldry. Often this uses the Cornish language suggesting it was considered a high status language. These may not reflect the true meaning or origin of the name. Examples include:

- Rose. Use is made of the rose as a charge for surnames containing ros and in mottoes can be a cant in English (rose) or Cornish (rosen, Cornish for rose).

- Cleather (Cornish - kledha, a sword) - Vert, a chevron between three swords pointed downwards Or.

- Keigwyn (Cornish - ki gwynn, a white dog) - Vert, a chevron between three greyhounds courant Argent

- Trembleth (Cornish - blyth, a wolf) - Sable, a wolf passant Argent

- Gregor (Cornish - gruk yar, partridge, lit. heather-hen) - Argent, a chevron Gules between three partridges proper.

- Molenick (Cornish - melynek, a goldfinch or greenfinch) - Argent, a chevron Sable between three goldfinches proper.

- Trenethyn (Cornish - edhen, a bird) - Argent, a Cornish Chough Sable

- Treweek (Cornish - whek, sweet) - Argent, a beehive surrounded with bees volant proper.

- Trevisa (Cornish - ys, corn) - Gules, a garb Or.

- Harvey (Cornish - havrek, arable land, harve, to harrow) - Argent, a chevron between three harrows Sable

- Whetter (Cornish - whether, blower) - Argent, a bellows between two garbs proper.

- Andean/Endean (Cornish - an den, the man) - Gules, a man statant naked proper holding in the dexter hand a cross fitchee Or, and in the sinister hand a sword Argent

- Penderill (Cornish - derow, oak trees) - Argent, on a mount an oak tree Vert, over all a fesse Purpure charged with three royal crowns Argent

- Penarth (Cornish - penn ors, bear head) - Argent, a chevron between three bears' heads erased Sable muzzled Or.

- Penwyn (Cornish - penn gwynn, white head) - Gules, three boars' heads erased in pale Argent

- Penberthy (Cornish - penn perthy, head bushes) - Argent, two choughs heads above a gorse bush proper.

- Gwyn (Cornish - gwynn, white) - Per pale Azure and Gules, three lions rampant Argent

- Pellavere/Pellover/Pellower/Pellor/Pellow (Cornish - pell owr, gold ball) - Sable, a chevron Or between three bezants.[12][13]

Supporters and crests

Supporters are figures usually placed on either side of the escutcheon which hold it up-right. In British heraldry, the use of supporters is restricted to peers, royals, Scottish barons and chiefs of clans. However a number of Cornish families, such as the Carminows and the Trevanions, do possess supporters, despite not being of noble rank as required in Scottish or English heraldry. The Carminows use: dexter, A pelican and sinister, A Cornish chough. The Trevanions: dexter, A stag, sinister A lion.[14] The Trevelyan family had Two dolphins proper as their supporters. Treffry had A man and a woman as supporters[15] The St Legers of Cornwall used A wingless griffin.[16] The office of Lord Warden of the Stannaries gave entitlement to the use of supporters. Sir Walter Raleigh, Lord Warden of the Stannaries 1584-1603, used Two wolves as his supporters from 1584 onwards.[17]

Mythology

Attributed arms

- The heraldic achievements of the Vyvyan and Trevelyan families both reflect claims that they were descended from the only survivor of the destruction of Lyonesse who escaped on the back of a white horse. The Vyvyans having a horse for their crest and on their arms a lion rising out of the waves, whilst the Trevelyan's have a white horse rising out of the waves for their arms.[18]

- Saint Piran, a 6th-century abbot who later became Cornwall's patron saint, is said to have borne sable, a cross argent. This is almost certainly untrue, as Piran lived many centuries before the birth of heraldry, but nevertheless this design is very popular today as a symbol of Cornwall, and it is used as the Cornish flag.

See also

Further reading

- Gilbert, Charles Sandoe, A Historical Survey of the County of Cornwall to which is added a Complete Heraldry of the same with Numerous Engravings, 2 vols., London, 1820. Vol.2

- Lysons, Daniel & Samuel, Magna Britannia, Vol.3, Cornwall, "Extinct Gentry Families"

References

- ↑ Cornish Heraldry and Symbolism, D. Endean Ivall, 1988. ISBN 1-850220-433 (Source: Misc. Rolls of Chanc. Nos 311 and 312.)

- ↑ Walter H. Godfrey with Sir Anthony Wagner, Survey of London Monograph 16: College of Arms, Queen Victoria Street, English Heritage, 1963 - http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=118267

- 1 2 Richard Carew, Survey of Cornwall, 1602

- ↑ Michael Trinnick, Trerice, guide book.

- ↑ Julian Cornwall, Wealth and society in early sixteenth century England, 1988

- ↑ June Z. Fullmer, Young Humphry Davy: the making of an experimental chemist, 2000

- ↑ Mr. W.C. Wade, Extinct Cornish Families, Transactions of the Plymouth Institution & Devon and Cornwall Natural History Society, 1890-1891.

- ↑ Arthur Charles Fox-Davies, A Complete Guide to Heraldry

- ↑ Planché, James (1859). The Pursuivant of Arms; or, Heraldry Founded on Facts. p. 136.

- 1 2 Lower, Mark Antony (1845). The Curiosities of Heraldry. London: JOHN RUSSELL SMITH.

- ↑ William Smith Ellis, A plea for the antiquity of heraldry: with an attempt to expound its theory and elucidate its history, 1853 - Cornish heraldry

- 1 2 W. H. Pascoe, A Cornish Armory, 1979

- 1 2 D. Endean Ivall, Cornish Heraldry and Symbolism, 1988

- ↑ D. Endean Ivall, Cornish Heraldry and Symbolism, 1988 (Sabine Baring-Gould)

- ↑ John Burke, Encyclopædia of heraldry: or General armory of England, Scotland, and Ireland, comprising a registry of all armorial bearings from the earliest to the present time, including the late grants by the College of arms, 1844

- ↑ Thomas Woodcock, John Martin Robinson, The Oxford guide to heraldry, 1988

- ↑ William Berry, Encyclopaedia heraldica or complete dictionary of heraldry, Volume 1, 1828

- ↑ Richard Polwhele, The history of Cornwall, civil, military, religious, architectural, agricultural, commercial, biographical, and miscellaneous, 1816

- Joseph Biddulph, Heraldry East (English & Cornish Armorials), 2001

- Joseph Biddulph, Heraldry West: A Crop of Armory from Western Places in England and Cornwall, 2001