Christine Chapel

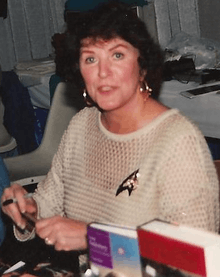

Promotional image of Majel Barrett as Christine Chapel in Star Trek: The Original Series | |

| Species | Human |

|---|---|

| Affiliation | Starfleet |

| Posting |

USS Enterprise nurse, doctor Starfleet Command |

| Rank |

Ensign Lieutenant |

| Portrayed by | Majel Barrett |

| First appearance | "The Naked Time" |

Christine Chapel is a fictional character who appears in all three seasons of the American science fiction television series Star Trek: The Original Series, as well as Star Trek: The Animated Series and the films Star Trek: The Motion Picture and Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home. Portrayed by Majel Barrett, she was the ship's nurse on board the Starfleet starship USS Enterprise. Barrett had previously been cast under her real name as Number One in the first pilot for the series, "The Cage", due in part to her romantic relationship with the series creator Gene Roddenberry. But following feedback from the Network executives, she was not in the cast for the second pilot.

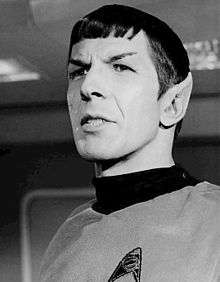

The character made her first appearance in "The Naked Time" following a re-write of the script by Roddenberry. He had been inspired after Barrett read a proposal for the episode "What Are Little Girls Made Of?" and bleached her hair blonde to better fit a role in that episode. The change of color caused Roddenberry to believe that NBC executives might not notice that Barrett had returned against their wishes. The executives immediately recognized Barrett. The character was featured in several episodes covering several broad themes, such as showing her feelings for Spock (Leonard Nimoy), and why she joined Starfleet. By the time of The Motion Picture, Chapel was a Doctor and during the events of The Voyage Home, she was stationed at Starfleet Command.

Executive producer Robert H. Justman was initially critical of Barrett’s performance as Chapel, but recanted this opinion after her appearance as Lwaxana Troi in the Star Trek: The Next Generation. Barrett herself was not fond of the Chapel character, and David Gerrold felt that she only served to demonstrate Spock's emotionless behavior. Critics saw the character as being a degradation for Barrett compared to her first character. While the position of nurse was seen as a stereotype, the character's promotion to doctor was praised. Certain episodes featuring her were criticized, such as "Amok Time" where the plot prevented her from having a relationship with Spock, and "What Are Little Girls Made Of?" where it was suggested she was featured to the detriment of other characters. Among fans, she was initially unpopular due to her feelings for Spock, but prior to the 2009 film Star Trek, there was a desire to see her return.

Concept and development

Prior to working on Star Trek, Gene Roddenberry had been developing a variety of television pilots for Screen Gems. One actress he auditioned was Majel Leigh Hudec, later to use the name Majel Barrett.[1] Later when he created the drama series The Lieutenant, he cast her in the episode "In the Highest Tradition". They quickly became friends, and entered into a romantic relationship although Roddenberry was married at the time.[2][3] During the development of the first pilot for Star Trek: The Original Series ("The Cage"), Roddenberry wrote the part of Number One (the ship’s second in command) specifically for Barrett.[1][4] There was reluctance from the NBC executives to agree to an actress who was almost unknown.[5] Roddenberry did see other actresses for the part, but no one else was considered.[4]

Executive producer Herbert Franklin Solow attempted to sell them on the idea that a fresh face would bring believability to the part, but they were aware that she was Roddenberry's girlfriend. Despite this they agreed to her casting, not wanting to upset Roddenberry at this point in the production.[5] After the pilot was rejected,[6] a second pilot was produced.[7] While it was generally explained that the network disliked a female character as the second-in-command of the Enterprise, Solow had a different opinion of events. He explained that "No one liked her acting... she was a nice woman, but the reality was, she couldn't act."[8] "Where No Man Has Gone Before" successfully took Star Trek to a series order.[9] Barrett had been given the role of voicing the computer on the USS Enterprise, but was demanding that Roddenberry write her into the main cast.[10]

After seeing the initial proposal for "What Are Little Girls Made Of?", Barrett felt that she could play the woman who went into space to find her fiance. She dyed her hair blonde in an attempt to fit the role.[11] Barrett sought to surprise Roddenberry at his office, but he walked right past her, not recognizing who she was. It was only when he came back out give his secretary some papers that he realized it was Barrett. They had the idea that it might get her past the NBC executives and back onto the show.[12] The character of Christine Ducheaux was subsequently changed to Christine Chapel by Roddenberry, as a play on the Sistine Chapel. No other actresses were considered for the role.[10]

