Chimpanzee

| Chimpanzees[1] Temporal range: Middle Pliocene - Recent | |

|---|---|

| |

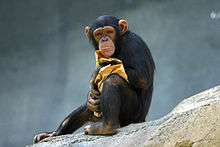

| Common chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Subtribe: | Panina |

| Genus: | Pan Oken, 1816 |

| Type species | |

| Pan troglodytes Blumenbach, 1775 | |

| Species | |

| |

| Distribution of Pan troglodytes (common chimpanzee) and Pan paniscus (bonobo, in red) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Troglodytes E. Geoffroy, 1812 (preoccupied) | |

Chimpanzees (sometimes called chimps) are one of the two species of the genus Pan, the other being the bonobo. Together with gorillas, they are the only exclusively African species of great ape that are currently extant. Native to sub-Saharan Africa, both chimpanzees and bonobos are currently found in the Congo jungle.

Chimpanzee and bonobo: differences and commonalities

They were once considered to be one species, however, since 1928, they have been recognized as two distinct species: the common chimpanzee (P. troglodytes) who live north of the Congo River, and the bonobo (P. paniscus) who live south of it.[2] In addition, P. troglodytes is divided into four subspecies, while P. paniscus has none. Based on genome sequencing, the two extant Pan species diverged around one million years ago. The most obvious differences are that chimpanzees are somewhat larger, more aggressive and male-dominated, while the bonobos are more gracile, peaceful, and female-dominated.

Their hair is typically black or brown. Males and females differ in size and appearance. Both chimps and bonobos are some of the most social great apes, with social bonds occurring among individuals in large communities. Fruit is the most important component of a chimpanzee's diet; however, they will also eat vegetation, bark, honey, insects and even other chimps or monkeys. They can live over 30 years in both the wild and captivity.

Chimpanzees and bonobos are equally humanity's closest living relatives. As such, they are among the largest-brained, and most intelligent of primates; they use a variety of sophisticated tools and construct elaborate sleeping nests each night from branches and foliage. They have both been extensively studied for their learning abilities. There may even be distinctive cultures within populations. Field studies of Pan troglodytes were pioneered by primatologist Jane Goodall. Both Pan species are considered to be endangered as human activities have caused severe declines in the populations and ranges of both species. Threats to wild panina populations include poaching, habitat destruction, and the illegal pet trade. Several conservation and rehabilitation organisations are dedicated to the survival of Pan species in the wild.

Names

The first use of the name "chimpanze" is recorded in The London Magazine in 1738,[3] glossed as meaning "mockman" in a language of "the Angolans" (apparently from a Bantu language, reportedly modern Vili (Civili), a Zone H Bantu language, has the comparable ci-mpenzi[4]). The spelling chimpanzee is found in a 1758 supplement to Chamber's Cyclopædia.[5] The colloquialism "chimp" was most likely coined some time in the late 1870s.[6]

The common chimpanzee was named Simia troglodytes by Johann Friedrich Blumenbach in 1776. The species name troglodytes is a reference to the Troglodytae (literally "cave-goers"), an African people described by Greco-Roman geographers. Blumenbach first used it in his De generis humani varietate nativa liber ("[Book] on the natural varieties of the human genus") in 1776,[7][8] Linnaeus 1758 had already used Homo troglodytes for a hypothetical mixture of human and orangutan.[9]

The genus name Pan was first introduced by Lorenz Oken in 1816. An alternative Theranthropus was suggested by Brookes 1828 and Chimpansee by Voigt 1831. Troglodytes was not available, as it had been given as the name of a genus of wren (Troglodytidae) in 1809. The International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature adopted Pan as the only official name of the genus in 1895.[9] The name is a reference to Pan, the Greek god of nature and wilderness.[10]

The bonobo, in the past also referred to as the "pygmy chimpanzee", was given the species name of paniscus by Ernst Schwarz (1929), a diminutive of the theonym Pan.[11]

In his book, The Third Chimpanzee, J. Diamond proposes that P. troglodytes and P. paniscus belong with H. sapiens in the genus Homo, rather than in Pan. He argues that other species have been reclassified by genus for less genetic similarity than that between humans and chimpanzees.

Distribution and habitat

There are two species of the genus Pan, both previously called Chimpanzees:

- Common Chimpanzees or Pan troglodytes, are found almost exclusively in the heavily forested regions of Central and West Africa. With at least four commonly accepted subspecies, their population and distribution is much more extensive that the Bonobos, in the past also called 'Pygmy Chimpanzee'.

