Conservative Party of Canada

Conservative Party of Canada Parti conservateur du Canada | |

|---|---|

| |

| President | Scott Lamb |

| Leader of the Opposition | Rona Ambrose (interim) |

| Deputy Leader | Denis Lebel |

| Senate Opposition Leader | Claude Carignan |

| House Opposition Leader | Candice Bergen |

| Founded | 7 December 2003 |

| Merger of |

Canadian Alliance, Progressive Conservative Party of Canada |

| Headquarters |

1720 - 130 Albert Street Ottawa, Ontario K1P 5G4 |

| Ideology |

Majority: Conservatism[1] Economic liberalism[2] Fiscal conservatism[3] Federalism[4] Factions: Social conservatism[5] Red Toryism[6] Right-libertarianism[7] Right-wing populism[8] |

| Political position | Centre-right to Right-wing[9][10] |

| Continental affiliation | Asia Pacific Democrat Union |

| International affiliation |

International Democrat Union[11] Alliance of Conservatives and Reformists in Europe (regional partner)[12] |

| Colours | Blue |

| Seats in the House of Commons |

97 / 338 |

| Seats in the Senate |

41 / 105 |

| Website | |

|

English language: www French language: www | |

The Conservative Party of Canada (French: Parti conservateur du Canada), colloquially known as the Tories, is a political party in Canada. It is positioned on the right of the Canadian political spectrum.[13] The party's leader from 2004 to 2015 was Stephen Harper, who served as Prime Minister from 2006 to 2015.

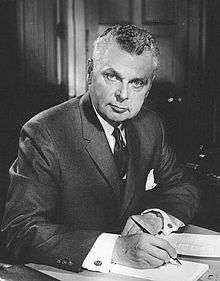

The Conservative Party is the successor to multiple right-wing parties which have existed in Canada for over a century.[14] Until 1942, one of the party's predecessors was known as the Conservative Party of Canada, and participated in numerous governments.[15] Before 1942, the predecessors to the Conservatives had multiple names, but by 1942, the main right-wing Canadian force became known as the Progressive Conservatives.[16] In 1957, John Diefenbaker became the first Prime Minister from the Progressive Conservative Party, and remained in office until 1963.[17]

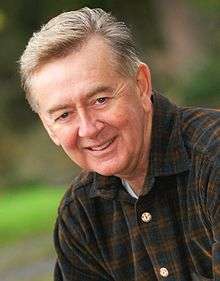

Another Progressive Conservative government was elected after the results of the 1979 federal election, with Joe Clark becoming Prime Minister. Clark served from 1979 to 1980, when he was defeated by the Liberal Party after the 1980 federal election.[18] In 1984, the Progressive Conservatives won with Brian Mulroney becoming Prime Minister.[19] Mulroney was Prime Minister from 1984 to 1993, and his government was marked by free trade agreements and economic liberalization.[20] The party suffered a near complete loss after the 1993 federal election, thanks to a splintering of the right-wing; the Conservatives' other predecessor, the Reform Party, led by Preston Manning placed in third, leaving the Progressive Conservatives in fifth. A similar result occurred in 1997, and in 2000, when the Reform Party became the Canadian Alliance.[21]

In 2003, the Canadian Alliance and Progressive Conservatives merged, forming the Conservative Party of Canada.[14] The unified Conservative Party generally favours lower taxes, small government, more decentralization of federal government powers to the provinces modeled after the Meech Lake Accord and a tougher stand on "law and order" issues. The party won two minority governments after the 2006 federal election, and a majority government in the 2011 federal election before being defeated in the 2015 federal election by a majority Liberal government.[22]

The party is currently being led by interim leader Rona Ambrose as it is undergoing a leadership election, which will take place in 2017.

Party leadership figures

Party leaders

| Leader | Term start | Term end | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| John Lynch-Staunton | 8 December 2003 | 20 March 2004 | Interim leader |

| Stephen Harper | 20 March 2004 | 19 October 2015 | Prime Minister (2006–2015) |

.jpg) | Rona Ambrose | 5 November 2015 | Incumbent | Interim leader |

John Lynch-Staunton served as interim leader of the newly created Conservative Party of Canada from 8 December 2003 until 20 March 2004, when the party elected Stephen Harper as its first leader.

On 19 January 2016, the party announced that a permanent leader will be chosen on 27 May 2017.[23]

National Council

The National Council is the party's national governing body that is elected by the Conservative Party membership at its bi-annual meetings. A National Councillor is elected for a two-year term and cannot serve for more than three consecutive terms.[24]

Composition of the National Council is based on the following criteria:

- four members from a province with more than 100 seats in the House of Commons

- three members from a province with 52–100 seats

- two from any province with 26–50 seats

- one member from each province with 4–25 seats

- one member from each territory

- the Party leader

- The Chair of the Conservative Fund Canada (in a non-voting role)

- the Executive Director (also in a non-voting role).[25]

At present, the National Council has four members from Ontario; two each from Alberta, British Columbia, and Quebec; one each from the remaining provinces and territories for a total of 19 members,[24] plus the party leader and the two non-voting members for a total 22 members.