At the same time, story editor John D.F. Black wrote the initial script for "The Naked Time", also early in the first season.[13] The story featured a virus being transmitted among the ship's crew, which removed their inhibitions.[14] One element of Black's story featured the addition of a nurse in sickbay, working to Doctor Leonard McCoy.[15] Chapel was written into both these episodes by Roddenberry.[11] The deception didn't work, with NBC executive Jerry Stanley commenting simply "Well, well – look who's back" to Solow.[10] Roddenberry saw to it that the character of Christine Chapel would become a recurring one throughout the series, on-par with Uhura.[10] She remained unsatisfied with the role, but appreciated that since NBC had already fired her once, Roddenberry couldn't expand the role.[16]

For Star Trek: The Animated Series, Barrett was initially set to reprise the role of Chapel as well as voicing Uhura. Likewise James Doohan was to voice both his own Scotty as well as Hikaru Sulu. However, following the intervention of Leonard Nimoy, Nichelle Nichols and George Takei were both brought back to voice their own characters.[17] Barrett returned in Star Trek: The Motion Picture as Chapel, which she described as a "very minimal role",[18] saying that "If no one had called me Commander Chapel, the audience wouldn't really know that I was there."[18] Barrett said in the film franchise Chapel got lost along the way, not appearing in the second or third films despite her view that she was a main character in The Original Series. Nimoy brought back the character for Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home, and Barrett was grateful for his decision.[18] The character was subsequently mentioned in the 2009 film Star Trek,[19] which saw the characters from The Original Series re-cast.[20] Chapel was one of the suggested possibilities for Alice Eve to play in the sequel, Star Trek Into Darkness.[19] It was later revealed that she was portraying Carol Marcus.[21]

Appearances

In "What Are Little Girls Made Of?", it is explained that Chapel abandoned a career in bio-research for a position in Starfleet. She had hoped that this would reunite her with her fiance Dr. Roger Korby (Michael Strong), incommunicado following his expedition to the planet Exo III. Five years after Korby's disappearance, Chapel was assigned to the USS Enterprise, under the command of Captain James T. Kirk. She served as head nurse, working under Dr. McCoy (DeForest Kelley).[22]

While on board the ship, she began to develop feelings for Spock (Leonard Nimoy), admitting as such in "The Naked Time". Her actions in that episode resulted in the Psi 2000 intoxication unwittingly being further spread among the crew.[23] The ship reached Exo III in "What Are Little Girls Made Of?". Captain Kirk (William Shatner) and Chapel beam down and discover Korby had been exploiting a sophisticated android manufacturing technology on the planet. After Chapel is horrified to find out that Korby had transplanted his personality into an android replica, he kills himself in despair.[22] Roddenberry later co-wrote in The Making of Star Trek that the actions of that episode resulted in Chapel breaking her ties to Earth devoting herself to Starfleet service.[24]

After Korby's death, Chapel doubted if she should stay aboard, but elected to remain with the Enterprise throughout the five-year mission.[22] Chapel's feelings for Spock were revisited and alluded to only a few times in the series, most notably in "Plato's Stepchildren". In the episode, the Platonians telekinetically force Chapel and Spock to kiss passionately. This humiliates Chapel despite her long-standing feelings for him.[25] In the episode "Amok Time", she brings Spock some soup to help him through a sacred Vulcan ritual, the Pon farr. He angrily refuses the soup and throws it at the wall, but later thanks Chapel for her thoughtfulness.[26]

Chapel appeared in two of the Star Trek films featuring The Original Series cast. In Star Trek: The Motion Picture, Chapel had become a doctor on board the Enterprise.[18] Her second appearance was in Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home, where she and Janice Rand (Grace Lee Whitney) were stationed in Starfleet Headquarters in San Francisco.[27] In the 2009 film Star Trek, a Nurse Chapel is mentioned by McCoy (Karl Urban). In the 2013 film Star Trek Into Darkness, Carol Marcus (Alice Eve) tells Kirk (Chris Pine) that after being with him, Chapel left to become a nurse.[28]

Reception

Cast and crew

Executive producer Robert H. Justman didn't care for Chapel; he described her as a "wimpy, badly written, and ill-conceived character."[29] He added that the additional camera lenses used by director Jerry Finnerman in that episode for close-ups of her quivering lip only "served to emphasize the lack of character written into the character."[29] He had complained to Roddenberry of Barrett's acting skills, but stopped when he became aware of their relationship. It was only after Barrett's first appearance as Lwaxana Troi in the Star Trek: The Next Generation episode "Haven", that he came to realize that it was the Chapel character he disliked, not Barrett herself and told her that his opinion had changed.[29] Barrett also didn't care for the character of Chapel, saying "I've never been a real aficionado of Nurse Chapel, I figured she was kind of weak and namdy-pamdy."[11]

