Clifton Park, Baltimore

|

Clifton Park | |

|

"Clifton Mansion", original home of Capt. Henry Thompson, (1774-1837), later purchased 1838 by Johns Hopkins, (1795-1873), renovated/redesigned around 1858 by architectural team of Niernsee and Neilson, photo taken August 2011 | |

| |

| Location | Bounded by Hartford Rd., Erdman Ave., Clifton Park Terrace, the Baltimore Belt RR and Sinclair Ln., Baltimore, Maryland |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 39°19′15″N 76°34′58″W / 39.32083°N 76.58278°WCoordinates: 39°19′15″N 76°34′58″W / 39.32083°N 76.58278°W |

| Area | 266.7 acres (107.9 ha) |

| Built | 1801 |

| Architect | Niersee & Neilson; Wyatt and Nolting; Olmsted Brothers; Thomas, Frederick |

| Architectural style | Italian Villa, Gothic Revival, Late 19th & 20th C. Revival |

| NRHP Reference # | 07000941[1] |

| Added to NRHP | September 12, 2007 |

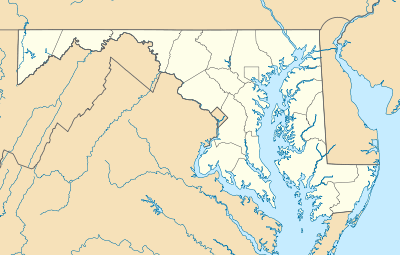

Clifton Park is a public urban park and national historic district located between the Coldstream-Homestead-Montebello and Waverly neighborhoods to the west and the Belair-Edison, Lauraville, Hamilton communities to the north in the northeast section of Baltimore, Maryland, U.S.A.. It is roughly bordered by Erdman Avenue (Md. Rt. 151) to the northeast, Sinclair Lane to the south, Harford Road (Md. Rt. 147) to the northwest and Belair Road (U.S. Route 1) to the southeast.[2] The eighteen-hole Clifton Park Golf Course, which is the site of the annual Clifton Park Golf Tournament,[3] occupies the north side of the park.

History

The land on which Clifton Park sits was once farmland. Built around 1803, the home was originally the summer residence of Capt. Henry Thompson, (1774-1837). Born in Sheffield, England, he came to Baltimore around 1794, and soon became a prominent figure in the newly-emerging City and its history. Became a well-known merchant, financier and company director, he also was a very public-spirited citizen and used his knowledge of horses in military matters. Serving as a cavalry officer in the Maryland Militia, of which a part was the "Baltimore Light Dragoons" which he joined in 1809 and elected captain. Later organized in 1813, the "First Baltimore Horse Artillery" who defended Baltimore from the British attack during the War of 1812 at the Battle of Baltimore with its Bombardment of Fort McHenry, the Battle of North Point in the southeastern reaches of surrounding, then rural Baltimore County on the Patapsco Neck peninsula, and the stand-off at Loudenschlager's Hill/Hampstead Hill (now Patterson Park) in East Baltimore, on September 12-13-14, 1814, celebrated later in the city/county/state as an official holiday as "Defenders' Day". He was assigned by Brig. Gen. John Stricker, commander of the Third Brigade (also known as the Baltimore City Brigade) of the Maryland State Militia, to carry messages between Bladensburg, Maryland (in Prince George's County) and the nearby national capital of Washington, D.C. during the first phase of the British attack and the tragic collapse at the Battle of Bladensburg, which resulted in the unfortunate Burning of Washington during the Chesapeake Bay campaign in August 1814. Later he and his mounted unit served as the personal bodyguard of Maj. Gen. Samuel Smith, overall commander of the State Militia under the then Governor of Maryland, Levin Winder, and the various militia forces from surrounding counties and states, including several Regular United States Army and Navy units and detachments defending Baltimore in September 1814. Along with the former Georgian/Federal style mansion of "Surrey" of Col. Joseph Sterrett, (1773-1821), commander of the 5th Maryland Regiment, (later famously known as the "Dandy Fifth"), further east of the Town, (now greatly changed/gutted/damaged/renovated and used as a community center in Armistead Gardens, off Erdman Avenue (Md. Rt. 151) and Federal Street), it is considered the only two structures besides the 1793 Flag House & Star-Spangled Banner Museum of Mary Pickersgill at East Pratt and Albemarle Streets, in Jonestown/Old Town and the Old St. Paul's Church Rectory on West Saratoga Street to be a residence still extant from the famous attack which inspired the writing of our National Anthem, "Star Spangled Banner".

