Complement graph

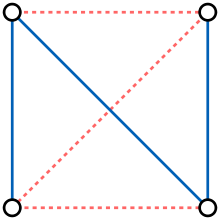

In graph theory, the complement or inverse of a graph G is a graph H on the same vertices such that two distinct vertices of H are adjacent if and only if they are not adjacent in G. That is, to generate the complement of a graph, one fills in all the missing edges required to form a complete graph, and removes all the edges that were previously there.[1] It is not, however, the set complement of the graph; only the edges are complemented.

Definition

Let G = (V, E) be a simple graph and let K consist of all 2-element subsets of V. Then H = (V, K \ E) is the complement of G.[2] For directed graphs, the complement can be defined in the same way, as a directed graph on the same vertex set, using the set of all 2-element ordered pairs of V in place of the set K in the formula above.

The complement is not defined for multigraphs. In graphs that allow self-loops (but not multiple adjacencies) the complement of G may be defined by adding a self-loop to every vertex that does not have one in G, and otherwise using the same formula as above. This operation is, however, different from the one for simple graphs, since applying it to a graph with no self-loops would result in a graph with self-loops on all vertices.

Applications and examples

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

Several graph-theoretic concepts are related to each other via complement graphs:

- The complement of an edgeless graph is a complete graph and vice versa.

- Any induced subgraph of the complement graph of a graph G is the complement of the corresponding induced subgraph in G.

- An independent set in a graph is a clique in the complement graph and vice versa. This is a special case of the previous two properties, as an independent set is an edgeless induced subgraph and a clique is a complete induced subgraph.

- The complement of every triangle-free graph is a claw-free graph,[3] although the reverse is not true.

- The vertices of the Kneser graph KG(n,k) are the k-subsets of an n-set, and the edges are between disjoint sets. The complement is the Johnson graph J(n,k), where the edges are between intersecting sets.[4]

Self-complementary graphs and graph classes

A self-complementary graph is a graph that is isomorphic to its own complement.[1] Examples include the four-vertex path graph and five-vertex cycle graph.

Several classes of graphs are self-complementary, in the sense that the complement of any graph in one of these classes is another graph in the same class.

- Perfect graphs are the graphs in which, for every induced subgraph, the chromatic number equals the size of the maximum clique. The fact that the complement of a perfect graph is also perfect is the perfect graph theorem of László Lovász.[5]

- Cographs are defined as the graphs that can be built up from single vertices by disjoint union and complementation operations. They form a self-complementary family of graphs: the complement of any cograph is another different cograph. For cographs of more than one vertex, exactly one graph in each complementary pair is connected, and one equivalent definition of cographs is that each of their connected induced subgraphs has a disconnected complement. Another, self-complementary definition is that they are the graphs with no induced subgraph in the form of a four-vertex path.[6]

- Another self-complementary class of graphs is the class of split graphs, the graphs in which the vertices can be partitioned into a clique and an independent set. The same partition gives an independent set and a clique in the complement graph.[7]

- The threshold graphs are the graphs formed by repeatedly adding either an independent vertex (one with no neighbors) or a universal vertex (adjacent to all previously-added vertices). These two operations are complementary and they generate a self-complementary class of graphs.[8]

Algorithmic aspects

In the analysis of algorithms on graphs, the distinction between a graph and its complement is an important one, because a sparse graph (one with a small number of edges compared to the number of pairs of vertices) will in general not have a sparse complement, and so an algorithm that takes time proportional to the number of edges on a given graph may take a much larger amount of time if the same algorithm is run on an explicit representation of the complement graph. Therefore, researchers have studied algorithms that perform standard graph computations on the complement of an input graph, using an implicit graph representation that does not require the explicit construction of the complement graph. In particular, it is possible to simulate either depth-first search or breadth-first search on the complement graph, in an amount of time that is linear in the size of the given graph, even when the complement graph may have a much larger size.[9] It is also possible to use these simulations to compute other properties concerning the connectivity of the complement graph.[9][10]

References

- 1 2 Bondy, John Adrian; Murty, U. S. R. (1976), Graph Theory with Applications (PDF), North-Holland, p. 6, ISBN 0-444-19451-7.

- ↑ Diestel, Reinhard (2005), Graph Theory (3rd ed.), Springer, ISBN 3-540-26182-6. Electronic edition, page 4.

- ↑ Chudnovsky, Maria; Seymour, Paul (2005), "The structure of claw-free graphs" (PDF), Surveys in combinatorics 2005, London Math. Soc. Lecture Note Ser., 327, Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, pp. 153–171, MR 2187738..

- ↑ Bailey, Robert F.; Cáceres, José; Garijo, Delia; González, Antonio; Márquez, Alberto; Meagher, Karen; Puertas, María Luz (2013), "Resolving sets for Johnson and Kneser graphs", European Journal of Combinatorics, 34 (4): 736–751, doi:10.1016/j.ejc.2012.10.008, MR 3010114.

- ↑ Lovász, László (1972a), "Normal hypergraphs and the perfect graph conjecture", Discrete Mathematics, 2 (3): 253–267, doi:10.1016/0012-365X(72)90006-4.

- ↑ Corneil, D. G.; Lerchs, H.; Stewart Burlingham, L. (1981), "Complement reducible graphs", Discrete Applied Mathematics, 3 (3): 163–174, doi:10.1016/0166-218X(81)90013-5, MR 0619603.

- ↑ Golumbic, Martin Charles (1980), Algorithmic Graph Theory and Perfect Graphs, Academic Press, Theorem 6.1, p. 150, ISBN 0-12-289260-7, MR 0562306.

- ↑ Golumbic, Martin Charles; Jamison, Robert E. (2006), "Rank-tolerance graph classes", Journal of Graph Theory, 52 (4): 317–340, doi:10.1002/jgt.20163, MR 2242832.

- 1 2 Ito, Hiro; Yokoyama, Mitsuo (1998), "Linear time algorithms for graph search and connectivity determination on complement graphs", Information Processing Letters, 66 (4): 209–213, doi:10.1016/S0020-0190(98)00071-4, MR 1629714.

- ↑ Kao, Ming-Yang; Occhiogrosso, Neill; Teng, Shang-Hua (1999), "Simple and efficient graph compression schemes for dense and complement graphs", Journal of Combinatorial Optimization, 2 (4): 351–359, doi:10.1023/A:1009720402326, MR 1669307.