China Airlines Flight 611

|

A China Airlines 747-200 similar to the one involved in the accident, in a previous livery | |

| Accident summary | |

|---|---|

| Date | 25 May 2002 |

| Summary | In-flight break-up due to maintenance error & metal fatigue |

| Site |

20 nautical miles (37 km) northeast of Makung, Penghu Islands, Taiwan Strait 23°59′23″N 119°40′45″E / 23.98972°N 119.67917°ECoordinates: 23°59′23″N 119°40′45″E / 23.98972°N 119.67917°E |

| Passengers | 206 |

| Crew | 19 |

| Fatalities | 225 (all) |

| Survivors | 0 |

| Aircraft type | Boeing 747-209B |

| Operator | China Airlines |

| Registration | B-18255 |

| Flight origin | Taiwan Taoyuan International Airport, Taoyuan, Taiwan |

| Destination | Hong Kong International Airport, Hong Kong |

China Airlines Flight 611 was a regularly scheduled passenger flight from the former Chiang Kai-shek International Airport (now Taiwan Taoyuan International Airport) in Taiwan to Hong Kong International Airport in Hong Kong. On 25 May 2002, the Boeing 747-209B operating the route disintegrated in mid-air due to faulty repairs and crashed into the Taiwan Strait 23 nautical miles (43 km) northeast of the Penghu Islands 20 minutes after takeoff, killing all 225 people on board. The in-flight break-up was caused by improper repairs to the aircraft 22 years earlier. As of January 2016, it remains the most recent accident involving a Boeing 747 to result in passenger fatalities,[note 1] the deadliest accident in Taiwanese history, and the deadliest since the loss of American Airlines Flight 587 in 2001, until the loss of Air France Flight 447(an Airbus A330 ) in 2009.

The accident was particularly disturbing to the public as the Taipei–Hong Kong route was and still is one of the most heavily traveled air routes in the world; it is so profitable that it is even referred to as the "Golden Route".[1]

Flight and disaster

The flight took off at 15:08 local time (07:08 UTC) and was scheduled to arrive at Hong Kong at 16:28 HKT (08:28 UTC). The flight crew consisted of 51-year-old Captain Ching-Fong Yi (Chinese: 易淸豐; pinyin: I Cingfong), 52-year-old First Officer Yea Shyong Shieh (謝亞雄; Syieh Yasyong), and 54-year-old Flight Engineer Sen Kuo Chao (趙盛國; Jhao Shengkuo).[2][3] The names of the pilot and first officer, respectively, are alternatively romanized as "Yi Ching-Fung" and "Hsieh Ya-Shiung".[4] All three pilots were highly experienced airmen – the captain and first officer each had more than 10,100 hours of flying time and the flight engineer had clocked more than 19,100 flight hours.[5]

At 15:16, the flight was cleared to climb to flight level 350 (approximately 35,000 feet (11,000 m)). At 15:33, contact with the plane was lost.[6][7]

Chang Chia-juch, the Taiwanese Vice Minister of Transportation and Communications, said that two Cathay Pacific aircraft in the area received B-18255's emergency location-indicator signals.[8] All 19 crew members and 206 passengers on board the aircraft died.[9]

Passengers

The passengers included a former legislator and two reporters from the United Daily News.[8] The majority of the passengers, 114 people, were members of a Taiwanese group tour to the mainland organized by four travel agencies.[10] Almost all of the passengers were ethnic Chinese. The sole non-ethnic Chinese person was a Swiss man.[6]

Nationalities of the passengers

| Nationality[8] | Passengers | Crew | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 190 | 19 | 209 | |

| 9 | 0 | 9 | |

| 5 | 0 | 5 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Total | 206 | 19 | 225 |

Recovery and identification of remains

The government of the Republic of China kept statistics of the passengers who were recovered.

