Chronicle of Early Kings

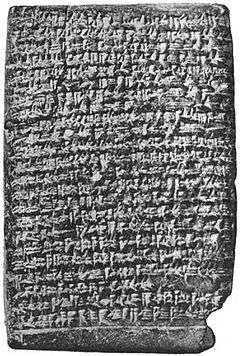

The Chronicle of Early Kings, Chronicle 20 in Grayson’s Assyrian and Babylonian Chronicles[2] and Mesopotamian Chronicle 40 in Glassner’s Chroniques mésopotamiennes[3] is preserved on two tablets, tablet A[i 1] is well preserved whereas tablet B[i 2] is broken and the text fragmentary. Episodic in character, it seems to have been composed from linking together the apodoses of omen literature, excerpts of the Weidner Chronicle and year-names.[4] It begins with events from the late third-millennium reign of Sargon of Akkad and ends, where the tablet is broken away, with that of Agum III, c.a 1500 BC.

A third Babylonian Chronicle Fragment B,[2]:192 Mesopotamian Chronicle 41[3] deals with related subject matter and may be a variant tradition of the same type of work.

The text

Tablet A begins with a lengthy passage concerning the rise and eventual downfall of Sargon of Akkad, caused by his impious treatment of Babylon:

He dug up the dirt of the pit of Babylon and

made a counterpart of Babylon next to Agade.

Because of the wrong he had done the great lord Marduk became angry and

wiped out his people by famine.

They (his subjects) rebelled against him

from east to west

and he (Marduk) afflicted [him] with insomnia.[2]:153–154— from Chronicle of Early Kings Tablet A, lines 18–23

This seemingly anachronous reference to Babylon reproduces text from the Weidner Chronicle. Little is known of the city of Babylon in the third-millennium with the earliest reference to it coming from a year-name of Šar-kali-šarri, Sargon’s grandson.[5] In contrast, the Chronicle devotes a mere six lines to his nephew, Naram-Sin, and two campaigns against Apišal, a city located in northern Syria,[6]:51–52 and Magan, thought to be in ancient Oman.[6]:436–437 That of Apišal appears as an apodosis to an omen in the Bārûtu, the compendium of sacrificial omens.[7]

Šulgi receives short shrift from Marduk, who wreaks a terrible revenge for his expropriation of the property of Marduk’s temple, the Ésagil, and Babylon, as he “caused (something or other) to consume his body and killed him” in a passage that, despite its perfect state of preservation, remains unintelligible.[2]:154 Erra-Imittī’s legendary tale of his demise and that of Enlil-bāni’s ascendency occupies the next passage, followed by a terse observation that “Ilu-šūma was king of Assyria in time of Su-abu”, who was once identified with Sumu-abum, the founder of the First Dynasty of Babylon until a consideration of the relative chronologies made this identification unlikely.[8] The tablet concludes with the label or mark GIGAM.DIDLI which may have been a scribal catalog reference or alternatively denote continuing disruption, as GIGAM represents ippiru, “strife, conflict.”[9]

Tablet B opens with a duplication of the six lines telling of the demise of Erra-Imittī, followed by a section relating Ḫammu-rāpi’s expedition against Rim-Sin I, whom he brought to Babylon in a ki-is-kap (a ḫúppu), a large basket.[10] Samsu-iluna’s handling of the revolt of Rim-Sin II occupies the next section, but here the text is poorly preserved and the events uncertain until it records the victory of Ilum-ma-ilī, the founder of the Sealand Dynasty, over Samsu-iluna’s army. Abī-Ešuḫ’s damming of the Tigris follows, which fails to contain the wiley Ilum-ma-ilī. The history of the First Babylonian dynasty concludes with the Hittite invasion during the reign of Samsu-ditāna.

The final two passages switch to events in the early Kassite Dynastic period, first with the last king of the Sealand Dynasty, Ea-gamil, fleeing ahead of the invasion of Ulam-Buriaš and then the second invasion led by Agum III.[2]:156

Principal publications

- L. W. King (1907). Chronicles Concerning Early Babylonian Kings: Vol. 2 Texts and Translations. Luzac & Co. pp. 3–24, 113–127. copy and translation

- R W. Rogers (1912). "A Chronicle Concerning Sargon and Other Early Babylonian and Assyrian Rulers". Cuneiform Parallels to the Old Testament. Oxford University Press. pp. 203–208. normalization and translation

- E. Ebeling (1926). Altorientalische Texte zum Alten Testament (AOTAT). de Gruyter. pp. 335–337. translation

- A. L. Oppenheim (1955). "Babylonian and Assyrian Historical Texts: The Sargon Chronicle". In James B. Pritchard. Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament (ANET). Princeton University Press. pp. 266–267. translation

- A. K. Grayson (1975). Assyrian and Babylonian Chronicles. J. J. Augustin. pp. 152–156. transliteration and translation

- Jean-Jacques Glassner (1993). Chroniques mésopotamiennes. La Roue à Livres. pp. 268–272. transliteration and translation

External links

- Chronicle of Early Kings at Livius

Inscriptions

References

- ↑ L. W. King (1907). Chronicles Concerning Early Babylonian Kings: Vol. I. Luzac & Co. p. iv.

- 1 2 3 4 5 A. K Grayson (1975). Assyrian and Babylonian Chronicles. J. J. Augustin.

- 1 2 Jean-Jacques Glassner (1993). Chroniques mésopotamiennes. La Roue à Livres.

- ↑ A. K. Grayson (1980). "Assyria and Babylonia". Orientalia. 49: 180–181. JSTOR 43074973.

- ↑ W. G. Lambert (2011). "Babylon: Origins". In Eva Cancik-Kirschbaum, Margarethe Van Ess. Babylon: Wissenskultur in Orient und Okzident. Walter de Gruyter. p. 71.

- 1 2 Trevor Bryce (2009). The Routledge Handbook of The Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia. Routledge.

- ↑ A. R. George (2010). "The Sign of the Flood and the Language of Signs in Babylonian Omen Literature". Proceedings of the 53e Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale, Vol. 1: Language in the Ancient Near East, part 1. Eisenbrauns. p. 328.

- ↑ D. O. Edzard (1957). Zweite Zwischenzeit Babyloniens. Otto Harrassowitz. pp. 140–141.

- ↑ Klaus-Peter Adam (2010). "Warfare and Treaty Formulas in the Background of Kings". In edited by Klaus-Peter Adam, Mark Leuchter. Soundings in Kings: Perspectives and Methods in Contemporary Scholarship. Fortress Press. p. 174. note 82

- ↑ CAD Ḫ, Ḫuppu A, p. 238.