Writer David Gerrold, who worked with the staff of The Original Series following his work on the episode "The Trouble with Tribbles",[30] described Chapel as being one of a second-tier set of characters including Uhura, Scotty and Sulu, who were not given as much exposure during the series as the main characters of Kirk, Spock and McCoy.[31] He explained that she was the only one of the second level of characters whose motivations were explored, however, her primary focus on board the ship was simply to be in love with Spock. Gerrold explained that there was a need to demonstrate the "aloofness" of the Vulcan character, and so this resulted in a character whose love of him needed to be rebuffed, thus giving Chapel her purpose.[32] He suggested that this caused Chapel to be disliked the fandom because "Female fans saw her as a threat to their own fantasies and male fans saw her as a threat to Spock's Vulcan stoicism."[33] But added that those fans were surprised when they met Barrett at science fiction conventions, as they found her likable in person.[33] By the time of the 2009 film Star Trek, the character had become more popular among fans, who were asking if she would appear in the new films.[28]

Critical reception

In her essay "The Audience as Auteur. Women, Star Trek and 'Vidding'" in the book Gene Roddenberry's Star Trek: The Original Cast Adventures, Francesca Coppa said that she saw the switch from Number One to Chapel for Barrett as "degradation on every level: role, status and image".[34] The role was described as "consolation" in Cary O'Dell's book June Cleaver Was a Feminist!: Reconsidering the Female Characters of Early Television,[35] but it was felt that Barrett "made the most of it".[35] The position of a nurse was described by O'Dell as a traditional female role, but that Chapel would stand up to McCoy's orders when required.[35] Her promotion to Doctor in The Motion Picture was praised by author Gladys L. Knight in her book Female Action Heroes: A Guide to Women in Comics, Video Games, Film, and Television.[36]

Reviewer were critical of her relationship with Spock, with Jan Johnson-Smith describing Chapel in American Science Fiction TV as "a woman condemned to forever lust after the elusive Vulcan", and that she was one of several female characters in the series who were "depicted as recognisable stereotypes".[37] Coppa also discussed this, calling the character as being a typical damsel in distress, existing "merely to pine".[34] But the relationship was also seen positively, with Torie Atkinson, at Tor.com, said of Chapel in "Amok Time" that "her affection is so transparent and sweet."[26] In The Making of Star Trek by Roddenberry and Stephen E. Whitfield, her feelings towards Spock are said to not be unique as they are shared by many of the female crew on board the Enterprise. It is also further explained that McCoy is aware of her feelings, but displays "fatherly affection" towards her and never "childes" her for this.[24]

Her appearances in episodes were commented on, with Wei Ming Dariotis critical that the single-mindedness of the plot for "Amok Time" in not allowing Spock to have sex with Chapel, or any other woman, and thus solve the problem of his Pon farr.[38] But Eugene Myers at Tor.com praised Chapel, saying that the most interesting part of "What Are Little Girls Made Of?" was that it was based primarily on her,[22] while Keith DeCandido said that this resulted in the episode being the "Kirk-and-Chapel show" to the detriment of the other characters.[39]

Notes

- 1 2 Cushman & Osborn (2013): p. 52

- ↑ Shatner & Kreski (1993): p. 14

- ↑ Alexander (1995): pp. 54–55

- 1 2 Alexander (1995): p. 210

- 1 2 Cushman & Osborn (2013): p. 53

- ↑ Cushman & Osborn (2013): p. 65

- ↑ Cushman & Osborn (2013): p. 69

- ↑ Engel (1994): p. 65

- ↑ Cushman & Osborn (2013): p. 101

- 1 2 3 4 Solow & Justman (1996): p. 224

- 1 2 3 Cushman & Osborn (2013): p. 225

- ↑ Dillard & Sackett (1994): p. 21

- ↑ Cushman & Osborn (2013): p. 178

- ↑ Cushman & Osborn (2013): p. 179

- ↑ Cushman & Osborn (2013): p. 183

- ↑ Nazzaro, Joe (May 1997). "Majel Barrett: The First Lady of Star Trek". Star Trek Monthly (27): 42–47.

- ↑ Di Nunzio, Miriam (November 24, 2006). "Animated 'Star Trek' a blast for Takei". Chicago Sun-Times. HighBeam Research. Retrieved February 6, 2016. (subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 3 4 Greenberger, Robert (March 1987). "Majel Barrett Roddenberry: A Woman of Enterprise". Starlog (116): 16–18. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- 1 2 Enk, Bryan (December 6, 2012). "Does the Enterprise sink – and does Spock die – in 'Star Trek Into Darkness'?". Yahoo! News. Archived from the original on February 6, 2016. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ↑ Kamen, Matt (November 2, 2015). "Star Trek is finally returning to television". Wired. Archived from the original on February 7, 2016. Retrieved February 7, 2016.

