Copperbelt strike of 1935

| Date | 29 May 1935 |

|---|---|

| Location | Mufulira, Nkana and Roan Antelope |

| Coordinates | 12°33′00″N 28°14′00″E / 12.55°N 28.233333°ECoordinates: 12°33′00″N 28°14′00″E / 12.55°N 28.233333°E |

| Cause | Increase of taxes |

| Casualties | |

|

6 dead 20 injured | |

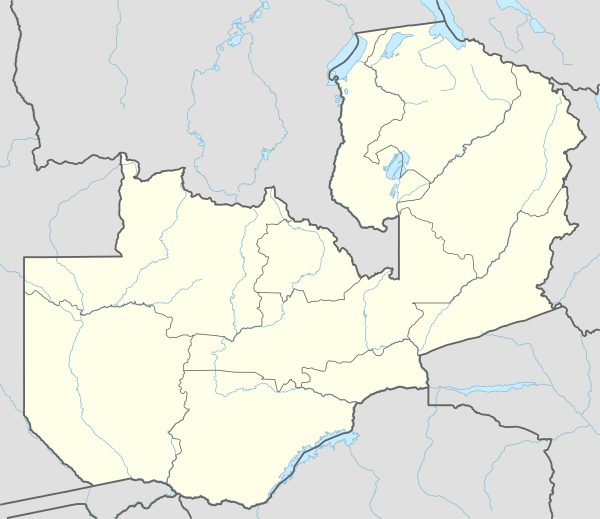

The Copperbelt strike in May 1935 was a strike by African mineworkers in the Copperbelt Province (then part of Northern Rhodesia, Zambia in modern times) on 29 May 1935 to protest against unfair taxes imposed by the British colonial administration. The strike involved three of the four major Copper mines of the province, namely those of Mufulira, Nkana and Roan Antelope. Near the latter mine the strike ended in tragedy, where six protesters were killed by the police. The strike was called off, even though they had failed in their purpose. Nevertheless, this action remains important as the first organized industrial agitation in Northern Rhodesia and is viewed by some as the first overt action against colonial rule.[1] Several men in towns of Africa realized their identity and interest leading to the creation of trade unions and African nationalist politics and it is seen as the birth of African nationalism.

Experts believe that the strike along with the other strikes in Africa during the period changed the urban and migration policies of the British government in Africa dramatically. The unrest gave the missionaries a force to take forward the Watchtower movement - the missionaries joined hands with the mining companies to impart Christian education to create a disciplined workforce. The colonial administration also created social service schemes to the rural relatives of the urban workers foreseeing future fall of Copper prices.

Background

Colonialism in Northern Rhodesia

Copperbelt Province was a province in Northern Rhodesia (modern Zambia) which was rich in copper mineral deposits. Cecil John Rhodes, a British capitalist and empire-builder was the guiding figure in British expansion north of the Limpopo River into south-central Africa.[2] In 1895, Rhodes asked his American scout Frederick Russell Burnham to look for minerals and ways to improve river navigation in the region, and it was during this trek that Burnham discovered major copper deposits along the Kafue River.[3] Rhodes effected British influence into the region by obtaining mineral rights from local chiefs under questionable treaties.[2] The Anglo-Portuguese Treaty of 1891 signed in Lisbon on 11 June 1891 between the United Kingdom and Portugal fixed the boundary between the territories administered by the British South Africa Company (BSAC) in North-Eastern Rhodesia and Portuguese Mozambique. It also fixed the boundary between the British South Africa Company administered territory of North-Western Rhodesia (now in Zambia), and Portuguese Angola, although its boundary with Angola was not marked-out on the ground until later.[2][4] The northern border of the British territory in North-Eastern Rhodesia and the British Central Africa Protectorate was agreed as a part of an Anglo-German Convention in 1890, which also fixed the very short boundary between North-Western Rhodesia and German South-West Africa, now Namibia. The boundary between the Congo Free State and British territory was fixed by a treaty in 1894, although there were some minor adjustments up to the 1930s.[5] The border between the British Central Africa Protectorate and North-Eastern Rhodesia was fixed in 1891 at the drainage divide between Lake Malawi and the Luangwa River,[6] and that between North-Western Rhodesia and Southern Rhodesia became the Zambezi River in 1898.[7] Northern Rhodesia was under the control of BSAC till 1924, after which it came under the direct control of the British Colonial Empire.[8]

Mining

The discovery of large deposits of copper sulfide during the 1900s invited large mining companies to invest in Northern Rhodesia.[9] South African interest in the region was led the Anglo American Corporation, which gained an interest in the Bwana Mkubwa company in 1924 and acquired one-third interest in Mufulira in 1928. Also in 1928, Anglo American acquired control of the Nkana mine at Kitwe and formed Rhodesian Anglo American, whose other shareholders included the United States of America, South African finance houses and the British South Africa Company (BSAC). As BSAC exchanged its own shares for Rhodesian Anglo American ones, Rhodesian Anglo American now became a major shareholder in BSAC. Both Roan Antelope and Nkana started commercial production in 1931.[10][11] By 1930, Chester Beatty's Rhodesian Selection Trust and Ernest Oppenheimer's Anglo-American Corporation became the major mining companies controlling most of the mining in the region.[9]

