Coon song

Coon songs were a genre of music that presented a stereotyped image of Blacks. They were popular in the United States and around the English-speaking world from 1880[1] to 1920,[2] though the earliest such songs date from minstrel shows as far back as 1848.[3]

Rise and fall from popularity

The first explicitly coon-themed song, published in 1880, may have been "The Dandy Coon's Parade" by J.P. Skelley.[1] Other notable early coon songs included "The Coons Are on Parade", "New Coon in Town" (by J.S. Putnam, 1883), "Coon Salvation Army" (by Sam Lucas, 1884), "Coon Schottische" (by William Dressler, 1884).[1]

By the mid-1880s, coon songs were a national craze; over 600 such songs were published in the 1890s.[4][5] The most successful songs sold millions of copies.[4] To take advantage of the fad, composers "add[ed] words typical of coon songs to previously published songs and rags".[6]

After the turn of the century, coon songs began to receive criticism for their racist content.[7] In 1905, Bob Cole, an African-American composer who had gained fame largely by writing coon songs, made somewhat unprecedented remarks about the genre.[7] When asked in an interview about the name of his earlier comedy A Trip to Coontown, he replied, "That day has passed with the softly flowing tide of revelations."[7] Cole's comments may have been influential, and (following further criticism) the use of "coon" in song titles greatly decreased after 1910.[7]

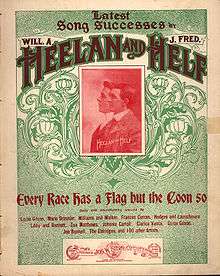

On August 13, 1920, the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League created the Red, Black and Green flag as a response to the song "Every Race Has a Flag but the Coon" by Heelan and Helf. That song along with "Coon Coon Coon" and "All Coons Look Alike To Me" were identified by H.L. Mencken as being the songs which firmly established the derogatory term "coon" in the American vocabulary.[8] Originally in the 1830s, the term had been associated with the Whig Party. The Whigs used a raccoon as its emblem, but also had a more tolerant attitude towards blacks than the other political factions. The latter opinion is likely what transformed the term "coon" from mere political slang into a racial slur.[9]

Composers

At the height of their popularity, "just about every songwriter in the country" was writing coon songs "to fill the seemingly insatiable demand".[6] Writers of coon songs included some of the most important Tin Pan Alley composers, including Gus Edwards, Fred Fisher (who wrote the 1905 "If the Man in the Moon Were a Coon", which sold three million copies),[10] and Irving Berlin.[11] Even one of John Philip Sousa's assistants, Arthur Pryor, composed coon songs.[6] (This was meant to ensure a steady supply to Sousa's band, which performed the songs and popularized several coon song melodies.[6])

Many coon songs were written by whites, but some were written by African-Americans.[5] Important black composers of coon songs include Ernest Hogan (who wrote "All Coons Look Alike to Me", the most famous coon song);[12][13] Sam Lucas (who wrote the most racist early coon songs by modern standards);[1] minstrel and songwriter Sidney L. Perrin (who wrote "Black Annie," "Dat's De Way to Spell Chicken," "Mamma's Little Pumpkin Colored Coons," Gib Me Ma 15 cents," and "My Dinah"); Bob Cole (who wrote dozens of songs, including "I Wonder What The Coon's Game Is?" and "No Coons Allowed"); and Bert Williams and George Walker.[14] Even classic ragtime composer Scott Joplin wrote at least one coon song (I Am Thinking of my Pickaninny Days), and may have composed the music for several more, using lyrics written by others.[15]

Characteristics

Coon songs almost always aimed to be funny and incorporated the syncopated rhythms of ragtime music.[4][16] Coon songs' defining characteristic, however, was their caricature of African Americans. In keeping with the older minstrel image of blacks, coon songs often featured "watermelon- and chicken-loving rural buffoon[s]".[17] However, "blacks began to appear as not only ignorant and indolent, but also devoid of honesty or personal honor, given to drunkenness and gambling, utterly without ambition, sensuous, libidinous, even lascivious."[17] Blacks were portrayed as making money through gambling, theft, and hustling, rather than working to earn a living,[17] as in the Nathan Bivins song "Gimme Ma Money":

Last night I did go to a big Crap game,

How dem coons did gamble wuz a sin and a shame...

I'm a hustling coon, ... dat's just what I am.[18]

I'm gambling for my Sadie,

Cause she's my lady,

Coon songs portrayed blacks as "hot", in this context meaning promiscuous and libidinous. They suggested that the most common living arrangement was a "honey" relationship (unmarried cohabitation), rather than marriage.[19]

Blacks were portrayed as inclined toward acts of provocative violence. Razors were often featured in the songs and came to symbolize blacks' wanton tendencies.[17] However, violence in the songs was uniformly directed at blacks instead of whites (perhaps to discharge the threatening notion of black violence amongst the coon songs' predominantly white consumers). Hence, the spectre of black-on-white violence remained but an allusion.[20] The street-patrolling "bully coon" was often used as a stock character in coon songs.[21]

The songs showed the social threats that whites believed were posed by blacks. Passing was a common theme,[22] and blacks were portrayed as seeking the status of whites, through education and money.[23] However, blacks rarely, except during dream sequences, actually succeeded at appearing white; they only aspired to do so.[24]

Use in theater

Coon songs were popular in Vaudeville theater, where they were delivered by "coon shouters", who were typically White females.[6] Notable coon shouters included Artie Hall,[25] Sophie Tucker, May Irwin, Mae West, Fay Templeton, Marie Dressler, Emma Carus, Nora Bayes, Clarice Vance, Trixie Friganza, Eva Tanguay and Julia Gerity.[6]