Later in private and business life, Thompson served as President of the Baltimore and Harford Turnpike Company which began building the northeastern spoke road out of the City, now known as Harford Road (Md. Rt. 147). Later he was part of the Poppleton Commission under city surveyor and mapmaker Thomas Poppleton which laid out additional grids of streets and blocks for the city's future expansion and prepared a well-known map and diagram of the new sections and the larger city in 1818, resulting in the first major large scale annexation of the territory around the City known as "The Precincts" from surrounding rural Baltimore County, that year. He also served as member of the boards of directors of the Baltimore and Port Deposit Railroad, the third major Baltimore railroad chartered in Maryland and one of the first in America, (later merged with several other smaller connecting lines into the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad - eventually into the dominant northeast line, the Pennsylvania Railroad by 1881), the Bank of Baltimore - second financial institution in the city, the landmark domed Merchants' Exchange Building, (largest magnificent structure then in America - designed by famed architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe, 1815-1820), (at East Lombard, Water and South Gay Streets), the Baltimore Board of Trade, and the Maryland Agricultural Society. He was honored with the position of being Marshall of the Proceedings at the Cornerstone-Laying for both the Battle Monument, (on North Calvert Street, between East Fayette and Lexington Streets), on the first Defenders' Day anniversary of the engagement, September 12, 1815, and the iconic Washington Monument earlier on "Independence Day", July 4, 1815, on a prominence in "Howard's Woods" just north then of the developed city. In later years, Thompson also served as the Grand Marshall of the festivities in Baltimore surrounding the return and the touring visit to America of the French patriot and American supporter, Marquis de Lafayette, former aide to commanding General George Washington and also General in our Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War in 1824. Thompson maintained ownership of the estate until about 1835, however dying two years later in 1837.

In 1838, it was bought by local merchant, financier and philanthropist Johns Hopkins, (1795-1873), for his estate (along with his city brick/marble trim Greek Revival styled mansion on West Saratoga Street between North Charles and Cathedral-Liberty-South Sharp Streets, next to and just east of the old St. Paul's Church Rectory where he later died), and was later developed with a nearby lake and a large sculpture collection.[2]

Later, in 1858, it was converted into an Italianate villa by the locally-famous architects John Rudolph Niernsee, (1814-1885), and James Crawford Neilson, (1816-1900), with a tall landmark tower added. It was originally planned by Mr. Hopkins to locate the campus of his future bequest of The Johns Hopkins University there on that substantial property which later opened in February 1876, but was relocated by his appointed Board of Trustees and its newly-recruited first President, Daniel Coit Gilman (1831-1908, served 1875-1901), for monetary reasons resulting from low values on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad company stock which was then in financial difficulties and formed the major part of the new school's endowment bequest. Also to utilize the rich research-reference academic assets and resources of the Peabody Institute (founded1857, opened 1866), with its new east wing expansion with a visually stunning multi-level cast-iron balconies of tightly packed book stacks surmounted by a 61 - foot high heavy glass paned skylight at the George Peabody Library, opening in 1878), plus the nearby location of a possible preparatory secondary school in the Baltimore City College, the City's well-regarded all-boys premier public high school and third oldest in America, having been founded in 1839. In addition, in order to preserve as much of the funds developed by the interest on the forbidden use of the endowment's principal, to first situate itself in several downtown buildings built along North Howard and Little Ross/West Centre Streets (between West Centre and West Monument Streets in the southwest corner of the Mount Vernon-Belvedere neighborhood). There the J.H.U. remained for the first three decades of its existence. By the middle 1890s, with a divided Board and the continued lower rate of return on the Hopkins endowment which was still mostly invested in Baltimore and Ohio Railroad company stock which was still undergoing occasional financial instability and had lost considerable value, the University sold the acreage of the old "Clifton" estate to the City for use as a park for the northeast sections adding to the city's growing parks system, temporarily giving up on its dream of a larger, more spacious and distinctive campus for its burgeoning world-wide academic reputation as the "first modern university in America". It was not until about 1900, that additional efforts for a larger, more suburban campus were made once again and came to fruition through the efforts of William Wyman and others through the purchase and donation of the wooded Homewood estate (built around 1801 for his son, Charles Carroll, Jr. by Charles Carroll of Carrollton, (1737-1832), and inherited by Wyman from the son's (also known later as Charles Carroll of Homewood) estate, with its landmark Georgian/Federal-style architecture mansion, to the north along the west side of North Charles Street, adjacent to the west of the old Peabody Heights neighborhood, (later renamed Charles Village in 1967). Hopkins' first new buildings at Homewood were constructed in 1914-1915 to match the red brick and white wooden trim in the colonial/Georgian/Federal style of the old mansion, and the JHU move followed during the years afterwards.[4]