1935 strike

Development of the strike

The emergence of mining increased the migration of locals in search of employment from whole of Africa to the province. The mining industries improved the livelihood of the people along the rail-roads in the province. It also increased the inflow of Whites from South Africa who wanted to maintain their superiority over native Africans. On account of cultural differences, the native Africans were poorly treated by the Whites, discouraging the natives from getting employed in the mines and it gradually emerged as a race struggle. The high amount of inflow of people to the region increased the number of unplanned settlements. BSAC introduced hut tax in 1901 in North-Eastern Rhodesia and then between 1904 and 1913, in North-Western Rhodesia for all the migrants. The taxes were high, in some cases, half of the yearly salary and was aimed at creating a system of bond labor and for investing in other mines. Any unrest created due to increase in taxes were suppressed with the help of British South African Police.[12] The African miners were experiencing three major issues: low wages compared to European miners, not allowed to work in mines reserved for Europeans in spite of being highly skilled and insult and brutal behavior at the worksite.[13]

The Great Depression (1929-35) led to a fall in the price of copper in Europe. This was extremely damaging to the economy of the Copperbelt. During February 1931, Mkubwa mine was shutdown and in the following months, Chamishi, Nchanga and Mulfira mines were also closed down. The construction work of two mines at Roan Antelope and Nkana were nearing completion during the same period, leading to large scale unemployment. While the mines employed 31,941 people during September 1930, it reduced to 6,677 by the end of 1932. The African workers who were dismissed were supposed to go to their home in rural areas, but many of them stayed back.[8] During 1935, the Northern Rhodesian administration doubled the taxes in urban areas and reduced them in rural areas. It was implemented to counter the negative effects of Great Depression and losses incurred due to closure of one of the four mines in the region. The Provincial Commissioner implemented the tax during May predating it from 1 January 1935. He did it only after the Native Tax Amendment Ordinace was signed though he was informed about the change of tax regime earlier.[12]

The strike

The strike involved three of the four major Copper mines of the province, namely the ones at Mufulira, Nkana and Roan Antelope.[12] On the morning of 21 May 1935, the policemen at Mulfira relayed the information that the taxes were increased from 12 shillings to 15 shillings a year. The strike was spontaneous with the miners in the morning shift refused to go underground. Though it was unorganized, it was led by three Zambians from Northern Province, namely, William Sankata, Ngostino Mwamba and James Mutali at the Mufulira.[9] The other African miners refused to report to work, shouted slogans against the authorities and threw stones at them and unsupportive Africans.[13] The strike at the other two mines were not as spontaneous as in Mufulira, where the announcement of increase in taxes were received with disbelief. Police arrested some of the leaders in these two places as a precautionary measure. The news of strikes in Mufulira spread to the two mines with the inflow of miners to these two mines from Mufulira. The African workers went on a stern strike in Nkana on 27 May, but it was a failure and ended the next day on account of ineffective leadership. The strikes at Roan Antelope was violent where some tribal leaders participated. On 29 May 1935, a large crowd gather around the compound where police, officials, clerks and elders were drawn. The protesters started pelting stones and shouted slogans. Panicked by the action, police started firing leading to the death of six protesters and injury of 17 others.[12] Shocked by the shootout, the strikers called off the strike.[12] As per the historical record of UNESCO International Scientific Committee report, the organized mass was conducted on 22 May 1935 in Mulfra mines and spread to Nkana mines on 26 May and Luansha mines on 28 May. The death and injury toll was reported to be 28 along with an unaccounted number of arrests.[14]

Aftermath

Investigation

A commission led by Russel was appointed by the British colonial administration to investigate the causes of the strike immediately after it. The commission reported that industrialization and detribalization were the most important problems in Northern Rhodesia.[15] The commission enquiry also indicated the abrupt way in which the tax regime was implemented led to the strike.[12] It postulated two modes of authority: "The choice lies between the establishment of native authority, together with frequent repatriation of natives to their villages; or alternatively, the acceptance of definite detribalization and industrialization of the minining under European Urban control".[15] Following the enquiry, Governor Hubert Young, the Governor of Northern Rhodesia from 1935 to 1938,[16] setup a tribal leaders' advisory council for Africans in Copperbelt, similar to the one in Roan Antelope mine.[12] Some historians consider it as the conventional indirect rule that was usually imposed after similar incidents to avoid future uprising.[15]

Reform

Post 1935, all the mines were reopened and there was a steady growth in the region.[8] According to Gordon, the unrest gave the missionaries a force to take forward the Watchtower movement. The London Missionary Society and the Church of Scotland worked together, and specifically after the strike. They gathered after a week of the strike and addressed the crowd that the lack of education and religious instruction led to the strike.[17] The missionaries joined hands with the mining companies and postulated that Christian education would make them a disciplined workforce. It was termed the spiritual wing of industrial capitalism.[18] The Protestant mission in the region made rapid strides and established the United Mission of Copperbelt (UMCB), which led to the establishment of various Protestant bodies like the Church of Central Africa in Rhodesia (CCAR) in 1945, United Church of Central Africa in Rhodesia in 1958, which went on to become the United Church of Zambia in 1965.[17]