The remains of 175 of the 206 passengers aboard were recovered and identified.[15] The first 82 bodies, those of 76 passengers and six cabin crew, were found floating on the surface of the ocean, and were recovered by fishing vessels, the Coast Guard, and military vessels.[15]

Autopsies were conducted on three flight crew members, while 10 bodies and some human remains were X-rayed.[15]

Most of the recovered passengers in the rear of the jet (Zones D through E) were found naked, since their clothes were torn off due to the forces of explosive decompression.[15][16] Most of the recovered passengers in the front of the jet (Zones A through C) still had clothes on. Of the recovered passengers, 66 were fully clad, 25 were partially clad and 50 were completely naked.[15]

Some passengers were found floating, while some remained strapped in their seats. Of the recovered passengers, 54 did not float and were not seated, seven did not float and were still seated, 81 floated and did not decompose while 25 floated and decomposed.[15] 92 percent of the passengers initially found floating on the ocean surface had assigned seats located in and between Rows 42 and 57 (Zone E).[15]

Search, recovery and investigation

At 17:05, a military C-130 aircraft spotted a crashed airliner 23 nautical miles (43 km) northeast of Magong, Penghu Islands. Oil slicks were also spotted at 17:05; the first body was found at 18:10.

Searchers recovered 15 percent of the wreckage, including part of the cockpit, and found no signs of burns, explosives or gunshots.

There was no distress signal or communication sent out prior to the crash.[17] Radar data suggests that the aircraft broke into four pieces while at FL350. This theory is supported by the fact that articles that would have been found inside the aircraft were found up to 80 miles (130 km) from the crash site in villages in central Taiwan. The items included magazines, documents, luggage, photographs, Taiwan dollars, and a China Airlines-embossed, blood-stained pillow case.[18][19]

The flight data recorder from Flight 611 shows that the plane began gaining altitude at a significantly faster rate in the 27 seconds before the plane broke apart, although the extra gain in altitude was well within the plane's design limits. The plane was supposed to be leveling off then as it approached its cruising altitude of 35,000 feet. Shortly before the breakup, one of the aircraft's four engines began providing slightly less thrust. Coincidentally, the engine was the only one recovered from the sea floor. Pieces of the aircraft were found in the ocean and on Taiwan, including in the city of Changhua.[20][21]

The governments of Taiwan and the People's Republic of China co-operated in the recovery of the aircraft; the Chinese allowed personnel from Taiwan to search for bodies and aircraft fragments in those parts of the Taiwan Strait controlled by the People's Republic of China.[6][22]

China Airlines requested relatives to submit blood samples for DNA testing at the Criminal Investigation Bureau of National Police Administration (now National Police Agency) and two other locations.[23]

The United Daily News stated that some relatives of passengers described the existence of this flight to Hong Kong as being "unnecessary". Most of the passengers intended to arrive in Mainland China, but because of a lack of direct air links between Taiwan and Mainland China, the travellers had to fly via Hong Kong; the relatives advocated the opening of direct air links between Taiwan and Mainland China,[22] which was eventually realized.

Metal fatigue

The final investigation report found that the accident was the result of metal fatigue caused by inadequate maintenance after a much earlier tailstrike incident. On 7 February 1980, the aircraft was flying from Stockholm Arlanda Airport to Taoyuan International Airport via King Abdulaziz International Airport and Kai Tak International Airport on China Airlines Flight 009. While landing in Hong Kong, part of the plane's tail had scraped along the runway for several hundred feet.[24] The aircraft was depressurized, ferried back to Taiwan on the same day, and a temporary repair done the day after. A more permanent repair was conducted by a team from China Airlines from 23 May through 26 May 1980. However, the permanent repair of the tail strike was not carried out in accordance with the Boeing Structural Repair Manual (SRM). The area of damaged skin in Section 46 was not removed and the repair doubler plate that was supposed to cover in excess of 30 percent of the damaged area did not extend beyond the entire damaged area enough to restore the overall structural strength.