In 1916, Peabody Institute trustees gave Baltimore City "On the Trail," a 7-foot-4 bronze sculpture of a Native American man created by local artist/sculptor Edward Berge, and it was placed upon a boulder in Clifton Park. The statue is reported to have been generally overlooked by those visiting the park, though it has been subjected to periodic vandalism.[5][6]

Amenities

The old "Clifton" mansion from when it was a farmland was once used as the pro shop at the golf course and offices for the Baltimore City Department of Recreation and Parks.[2][n 1] Now, the headquarters of a local service based nonprofit, Civic Works, inc., are located within the Clifton Mansion. Civic Works is currently doing a $7 million renovation to the Clifton Mansion.[7] The Clifton Mansion address is 2701 Saint Lo Drive; Baltimore, Maryland, 21213.

On the land is the Clifton Park Valve House, an 8-sided distinctive stone structure with a cone tile roof that has become a local landmark that was used beginning in 1887 as a water transporter, with eight valves for the adjacent "Lake Clifton", part of the second water supply system for Baltimore City excavated and constructed in the late 19th century. It supplied water for the whole village and water for cropping. The water works system was begun prior to the purchase of the old Thompson/Hopkins estate from the JHU Board of Trustees as a public park for the expanding northeastern city in 1894, following the second major annexation from surrounding Baltimore County in 1888.

Nearby on the edge of Clifton Park was its public water system reservoir "Lake Clifton". Later during the 1930s, on the southern edge of the park had earlier been constructed one of the new type of lower-level high schools then becoming popular during the 1920s in America known as junior high schools, a co-educational Clifton Park Junior High School was opened by the Baltimore City Public Schools (B.C.P.S.) off Harford Road.

St. Vincent de Paul Roman Catholic Church, located in the eastern downtown neighborhood of Jonestown or Old Town, at North Front Street above East Fayette Street, had its ancient Cemetery near the southeast of the future park and borders the golf course. Still owned by the Church, which is located about three miles southwest of the cemetery, it is a seven-acre burial ground for about 2,000 parishioners of mostly Irish, German and Italian descent dating back to the mid-19th century of Baltimoreans. Heavily hit by vandalism during the 1960s, it was officially closed in the early 1980s and has since fallen into disrepair. Cleanup and maintenance of the cemetery began again in mid-2010 under a newly-established supporters and watchdog group, the Friends of St VIncent's Cemetery.[8][9]

Clifton Park became the central area where Maryland National Guard troops were moved in and out of Baltimore during the riots of April 1968 centering in the Jonestown/Old Town commercial district and surrounding rowhouse residential neighborhood along North Gay Street, following the assassination of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.. It was there that the troops camped out during their mission. They guarded the streets against looting during the day and slept at the Park during the night hours. Dallas Arthur, a Maryland National Guard soldier, describes the situation as intense when he relates to roadblocks posted near Clifton Park.