President

The party president is elected by National Council following their election. Since 2016, the President of the Conservative Party has been Scott Lamb, a councillor representing British Columbia. The party President is the conduit between the Party Leader and the National Council.

Party presidents

- Don Plett (2003–2009) interim until 2005

- John Walsh (2009–2016)

- Scott Lamb (2016–present)

Executive Director

The Executive Director answers to the party President, and is responsible for the day-to-day management and operations of the party.

From February 2009 to October 2013, the Executive Director was Dan Hilton.

From October to December 2013, the Acting Executive Director was Dave Forestell.

Dimitri Soudas was named the new Executive Director in December 2013.[26] On 30 March 2014, Soudas was told to resign or be fired from the position after allegedly interfering with the nomination contest taking place in his fiancee's riding.[27]

On 30 March 2014, Simon Thompson was named as interim Executive Director. Thompson was previously the party's Chief Information Officer.[27]

In July 2014, Dustin Van Vugt was brought in as the Deputy Executive Director – a position created specifically for him.[28] Some media agencies, such as the CBC, suggested that this was a way for Thompson to begin handing over the work for the top job to Van Vugt, until his promotion to Executive Director could be formally ratified by the party's National Council. In October 2014, Van Vugt's position was unanimously ratified by the party's National Council, and Thompson became the Chief Operations Officer.[29]

Director of Political Operations

The Director of Political Operations reports to the Executive Director, and is one of the most important positions within the party. The person filling this role often has direct access to the party leader, due to their responsibilities for organizing the party's work on the ground and in preparing for the next election. With Stephen Harper as Prime Minister and Conservative Party leader, the Director of Political Operations has frequently moved from party positions to the Prime Minister's and other Minister's Offices, and then back to the party's headquarters, depending on the identified needs.

Doug Finley was the Director of Political Operations until 2009, when Finley was appointed to the Senate and Jenni Byrne, then Finley's Deputy, became the Director.

In August 2013, Byrne left the job to become the co-Deputy Chief of Staff in the Prime Minister's Office. Fred DeLorey, then the party's Director of Communications, became the Director.

Principles and policies

Constitution

The Conservative Party is governed by a constitution.[30] The constitution may be amended through the same procedure as outlined for "Policy Development" below.

Founding principles

The "founding principles" of the Conservative Party appear in both the constitution and the policy declaration. They are the reasons that the Conservative Party was formed, and thus the only part of the constitution and policy declaration not up for possible amendment at a national convention.

Policy development

The policy declaration of the Conservative Party is a statement of which policies the Conservative Party membership would like its Leader to implement if and when they form government.[31]

Policies are directly decided by members attending a bi-annual national convention. The rules governing the passage of those policies are formally ratified by the National Council, and clarify rules such as speaking slots and voting requirements.[32]

Policy proposals start with local riding associations, who form policy committees to discuss ideas. The riding association then puts their policies forward for discussion at a regional meeting, where they are discussed amongst a larger group of regionally based members. They are then submitted for discussion at a provincial meeting, where they are further discussed. The provincial meetings are the last level of discussions before they are placed on the agenda for the national convention’s agenda.

At the national convention, "breakout" discussion tables are formed. For example, a table may discuss several policies related to "foreign affairs" or "health care" policies. The individuals attending those breakout tables then return to their riding association delegates and encourage them to vote for the motion(s) discussed at the breakout table. During voting, individuals show their support or opposition to a proposal. If a majority agrees with the proposal, it is added to the policy declaration.

Policy declaration

The Conservative Party's policy declaration is divided into 23 pronouncements on policy:[31]

- Role of Government

- Government Accountability

- Democratic Reform

- Open Federalism

- Fiscal

- Economic Development

- Trade

- Transportation

- Environment

- Health

- Social Policy

- Aboriginal Affairs

- Criminal Justice

- Communications

- Celebrating Canada’s Diversity

- Canadian Heritage and Culture

- Rural Canada

- Agriculture

- Fisheries

- Immigration and Refugees

- Foreign Affairs

- National Defence and Security

- Strong Democracy – Ongoing Policy Development

History

Predecessors

.jpg)

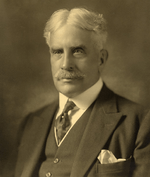

The Conservative Party is political heir to a series of right-of-centre parties that have existed in Canada, beginning with the Liberal-Conservative Party founded in 1854 by Sir John A. Macdonald and Sir George-Étienne Cartier. The party later became known simply as the Conservative Party after 1873. Like its historical predecessors and conservative parties in some other Commonwealth nations (such as the Conservative Party of the United Kingdom), members of the present-day Conservative Party of Canada are sometimes referred to as "Tories". The modern Conservative Party of Canada is also legal heir to the heritage of the historical conservative parties by virtue of assuming the assets and liabilities of the former Progressive Conservative Party upon the merger of 2003.