- Bonobos, Pan paniscus, are found only in Central Africa, south of the Congo River and north of the Kasai River (a tributary of the Congo),[12] in the humid forests of the Democratic Republic of Congo of Central Africa.

Evolutionary history

Evolutionary relationship

The genus Pan is part of the subfamily Homininae, to which humans also belong. The lineages of chimpanzees and humans separated in a drawn-out process of speciation over the period of roughly between twelve and five million years ago,[13] making them humanity's closest living relative.[14] Research by Mary-Claire King in 1973 found 99% identical DNA between human beings and chimpanzees.[15] For some time, research modified that finding to about 94%[16] commonality, with some of the difference occurring in noncoding DNA, but more recent knowledge states the difference in DNA between humans, chimpanzees and bonobos at just about 1%-1.2% again.[17][18]

| Taxonomy of genus Pan[1] | Phylogeny of superfamily Hominoidea[19](Fig. 4) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Fossils

The chimpanzee fossil record has long been absent and thought to have been due to the preservation bias in relation to their environment. However, in 2005, chimpanzee fossils were discovered and described by Sally McBrearty and colleagues. Existing chimpanzee populations in West and Central Africa are separate from the major human fossil sites in East Africa; however, chimpanzee fossils have been reported from Kenya, indicating that both humans and members of the Pan clade were present in the East African Rift Valley during the Middle Pleistocene.[20]

Anatomy and physiology

A chimpanzee's arms are longer than its legs. The male common chimp stands up to 1.2 m (3.9 ft) high and weighs as much as 91 kg (201 lb); the female is somewhat smaller. When extended, the common chimp's long arms span one and a half times the body's height.[22] The bonobo is slightly shorter and thinner than the common chimpanzee, but has longer limbs. In trees, both species climb with their long, powerful arms; on the ground, chimpanzees usually knuckle-walk, or walk on all fours, clenching their fists and supporting themselves on the knuckles. Chimpanzees are better suited for walking than orangutans, because the chimp's feet have broader soles and shorter toes. The bonobo has proportionately longer upper limbs and walks upright more often than does the common chimpanzee. Both species can walk upright on two legs when carrying objects with their hands and arms.

The chimpanzee is tailless; its coat is dark; its face, fingers, palms of the hands, and soles of the feet are hairless. The exposed skin of the face, hands, and feet varies from pink to very dark in both species, but is generally lighter in younger individuals and darkens with maturity. A University of Chicago Medical Centre study has found significant genetic differences between chimpanzee populations.[23] A bony shelf over the eyes gives the forehead a receding appearance, and the nose is flat. Although the jaws protrude, a chimp's lips are thrust out only when it pouts.

The brain of a chimpanzee has been measured at a general range of 282–500 cc.[24] The human brain, in contrast, is about three times larger, with a reported average volume of about 1330 cc.[25]

Chimpanzees reach puberty between the age of eight and ten years. A chimpanzee's testicles are unusually large for their body size, with a combined weight of about 4 oz (110 g) compared to a gorilla's 1 oz (28 g) or a human's 1.5 ounces (43 g). This relatively great size is generally attributed to sperm competition due to the polyandrous nature of chimpanzee mating behaviour.[26]

Longevity

One study estimates that chimps live about 33 years for males, 37 years for females, in the wild,[27] but some have lived longer than 60 years in captivity.

Muscle strength

Chimpanzees are known for possessing great amount of muscle strength, especially in their arms. However, compared to humans the amount of strength reported in media and popular science is greatly exaggerated with numbers of four to eight times the muscle strength of a human. These numbers stem from two studies in 1923 and 1926 by a biologist named John Bauman.[28][29] These studies were refuted in 1943 and an adult male chimp was found to pull about the same weight as an adult man.[30] Corrected for their smaller body sizes, chimpanzees were found to be stronger than humans but not anywhere near four to eight times. In the 1960s these tests were repeated and chimpanzees were found to have twice the strength of a human when it came to pulling weights. The reason for the higher strength seen in chimpanzees compared to humans are thought to come from longer skeletal muscle fibers that can generate twice the work output over a wider range of motion compared to skeletal muscle fibers in humans.

