Northern Expedition

| Northern Expedition | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Warlord Era, Chinese Civil War | |||||||

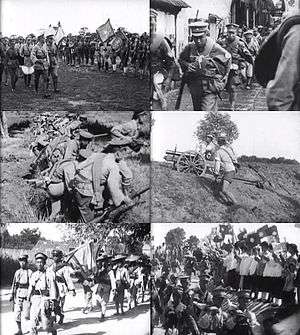

Clockwise from top-left: Chiang inspecting soldiers of the National Revolutionary Army; NRA troops marching northwards; an NRA artillery unit engaged in a battle with warlords; people showing support for the NRA; peasants volunteer to join the expedition; NRA soldiers preparing to launch an attack. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| about 250,000 | about 800,000[1] | ||||||

The Northern Expedition (simplified Chinese: 国民革命军北伐; traditional Chinese: 國民革命軍北伐; pinyin: Guómín gémìng jūn běi fá), was a Kuomintang (KMT) military campaign, led by Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, from 1926–28. Its main objective was to unify China under its own control by ending the rule of the Beiyang government as well as the local warlords. It led to the end of the Warlord Era, the reunification of China in 1928 and the establishment of the Nanjing government.

Preparation

The Northern Expedition, also known as the Northern March, began from the KMT's power base in Guangdong province. In 1925 the May 30th Movement announced plans for a strike and protest against western imperialism and its warlord agents in China. At the same time the First United Front between KMT and the Communist Party of China (CPC) was questioned after the Zhongshan Warship Incident in March 1926, and following events made Chiang Kai-shek in effect the paramount military leader of the KMT. Although Chiang doubted Sun Yat-sen's policy of alliance with the Soviet Union and CPC, he still needed aid from the Soviet Union, so he could not break up the alliance at that time.

Notable military leaders and well-trained soldiers came from the Whampoa Military Academy, which was set up by Sun Yat-sen in 1924. The Academy accepted all persons regardless of party alignment. The success of the Northern Expedition can largely be attributed to both the KMT and CPC working together militarily.[2] This unison, at the time, was strongly encouraged by the Soviet Union, which wanted to see a unified China.

The main targets of this expedition were three notorious and powerful warlords: Zhang Zuolin, who governed Manchuria; Wu Peifu in the Central Plain region; and Sun Chuanfang on the east coast. Advised by the famous Russian Gen. Vasily Blyukher under the pseudonym "Galen", the KMT/CPC commanders of the Expedition decided to use all its power to defeat these warlords one by one: first Wu, then Sun, and finally Zhang.

First Expedition

On July 9, 1926,[3] Chiang gave a lecture to 100,000 soldiers of the National Revolutionary Army (NRA) in a ceremony that was the official commencement of the Northern Expedition. The NRA was set up by cadets trained in the Whampoa Military Academy; its soldiers were far better organized than the warlord armies they faced due to their military advisers and were equipped with Russian and German weapons. In addition, the NRA was regarded as a progressive force on behalf of ordinary people, who were persecuted and mistreated by warlords, and the NRA troops received a warm welcome and strong support from peasants and workers who suffered under the brutal rule of the warlords.[4] It was no surprise the NRA could march from the Zhu River area to the Yangtze River in less than six months and annihilate the main force of Wu and Sun, in addition to increasing its own forces from 100,000 to 250,000.

Purge

Following the defeat of the Zhili clique, Chiang decided to purge all Communists from the Kuomintang. In the Shanghai massacre of April 12, thousands of Communists were executed or went missing, while others were arrested and imprisoned. The purge caused a split between the KMT's left and right wings. The leftists, led by Wang Jingwei in the KMT capital at Wuhan, condemned Chiang's purge. Chiang, however, subsequently established his own capital in Nanjing. As a result, the Nationalist party and its military forces were in a state of disarray during the summer of 1927.

Warlord counteroffensive

The purge gave the warlords an opportunity to rebuild their armies and counter the now weakened Kuomintang. Sun Chuanfang began to marshal his forces with his ally Xu Kun, one of China's best generals. At the same time Sun was communicating with Zhang Zuolin of Manchuria, requesting assistance of any kind in the hopes of regaining his lost territory, including Nanjing. He brought up an army of 100,000 men and arranged them around the Lower Yangtze River. His plan was to begin an all-out attack on the Nationalist forces of Chiang, Li Zongren and Bai Chongxi, drive them away from the Yangtze and Nanjng and pursue them southward back into Guangzhou, where the expedition had started.

