Christian mythology

Christian mythology is the body of myths associated with Christianity.

Christian attitudes

In ancient Greek, muthos, from which the English word "myth" derives, meant "story, narrative." Early Christians contrasted their sacred stories with "myths", by which they meant false and pagan stories.[1][2][3]

A number of modern Christian writers such as C.S. Lewis have described elements of Christianity, particularly the story of Christ, as "myth" which is also "true" ("true myth").[4][5][6] Opposition to the term "myth" stems from a variety of sources: the association of the term "myth" with polytheism,[7][8][9] the use of the term "myth" to indicate falsehood or non-historicity,[7][8][10][11][12] and the lack of an agreed-upon definition of "myth".[7][8][12]

As examples of Biblical myths, Every cites the creation account in Genesis 1 and 2 and the story of Eve's temptation.[13] Many Christians believe parts of the Bible to be symbolic or metaphorical (such as the Creation in Genesis).[14]

Historical development

Old Testament

Mythic patterns such as the primordial struggle between good and evil appear in passages throughout the Hebrew Bible, including passages that describe historical events.[15] A distinctive characteristic of the Hebrew Bible is the reinterpretation of myth on the basis of history, as in the Book of Daniel, a record of the experience of the Jews of the Second Temple period under foreign rule, presented as a prophecy of future events and expressed in terms of "mythic structures" with "the Hellenistic kingdom figured as a terrifying monster that cannot but recall [the Near Eastern pagan myth of] the dragon of chaos".[15]

Mircea Eliade argues that the imagery used in some parts of the Hebrew Bible reflects a "transfiguration of history into myth".[16] For example, Eliade says, the portrayal of Nebuchadnezzar as a dragon in Jeremiah 51:34 is a case in which the Hebrews "interpreted contemporary events by means of the very ancient cosmogonico-heroic myth" of a battle between a hero and a dragon.[17]

According to scholars including Neil Forsyth and John L. McKenzie, the Old Testament incorporates stories, or fragments of stories, from extra-biblical mythology.[18][19] According to the New American Bible, a Catholic Bible translation produced by the Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, the story of the Nephilim in Genesis 6:1-4 "is apparently a fragment of an old legend that had borrowed much from ancient mythology", and the "sons of God" mentioned in that passage are "celestial beings of mythology".[20] The New American Bible also says that Psalm 93 alludes to "an ancient myth" in which God battles a personified Sea.[21] Some scholars have identified the biblical creature Leviathan as a monster from Canaanite mythology.[n 1][n 2] According to Howard Schwartz, "the myth of the fall of Lucifer" existed in fragmentary form in Isaiah 14:12 and other ancient Jewish literature; Schwartz claims that the myth originated from "the ancient Canaanite myth of Athtar, who attempted to rule the throne of Ba'al, but was forced to descend and rule the underworld instead".[22]

Some scholars have argued that the calm, orderly, monotheistic creation story in Genesis 1 can be interpreted as a reaction against the creation myths of other Near Eastern cultures.[n 3][n 4] In connection with this interpretation, David and Margaret Leeming describe Genesis 1 as a "demythologized myth",[23] and John L. McKenzie asserts that the writer of Genesis 1 has "excised the mythical elements" from his creation story.[24]

Perhaps the most famous topic in the Bible that could possibly be connected with mythical origins[25] is the topic of Heaven (or the sky) as the place where God (or angels, or the saints) resides,[26][27][28][29][30] with stories such as the ascension of Elijah (who disappeared in the sky),[31][32] war of man with an angel, flying angels.[33][34][35][36][37] Even in the New Testament Saint Paul is said to have visited the third heaven,[38][39] and Jesus was portrayed in several books as going to return from Heaven on a cloud, in the same way He ascended thereto.[40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54] The official text repeated by the attendees during Roman Catholic mass (the Apostles' Creed) contains the words "He ascended into Heaven, and is Seated at the Right Hand of God, The Father. From thence He will come again to judge the living and the dead".[55][56] Medieval cosmology adapted its view of the Cosmos to conform with these scriptures, in the concept of celestial spheres[57][58][59] (later attacked, amongst others, by Giordano Bruno). Some famous opponents of religion, including John Lennon[60] and Stephen Hawking,[61] mentioned this in their public works.