The first incarnations of the Conservative Party in Canada were quite different from the Conservative Party of today, especially on economic issues. The early Conservatives were known to espouse economic protectionism and British imperialism, by emphasizing Canada's ties to the United Kingdom while vigorously opposing free trade with the United States; free trade being a policy which, at the time, had strong support from the ranks of the Liberal Party of Canada.[33] The Conservatives also sparred with the Liberal Party because of its connections with French Canadian nationalists including Henri Bourassa who wanted Canada to distance itself from Britain, and demanded that Canada recognize that it had two nations, English Canada and French Canada, connected together through a common history. The Conservatives would go on with a popular slogan "one nation, one flag, one leader".

Progressive Conservative Party of Canada

The Conservative Party's popular support waned (particularly in western Canada) during difficult economic times from the 1920s to 1940s, as it was seen by many in the west as an eastern establishment party which ignored the needs of the citizens of Western Canada. Westerners of multiple political convictions including small-"c" conservatives saw the party as being uninterested in the economically unstable Prairie regions of the west at the time and instead holding close ties with the business elite of Ontario and Quebec. As a result of western alienation both the dominant Conservative and Liberal parties were challenged in the west by the rise of a number of protest parties including the Progressive Party of Canada, the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), the Reconstruction Party of Canada and the Social Credit Party of Canada. In 1921, the Conservatives were reduced to third place in number of seats in the House of Common behind the Progressives, though soon after, the Progressive Party folded. The former leader of the Progressive Party of Manitoba, John Bracken became leader of the Conservative Party in 1942 subject to several conditions, one of which was that the party be renamed the Progressive Conservative Party.

Meanwhile, many former supporters of the Progressive Conservative Party shifted their support to either the federal CCF or to the federal Liberals. The advancement of the provincially popular western-based conservative Social Credit Party in federal politics was stalled, in part by the strategic selection of leaders from the west by the Progressive Conservative Party. PC leaders such as John Diefenbaker and Joe Clark were seen by many westerners as viable challengers to the Liberals who traditionally had relied on the electorate in Quebec and Ontario for their power base. While none of the various protest parties ever succeeded in gaining significant power federally, they were damaging to the Progressive Conservative Party throughout its history, and allowed the federal Liberals to win election after election with strong urban support bases in Ontario and Quebec. This historical tendency earned the Liberals the unofficial title often given by some political pundits of being Canada's "natural governing party". Prior to 1984, Canada was seen as having a dominant-party system led by the Liberal Party while Progressive Conservative governments therefore were considered by many of these pundits as caretaker governments, doomed to fall once the collective mood of the electorate shifted and the federal Liberal Party eventually came back to power.

In 1984, the Progressive Conservative Party's electoral fortunes made a massive upturn under its new leader, Brian Mulroney, an anglophone Quebecer and former president of the Iron Ore Company of Canada, who mustered a large coalition of westerners, aggravated over the National Energy Program of the Liberal government, suburban and small-town Ontarians, and soft Quebec nationalists, who were angered over Quebec not having distinct status in the Constitution of Canada signed in 1982.[34][35] This led to a huge landslide victory for the Progressive Conservative Party. Progressive Conservatives abandoned protectionism which the party had held strongly to in the past and which had aggravated westerners and businesses and fully espoused free trade with the United States and integrating Canada into a globalized economy. This was accomplished with the signing of the Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement (FTA) of 1989 and much of the key implementation process of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which added Mexico to the Canada-U.S. free trade zone.[33]

Reform Party of Canada

In the late 1980s and 1990s, federal conservative politics became split by the creation of a new western-based protest party, the populist and social conservative Reform Party of Canada created by Preston Manning, son of Alberta Social Credit Premier Ernest Manning. It advocated deep decentralization of government power, abolition of official bilingualism and multiculturalism, democratization of the Canadian Senate, and suggested a potential return to capital punishment, and advocated significant privatization of public services. Westerners reportedly felt betrayed by the federal Progressive Conservative Party (PC), seeing it as catering to Quebec and urban Ontario interests over theirs. In 1989, Reform made headlines in the political scene when its first MP, Deborah Grey, was elected in a by-election in Alberta, which was a shock to the PCs which had almost complete electoral dominance over the province for years. Another defining event for western conservatives was when Mulroney accepted the results of an unofficial Senate "election" held in Alberta, which resulted in the appointment of a Reformer, Stanley Waters, to the Senate.

By the 1990s, Mulroney had failed to bring about Senate reform as he had promised (appointing a number of Senators in 1990). As well, social conservatives were dissatisfied with Mulroney's social progressivism. Canadians in general were furious with high unemployment, high debt and deficit, unpopular implementation of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) in 1991, and the failed constitutional reforms of the Meech Lake and Charlottetown accords. In 1993, support for the Progressive Conservative Party collapsed, and the party's representation in the House of Commons dropped from an absolute majority of seats to only two seats. The 1993 results were the worst electoral disaster in Canadian history, and the Progressive Conservatives never fully recovered.