Opposing the rejuvenated warlord armies were three Kuomintang Armies, referred to as the "Route Armies": the First Route Army, north of Nanjing in Jiangsu Province; the Second Route, to the west of the First and centered on the city of Xuzhou; and the Third on the west of Xuzhou closer to Wuhan in the south, protecting against any intervention by the leftist Wuhan forces. The Nationalists were able to muster the same amount of manpower but were riven by political tensions and leadership conflicts. In addition, Sun and Xu Kun had the element of surprise on their side, for their attack was not fully expected by Chiang or his commanders. Finally, the Nationalists had stationed many of their troops north of the Yangtze in order to hold Xuzhou, leaving them exposed to the warlord armies and their impending counteroffensive. Thus, many of Chiang's troops were in exposed and isolated positions that they could not defend properly, or with purpose. The stage was set for the last great struggle of the Warlord Era.

On July 24 Sun Chuanfang ordered the counterattack to begin. His army, including Xu Kun's forces, tore through the surprised Nationalist troops, resulting in the loss of Xuzhou in northern Jiangsu province. The Second Route Army, stationed in the area, was forced to withdraw south, using the Long-Hai railway as an escape route. The other Route Armies also began to retreat south toward the Yangtze as the warlord armies routed any remaining troops in their path. Chiang, who was astounded to hear that Xuzhou had fallen, sacked the army's commander, Wang Tianpei. Chiang ordered that Xuzhou be retaken, against the advice of Li Zongren, who thought it was better to withdraw south. Chiang exclaimed, "I will not return to Nanjing until Xuzhou is back in our possession." He launched his attack with the Second Route Army in August, which resulted in a devastating defeat for the Nationalists. This led to Chiang's resignation on Aug. 6 as head of the Nanjing government, prompting him to move to Shanghai, where his loyal supporters followed. Following this, Li Zongren and other military leaders evacuated the entire army to the Yangtze, with the principal goal of defending Nanjing.

Nationalist rapprochement

Li Zongren, the de facto leader of the Nanjing government, set out to negotiate a possible reconciliation between the Wuhan Government (Wang Jingwei) and Nanjing government (Chiang Kai-shek/Jiang Jieshi). The talks, however, were interrupted on Aug. 24 when Sun's troops, supported by Wuhan dissenters, attacked the warship in the Yangtze on which Li was staying. Still, the talks had succeeded in getting Wuhan to cooperate with the Nanjing government. Wang Jingwei, upon the end of negotiations, ordered the purging of all Communists in Wuhan. This sparked a counter-coup by Communist troops in Nanchang, Jiangxi Province, resulting in the deaths of 8,000 Nationalist troops, while many others fled. This chaos in Wuhan contributed to its destabilization and the strengthening of the Nanjing government.

Battle of Longtan

On August 25 Sun Chuanfang's army, now close to the Yangtze, launched an all-out attack on the Nationalist Forces. The worst hit was the First Route Army, defending the strategically placed area of Longtan, vital to the supply of Nanjing via Shanghai. The battle raged around Longtan, especially on Mt. Wulongshan, where Nationalist troops stubbornly held out far longer than was expected, assuring that Sun could not continue his advance to Nanjing. Bai Chongxi, recognizing the importance of Longtan, ordered reinforcements brought up as quickly as possible. Units of the Seventh and 19th Corps arrived on the scene on August 28 and pushed Sun's battered army back to Longtan, relieving Mt. Wulongshan's defenders and buying time for further troops to arrive. On August 30 the full might of the Second Route Army attacked Longtan and, by late afternoon had recaptured the city. Sun's army, with losses equal to two-thirds of its original strength, fled across the Yangtze in defeat.