Most of the mining companies felt that the expected recovery would result in acute shortage of labor and posed a bigger challenge for economic recovery.[15] The Government also felt that if there were such fall in prices of Copper in the future, similar effects would be experienced. The colonial administration implemented two major schemes to maintain the urban-rural relationship of the urban workers with their rural home land. First, the health service expenditure of rural relatives of the urban workers were borne by the government and second, the rural male migration of working population was reduced.[19]

Historical significance

Historians believe that the strike along with other strikes in Africa during the period changed the urban and migration policies of the British government in Africa. Governor Hubert Young, after a long struggle, obtained funding for research about labour migration in Africa. Godfrey Wilson, a historian, was studying urban African labour from 1939 to 1940, but his work was suspended.[20] Though the strike achieved little, it is seen as the birth of African nationalism. Several men in towns of Africa realized their identity and interest leading to the creation of trade unionism and African nationalist politics. The actions taken by the British authorities led to five years of prosperity for the mining companies. The European miners held a strike for higher pay and were rewarded. During 1940, there were further strikes in the province in several mines that lasted over a week during which seventeen workers were killed and 65 were injured.[13]

References

- ↑ Adam, Christopher S.; Simpasa, Anthony M. (2010). "The Economics of Copper Price Boom in Zambia". In A., Fraser; M., Larmer. Zambia, Mining, and Neoliberalism: Boom and Bust on the Globalized Copperbelt. Springer. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-230-11559-0.

- 1 2 3 Galbraith, J S (1974). Crown and Charter: The early Years of the British South Africa Company. University of California Press. pp. 87, 202–3. ISBN 978-0-520-02693-3.

- ↑ Burnham, Frederick Russell (1899). "Northern Rhodesia". In Wills, Walter H. Bulawayo Up-to-date; Being a General Sketch of Rhodesia. Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co. pp. 177–180.

- ↑ Coelho, Teresa Pinto (2006). Lord Salisbury's 1890 Ultimatum to Portugal and Anglo-Portuguese Relations (PDF). pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Brownlie, I (1979). African Boundaries: A Legal and Diplomatic Encyclopaedia. Hurst & Co. pp. 706–13. ISBN 978-0-903983-87-7.

- ↑ Pike, J G (1969). Malawi: A Political and Economic History. pp. 86–7.

- ↑ Brownlie, I (1979). African Boundaries: A Legal and Diplomatic Encyclopaedia. p. 1306.

- 1 2 3 Ferguson, James (1999). Expectations of Modernity: Myths and Meanings of Urban Life on the Zambian Copperbelt. University of California Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-520-21702-7.

- 1 2 3 Henderson, Ian (October 1975). "Early African Leadership: The Copperbelt Disturbances of 1935 and 1940". 2 (1). Journal of Southern African Studies: 85–97. Retrieved 1 November 2016 – via JSTOR. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Roberts, A D (1982). Notes towards a Financial History of Copper Mining in Northern Rhodesia. pp. 348–9.

- ↑ Cunningham, S (1981). The Copper Industry in Zambia: Foreign Mining Companies in a Developing Country. pp. 53–5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Mukwena, Royson (2016). Zambia at Fifty Years: What Went Right, What Went Wrong and Wither To? a Treatise of the Countrys Socio-Economic and Political Developments Since Independence. Partridge Africa. pp. 128–129. ISBN 978-1-4828-6124-2.

- 1 2 3 Tordoff, William (1974). Politics in Zambia. University of California Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-520-02593-6.

- ↑ Boahen; International Scientific Committee for the Drafting of a General History of Africa (1990). Africa Under Colonial Domination, 1880–1935, Volume 7. Unesco: University of California Press. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-520-06702-8.

- 1 2 3 4 Cooper, Frederick (1996). Decolonization and African Society: The Labor Question in French and British Africa. Cambridge University Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-521-56600-1.

- ↑ "Major Sir H. Winthrop Young - An Able Colonial Administrator". Obituaries. The Times (51672). London. 22 April 1950. col F, p. 8.

- 1 2 Gordon, David M. (2012). Invisible Agents: Spirits in a Central African History. Ohio University Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-8214-4439-9.

- ↑ Kalusa, Walima T; Vaughan, Megan (2013). Death, Belief and Politics in Central African History. The Lembani Trust. p. 135. ISBN 978-9982-68-001-1.

- ↑ Posner, Daniel N. (2005). Institutions and Ethnic Politics in Africa. Cambridge University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-316-58297-8.

- ↑ Schumaker, Lyn (2001). Africanizing Anthropology: Fieldwork, Networks, and the Making of Cultural Knowledge in Central Africa. Duke University Press. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-8223-8079-5.