As with minstrel shows earlier, a whole genre of skits and shows grew up around coon songs, and often coon songs were featured in legitimate theater productions.[6]

Effects on African-American music

Coon songs, ironically, contributed to the development and acceptance of authentic African-American music.[26] Elements from coon songs were incorporated into turn-of-the-century African American folk songs, as was revealed by Howard W. Odum's 1906-1908 ethnomusicology fieldwork.[27] Similarly, coon songs lyrics influenced the vocabulary of the blues, culminating with Bessie Smith's singing in the 1920s.[26]

Black songwriters and performers who participated in the creation of coon songs profited commercially, enabling them to go on to develop a new type of African American musical theater based at least in part on African-American traditions.[26] Coon songs also contributed to the mainstream acceptance of ragtime music, paving the way for the acceptance of other African-American music.[26] Ernest Hogan, when discussing his "All Coons Look Alike to Me" shortly before his death, commented:

| “ | (That) song caused a lot of trouble in and out of show business, but it was also good for show business because at the time money was short in all walks of life. With the publication of that song, a new musical rhythm was given to the people. Its popularity grew and it sold like wildfire... That one song opened the way for a lot of colored and white songwriters. Finding the rhythm so great, they stuck to it ... and now you get hit songs without the word 'coon.' ... [Ragtime music] would have been lost to the world if I had not put it on paper.[16] | ” |

Coon songs in Britain

Coon songs became tremendously popular in Britain after the 1880s. The role of racial stereotyping in Britain was different from what it was in America, in that the theatre audiences listening to the song often did not see Black people on a day-to-day basis in their lives.

In Britain, the most important stars to popularize coon songs were Eugene Stratton, G. H. Elliott and G. H. Chirgwin. "Coon imitators" singing these songs were a staple part of British music-hall until at least 1920. Initially reserved to male artists; however, a small number of women and children increasingly began to sing coon songs at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Explaining coon songs' popularity

It is possible that the popularity of coon songs may be explained in part by their historical timing: coon songs arose precisely as the popular music business exploded in Tin Pan Alley.[4]

However, James Dormon, a former professor of history and American studies at the University of Southwestern Louisiana, has also suggested that coon songs can be seen as "a necessary sociopsychological mechanism for justifying segregation and subordination."[28] The songs portrayed Blacks as posing a threat to the American social order, and implied that they had to be controlled.[28]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Dormon, 452.

- ↑ Reublin, Parlor Songs, April 2001.

- ↑ Hubbard-Brown, Janet; Scott Joplin: Composer; Chelsea House; New York: 2006. p.22. ISBN 0-791-092-119

- 1 2 3 4 Dormon, 453.

- 1 2 Lemons, 106.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Reublin & Maine.

- 1 2 3 4 Abbott, 35.

- ↑ Mencken, 139.

- ↑ Sotiroupoulos, 91.

- ↑ Lemons, 108.

- ↑ Hamm, 145–146.

- ↑ Dormon, 459.

- ↑ Lemons, 105.

- ↑ Lemons, 107.

- ↑ Blesh, Rudi and Harris, Janet; They All Played Ragtime; Alfred P. Knopf; New York: 1950.; p.37.

- 1 2 Peress, 39.

- 1 2 3 4 Dormon, 455.

- ↑ Dormon, 456.

- ↑ Dormon, 458.

- ↑ Dormon, 460.

- ↑ Dormon, 460–461.

- ↑ Dormon, 461.

- ↑ Dormon, 462.

- ↑ Dormon, 463.

- ↑ Abbott, 17.

- 1 2 3 4 Dormon, 467.

- ↑ Abbott, 25–26.

- 1 2 Dormon, 466.

Works cited

- Abbott, Lynn, & Doug Seroff. Ragged But Right: Black Traveling Shows, Coon Songs, and the Dark Pathway to Blues and Jazz. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi (2007). ISBN 1-57806-901-7.

- Blesh, Rudi and Harris, Janet; They All Played Ragtime; Alfred P. Knopf; New York: 1950.

- Dormon, James M. Shaping the Popular Image of Post-Reconstruction American Blacks: The 'Coon Song' Phenomenon of the Gilded Age. American Quarterly 40: 450-471 (1988).

- Hamm, Charles. Genre, Performance and Ideology in the Early Songs of Irving Berlin. Popular Music 13: 143-150 (1994).

- Hubbard-Brown, Janet; Scott Joplin: Composer; Chelsea House; New York: 2006. ISBN 0-791-092-119

- Mencken, H.L. "Designations for Colored Folk" in Knickerbocker, William Skinkle,Twentieth Century English, Ayer Publishing (1970).

- Lemons, J. Stanley. "Black Stereotypes as Reflected in Popular Culture, 1880-1920." American Quarterly 29: 102-116 (1977).

- Peress, Maurice. Dvorak to Duke Ellington: A Conductor Explores America's Music and Its African American Roots Oxford University Press (2003).

- Reublin, Richard, ed. (April 2001). "Songs of the Moon". Parlor Songs. Retrieved 2014-12-24.

- Reublin, Richard A. and Robert L. Maine. "Question of the Month: What Were Coon Songs?" Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia website, Ferris State University (May 2005).

- Sotiroupoulos, Karen. Staging Race: Black Performers in Turn of the century America, Harvard University Press (2006).

External links

- Detroit Public Library Hackley Sheet Music Collection (Featuring Songs of this Genre)