Consequently, after repeated cycles of depressurization and pressurization during flight, the weakened hull gradually started to crack and finally broke open in mid-flight on 25 May 2002, coincidentally 22 years to the day after the faulty repair was made upon the damaged tail. An explosive decompression of the aircraft occurred once the crack opened up, causing the complete disintegration of the aircraft in mid-air.[4] This was not the first time that a plane had crashed because of a faulty repair following a tailstrike. On 12 August 1985, 17 years before the Flight 611 crash and 7 years after the accident aircraft's repair, Japan Airlines Flight 123 had crashed when the vertical stabilizer was torn off and the hydraulic systems severed by explosive decompression, killing 520 of the 524 people on board. That crash had been attributed to a faulty repair to the rear pressure bulkhead, which had been damaged in 1978 in a tailstrike incident.[25] In both crashes, a doubler plate was not installed according to Boeing standards.

China Airlines disputed much of the report, stating that investigators did not find the pieces of the aircraft that would prove the contents of the investigation report.[26]

One piece of evidence of the metal fatigue is contained in pictures that were taken during a routine inspection of the plane years before the crash.[4] The photos showed visible brown nicotine stains around the doubler plate. This nicotine was deposited by smoke from the cigarettes of passengers who were smoking through 1995, when the airline banned inflight smoking.[4] The doubler plate had a brown nicotine stain all the way around it that could have been detected visually by any of the engineers when they inspected the plane. The stain would have suggested that there might be a crack caused by metal fatigue behind the doubler plate, as the nicotine slowly seeped out due to pressure that built up when the plane reached its cruising altitude.[4] The stains were apparently not noticed and no correction was made to the doubler plate. Had an engineer taken notice of the stains, it is likely that the crash would never have happened.[4]

Aircraft history

The aircraft involved, registration B-18255 (originally registered as B-1866), MSN 21843, was the only Boeing 747-200 passenger aircraft left in the China Airlines fleet at the time. It was delivered to the airline in 1979 and had logged 64,810 hours of flight time.[27][28] The aircraft had a 274-seat configuration (22 first-class, 84 business-class, 131 main deck economy-class and 37 upper-deck economy seats). Prior to the crash, China Airlines had sold B-18255 to Orient Thai Airlines for US$1.45 million. The accident flight was the aircraft's penultimate flight for China Airlines as it was scheduled to be delivered to Orient Thai Airlines after its return flight from Hong Kong to Taipei. The contract to sell the aircraft was voided after the crash.[6]

There were only three passenger 747-200s delivered to China Airlines, all from 1979-1980. The other two had been in full passenger service until 1999, when they were converted to freighters. They were immediately grounded by the ROC's Civil Aviation Administration (CAA) after the crash for maintenance checks.[29][30][31]

One of the other 747s also crashed, years later: B-1886, sold to Kalitta Air and re-registered N714CK,[32] operating on behalf of Centurion Air Cargo, crashed in 2008 after suffering a double engine failure on takeoff from Bogotá, Colombia, killing two people on the ground.[33][34]

Note that the seating was also a 3+4+2 seating (9 per row) instead of a standard 747 with 10 seats per row.

The original aircraft planned for CI611 was not supposed to be B-18255, but a Boeing 747-400 registered as B-18272. However, as B-18272 had to be relocated into a different flight temporarily, China Airlines could only use the plane that was under inspection for CI611.

Aftermath

After the crash, in order to express respect for the victims, China Airlines decided that Flight 611 would no longer exist, but that the Taipei-Hong Kong route would continue. The flight number was changed to 619, together with many other flights, including 903, 641, 605 (which was also involved in an accident), 909, 913, 915, 617, 679, 923, 927, 951, 9753 and 2927.

As of 2015, the current flights are 921, 927, 677, 601, 903, 641, 909, 679, 915, 919 and 923.

In addition, a Boeing 737-800 aircraft registered as B-18611 was changed to B-18617 in 2006 for the same reason.