Behaviour

Chimpanzee vs. bonobo

Anatomical differences between the common chimpanzee and the bonobo are slight, but sexual and social behaviours are markedly different. The common chimpanzee has an omnivorous diet, a troop hunting culture based on beta males led by an alpha male, and highly complex social relationships. The bonobo, on the other hand, has a mostly frugivorous diet and an egalitarian, nonviolent, matriarchal, sexually receptive behaviour.[31] Bonobos frequently have sex, sometimes to help prevent and resolve conflicts. Different groups of chimpanzees also have different cultural behaviour with preferences for types of tools.[32] The common chimpanzee tends to display greater aggression than does the bonobo.[33] The average captive chimpanzee sleeps 9.7 hours per day.[34]

Contrary to what the scientific name (Pan troglodytes) may suggest, chimpanzees do not typically spend their time in caves, but there have been reports of some of them seeking refuge in caves because of the heat during daytime.[35]

Chimpanzees

Social structure

Chimpanzees live in large multi-male and multi-female social groups, which are called communities. Within a community, the position of an individual and the influence the individual has on others dictates a definite social hierarchy. Chimpanzees live in a leaner hierarchy wherein more than one individual may be dominant enough to dominate other members of lower rank. Typically, a dominant male is referred to as the alpha male. The alpha male is the highest-ranking male that controls the group and maintains order during disputes. In chimpanzee society, the 'dominant male' sometimes is not the largest or strongest male but rather the most manipulative and political male that can influence the goings on within a group. Male chimpanzees typically attain dominance by cultivating allies who will support that individual during future ambitions for power. The alpha male regularly displays by puffing his normally slim coat up to increase view size and charge to seem as threatening and as powerful as possible; this behaviour serves to intimidate other members and thereby maintain power and authority, and it may be fundamental to the alpha male's holding on to his status. Lower-ranking chimpanzees will show respect by submissively gesturing in body language or reaching out their hands while grunting. Female chimpanzees will show deference to the alpha male by presenting their hindquarters.

Female chimpanzees also have a hierarchy, which is influenced by the position of a female individual within a group. In some chimpanzee communities, the young females may inherit high status from a high-ranking mother. Dominant females will also ally to dominate lower-ranking females: whereas males mainly seek dominant status for its associated mating privileges and sometimes violent domination of subordinates, females seek dominant status to acquire resources such as food, as high-ranking females often have first access to them. Both genders acquire dominant status to improve social standing within a group.

Community female acceptance is necessary for alpha male status; females must ensure that their group visits places that supply them with enough food. A group of dominant females will sometimes oust an alpha male which is not to their preference and back another male, in whom they see potential for leading the group as a successful alpha male.

Intelligence

Chimpanzees make tools and use them to acquire foods and for social displays; they have sophisticated hunting strategies requiring cooperation, influence and rank; they are status conscious, manipulative and capable of deception; they can learn to use symbols and understand aspects of human language including some relational syntax, concepts of number and numerical sequence;[36] and they are capable of spontaneous planning for a future state or event.[37]

Tool use

In October 1960, Jane Goodall observed the use of tools among chimpanzees. Recent research indicates that chimpanzees' use of stone tools dates back at least 4,300 years (about 2,300 BC).[38] One example of chimpanzee tool usage behavior includes the use of a large stick as a tool to dig into termite mounds, and the subsequent use of a small stick altered into a tool that is used to "fish" the termites out of the mound.[39] Chimpanzees are also known to use smaller stones as hammers and a large one as an anvil in order to break open nuts.[40]

In the 1970s, reports of chimpanzees using rocks or sticks as weapons were anecdotal and controversial.[41] However, a 2007 study claimed to reveal the use of spears, which common chimpanzees in Senegal sharpen with their teeth and use to stab and pry Senegal bushbabies out of small holes in trees.[42] [43]

Prior to the discovery of tool use in chimps, humans were believed to be the only species to make and use tools; however, now several other tool-using species are now known.[44][45]

Nest-building

Nest-building, sometimes considered to be a form of tool use, is seen when chimpanzees construct arboreal night nests by lacing together branches from one or more trees to build a safe, comfortable place to sleep; infants learn this process by watching their mothers. The nest provides a sort of mattress, which is supported by strong branches for a foundation, and then lined with softer leaves and twigs; the minimum diameter is 5 metres (16 ft) and may be located at a height of 3 to 45 metres (10 to 150 ft). Both day and night nests are built, and may be located in groups.[46] A study in 2014 found that the Muhimbi tree is favoured for nest building by chimpanzees in Uganda due to its physical properties, such as bending strength, inter-node distance, and leaf surface area.[47]

Altruism and emotivity

Studies have shown chimpanzees engage in apparently altruistic behaviour within groups.[48][49] Some researchers have suggested that chimpanzees are indifferent to the welfare of unrelated group members,[50] but a more recent study of wild chimpanzees found that both male and female adults would adopt orphaned young of their group. Also, different groups sometimes share food, form coalitions, and cooperate in hunting and border patrolling.[51] Sometimes, chimpanzees have adopted young that come from unrelated groups. And in some rare cases, even male chimps have been shown to take care of abandoned infant chimps of an unrelated group, though in most cases they would kill the infant.