In 1993, federal politics became divided regionally. The Liberal Party took Ontario, the Maritimes and the territories, the separatist Bloc Québécois took Quebec, while the Reform Party took Western Canada and became the dominant conservative party in Canada. The problem of the split on the right was accentuated by Canada's single member plurality electoral system, which resulted in numerous seats being won by the Liberal Party, even when the total number of votes cast for PC and Reform Party candidates was substantially in excess of the total number of votes cast for the Liberal candidate. However, this was and remains a constant issue on the political left as well for the Liberals and NDP.

Merger

Merger agreement

In 2003, the Canadian Alliance (formerly the Reform Party) and Progressive Conservative parties agreed to merge into the present-day Conservative Party, with the Alliance faction conceding its populist ideals and some social conservative elements.

On 15 October 2003, after closed-door meetings were held by the Canadian Alliance and Progressive Conservative Party, Stephen Harper (then the leader of the Canadian Alliance) and Peter MacKay (then the leader of the Progressive Conservatives) announced the "'Conservative Party Agreement-in-Principle", thereby merging their parties to create the new Conservative Party of Canada. After several months of talks between two teams of "emissaries", consisting of Don Mazankowski, Bill Davis and Loyola Hearn on behalf of the PCs and Ray Speaker Senator Gerry St. Germain and Scott Reid on behalf of the Alliance, the deal came to be.

On 5 December 2003 the Agreement-in-Principle was ratified by the membership of the Alliance by a margin of 96% to 4% in a national referendum conducted by postal ballot. On 6 December, the PC Party held a series of regional conventions, at which delegates ratified the Agreement-in-Principle by a margin of 90% to 10%. On 7 December, the new party was officially registered with Elections Canada. On 20 March 2004 Harper was elected leader.

Opposition to the merger/defections

The merger process was opposed by some elements in both parties. In the PCs in particular, the merger process resulted in organized opposition, and in a substantial number of prominent members refusing to join the new party. The opponents of the merger were not internally united as a single internal opposition movement, and they did not announce their opposition at the same moment. David Orchard argued that his written agreement with Peter MacKay, which had been signed a few months earlier at the 2003 Progressive Conservative Leadership convention, excluded any such merger. Orchard announced his opposition to the merger before negotiations with the Canadian Alliance had been completed. The basis of Orchard's crucial support for MacKay's leadership bid was MacKay's promise in writing to Orchard not merge the Alliance and PC parties. MacKay was roundly criticized for openly lying about an existential question for the PC party. Over the course of the following year, Orchard led an unsuccessful legal challenge to the merger of the two parties. MacKay's promise to not merge the Alliance and PC's was not enforceable in court, though it would have if one dollar exchanged hands as payment for consideration.

In October and November, during the course of the PC party's process of ratifying the merger, four sitting Progressive Conservative MPs — André Bachand, John Herron, former Tory leadership candidate Scott Brison, and former Prime Minister Joe Clark — announced their intention not to join the new Conservative Party caucus, as did retiring PC Party president Bruck Easton. Clark and Brison argued that the party's merger with the Canadian Alliance drove it too far to the right, and away from its historical position in Canadian politics.

On 14 January 2004 former Alliance leadership candidate Keith Martin, left the party, and sat temporarily as an independent. He was reelected, running as a Liberal, in the 2004 election, and again in 2006 and 2008.

In the early months following the merger, MP Rick Borotsik, who had been elected as Manitoba's only PC, became openly critical of the new party's leadership. Borotsik chose not to run in the 2004 general election. Brison, at first, voted for and supported the ratification of the Alliance-PC merger, then crossed the floor to the Liberals.[36] Soon afterward, he was made a parliamentary secretary in Paul Martin's Liberal government. Herron also ran as a Liberal candidate in the election, but did not join the Liberal caucus prior to the election. He lost his seat to the new Conservative Party's candidate Rob Moore. Bachand and Clark sat as independent Progressive Conservatives until an election was called in the spring of 2004, and then retired from Parliament.

Three senators, William Doody, Norman Atkins, and Lowell Murray, declined to join the new party and continued to sit in the upper house as a rump caucus of Progressive Conservatives. In February 2005, Liberals appointed two anti-merger Progressive Conservatives, Nancy Ruth and Elaine McCoy, to the Senate. In March 2006, Ruth joined the new Conservative Party.

Finally, following the 2004 federal election, Conservative Senator Jean-Claude Rivest left the party to sit as an independent (choosing not to join Senators Doody, Atkins and Murray in their rump Progressive Conservative caucus). Senator Rivest cited, as his reason for this action, his concern that the new party was too right-wing and that it was insensitive to the needs and interests of Quebec.