New Testament and early Christianity

According to a number of scholars, the Christ story contains mythical themes such as descent to the underworld, the heroic monomyth, and the "dying god" (see section below on "mythical themes and types").[62][63][64][65]

Some scholars have argued that the Book of Revelation incorporates imagery from ancient mythology. According to the New American Bible, the image in Revelation 12:1-6 of a pregnant woman in the sky, threatened by a dragon, "corresponds to a widespread myth throughout the ancient world that a goddess pregnant with a savior was pursued by a horrible monster; by miraculous intervention, she bore a son who then killed the monster".[66] Bernard McGinn suggests that the image of the two Beasts in Revelation stems from a "mythological background" involving the figures of Leviathan and Behemoth.[67]

The Pastoral Epistles contain denunciations of "myths" (muthoi). This may indicate that Rabbinic or gnostic mythology was popular among the early Christians to whom the epistles were written and that the epistles' author was attempting to resist that mythology.[n 5][n 6]

The Sibylline oracles contain predictions that the dead Roman Emperor Nero, infamous for his persecutions, would return one day as an Antichrist-like figure. According to Bernard McGinn, these parts of the oracles were probably written by a Christian and incorporated "mythological language" in describing Nero's return.[68]

Middle Ages

According to Mircea Eliade, the Middle Ages witnessed "an upwelling of mythical thought" in which each social group had its own "mythological traditions".[69] Often a profession had its own "origin myth" which established models for members of the profession to imitate; for example, the knights tried to imitate Lancelot or Parsifal.[69] The medieval trouveres developed a "mythology of woman and Love" which incorporated Christian elements but, in some cases, ran contrary to official church teaching.[69]

George Every includes a discussion of medieval legends in his book Christian Mythology. Some medieval legends elaborated upon the lives of Christian figures such as Christ, the Virgin Mary, and the saints. For example, a number of legends describe miraculous events surrounding Mary's birth and her marriage to Joseph.[n 7]

In many cases, medieval mythology appears to have inherited elements from myths of pagan gods and heroes.[70][71] According to Every, one example may be "the myth of St. George" and other stories about saints battling dragons, which were "modelled no doubt in many cases on older representations of the creator and preserver of the world in combat with chaos".[72] Eliade notes that some "mythological traditions" of medieval knights, namely the Arthurian cycle and the Grail theme, combine a veneer of Christianity with traditions regarding the Celtic Otherworld.[69] According to Lorena Laura Stookey, "many scholars" see a link between stories in "Irish-Celtic mythology" about journeys to the Otherworld in search of a cauldron of rejuvenation and medieval accounts of the quest for the Holy Grail.[73]

According to Eliade, "eschatological myths" became prominent during the Middle Ages during "certain historical movements".[74] These eschatological myths appeared "in the Crusades, in the movements of a Tanchelm and an Eudes de l'Etoile, in the elevation of Fredrick II to the rank of Messiah, and in many other collective messianic, utopian, and prerevolutionary phenomena".[74] One significant eschatological myth, introduced by Gioacchino da Fiore's theology of history, was the "myth of an imminent third age that will renew and complete history" in a "reign of the Holy Spirit"; this "Gioacchinian myth" influenced a number of messianic movements that arose in the late Middle Ages.[75]

Renaissance and Reformation

During the Renaissance, there arose a critical attitude that sharply distinguished between apostolic tradition and what George Every calls "subsidiary mythology"—popular legends surrounding saints, relics, the cross, etc.—suppressing the latter.[76]

The works of Renaissance writers often included and expanded upon Christian and non-Christian stories such as those of creation and the Fall. Rita Oleyar describes these writers as "on the whole, reverent and faithful to the primal myths, but filled with their own insights into the nature of God, man, and the universe".[77] An example is John Milton's Paradise Lost, an "epic elaboration of the Judeo-Christian mythology" and also a "veritable encyclopedia of myths from the Greek and Roman tradition".[77]

According to Cynthia Stewart, during the Reformation, the Protestant reformers used "the founding myths of Christianity" to critique the church of their time.[78]

Every argues that "the disparagement of myth in our own civilization" stems partly from objections to perceived idolatry, objections which intensified in the Reformation, both among Protestants and among Catholics reacting against the classical mythology revived during the Renaissance.[79]

Enlightenment

The philosophes of the Enlightenment used criticism of myth as a vehicle for veiled criticisms of the Bible and the church.[80] According to Bruce Lincoln, the philosophes "made irrationality the hallmark of myth and constituted philosophy—rather than the Christian kerygma—as the antidote for mythic discourse. By implication, Christianity could appear as a more recent, powerful, and dangerous instance of irrational myth".[81]

Modern period

Some commentators have categorized a number of modern fantasy works as "Christian myth" or "Christian mythopoeia". Examples include the fiction of C.S. Lewis, Madeleine L'Engle, J.R.R. Tolkien, and George MacDonald.[82][n 8]

In The Eternal Adam and the New World Garden, written in 1968, David W. Noble argued that the Adam figure had been "the central myth in the American novel since 1830".[77][n 9] As examples, he cites the works of Cooper, Hawthorne, Melville, Twain, Hemingway, and Faulkner.[77]