According to a literature summary by James W. Harrod, evidence for chimpanzee emotivity includes display of mourning; "incipient romantic love"; rain dances; appreciation of natural beauty (such as a sunset over a lake); curiosity and respect towards other wildlife (such as the python, which is neither a threat nor a food source to chimpanzees); altruism toward other species (such as feeding turtles); and animism, or "pretend play", when chimps cradle and groom rocks or sticks.[52]

Communication between chimpanzees

Chimps communicate in a manner that is similar to that of human nonverbal communication, using vocalizations, hand gestures, and facial expressions. There is even some evidence that they can recreate human speech.[53] Research into the chimpanzee brain has revealed that when chimpanzees communicate, an area in the brain is activated which is in the same position as the language center called Broca's area in human brains.[54]

There is some debate as to whether chimpanzees have the ability to express hierarchical ideas in language. Studies have found that chimps are capable of learning a limited set of sign language symbols, which they can use to communicate with human trainers. However, it is clear that there are distinct limits to the complexity of knowledge structures with which chimps are capable of dealing. The sentences that they can express are limited to specific simple noun-verb sequences, and are they do not seem capable of the extent of thought complexity characteristic of humans.

Aggression

Adult common chimpanzees, particularly males, can be very aggressive. They are highly territorial and are known to kill other chimps.[55]

Hunting

Chimpanzees also engage in targeted hunting of lower-order primates, such as the red colobus[56] and bush babies,[57][58] and use the meat from these kills as a "social tool" within their community.[59]

Puzzle solving

In February 2013, a study found that chimpanzees solve puzzles for entertainment.[60]

Chimpanzees in human history

Chimps, as well as other apes, had also been purported to have been known to ancient writers, but mainly as myths and legends on the edge of European and Near Eastern societal consciousness. Apes are mentioned variously by Aristotle. The English word ape translates Hebrew qőf in English translations of the Bible (1 Kings 10:22), but the word may refer to a monkey rather than an ape proper.

The diary of Portuguese explorer Duarte Pacheco Pereira (1506), preserved in the Portuguese National Archive (Torre do Tombo), is probably the first written document to acknowledge that chimpanzees built their own rudimentary tools. The first of these early transcontinental chimpanzees came from Angola and were presented as a gift to Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange in 1640, and were followed by a few of its brethren over the next several years. Scientists described these first chimpanzees as "pygmies", and noted the animals' distinct similarities to humans. The next two decades, a number of the creatures were imported into Europe, mainly acquired by various zoological gardens as entertainment for visitors.

Darwin's theory of natural selection (published in 1859) spurred scientific interest in chimpanzees, as in much of life science, leading eventually to numerous studies of the animals in the wild and captivity. The observers of chimpanzees at the time were mainly interested in behaviour as it related to that of humans. This was less strictly and disinterestedly scientific than it might sound, with much attention being focused on whether or not the animals had traits that could be considered 'good'; the intelligence of chimpanzees was often significantly exaggerated, as immortalized in Hugo Rheinhold's Affe mit Schädel (see image, left). By the end of the 19th century, chimpanzees remained very much a mystery to humans, with very little factual scientific information available.

In the 20th century, a new age of scientific research into chimpanzee behaviour began. Before 1960, almost nothing was known about chimpanzee behaviour in their natural habitats. In July of that year, Jane Goodall set out to Tanzania's Gombe forest to live among the chimpanzees, where she primarily studied the members of the Kasakela chimpanzee community. Her discovery that chimpanzees made and used tools was groundbreaking, as humans were previously believed to be the only species to do so. The most progressive early studies on chimpanzees were spearheaded primarily by Wolfgang Köhler and Robert Yerkes, both of whom were renowned psychologists. Both men and their colleagues established laboratory studies of chimpanzees focused specifically on learning about the intellectual abilities of chimpanzees, particularly problem-solving. This typically involved basic, practical tests on laboratory chimpanzees, which required a fairly high intellectual capacity (such as how to solve the problem of acquiring an out-of-reach banana). Notably, Yerkes also made extensive observations of chimpanzees in the wild which added tremendously to the scientific understanding of chimpanzees and their behaviour. Yerkes studied chimpanzees until World War II, while Köhler concluded five years of study and published his famous Mentality of Apes in 1925 (which is coincidentally when Yerkes began his analyses), eventually concluding, "chimpanzees manifest intelligent behaviour of the general kind familiar in human beings ... a type of behaviour which counts as specifically human" (1925).[61]