Leadership election, 2004

In the immediate aftermath of the merger announcement, some Conservative activists hoped to recruit former Ontario Premier Mike Harris for the leadership. Harris declined the invitation, as did New Brunswick Premier Bernard Lord and Alberta Premier Ralph Klein. Outgoing Progressive Conservative leader Peter MacKay also announced he would not seek the leadership, as did former Democratic Representative Caucus leader Chuck Strahl. Jim Prentice, who had been a candidate in the 2003 PC leadership contest, entered the Conservative leadership race in mid-December but dropped out in mid-January because of an inability to raise funds so soon after his earlier leadership bid.

In the end, there were three candidates in the party’s first leadership election: former Canadian Alliance leader Stephen Harper, former Magna International CEO Belinda Stronach, and former Ontario provincial PC Cabinet minister Tony Clement. Voting took place on 20 March 2004. A total of 97,397 ballots were cast.[37] Harper won on the first ballot with a commanding 68.9% of the vote (67,143 votes). Stronach received 22.9% (22,286 votes), and Clement received 8.2% (7,968 votes).[38]

The vote was conducted using a weighted voting system in which all of Canada’s 308 ridings were given 100 points, regardless of the number of votes cast by party members in that riding (for a total of 30,800 points, with 15,401 points required to win). Each candidate would be awarded a number of points equivalent to the percentage of the votes they had won in that riding. For example, a candidate winning 50 votes in a riding in which the total number of votes cast was 100 would receive 50 points. A candidate would also receive 50 points for winning 500 votes in a riding where 1,000 votes were cast. In practice, there were wide differences in the number of votes cast in each riding across the country. More than 1,000 voters participated in each of the fifteen ridings with the highest voter turnout. By contrast, only eight votes were cast in each of the two ridings with the lowest levels of participation.)[39] As a result, individual votes in the ridings where the greatest numbers of votes were cast were worth less than one percent as much as votes from the ridings where the fewest votes were cast.[39]

The equal-weighting system gave Stronach a substantial advantage, because of the fact that her support was strongest in the parts of the country where the party had the fewest members, while Harper tended to win a higher percentage of the vote in ridings with larger membership numbers. Thus, the official count, which was based on points rather than on votes, gave her a much better result. Of 30,800 available points, Harper won 17,296, or 56.2%. Stronach won 10,613 points, or 34.5%. Clement won 2,887 points, or 9.4%.

The actual vote totals remained confidential when the leadership election results were announced; only the point totals were made public at the time, giving the impression of a race that was much closer than was actually the case. Three years later, Harper’s former campaign manager, Tom Flanagan, published the actual vote totals, noting that, among other distortions caused by the equal-weighting system, "a vote cast in Quebec was worth 19.6 times as much as a vote cast in Alberta".[40]

2004 general election

Two months after Harper's election as national Tory leader, Liberal Party of Canada leader and Prime Minister Paul Martin called a general election for 28 June 2004.

For the first time since the 1993 federal election, a Liberal government would have to deal with an opposition party that was generally seen as being able to form government. The Liberals attempted to counter this with an early election call, as this would give the Conservatives less time to consolidate their merger. During the first half of the campaign, polls showed a rise in support for the new party, leading some pollsters to predict the election of a minority Conservative government. An unpopular provincial budget by Ontario Liberal Premier Dalton McGuinty hurt the federal Liberals in Ontario. The Liberals managed to narrow the gap and eventually regain momentum by targeting the Conservatives' credibility and motives, hurting their efforts to present a reasonable, responsible and moderate alternative to the governing Liberals.

Several controversial comments were made by Conservative MPs during the campaign. Early on in the campaign, Ontario MP Scott Reid indicated his feelings as Tory language critic that the policy of official bilingualism was unrealistic and needed to be reformed. Alberta MP Rob Merrifield suggested as Tory health critic that women ought to have mandatory family counseling before they choose to have an abortion. BC MP Randy White indicated his willingness near the end of the campaign to use the notwithstanding clause of the Canadian Constitution to override the Charter of Rights on the issue of same-sex marriage, and Cheryl Gallant, another Ontario MP, compared abortion to terrorism. The party was also criticized for issuing (quickly retracted) press releases accusing both Paul Martin and Jack Layton of supporting child pornography.

Harper's new Conservatives emerged from the election with a larger parliamentary caucus of 99 MPs while the Liberals were reduced to a minority government of 135 MPs, twenty short of a majority.

Founding convention: Montreal, March 2005

In 2005, some political analysts such as former Progressive Conservative pollster Allan Gregg and Toronto Star columnist Chantal Hébert suggested that the then-subsequent election could result in a Conservative government if the public were to perceive the Tories as emerging from the party's founding convention (then scheduled for March 2005 in Montreal) with clearly defined, moderate policies with which to challenge the Liberals. The convention provided the public with an opportunity to see the Conservative Party in a new light, appearing to have reduced the focus on its controversial social conservative agenda. It retained its populist appeal by espousing tax cuts, smaller government, and more decentralization by giving the provinces more taxing powers and decision-making authority in joint federal-provincial programs. The party's law and order package was an effort to address rising homicide rates, which had gone up 12% in 2004.[41]

2006 general election

On 17 May 2005 MP Belinda Stronach unexpectedly crossed the floor from the Conservative Party to join the Liberal Party. In late August and early September 2005, the Tories released ads through Ontario's major television broadcasters that highlighted their policies towards health care, education and child support. The ads each featured Stephen Harper discussing policy with prominent members of his Shadow Cabinet. Some analysts suggested at the time that the Tories would use similar ads in the expected 2006 federal election, instead of focusing their attacks on allegations of corruption in the Liberal government as they did earlier on.