In September 2015, registration number B-1866 was assigned to an Airbus A320-214 (W) with Loong Air (test registration F-WWDE) in April 2, 2014, and the registration number B-18255 (the aircraft registration in CI611) was assigned to an Airbus A330-343X from Singapore Airlines (ex 9V-STJ) due in November 2015 with TransAsia Airways.

Maps

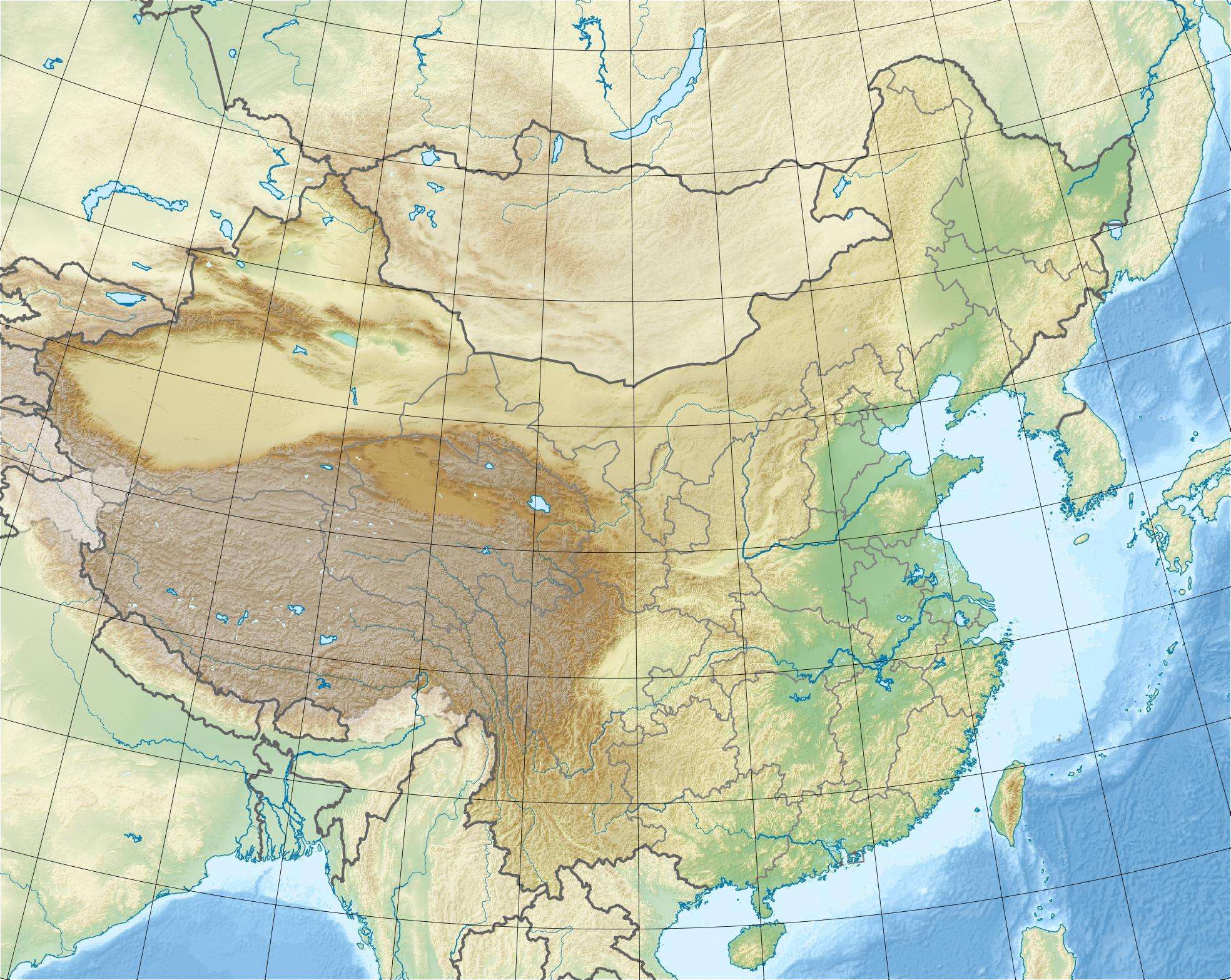

Taipei Hong Kong Crash site Location of the crash and the airports |

Crash site CKS Airport Crash site in Taiwan and departure |

See also

- Aviation safety

- List of accidents and incidents involving commercial aircraft

- List of Mayday episodes "Scratching the Surface"