The August 2008 issue of the American Journal of Primatology reported results of a year-long study of chimpanzees in Tanzania’s Mahale Mountains National Park, which produced evidence of chimpanzees becoming sick from viral infectious diseases they had likely contracted from humans. Molecular, microscopic and epidemiological investigations demonstrated the chimpanzees living at Mahale Mountains National Park have been suffering from a respiratory disease that is likely caused by a variant of a human paramyxovirus.[62]

Research and study of chimpanzees

As of November 2007, about 1,300 chimpanzees were housed in 10 U.S. laboratories (out of 3,000 great apes living in captivity there), either wild-caught, or acquired from circuses, animal trainers, or zoos.[63] Most of the labs either conduct or make the chimps available for invasive research,[64] defined as "inoculation with an infectious agent, surgery or biopsy conducted for the sake of research and not for the sake of the chimpanzee, and/or drug testing".[65] Two federally funded laboratories use chimps: the Yerkes National Primate Research Center at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, and the Southwest National Primate Center in San Antonio, Texas.[66] Five hundred chimps have been retired from laboratory use in the U.S. and live in animal sanctuaries in the U.S. or Canada.[64]

Chimpanzees used in biomedical research tend to be used repeatedly over decades, rather than used and killed as with most laboratory animals. Some individual chimps currently in U.S. laboratories have been used in experiments for over 40 years.[67] According to Project R&R, a campaign to release chimps held in U.S. labs—run by the New England Anti-Vivisection Society in conjunction with Jane Goodall and other primate researchers—the oldest known chimp in a U.S. lab is Wenka, which was born in a laboratory in Florida on May 21, 1954.[68] She was removed from her mother on the day of birth to be used in a vision experiment that lasted 17 months, then sold as a pet to a family in North Carolina. She was returned to the Yerkes National Primate Research Center in 1957 when she became too big to handle. Since then, she has given birth six times, and has been the subject of research into alcohol use, oral contraceptives, aging, and cognitive studies.[69]

With the publication of the chimpanzee genome, plans to increase the use of chimps in labs are reportedly increasing, with some scientists arguing that the federal moratorium on breeding chimps for research should be lifted.[66][70] A five-year moratorium was imposed by the U.S. National Institutes of Health in 1996, because too many chimps had been bred for HIV research, and it has been extended annually since 2001.[66]

Other researchers argue that chimps are unique animals and either should not be used in research, or should be treated differently. Pascal Gagneux, an evolutionary biologist and primate expert at the University of California, San Diego, argues, given chimpanzees' sense of self, tool use, and genetic similarity to human beings, studies using chimps should follow the ethical guidelines used for human subjects unable to give consent.[66] Also, a recent study suggests chimpanzees which are retired from labs exhibit a form of posttraumatic stress disorder.[71] Stuart Zola, director of the Yerkes National Primate Research Laboratory, disagrees. He told National Geographic: "I don't think we should make a distinction between our obligation to treat humanely any species, whether it's a rat or a monkey or a chimpanzee. No matter how much we may wish it, chimps are not human."[66]

An increasing number of governments are enacting a great ape research ban forbidding the use of chimpanzees and other great apes in research or toxicology testing.[72] As of 2006, Austria, New Zealand, the Netherlands, Sweden, and the UK had introduced such bans.[73]

Studies of language

Scientists have long been fascinated with the studies of language, believing it to be a unique human cognitive ability. To test this hypothesis, scientists have attempted to teach human language to several species of great apes. One early attempt by Allen and Beatrix Gardner in the 1960s involved spending 51 months teaching American Sign Language (ASL) to a chimpanzee named Washoe. The Gardners reported Washoe learned 151 signs, and she had spontaneously taught them to other chimpanzees.[74] Over a longer period of time, Washoe learned over 800 signs.[75]