Mythical themes and types

Ascending the mountain

According to Lorena Laura Stookey, many myths feature sacred mountains as "the sites of revelations": "In myth, the ascent of the holy mountain is a spiritual journey, promising purification, insight, wisdom, or knowledge of the sacred".[83] As examples of this theme, Stookey includes the revelation of the Ten Commandments on Mount Sinai, Christ's ascent of a mountain to deliver his Sermon on the Mount, and Christ's ascension into Heaven from the Mount of Olives.[83]

Axis mundi

Many mythologies involve a "world center", which is often the sacred place of creation; this center often takes the form of a tree, mountain, or other upright object, which serves as an axis mundi or axle of the world.[84][85][86] A number of scholars have connected the Christian story of the crucifixion at Golgotha with this theme of a cosmic center. In his Creation Myths of the World, David Leeming argues that, in the Christian story of the crucifixion, the cross serves as "the axis mundi, the center of a new creation".[84]

According to a tradition preserved in Eastern Christian folklore, Golgotha was the summit of the cosmic mountain at the center of the world and the location where Adam had been both created and buried. According to this tradition, when Christ is crucified, his blood falls on Adam's skull, buried at the foot of the cross, and redeems him.[86][87] George Every discusses the connection between the cosmic center and Golgotha in his book Christian Mythology, noting that the image of Adam's skull beneath the cross appears in many medieval representations of the crucifixion.[86]

In Creation Myths of the World, Leeming suggests that the Garden of Eden may also be considered a world center.[84]

Combat myth

Many Near Eastern religions include a story about a battle between a divine being and a dragon or other monster representing chaos—a theme found, for example, in the Enuma Elish. A number of scholars call this story the "combat myth".[88][89][90] A number of scholars have argued that the ancient Israelites incorporated the combat myth into their religious imagery, such as the figures of Leviathan and Rahab,[91][92] the Song of the Sea,[91] Isaiah 51:9-10's description of God's deliverance of his people from Babylon,[91] and the portrayals of enemies such as Pharaoh and Nebuchadnezzar.[93] The idea of Satan as God's opponent may have developed under the influence of the combat myth.[91][94] Scholars have also suggested that the Book of Revelation uses combat myth imagery in its descriptions of cosmic conflict.[90][95]

Descent to the underworld

According to Christian tradition, Christ descended to hell after his death, in order to free the souls there; this event is known as the harrowing of hell. This story is narrated in the Gospel of Nicodemus and may be the meaning behind 1 Peter 3:18-22.[96][n 10] According to David Leeming, writing in The Oxford Companion to World Mythology, the harrowing of hell is an example of the motif of the hero's descent to the underworld, which is common in many mythologies.[65]

Dying god

Many myths, particularly from the Near East, feature a god who dies and is resurrected; this figure is sometimes called the "dying god".[64][97][98] An important study of this figure is James George Frazer's The Golden Bough, which traces the dying god theme through a large number of myths.[99] The dying god is often associated with fertility.[64][100] A number of scholars, including Frazer,[101] have suggested that the Christ story is an example of the "dying god" theme.[64][102] In the article "Dying god" in The Oxford Companion to World Mythology, David Leeming notes that Christ can be seen as bringing fertility, though of a spiritual as opposed to physical kind.[64]

In his 2006 homily for Corpus Christi, Pope Benedict XVI noted the similarity between the Christian story of the resurrection and pagan myths of dead and resurrected gods: "In these myths, the soul of the human person, in a certain way, reached out toward that God made man, who, humiliated unto death on a cross, in this way opened the door of life to all of us."[103]

Flood myths

Many cultures have myths about a flood that cleanses the world in preparation for rebirth.[104][105] Such stories appear on every inhabited continent on earth.[105] An example is the biblical story of Noah.[104][106] In The Oxford Companion to World Mythology, David Leeming notes that, in the Bible story, as in other flood myths, the flood marks a new beginning and a second chance for creation and humanity.[104]

Founding myths

According to Sandra Frankiel, the records of "Jesus' life and death, his acts and words" provide the "founding myths" of Christianity.[107] Frankiel claims that these founding myths are "structurally equivalent" to the creation myths in other religions, because they are "the pivot around which the religion turns to and which it returns", establishing the "meaning" of the religion and the "essential Christian practices and attitudes".[107] Tom Cain uses the expression "founding myths" more broadly, to encompass such stories as those of the War in Heaven and the fall of man; according to Cain, "the disastrous consequences of disobedience" is a pervasive theme in Christian founding myths.[108]

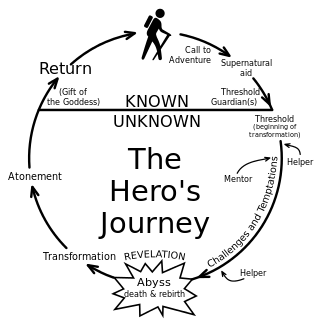

Hero myths

In his influential 1909 work Der Mythus von der Geburt des Helden (The Myth of the Birth of the Hero), Otto Rank argued that the births of many mythical heroes follow a common pattern. Rank includes the story of Christ's birth as a representative example of this pattern.[63]