An Ipsos-Reid Poll conducted after the fallout from the first report of the Gomery Commission on the sponsorship scandal showed the Tories practically tied for public support with the governing Liberal Party,[42] and a poll from the Strategic Counsel suggested that the Conservatives were actually in the lead. However, polling two days later showed the Liberals had regained an 8-point lead.[43] On 24 November 2005 Opposition leader Stephen Harper introduced a motion of no confidence which was passed on 28 November 2005. With the confirmed backing of the other two opposition parties, this resulted in an election on 23 January 2006 following a campaign spanning the Christmas season.

The Conservatives started off the first month of the campaign by making a series of policy-per-day announcements, which included a Goods and Services Tax reduction and a child-care allowance. This strategy was a surprise to many in the news media, as they believed the party would focus on the sponsorship scandal; instead, the Conservative strategy was to let that issue ruminate with voters. The Liberals opted to hold their major announcements after the Christmas holidays; as a result, Harper dominated media coverage for the first few weeks of the campaign and was able "to define himself, rather than to let the Liberals define him". The Conservatives' announcements played to Harper's strengths as a policy wonk,[44] as opposed to the 2004 election and summer 2005 where he tried to overcome the perception that he was cool and aloof. Though his party showed only modest movement in the polls, Harper's personal approval numbers, which had always trailed his party's significantly, began to rise relatively rapidly.

On 27 December 2005 the Royal Canadian Mounted Police announced it was investigating Liberal Finance Minister Ralph Goodale's office for potentially engaging in insider trading before making an important announcement on the taxation of income trusts. The revelation of the criminal investigation and Goodale's refusal to step aside dominated news coverage for the following week, and it gained further attention when the United States Securities and Exchange Commission announced they would also launch a probe. The income trust scandal distracted public attention from the Liberals' key policy announcements and allowed the Conservatives to refocus on their previous attacks on corruption within the Liberal party. The Tories were leading in the polls by early January 2006, and made a major breakthrough in Quebec where they displaced the Liberals as the second place party (after the Bloc Québécois).

In response to the growing Conservative lead, the Liberals launched negative ads suggesting that Harper had a "hidden agenda", similar to the attacks made in the 2004 election. The Liberal ads did not have the same effect this time as the Conservatives had much more momentum, at one stage holding a ten-point lead. Harper's personal numbers continued to rise and polls found he was considered not only more trustworthy, but also a better potential Prime Minister than Paul Martin. In addition to the Conservatives being more disciplined, media coverage of the Conservatives was also more positive than in 2004. By contrast, the Liberals found themselves increasingly criticized for running a poor campaign and making numerous gaffes.

On 23 January 2006 the Conservatives won 124 seats, compared to 103 for the Liberals. The results made the Conservatives the largest party in the 308-member House of Commons, enabling them to form a minority government. On 6 February, Harper was sworn in as the 22nd Prime Minister of Canada, along with his Cabinet.

First Harper government (2006–2008)

2008 general election

On 7 September 2008 Stephen Harper asked the Governor General of Canada to dissolve parliament. The election took place on 14 October. The Conservative Party returned to government with 143 seats, up from the 127 seats they held at dissolution, but short of the 155 necessary for a majority government. This was the third minority parliament in a row, and the second for Harper. The Conservative Party pitched the election as a choice between Harper and the Liberals' Stéphane Dion, whom they portrayed as a weak and ineffective leader. The election, however, was rocked midway through by the emerging global financial crisis and this became the central issue through to the end of the campaign. Harper has been criticised for appearing unresponsive and unsympathetic to the uncertainty Canadians were feeling during the period of financial turmoil, but he countered that the Conservatives were the best party to navigate Canada through the financial crisis, and portrayed the Liberal "Green Shift" plan as reckless and detrimental to Canada's economic well-being. The Conservative Party released its platform on 7 October.[45] The platform states that it will re-introduce a bill similar to C-61.[46]

Second Harper government (2008–2011)

Policy convention: Winnipeg, November 2008

The party’s second convention was held in Winnipeg in November 2008. This was the party's first convention since taking power in 2006, and media coverage concentrated on the fact that this time, the convention was not very policy-oriented, and showed the party to be becoming an establishment party. However, the results of voting at the convention reveal that the party’s populist side still had some life. A resolution that would have allowed the party president a director of the party’s fund was defeated because it also permitted the twelve directors of the fund to become unelected ex officio delegates.[47] Some controversial policy resolutions were debated, including one to encourage provinces to utilize "both the public and private health sectors", but most of these were defeated.