Clifton Park once had a lake as part of the Baltimore City Department of Public Works metropolitan water system, named Lake Clifton Reservoir; this was drained in the late 1960s . On this site, Lake Clifton High School, (now referred to as the "Lake Clifton Campus"), was built and opened in September 1971, which with its distinctive modernistic architecture is the largest school campus in physical size in the Baltimore City Public Schools system and one of the most massive and most expensive in the country built up to that time. Built in response to relieve the long-time overcrowding resulting from the post-World War II "baby boom" of the 1950s-60s, the schools system undertook development, construction and opening three high schools all at the same time. Besides L.C.H.S., the others were Walbrook High School and Southwestern High School. Lake Clifton however seemed troubled from the start and had problems extending through its first decade of service from the early 1970s into the 1980s. The all-girls secondary school of Eastern High School (founded 1844), after its unfortunate 1984 closure of its landmark 1938 Jacobethan/English Tudor-style 'H'-shaped, red-brick building with limestone trim, to the northeast on East 33rd Street and Loch Raven Boulevard (opposite Memorial Stadium) was later merged with the Lake Clifton High School in response to protests from its students, faculty, alumni and many of the surrounding community, because of the increasing amount of deferred maintenance needed on the then half-century old structure and also by that decade, student population in the city public schools was dropping and an agency determined that one of the City's then almost 25 high schools should be closed. For a number of years, the school was then known as "Lake Clifton-Eastern High School" as a historic continuation of the former long-time premier girls school. After another reorganization of the B.C.P.S. and the rearrangement of several schools in the northeast sector of the City, the institution became known as the "Lake Clifton Campus" currently comprises two small schools: Heritage High School and the REACH! Partnership School.[n 2]

Clifton Park is also home to "Real Food Farm", a 6-acre urban sustainable farm managed by Civic Works, Inc. that was started in 2009. The farm aims to increase food access in the neighborhoods around the park, demonstrate the economic potential of urban farming, and provides experiential education opportunities to the students from Heritage, REACH! and other public city schools.[12][n 3]

Clifton Park was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2007.[1]

References

- ↑ Civic Works, Inc.

- ↑ Civic Works, Inc. is the operator and CEO managing the REACH! Partnership School. More information about the schools can be found on the official websites about the schools.[10][11]

- ↑ Real Food Farm is adjacent to the athletic fields. Additional references and information can be found on the webpage "About - in the news"[13] and the "Official website of Real Food Farm".[14] Information relating to Real Food Farm can be found on Lake Clifton Eastern High School article.

External links

- Civic Works, Inc at the Clifton Mansion (accessed and retrieved on May 6, 2012).

- History and description of the park (accessed and retrieved on May 6, 2012).

- Brief description and address (accessed and retrieved on May 6, 2012).

- Map showing the location of the park (accessed and retrieved on October 14, 2007).

- Clifton Mansion at Explore Baltimore Heritage

- Clifton Park, Baltimore City, including photo from 1995 and boundary map, at Maryland Historical Trust

- 1 2 National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 3 Clifton Park. Department of Recreation and Parks, Baltimore.

- ↑ Clifton Park (venues & attractions). Baltimore Fun Guide.

- ↑ Elizabeth Jo Lampl (2005). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Clifton Park" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust. Retrieved 2016-04-01.

- ↑ Hardin, Wayne. "While Indian Searches, Few Seem To Find Him". baltimoresun.com. The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- ↑ "Clifton Park". baltimorecity.gov. City of Baltimore: Department of Recreation and Parks. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- ↑ http://www.abc2news.com/dpp/news/region/baltimore_city/7-million-clifton-mansion-renovation-project-announced

- ↑ Jacques Kelly (July 18, 2010). "Descendants want unmarked cemetery to be maintained." The Baltimore Sun.

- ↑ Jacques Kelly (September 20, 2010). "Cleanup takes place at neglected cemetery in Clifton Park." The Baltimore Sun.

- ↑ "Official website of Heritage High School". Heritage High School. Retrieved 2012-05-17.

- ↑ "Official website of the REACH! Partnership School". The REACH! Partnership School. Retrieved 2012-05-17.

- ↑ "Hoop Dreams". The Baltimore City Paper. 2009-10-21. Retrieved 2012-05-06.

- ↑ "About - in the news (Real Food Farm)". Real Food Farms. Retrieved 2012-05-17.

- ↑ "Official website of Real Food Farm". Real Food Farm. Retrieved 2012-05-17.