Second Expedition

The period between September and November was calm and the Nationalists, once more led by the reinstated Chiang Kai-shek, reorganized themselves, though it was not until January 2 that this was formally announced. The Wuhan government, finally bowing to pressure, reconciled itself with Chiang and formally merged with the Nanjing government. On December 12 Nationalist forces, after reoccupying most of the territory lost that summer, recaptured Xuzhou. In response, Zhang Zuolin ordered that all loyal troops join his Anguo-jun Army, which had formed in response to the losses incurred by Sun Chuanfang's counteroffensive. However, it was not until April 2, following the conclusion of the Fourth Meeting of the Congress of the Kuomintang, that Chiang ordered the beginning of the Second Expedition.

The Nationalists swept across the remains of Sun Chuanfang's and Xu Kun's Zhili Clique forces and reached the Yellow River in mid-April, 1928. When Yan Xishan declared his intention to take Beijing, Zhang decided it was best to evacuate. On June 4 Zhang, who was heading north from Beijing by train, was assassinated by Japanese conspirators, operating from Japan's Kwantung Army. Yan's forces occupied Beijing and the city was renamed "Beiping" or "Northern Peace". Zhang's son, Zhang Xueliang, took control of Manchuria and decided to cooperate with Chiang and the Kuomintang, replacing all banners of the Beiyang government in Manchuria with the Nationalist government flag, due to his desire to drive Japanese influence out of Manchuria. Thus China was nominally reunited under one government.

Anti-imperialism

During the Nanjing Incident, the Kuomintang took on the western imperialist powers in China, launching an all-out attack against their concessions in many Chinese cities. Chinese forces stormed the consulates of the US, Britain and Japan, looting nearly every foreign property and almost assassinating the Japanese consul. Nationalist forces killed an American, two Britons, one Frenchman, an Italian and a Japanese. Chinese snipers targeted the American consul and the Marines who were guarding him--Chinese bullets flew into Socony Hall where American citizens were hiding out. One Chinese soldier declared, "We don't want money, anyway, we want to kill."[5] The Kuomintang forces also stormed and seized millions of dollars worth of British concessions in Hankou, refusing to hand them back to Britain. Britain then decided to give them up.[6]

Manchuria

In 1928 Chinese Muslim Gen. Bai Chongxi led Kuomintang forces that defeated and destroyed the army of Fengtian Clique Gen. Zhang Zongchang, capturing 20,000 of his 50,000 troops and almost capturing Zhang himself, who escaped to Manchuria.[7]

Bai personally had around 2,000 Muslims under his control during his stay in Beijing in 1928 after the Northern Expedition was completed. It was reported by TIME magazine that they "swaggered riotously" in the aftermath[8] Bai Chongxi announced in Beijing in June 1928 that the forces of the Kuomintang would seize control of Manchuria, and the enemies of the Kuomintang would "scatter like dead leaves before the rising wind". Gen. Bai was nicknamed "The Hewer of Communist Heads".[9]

Outcome

The Northern Expedition is viewed positively in China today because it ended a period of disorder and started the formation of an effective central government.[10] However, it did not fully solve the warlord problem, as many warlords still had large armies that served their own needs, not those of China. The left wing at the time criticized Soviet leader Joseph Stalin for relying on Chiang, a "bourgeois" figure who betrayed the "proletariat." This view was presented in an influential narrative by Harold Isaacs in his book, The Tragedy of the Chinese Revolution, the 1938 edition of which included a preface by Leon Trotsky.

The only faction destroyed during the expedition was the Zhili clique. Local provincial warlords who seized or enhanced their power included Li Zongren of the New Guangxi Clique, Yan Xishan of the Shanxi clique, Feng Yuxiang and his Northwestern or Guominjun Clique, Tang Shengzhi in Hunan, Chiang Kuang-Nai in Fujian, Sheng Shicai of Xinjiang, Long Yun of Yunnan, Wang Jialie of Guizhou, Liu Xiang and Liu Wenhui of the Sichuan Clique, Han Fuqu of Shandong, Bie Tingfang (别廷芳) of Henan, the Ma Clique of Ma Bufang and his family in Qinghai, Ma Hongkui in Ningxia, and Ma Zhongying in Gansu, Chen Jitang and his Guangdong Clique, Lu Diping (鲁涤平) of Jiangxi and Jing Yuexiu (井岳秀) of Shaanxi. This was because of their alliance with the Kuomintang. They acted as franchisees of the party, wore NRA uniforms and espoused the party doctrine. With the exception of the Xinjiang and Fengtian cliques, the warlords who survived 1928 tended to have some background in revolutionary circles, some going back to the Tongmenghui era.