Third Harper government (2011–2015)

Leadership selection process

Following the election of a Liberal Government in the 2015 General Election, the Party announced that Stephen Harper was stepping down as leader and that an interim leader would be selected to serve until a new leader could be chosen.[48] That was completed at the caucus meeting of 5 November 2015[49] where Rona Ambrose MP for Sturgeon River—Parkland and a former cabinet minister was elected by a vote of MPs and Senators.[50]

Some members of the party’s national council were calling for a leadership convention as early as May 2016 according to Maclean's magazine.[51] However, some other Members of Parliament wanted the vote to be delayed until the spring of 2017.[52] On 19 January 2016, the party announced that a permanent leader will be chosen on 27 May 2017.[23]

Electoral results

| Election | Leader | Votes | % | Seats | +/– | Position | Government |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | Stephen Harper | 4,019,498 | 29.63 | 99 / 308 |

|

|

Opposition |

| 2006 | Stephen Harper | 5,374,071 | 36.27 | 124 / 308 |

|

|

Minority |

| 2008 | Stephen Harper | 5,209,069 | 37.65 | 143 / 308 |

|

|

Minority |

| 2011 | Stephen Harper | 5,832,401 | 39.62 | 166 / 308 |

|

|

Majority |

| 2015 | Stephen Harper | 5,578,101 | 31.9 | 99 / 338 |

|

|

Opposition |

Regional conservative parties

The Conservative Party, while having no provincial wings, largely works with the former federal Progressive Conservative Party's provincial affiliates. There have been calls to change the names of the provincial parties from "Progressive Conservative" to "Conservative". However, there are other small "c" conservative parties with which the federal Conservative Party has close ties, such as the Saskatchewan Party and the British Columbia Liberal Party (not associated with the federal Liberal Party of Canada). The federal Conservative Party has the support of many of the provincial Conservative leaders. In Ontario, successive provincial PC Party leaders John Tory, Bob Runciman and Tim Hudak have expressed open support for Stephen Harper and the Conservative Party of Canada, while former Mike Harris cabinet members Tony Clement, and John Baird were ministers in Harper's government. In Quebec, businessman Adrien D. Pouliot leads a new Conservative Party of Quebec which was formed in 2009 in the wake of the decline of the Action démocratique du Québec (ADQ) which had carried the support of many provincial conservatives.

Cross-support between federal and provincial Conservatives is more tenuous in some other provinces. In Alberta, relations became strained between the federal Conservative Party and the Progressive Conservatives. Part of the federal Tories' loss in the 2004 election was often blamed on then Premier Klein's public musings on health care late in the campaign. Klein had also called for a referendum on same-sex marriage. With the impending 2006 election, Klein predicted another Liberal minority, though this time the federal Conservatives won a minority government. Klein's successor Ed Stelmach tried to avoid causing similar controversies; however, Harper's surprise pledge to restrict bitumen exports drew a sharp rebuke from the Albertan government, who warned such restrictions would violate both the Constitution of Canada and the North American Free Trade Agreement. The rise of the Wildrose Party in Alberta has caused a further rift between the federal Conservatives and the Albertan PCs, as some Conservative backbench MPs endorse Wildrose. For the 2012 Alberta election, Prime Minister Harper remained neutral and instructed federal cabinet members to also remain neutral while allowing Conservative backbenchers to back whomever they chose if they wish. Wildrose candidates for the concurrent Senate nominee election announced they would sit in the Conservative caucus should they be appointed to the Senate.

After the 2007 budget was announced, the Progressive Conservative governments in Nova Scotia and Newfoundland & Labrador accused the federal Conservatives of breaching the terms of the Atlantic Accord.

As a result, relations worsened between the two provincial governments, leading Newfoundland & Labrador Premier Danny Williams to denounce the federal Conservatives, which gave rise to his ABC (Anything But Conservative) campaign in the 2008 election.

See also

References

- ↑ Farney, James (2013), Conservatism in Canada, University of Toronto Press, p. 209

- ↑ Joseph, Thomas (2009), 8 Days of Crisis on the Hill; Political Blip Or Stephen Harper's Revolution Derailed?, iUniverse, p. 159

- ↑ Bittner, Amanda (2013), Parties, Elections, and the Future of Canadian Politics, UBC Press, p. 134

- ↑ "How Stephen Harper's open federalism changed Canada for the better". Maclean's. December 1, 2015.

- ↑ . Ottawa Citizen http://ottawacitizen.com/opinion/columnists/kaplan-wide-ideological-differences-will-take-centre-stage-as-conservatives-hold-first-debate. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ . Ottawa Citizen http://ottawacitizen.com/opinion/columnists/kaplan-wide-ideological-differences-will-take-centre-stage-as-conservatives-hold-first-debate. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ . Ottawa Citizen http://ottawacitizen.com/opinion/columnists/kaplan-wide-ideological-differences-will-take-centre-stage-as-conservatives-hold-first-debate. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ http://www.macleans.ca/politics/how-kellie-leitch-touched-off-a-culture-war/

- ↑ "Political Parties of Canada » J.J.'s Complete Guide to Canada". thecanadaguide.com. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ↑ Andrea Olive (2015). The Canadian Environment in Political Context. University of Toronto Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-4426-0871-9.