- ↑ Goldberg, Matt (December 11, 2012). "Alice Eve's Character in Star Trek Into Darkness Revealed". Collider.com. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Myers, Eugene; Atkinson, Torie (April 28, 2009). "Star Trek Re-watch: "What Are Little Girls Made Of?"". Tor.com. Archived from the original on February 7, 2016. Retrieved February 7, 2016.

- ↑ DeCandido, Keith (April 15, 2015). "Star Trek The Original Series Rewatch: "The Naked Time"". Tor.com. Archived from the original on January 28, 2016. Retrieved February 7, 2016.

- 1 2 Whitfield & Roddenberry (1971): p. 254

- ↑ Mack, David; Ward, Dayton (December 9, 2010). "Star Trek Re-watch: "Plato's Stepchildren"". Tor.com. Archived from the original on June 24, 2015. Retrieved February 7, 2016.

- 1 2 Myers, Eugene; Atkinson, Torie (September 1, 2009). "Star Trek Re-Watch: "Amok Time"". Tor.com. Archived from the original on January 24, 2016. Retrieved February 7, 2016.

- ↑ Meyer, Nicholas; Flinn, Dennis Martin (1991). Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country (Film). Paramount Pictures.

- 1 2 Vary, Adam B. (May 19, 2013). "10 Classic Star Trek References In "Star Trek Into Darkness"". Buzzfeed. Archived from the original on January 12, 2015. Retrieved February 7, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Solow & Justman (1996): p. 225

- ↑ Vinciguerra, Thomas (December 16, 2007). "Nobody Knows the Tribbles He's Seen". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 15, 2015. Retrieved February 7, 2016.

- ↑ Gerrold (1974): p. 27

- ↑ Gerrold (1974): p. 29

- 1 2 Gerrold (1974): p. 30

- 1 2 Coppa (2015): p. 169

- 1 2 3 O'Dell (2013): p. 194

- ↑ Knight (2010): p. 188

- ↑ Johnson-Smith (2005): p. 80

- ↑ Dariotis (2008): p. 68

- ↑ DeCandido, Keith (May 12, 2015). "Star Trek The Original Series Rewatch: "What Are Little Girls Made Of?"". Tor.com. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved February 7, 2016.

References

- Alexander, David (1995). Star Trek Creator: The Authorized Biography of Gene Roddenberry. New York: Roc. ISBN 0-451-45440-5.

- Coppa, Francesca (2015). Brode, Douglas; Brode, Shea T., eds. "The Audience as Auteur. Women, Star Trek and "Vidding"". Gene Roddenberry's Star Trek: The Original Cast Adventures. Boulder; New York: Lanham. ISBN 978-1-442-24987-5.

- Cushman, Marc; Osborn, Susan (2013). These are the Voyages: TOS, Season One. San Diego, CA: Jacobs Brown Press. ISBN 978-0-9892381-1-3.

- Dariotis, Wei Ming (2008). Geralty, Lincoln, ed. "Crossing the Racial Frontier: Star Trek and Mixed Heritage Identities". The Influence of Star Trek on Television, Film and Culture. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-786-43034-5.

- Dillard, J.M.; Sackett, Susan (1994). Star Trek: Where No One Has Gone Before. New York: Pocket Books. ISBN 978-0-671-51149-4.

- Engel, Joel (1994). Gene Roddenberry: The Myth and the Man Behind Star Trek. New York: Hyperion. ISBN 0-7868-6004-9.

- Gerrold, David (1974). The World of Star Trek (3rd ed.). New York: Ballatine Books.

- Johnson-Smith, Jan (2005). American Science Fiction TV. London; New York: IB Taurus & Co. ISBN 1-86064-882-7.

- Knight, Gladys L. (2010). Female Action Heroes: A Guide to Women in Comics, Video Games, Film, and Television. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-37613-9.

- O'Dell, Cary (2013). June Cleaver Was a Feminist!: Reconsidering the Female Characters of Early Television. McFarland: Jefferson, NC. ISBN 978-0-786-47177-5.

- Shatner, William; Kreski, Chris (1993). Star Trek Memories. New York: HarperCollinsPublishers. ISBN 978-0-060-17734-8.

- Solow, Herbert F.; Justman, Robert H. (1996). Inside Star Trek: The Real Story. New York: Pocket Books. ISBN 978-0-671-89628-7.

- Whitfield, Stephen E.; Roddenberry, Gene (1971). The Making of Star Trek (7th ed.). New York: Ballantine Books.