The wars between these new warlords claimed more lives than ever in the 1930s. This would prove to be a major problem for the KMT all the way through World War II and the following civil war. Chiang gained the greatest benefit from the expedition, however, for the victory achieved his personal goal of becoming paramount leader. Furthermore, he made the military command superior to KMT party leadership, which resulted in his dictatorship later.

It is worth noting that the Northern Expedition was one of only two times in Chinese history when China was united by a conquest from south to north. The other time was when the Ming Dynasty succeeded in expelling the Mongol-Yuan Dynasty from China. The Northern Expedition opened the way for another war between the Kuomintang and Guominjun during the Muslim conflict in Gansu (1927–30).

Trotsky and Stalin

The Northern Expedition became a point of contention over foreign policy between Joseph Stalin and Leon Trotsky. Stalin followed an opportunist policy, ignoring Communist ideology when necessary. He told the CCP to stop complaining about the lower classes and follow the KMT's orders. Stalin believed that the KMT middle and upper classes would defeat the western imperialists in China and complete the revolution. Trotsky wanted the Communist party to complete an orthodox proletarian revolution and opposed the KMT. Stalin funded the KMT during the expedition.[11] Stalin countered Trotskyist criticism by making a secret speech in which he said that Chiang's right-wing Kuomintang were the only ones capable of defeating the imperialists, that Chiang had funding from rich merchants and that his forces were to be utilized until squeezed for all usefulness like a lemon before being discarded. However, Chiang quickly reversed the tables in the Shanghai massacre of 1927 by liquidating the Communist party in Shanghai midway through the Northern Expedition.[12][13]

See also

- National Revolutionary Army

- Whampoa Military Academy

- Chiang Kai-shek

- Military of the Republic of China

- History of the Republic of China

- Sino-German cooperation until 1941

- Central Plains War

- Kuomintang

- Jinan Incident

References

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0R0pR703g7o&ebc=ANyPxKoLuq7Xzgux79YzG0OFnXH5MbXTGpnMe2XVd7BI6rqJGgo3q1PaDA-c2PfWf35ZdhZafdSzisYB05-nqy6yrGdEZhcl2g. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Achieving a third round of CPC-KMT cooperation". http://www.china.org.cn/opinion/2011-10/12/content_23603712.htm. Retrieved 2015-11-27. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ Milly Bennett; A. Tom Grunfeld (1993). On Her Own: Journalistic Adventures from San Francisco to the Chinese Revolution, 1917-1927. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 10–. ISBN 978-1-56324-182-6.

- ↑ 張玉法(1999年):《中華民國史稿》第三章:國 家由分裂走向統一,第152頁。(Chang Yu-fa (1999): History of the Republic of China "Chapter III: Country by the division to unity", p. 152)

- ↑ "Foreign News: NANJING". Time. Apr 4, 1927. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ↑ "CHINA: Japan & France". Time. Apr 11, 1927. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ↑ "CHINA: Potent Hero". Time. Sep 24, 1928. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ↑ "CHINA: Prattling". Time. Sep 3, 1928. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ↑ "CHINA: Nationalist Notes". Time. June 25, 1928. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ↑ 陈祖怀:论“军事北伐,政治南伐—北伐战争时期的一种社会现象

- ↑ Peter Gue Zarrow (2005). China in War and Revolution, 1895–1949. Psychology Press. p. 233. ISBN 0-415-36447-7. Retrieved 2011-01-01.

- ↑ Robert Carver North (1963). Moscow and Chinese Communists. Stanford University Press. p. 96. ISBN 0-8047-0453-8. Retrieved 2011-01-01.

- ↑ Walter Moss (2005). A History of Russia: Since 1855. Anthem Press. p. 282. ISBN 1-84331-034-1. Retrieved 2011-01-01.

External links

- (Chinese) Map of the route of the Northern Expedition

- Republic of China on Taiwan: Armed Forces Museum

- Mehring.com: The Tragedy of The Chinese Revolution

-

Media related to Northern Expedition at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Northern Expedition at Wikimedia Commons