- ↑ "IDU.org". IDU.org. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 2012-03-01.

- ↑ "ACRE - EUROPE'S FASTEST GROWING POLITICAL MOVEMENT". aecr.eu. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ↑ "Platform:Conservative Party". Ottawa Citizen.

- 1 2 "Conservative Party". Canadian Encyclopedia.

- ↑ "History of the Conservative Party". Quebec History.

- ↑ "Progressive Conservative Party of Canada". Encylopaedia Britannica.

- ↑ Newman 1963, pp. 58–59

- ↑ "PM Joe Clark". Prime Minister of Canada Website.

- ↑ "PARLINFO – Parliamentarian File – Federal Experience – MULRONEY, The Right Hon. Martin Brian, P.C., C.C., G.O.Q., B.A., LL.L.". Parliament of Canada. Retrieved 26 June 2011.

- ↑ "Joe Clark". The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- ↑ "Reform Party". CanadianHistory.

- ↑ "Canadian Past Election Results". Canadian elections.

- 1 2 The Canadian Press; no by-line.--> (19 January 2016). "ext Conservative party leader will be chosen May 27, 2017, party says". National Newswatch. National Newswatch Inc. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- 1 2 "Conservative Party of Canada". conservative.ca. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ↑ http://www.conservative.ca/media/2012/06/Sept2011-Constitution-E.pdf

- ↑ "Harper loyalist Dimitri Soudas named executive director of Conservative Party of Canada | National Post". News.nationalpost.com. Retrieved 2014-08-12.

- 1 2 "Dimitri Soudas fired as Conservative Party executive director - Politics - CBC News". Cbc.ca. Retrieved 2014-08-12.

- ↑ "Conservative Party names new deputy executive director". cbc.ca. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ↑ http://www.conservative.ca/media/2014/10/october-nc-report.pdf

- ↑ http://www.conservative.ca/media/documents/constitution-en.pdf

- 1 2 http://www.conservative.ca/media/documents/Policy-Declaration-Feb-2014.pdf

- ↑ http://www.conservative.ca/media/2013/05/Rules-for-Constitution-and-Policy-Discussions-Conservative-Party-of-Canada-2013-Convention.pdf

- 1 2 Hoberg, George. "Canada and North American S35 Integration" (PDF). Canadian Public Policy. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ↑ "Wooing nationalists is a risky courtship". The Montreal Gazette. 9 September 2008. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ↑ Gunter, Lorne (19 October 2011). "Shipbuilding contract is an iceberg waiting to be hit". The National Post. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ↑ "MacKay slams Brison for joining the Liberals". CBC.ca. 10 December 2003. Retrieved 2011-03-28.

- ↑ Tom Flanagan, Harper’s Team. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2007, pg. 131

- ↑ Tom Flanagan, Harper's Team. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2007, pg. 133

- 1 2 Tom Flanagan, Harper's Team. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2007, pg. 135

- ↑ Tom Flanagan, Harper’s Team. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2007, pg. 134

- ↑ "Statistics Canada re spike in homicides". Statcan.ca. 21 July 2005. Archived from the original on 31 August 2008. Retrieved 2011-05-05.

- ↑ "Grits Thrashed in Wake of Gomery Report". Ipsos-na.com. 4 November 2005. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ "Canada Federal Election 2010 - Public Opinion Polls - National - Election Almanac". Electionalmanac.com. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ "andrewcoyne.com". Web.archive.org. Archived from the original on 16 November 2006. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ "Canada Votes – Reality Check – The Conservative platform". Web.archive.org. Archived from the original on 7 March 2013. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ "CBC News – Technology & Science – Conservatives pledge to reintroduce copyright reform". CBC.ca. 7 October 2008. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ "Convention Watch: 2008". Blog.macleans.ca. 15 November 2008. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ↑ "Diane Finley Plans To Run For Interim Conservative Leadership". huffingtonpost.ca. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ↑ "Conservatives choose Alberta MP Rona Ambrose as interim leader". cbc.ca. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ↑ http://www.rcinet.ca/en/2015/11/05/rona-ambrose-elected-interim-conservative-leader/

- ↑ Paul Wells. "Conservative caucus unrest mounts". Macleans.ca. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ↑ The Hill Times. "Conservative MPs calling on party to hold leadership convention in spring 2017". hilltimes.com. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

Further reading

Archival holdings

- Conservative Party of Canada - Canadian Political Parties and Political Interest Groups - Web Archive created by the University of Toronto Libraries

- Conservative Party of Canada (French) - Canadian Political Parties and Political Interest Groups - Web Archive created by the University of Toronto Libraries

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Conservative Party of Canada. |