According to Mircea Eliade, one pervasive mythical theme associates heroes with the slaying of dragons, a theme which Eliade traces back to "the very ancient cosmogonico-heroic myth" of a battle between a divine hero and a dragon.[17] He cites the Christian legend of Saint George as an example of this theme.[109] An example from the later Middle Ages comes from Dieudonné de Gozon, third Grand Master of the Knights of Rhodes, famous for slaying the dragon of Malpasso. Eliade writes:

"Legend, as was natural, bestowed upon him the attributes of St. George, famed for his victorious fight with the monster. […] In other words, by the simple fact that he was regarded as a hero, de Gozon was identified with a category, an archetype, which […] equipped him with a mythical biography from which it was impossible to omit combat with a reptilian monster."[109]

In the Oxford Companion to World Mythology David Leeming lists Moses, Jesus, and King Arthur as examples of the "heroic monomyth",[110] calling the Christ story "a particularly complete example of the heroic monomyth".[62] Leeming regards resurrection as a common part of the heroic monomyth,[110][111] in which the resurrected heroes often become sources of "material or spiritual food for their people"; in this connection, Leeming notes that Christians regard Jesus as the "bread of life".[110]

In terms of values, Leeming contrasts "the myth of Jesus" with the myths of other "Christian heroes such as St. George, Roland, el Cid, and even King Arthur"; the later hero myths, Leeming argues, reflect the survival of pre-Christian heroic values—"values of military dominance and cultural differentiation and hegemony"—more than the values expressed in the Christ story.[62]

Paradise

Many religious and mythological systems contain myths about a paradise. Many of these myths involve the loss of a paradise that existed at the beginning of the world. Some scholars have seen in the story of the Garden of Eden an instance of this general motif.[112][113]

Sacrifice

Sacrifice is an element in many religious traditions and often represented in myths. In The Oxford Companion to World Mythology, David Leeming lists the story of Abraham and Isaac and the story of Christ's death as examples of this theme.[114] Wendy Doniger describes the gospel accounts as a "meta-myth" in which Jesus realizes that he is part of a "new myth [...] of a man who is sacrificed in hate" but "sees the inner myth, the old myth of origins and acceptance, the myth of a god who sacrifices himself in love".[115]

Attitudes toward time

According to Mircea Eliade, many traditional societies have a cyclic sense of time, periodically reenacting mythical events.[116] Through this reenactment, these societies achieve an "eternal return" to the mythical age.[117] According to Eliade, Christianity retains a sense of cyclical time, through the ritual commemoration of Christ's life and the imitation of Christ's actions; Eliade calls this sense of cyclical time a "mythical aspect" of Christianity.[118]

However, Judeo-Christian thought also makes an "innovation of the first importance", Eliade says, because it embraces the notion of linear, historical time; in Christianity, "time is no longer [only] the circular Time of the Eternal Return; it has become linear and irreversible Time".[119] Summarizing Eliade's statements on this subject, Eric Rust writes, "A new religious structure became available. In the Judaeo-Christian religions—Judaism, Christianity, Islam—history is taken seriously, and linear time is accepted. [...] The Christian myth gives such time a beginning in creation, a center in the Christ-event, and an end in the final consummation."[120]

Heinrich Zimmer also notes Christianity's emphasis on linear time; he attributes this emphasis specifically to the influence of Saint Augustine's theory of history.[121] Zimmer does not explicitly describe the cyclical conception of time as itself "mythical" per se, although he notes that this conception "underl[ies] Hindu mythology".[122]

Neil Forsyth writes that "what distinguishes both Jewish and Christian religious systems [...] is that they elevate to the sacred status of myth narratives that are situated in historical time".[123]

Legacy

Concepts of progress

According to Carl Mitcham, "the Christian mythology of progress toward transcendent salvation" created the conditions for modern ideas of scientific and technological progress.[124] Hayden White describes "the myth of Progress" as the "secular, Enlightenment counterpart" of "Christian myth".[125] Reinhold Niebuhr described the modern idea of ethical and scientific progress as "really a rationalized version of the Christian myth of salvation".[126]

Political and philosophical ideas

According to Mircea Eliade, the medieval "Gioacchinian myth [...] of universal renovation in a more or less imminent future" has influenced a number of modern theories of history, such as those of Lessing (who explicitly compares his views to those of medieval "enthusiasts"), Fichte, Hegel, and Schelling, and has also influenced a number of Russian writers.[75]