Notes

- ↑ There have since been non-fatal passenger flight incidents on 747s such as Qantas Flight 30, the non-fatal 747 cargo flight accident Cargolux Flight 7933, and fatalities on 747 cargo flights such as National Airlines Flight 102, MK Airlines Flight 1602 and UPS Airlines Flight 6

References

- ↑ "Shattered in Seconds"("Scratching the Surface") Mayday

- ↑ "NEWS UPDATE OF CHINA AIRLINES CI611 FLIGHT (2)." China Airlines. 25 May 2002. Retrieved on 3 May 2009.

- ↑ "VERSION TIME : 2002/05/28 PM 02:00 CI 611 / 25MAY." China Airlines. 28 May 2002. Retrieved on 3 May 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Credits at end of Mayday episode "Shattered in Seconds" (aka "Scratching the Surface").

- ↑ http://www.zoominfo.com/CachedPage/?archive_id=0&page_id=290797705&page_url=//www.china-airlines.com/us/e_news/2002/20020525b.htm&page_last_updated=2002-06-06T16:57:54&firstName=Ching-Fong&lastName=Yi

- 1 2 3 4 Bhandari, Amit and Ravi Ananthanarayanan. "Catastrophic failure, but how?" (Archive). Times of India. 26 May 2002. Retrieved on 3 May 2009. "All but one of the 225 persons on board the plane were Chinese. Most were from Taiwan, while others came from China, Hong Kong, Macau or Singapore. The only non-Chinese foreigner was Swiss, identified by The Taipei Times" as a Mr Luigi Heer."

- ↑ Bradsher, Keith (25 May 2002). "Taiwanese Airliner With 225 Aboard Crashes in Sea". New York Times. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- 1 2 3 Low, Stephanie and Chang Yu-jung. "CAL 747 crashes with 225 aboard." () Taipei Times. 26 May 2002. Retrieved on 3 May 2009. " All 19 crew members as well as 190 passengers on board were Taiwanese, including two United Daily News reporters and a former legislator. In addition to 14 Hong Kong, Macau and Chinese residents, foreign passengers also included one Singaporean, identified as Sim Yong-joo, and one Swiss, identified as Luigi Heer."

- ↑ Chinoy, Mike (25 May 2002). "All 225 feared dead in Taiwan air crash". CNN. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ↑ "Taiwan's Tragic Air Crash Kills 225 People". People's Daily. 26 May 2002. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- ↑ "Search continues after 747 crashes in Taiwan Strait." (Archive) CBC. 25 May 2002. Retrieved on 3 May 2009. "The passengers list showed most of the people on board were Taiwanese, but also included a Singaporean, five people from Hong Kong, nine Chinese people and one Swiss citizen."

- ↑ "Crashed China Airlines Plane Over 22 Years Old." Xinhua at People's Daily. Sunday 26 May 2002. Retrieved on 3 May 2009.

- ↑ "No distress signal before Taiwan crash." (Archive) CNN. 26 May 2002. Retrieved on 3 May 2009. "China Airlines official Wang Cheng-yu said most of the passengers were from Taiwan but there were two from Singapore, 14 from Hong Kong, Macau or China and one from Europe."

- ↑ "Hope Fades in Taiwan Crash Search." (Archive) BBC. 25 May 2002. Retrieved on 3 May 2009. "Also on board were two Singaporeans, 14 people from Hong Kong, Macau or China and one European."