Calling Marxism "a truly messianic Judaeo-Christian ideology", Eliade writes that Marxism "takes up and carries on one of the great eschatological myths of the Middle Eastern and Mediterranean world, namely: the redemptive part to be played by the Just (the 'elect', the 'anointed', the 'innocent', the 'missioners', in our own days the proletariat), whose sufferings are invoked to change the ontological status of the world".[127]

In his article "The Christian Mythology of Socialism", Will Herberg argues that socialism inherits the structure of its ideology from the influence of Christian mythology upon western thought.[128]

In The Oxford Companion to World Mythology, David Leeming claims that Judeo-Christian messianic ideas have influenced 20th-century totalitarian systems, citing Soviet Communism as an example.[129]

According to Hugh S. Pyper, the biblical "founding myths of the Exodus and the exile, read as stories in which a nation is forged by maintaining its ideological and racial purity in the face of an oppressive great power", entered "the rhetoric of nationalism throughout European history", especially in Protestant countries and smaller nations.[130]

Christmas stories in popular culture

See Secular Christmas stories, Christmas in the media and Christmas in literature.

See also

- Biblical cosmology

- Christian demonology

- Folk Catholicism

- Folk religion

- Christian views on astrology

- Jesus Christ in comparative mythology

- Mormon folklore

Notes

- ↑ In a footnote on Psalm 29:3, the New American Bible identifies Leviathan as "the seven-headed sea monster of Canaanite mythology".

- ↑ Forsyth 65: "[In Job 26:5-14] Yahweh defeats the various enemies of the Canaanite myths, including Rahab, another name for the dragon Leviathan."

- ↑ David and Margaret Leeming contrast the "structured, majestic, logical, somewhat demythologized" creation story in Genesis 1 with the "high-paced, capricious, ritualistic, magic-filled drama" of other Near Eastern creation myths (Leeming, A Dictionary of Creation Myths, 113-14). They add, "One could [...] say this story was written in reaction to creation myths of nearby cultures [...] In other Near Eastern mythologies, the sun and moon are gods who have names and rule. P [i.e. the textual source from which Genesis 1 is drawn] tells of their creation on the fourth day as simply luminaries without name or function except to keep time. [...] While in the Enuma Elish the earth and its inhabitants are created almost haphazardly, as needed, Elohim creates with an unalterable plan in mind" (Leeming, A Dictionary of Creation Myths, 116).

- ↑ John L. McKenzie calls Genesis 1 "a deliberate polemic against the [Near Eastern] creation myth. Polytheism is removed, and with it the theogony and the theomachy which are so vital in the Mesopotamian form of the myth. [...] The act of creation is achieved in entire tranquility" (McKenzie 57).

- ↑ Barrett 69-71 mentions both Rabbinic and gnostic mythology as a possibility.

- ↑ A footnote on 1 Timothy 6:20-21 in the New American Bible refers only to the possibility of gnostic mythology, not of Rabbinic mythology.

- ↑ According to one legend, Anna, Christ's maternal grandmother, initially cannot conceive; in response to Anna's lament, an angel appears and tells her that she will have a child (Mary) who will be spoken of throughout the world (Every 76-77). Some medieval legends about Mary's youth describe her as living "a life of ideal asceticism", fed by angels. In these legends, an angel tells Zacharias, the future father of John the Baptist, to assemble the local widowers; after the widowers have been assembled, some miracle indicates that, among them, Joseph is to be Mary's wife (according to one version of the legend, a dove comes from Joseph's rod and settles on his head) (Every 78).

- ↑ An example of this kind of "mythopoeic" literary criticism can be found in Oziewicz 178: "What L'Engle's Christian myth is and in what sense her Time Quartet qualifies as Christian mythopoeia can thus be glimpsed from both critical assessment of her work and her own reflection as presented in interviews and her voluminous non-fiction."

- ↑ The full title of Noble's book is The Eternal Adam and the New World Garden: The Central Myth in the American Novel since 1830.

- ↑ Every also sees New Testament references to the general resurrection (e.g. in John 5:25-29) as connected with the harrowing of hell, because he believes that early Christianity did not distinguish clearly between the Christ's liberation of souls from hell and the general resurrection (Every 66).

References

- ↑ Eliade, Myth and Reality, 162

- ↑ Oleyar 5

- ↑ Barrett 69

- ↑ Sammons 231

- ↑ Dorrien 236 and throughout

- ↑ Lazo 210

- 1 2 3 Henry, chapter 3

- 1 2 3 Greidanus 23

- ↑ Tyndale House Publishers 9

- ↑ Nwachukwu 47

- ↑ Holman Bible Publishers 896

- 1 2 Hamilton 56-57

- ↑ Every 22

- ↑ Lund, Gerald N. "Understanding Scriptural Symbol". Ensign Oct. 1986 in print. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints https://www.lds.org/, Web. 09 Jan. 2015.

- 1 2 McGinn 18-20

- ↑ Eliade, Cosmos and History, 37

- 1 2 Eliade, Cosmos and History, 38

- ↑ Forsyth 9-10

- ↑ McKenzie 56

- ↑ Footnotes on Revelation 6:1-4 and on Revelation 6:2 in the New American Bible.

- ↑ Footnote on Psalm 93 in the New American Bible

- ↑ Schwartz 108

- ↑ Leeming, A Dictionary of Creation Myths, 116; see also Leeming 115

- ↑ McKenzie 57

- ↑ Ringgren, Helmer (1990). "Yarad". In Botterweck, G. Johannes; Ringgren, Helmer. Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament. Eerdmans.

- ↑ Pennington, Jonathan T. (2007). Heaven and earth in the Gospel of Matthew. Brill.

- ↑ Psalms 68:5

- ↑ Psalms 104:2-4

- ↑ Psalms 29:10

- ↑ Matthew 6:26. Greek original uses the word ουρανού (ouranou, like the Greek god of heavens, Uranus) to describe the birds, the same later to describe the Father. Read here

- ↑ 2 Kings 2:1-12

- ↑ Sirach 48:9-10

- ↑ Isaiah 6:1-8

- ↑ Ezekiel 1:4-2:1

- ↑ Genesis 22:1-18

- ↑ Genesis 28:12

- ↑ Exodus 25:20

- ↑ Lee, Sang Meyng (2010). The Cosmic Drama of Salvation. Mohr Siebeck.

- ↑ 2 Cor 12:1-5

- ↑ Acts 1:1-11

- ↑ Luke 24:50-51

- ↑ Mark 13:26-27

- ↑ Matthew 24:30-31

- ↑ Mark 14:62

- ↑ Luke 21:26-27

- ↑ Matthew 26:64

- ↑ Matthew 17:5-6

- ↑ Mark 9:7-8

- ↑ Luke 9:34-35

- ↑ 1 Thessalonians 4:17

- ↑ Revelation 1:7

- ↑ Revelation 10:1

- ↑ Revelation 11:12

- ↑ Revelation 14:14-16

- ↑

- ↑ Compare also with the Lord's Prayer, a central prayer in Christianity.

- ↑ Edward Grant, Planet, Stars, and Orbs: The Medieval Cosmos, 1200-1687, pp. 382-3, Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr., 1994. ISBN 0-521-56509-X

- ↑ David C. Lindberg, The Beginnings of Western Science, pp. 249-50, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-48231-6

- ↑ See also Wiki articles on Celestial spheres and Giordano Bruno, where 2 scanned cosmographies from medieval books are included. In each one the outermost text reads "The heavenly empire, dwelling of God and all the selected"

- ↑ John Lennon, Imagine

- ↑ Stephen Hawking, A Brief History of Time, c. 1, p. 4 just below the picture, Bantam 1998, ISBN 978-0-553-10953-5

- 1 2 3 Leeming, "Christian Mythology"

- 1 2 Dundes, "The Hero Pattern and the Life of Jesus", 186

- 1 2 3 4 5 Leeming, "Dying God"

- 1 2 Leeming, "Descent to the underworld"

- ↑ Footnote on Revelation 12:1 in the New American Bible.

- ↑ McGinn 54

- ↑ McGinn 47

- 1 2 3 4 Eliade, Myths, Rites, Symbols, vol. 1, 82

- ↑ Every 94, 96

- ↑ Eliade, Myth and Reality, 162-181

- ↑ Every 95

- ↑ Stookey 153

- 1 2 Eliade, Myths, Rites, Symbols, vol. 1, 83

- 1 2 Eliade, Myths, Rites, Symbols, vol. 1, 84-85

- ↑ Every 21

- 1 2 3 4 Oleyar 40-41

- ↑ Stewart 72-73

- ↑ Every 11

- ↑ Lincoln 49

- ↑ Lincoln 50

- ↑ Hein, throughout

- 1 2 Stookey 164

- 1 2 3 Leeming, Creation Myths of the World, 307

- ↑ Eliade, Cosmos and History, 12

- 1 2 3 Every 51

- ↑ Eliade, Myth and Reality, 14

- ↑ McGinn 22

- ↑ Forsyth 126

- 1 2 Murphy 279

- 1 2 3 4 McGinn 24

- ↑ Murphy 281-82

- ↑ Murphy 281

- ↑ Forsyth 124

- ↑ McGinn 57

- ↑ Every 65-66

- ↑ Burkert 99

- ↑ Stookey 99

- ↑ Miles 193-94

- ↑ Stookey 107

- ↑ Miles 194

- ↑ Sowa 351

- ↑ HOMILY OF HIS HOLINESS BENEDICT XVI Saint John Lateran Thursday, 15 June 2006

- 1 2 3 Leeming, "Flood"