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "CI611 Accident Investigation Factual Data Collection Group Report" (PDF). TaiwanReport. 3 June 2003. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- ↑ "Decay Under Patches Might Have Caused China Airlines Crash". Aviation Today. 30 June 2003. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ↑ "China missile ruled out in Taiwan crash," CNN – Version with full pictures:

- ↑ "Military aviation expert says flaws in Taiwan plane crash theory: report." The Namibian. Monday 8 July 2002. Retrieved on 3 May 2009.

- ↑ "78 Bodies From Crashed Taiwanese Plane Retrieved". Xinhua News Agency. 26 May 2002. Retrieved 3 May 2009.

- ↑ "Relatives fly to Taiwan crash site". BBC News. 26 May 2002.

- ↑ Gittings, John (25 May 2002). "225 dead in mystery Taiwan crash". The Observer. The Guardian. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- 1 2 Lam, Willy Wo-Lap (27 May 2002). "Crash brings Taiwan, China together". CNN. Retrieved 27 May 2009.

- ↑ "NEWS UPDATE OF B18255 INCIDENT (6)." China Airlines4 August 2002.

- ↑ China Airlines Flight CI-611 Crash Report Released (Report). International Aviation Safety Organisation. 25 February 2005.

- ↑ "Boeing admits bad work on ill-fated Japanese Boeing 747". Star-News. 8 September 1985. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ↑ "China Airlines Statement on CI 611 Accident Investigation Report" (Press release). China Airlines. 25 February 2005. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ↑ "China Airlines". Web.archive.org. Archived from the original on 4 August 2002. Retrieved 22 April 2010.

- ↑ Marshall, Tyler; Tsai, Ting-I (26 May 2002). "Jet Crashes Off Taiwan With 225 People Aboard". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ↑ "ASN Aircraft accident Boeing 747-209B B-18255". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- ↑ Bradsher, Keith (27 May 2002). "Taiwan Airliner Broke Apart in Midair, Investigators Say". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- ↑ "China Airlines Boeing 747s from 1985-1999". Plane Spotters. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- ↑ "FAA Registry". Federal Aviation Administration.

- ↑ "Kalitta Air N714CK (Boeing 747 - MSN 22446) (Ex B-18753 B-1886)". Airfleets.net. Retrieved 2015-03-19.

- ↑ "Crash: Kalitta B742 at Bogota on Jul 7th 2008, engine fire, impacted a farm house". Aviation Herald. 2008-07-11. Retrieved 2015-03-19.

External references

- ASC-AOR-05-02-001, the official Aviation Safety Council documents.

- ASC-AOR-05-02-001, official ASC documents in Chinese

- Chinese language final report, Volume 1 (Archive) – Chinese is the original version and the language of reference

- Chinese language final report, Volume 2 (Archive)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to China Airlines Flight 611. |

|

|

Official investigation reports

China Airlines

Media

- "Cracks blamed for 2002 China Airlines crash", CBC News, 25 February 2005

- Crashed China Airlines Plane Said to Break up in Sky, People's Daily

- "CAL 747 crashes with 225 aboard," Taipei Times

- "China Airlines back in the dock," BBC

- Between the Shores of Life and Death

- Set the Kite Free

- Taiwan says crashed China Air jet missed check-ups

Other

- Cockpit Voice Recorder transcript and accident summary

- B-18255 Seat Plan

- China Airlines flight 611 disaster Tzu Chi mobilizes volunteers from all over Taiwan to help Tzu Chi

- Jiang Expresses Condolence Over Victims of China Airlines Crash (05/27/02)

- (Taiwanese Mandarin) Yang, Minghao (楊明浩), Li Baokang (李寶康), Su Shuikao (蘇水灶), and Guan Wenlin (官文霖). "華航CI-611事故調查地理資訊系統整合" (Archive). Aviation Safety Council. - Includes English abstract