- 1 2 Stookey 53

- ↑ Stookey 55

- 1 2 Frankiel 57

- ↑ Cain 84

- 1 2 Eliade, Cosmos and History, 39

- 1 2 3 Leeming, "Heroic monomyth"

- ↑ Leeming, "Resurrection"

- ↑ Leeming, "Paradise myths"

- ↑ Stookey 5, 91

- ↑ Leeming, "Sacrifice"

- ↑ Doniger 112

- ↑ Eliade, Myths, Rites, Symbols, vol. 1, 72-73

- ↑ Wendy Doniger, Forward to Eliade, Shamanism, xiii

- ↑ Eliade, Myths, Rites, Symbols, vol. 1, 78

- ↑ Eliade, Myth and Reality, 65. See also Eliade, Myths, Rites, Symbols, vol. 1, 79

- ↑ Rust 60

- ↑ Zimmer 19

- ↑ Zimmmer 20

- ↑ Forsyth 9

- ↑ Mitcham, in Davison 70

- ↑ White 65

- ↑ Naveh 42

- ↑ Eliade, Myths, Dreams, and Mysteries, in Ellwood 91–92

- ↑ Herberg 131

- ↑ Leeming, "Religion and myth"

- ↑ Pyper 333

Sources

- Barrett, C.K. "Myth and the New Testament: the Greek word μύθος". Myth: Critical Concepts in Literary and Cultural Studies. Vol. 4. Ed. Robert A. Segal. London: Routledge, 2007. 65-71.

- Burkert, Walter. Structure and History in Greek Mythology and Ritual. London: University of California Press, 1979.

- Cain, Tom. "Donne's Political World". The Cambridge Companion to John Donne. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Davison, Aidan. Technology and the Contested Means of Sustainability. Albany: SUNY Press, 2001.

- Doniger, Wendy. Other People's Myths: The Cave of Echoes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

- Dorrien, Gary J. The Word as True Myth: Interpreting Modern Theology. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 1997.

- Dundes, Alan.

- "Introduction". Sacred Narrative: Readings in the Theory of Myth. Ed. Alan Dundes. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984. 1-3.

- "The Hero Pattern and the Life of Jesus". In Quest of the Hero. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990.

- Eliade, Mircea

- Myth and Reality. New York: Harper & Row, 1963 and 1968 printings (See esp. Section IX "Survivals and Camouflages of Myths - Christianity and Mythology" through "Myths and Mass Media")

- Myths, Dreams and Mysteries. New York: Harper & Row, 1967.

- Myths, Rites, Symbols: A Mircea Eliade Reader. Vol. 1. Ed. Wendell C. Beane and William G. Doty. New York: Harper & Row, 1976.

- Cosmos and History: The Myth of the Eternal Return. Trans. Willard R. Trask. New York: Harper & Row, 1959.

- Ellwood, Robert. The Politics of Myth: A Study of C. G. Jung, Mircea Eliade, and Joseph Campbell. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1999.

- Every, George. Christian Mythology. London: Hamlyn, 1970.

- Forsyth, Neil. The Old Enemy: Satan and the Combat Myth. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987.

- Frankiel, Sandra. Christianity: A Way of Salvation. New York: HarperCollins, 1985.

- Greidanus, Sidney. Preaching Christ From Genesis: Foundations for Expository Sermons. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2007.

- Hamilton, Victor P. The Book of Genesis: Chapters 1-17. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1990.

- Hein, Rolland. Christian Mythmakers: C.S. Lewis, Madeleine L'Engle, J.R. Tolkien, George MacDonald, G.K. Chesterton, Charles Williams, Dante Alighieri, John Bunyan, Walter Wangerin, Robert Siegel, and Hannah Hurnard. Chicago: Cornerstone, 2002.

- Henry, Carl Ferdinand Howard. God Who Speaks and Shows: Preliminary Considerations. Crossway: Wheaton, 1999.

- Herberg, Will. "The Christian Mythology of Socialism". The Antioch Review 3.1 (1943): 125-32.

- Holman Bible Publishers. Super Giant Print Dictionary and Concordance: Holman Christian Standard Bible. Nashville, 2006.

- Kirk, G.S. "On Defining Myths". Sacred Narrative: Readings in the Theory of Myth. Ed. Alan Dundes. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984. 53-61.

- Lazo, Andrew. "Gathered Round Northern Fires: The Imaginative Impact of the Kolbítar". Tolkien and the Invention of Myth: A Reader. Ed. Jane Chance. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2004. 191-227.

- Leeming, David Adams.

- "Christian mythology". The Oxford Companion to World Mythology. Oxford University Press, 2004. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. UC - Irvine. 30 May 2011 <http://www.oxfordreference.com/views/ENTRY.html?subview=Main&entry=t208.e334>

- Creation Myths of the World: An Encyclopedia. Second edition. Vol. 1. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2010.

- "Descent to the underworld". The Oxford Companion to World Mythology. Oxford University Press, 2004. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. UC - Irvine. 30 May 2011 <http://www.oxfordreference.com/views/ENTRY.html?subview=Main&entry=t208.e411>

- "Dying god" The Oxford Companion to World Mythology. Oxford University Press, 2004. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. UC - Irvine. 30 May 2011 <http://www.oxfordreference.com/views/ENTRY.html?subview=Main&entry=t208.e469>

- "Flood". The Oxford Companion to World Mythology. Oxford University Press, 2004. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. UC - Irvine. 2 June 2011 <http://www.oxfordreference.com/views/ENTRY.html?subview=Main&entry=t208.e567>

- "Heroic monomyth". The Oxford Companion to World Mythology. Oxford University Press, 2004. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. UC - Irvine. 1 June 2011 <http://www.oxfordreference.com/views/ENTRY.html?subview=Main&entry=t208.e706>

- "Religion and myth". The Oxford Companion to World Mythology. Oxford University Press, 2004. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. UC - Irvine. 2 June 2011 <http://www.oxfordreference.com/views/ENTRY.html?subview=Main&entry=t208.e1348>

- "Resurrection". The Oxford Companion to World Mythology. Oxford University Press, 2004. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. UC - Irvine. 1 June 2011 <http://www.oxfordreference.com/views/ENTRY.html?subview=Main&entry=t208.e1350>

- "Sacrifice". The Oxford Companion to World Mythology. Oxford University Press, 2004. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. UC - Irvine. 1 June 2011 <http://www.oxfordreference.com/views/ENTRY.html?subview=Main&entry=t208.e1380>

- Leeming, David Adams, and Margaret Leeming. A Dictionary of Creation Myths. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994.

- Lincoln, Bruce. Theorizing Myth: Narrative, Ideology, and Scholarship. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999.

- McGinn, Bernard. Antichrist: Two Thousand Years of the Human Fascination With Evil. New York: HarperCollins, 1994.

- McKenzie, John L. "Myth and the Old Testament". Myth: Critical Concepts in Literary and Cultural Studies. Vol. 4. Ed. Robert A. Segal. London: Routledge, 2007. 47-71.

- Miles, Geoffrey. Classical Mythology in English Literature: A Critical Anthology. Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2009.

- Murphy, Frederick James. Fallen is Babylon: The Revelation to John. Harrisburg: Trinity Press International, 1998.

- Naveh, Eyal J. Reinhold Niebuhr and Non-Utopian Idealism: Beyond Illusion and Despair. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2002.

- Nwachukwu, Mary Sylvia Chinyere. Creation-Covenant Scheme and Justification by Faith. Rome: Gregorian University Press, 2002.

- Oleyar, Rita. Myths of Creation and Fall. NY: Harper & Row, 1975.

- Oziewicz, Marek. One Earth, One People: The Mythopoeic Fantasy Series of Ursula K. Le Guin, Lloyd Alexander, Madeleine L'Engle and Orson Scott Card. Jefferson: McFarland, 2008.

- Pyper, Hugh S. "Israel". The Oxford Companion to Christian Thought. Ed. Adrian Hastings. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Ratzinger, Joseph. "Holy Mass and Eucharistic Procession on the Solemnity of the Sacred Body and Blood of Christ: Homily of His Holiness Benedict XVI". Vatican: the Holy See. 31 December 2007 <http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/benedict_xvi/homilies/2006/documents/hf_ben-xvi_hom_20060615_corpus-christi_en.html>.

- Rust, Eric Charles. Religion, Revelation and Reason. Macon: Mercer University Press, 1981.

- Sammons, Martha C. A Far-off Country: A Guide to C.S. Lewis's Fantasy Fiction. Lanham: University Press of America, 2000.

- Schwartz, Howard. Tree of Souls: The Mythology of Judaism. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Sowa, Cora Angier. Traditional Themes and the Homeric Hymns. Wauconda: Bolchazy-Carducci, 2005.

- Stewart, Cynthia. "The Bitterness of Theism: Brecht, Tillich, and the Protestant Principle". Christian Faith Seeking Historical Understanding. Ed. James O. Duke and Anthony L. Dunnavant. Macon: Mercer University Press, 1997.

- Stookey, Lorena Laura. Thematic Guide to World Mythology. Westport: Greenwood, 2004.

- Tyndale House Publishers. NLT Study Bible: Genesis 1-12 Sampler. Carol Stream: Tyndale, 2008.

- White, Hayden. The Content of the Form: Narrative Discourse and Historical Representation. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987.

- Zimmer, Heinrich Robert. Myths and Symbols in Indian Art and Civilization. Ed. Joseph Campbell. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Christian mythology |