Debate is ongoing among some scientists (such as David Premack), about non-human great apes' ability to learn language. Since the early reports on Washoe, numerous other studies have been conducted, with varying levels of success,[76] including one involving a chimpanzee named jokingly Nim Chimpsky, trained by Herbert Terrace of Columbia University. Although his initial reports were quite positive, in November 1979, Terrace and his team, including psycholinguist Thomas Bever, re-evaluated the videotapes of Nim with his trainers, analyzing them frame by frame for signs, as well as for exact context (what was happening both before and after Nim's signs). In the reanalysis, Terrace and Bever concluded Nim's utterances could be explained merely as prompting on the part of the experimenters, as well as mistakes in reporting the data. "Much of the apes' behaviour is pure drill," he said. "Language still stands as an important definition of the human species." In this reversal, Terrace now argued Nim's use of ASL was not like human language acquisition. Nim never initiated conversations himself, rarely introduced new words, and simply imitated what the humans did. More importantly, Nim's word strings varied in their ordering, suggesting that he was incapable of syntax. Nim's sentences also did not grow in length, unlike human children whose vocabulary and sentence length show a strong positive correlation.[77]

Memory

A 30-year study at Kyoto University's Primate Research Institute has shown that chimps are able to learn to recognise the numbers 1 through 9 and their values. The chimps further show an aptitude for photographic memory, demonstrated in experiments in which the jumbled digits are flashed onto a computer screen for less than a quarter of a second. One chimp, Ayumu, was able to correctly and quickly point to the positions where they appeared in ascending order. The same experiment was failed by human world memory champion Ben Pridmore on most attempts.[78]

Laughter in apes

Laughter might not be confined or unique to humans. The differences between chimpanzee and human laughter may be the result of adaptations that have evolved to enable human speech. Self-awareness of one's situation as seen in the mirror test, or the ability to identify with another's predicament (see mirror neurons), are prerequisites for laughter, so animals may be laughing for the same reasons that humans do.

Chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans show laughter-like vocalizations in response to physical contact, such as wrestling, play-chasing, or tickling. This is documented in wild and captive chimpanzees. Common chimpanzee laughter is not readily recognisable to humans as such, because it is generated by alternating inhalations and exhalations that sound more like breathing and panting. Instances in which nonhuman primates have expressed joy have been reported. One study analyzed and recorded sounds made by human babies and bonobos when tickled. Although the bonobo's laugh was a higher frequency, the laugh followed a pattern similar to that of human babies and included similar facial expressions. Humans and chimpanzees share similar ticklish areas of the body, such as the armpits and belly. The enjoyment of tickling in chimpanzees does not diminish with age.[79]

Chimps listed as endangered in the US

The US Fish and Wildlife Service finalized a rule on June 12, 2015, creating very strict regulations, practically barring any activity with chimpanzees other than for scientific, preservation-oriented purposes.[80]

Chimpanzees as pets

Chimpanzees have traditionally been kept as pets in a few African villages, especially in the Democratic Republic of Congo. In Virunga National Park in the east of the country, the park authorities regularly confiscate chimpanzees from people keeping them as pets.[81]

Chimpanzees are popular as wild pets in many areas despite their strength, aggression, and wild nature. Even in areas where keeping non-human primates as pets is illegal, the exotic pet trade continues to prosper and some people keep chimpanzees as pets mistakenly believing that they will bond with them for life. As they grow, so do their strength and aggression; some owners and others interacting with the animals have lost fingers and suffered severe facial damage among other injuries sustained in attacks. In addition to the animals' hostile potential and strength well beyond any human being, chimpanzees physically mature a lot more proportionally than do human beings, and even among the most cleanly and well-organized of housekeepers, maintaining cleanliness and control of chimpanzees is physically demanding to the point that it is impossible for humans to control, especially due to the animals' strength and aggression.[82]

Chimpanzees in popular culture

Chimpanzees have been commonly stereotyped in popular culture, where they are most often cast in standardized roles as childlike companions, sidekicks or clowns.[83] They are especially suited for the latter role on account of their prominent facial features, long limbs and fast movements, which humans often find amusing. Accordingly, entertainment acts featuring chimpanzees dressed up as humans have been traditional staples of circuses and stage shows.[83]

In the age of television, a new genre of chimp act emerged in the United States: series whose cast consisted entirely of chimpanzees dressed as humans and "speaking" lines dubbed by human actors.[83] These shows, examples of which include Lancelot Link, Secret Chimp in the 1970s or The Chimp Channel in the 1990s, relied on the novelty of their ape cast to make their timeworn, low comedy gags funny.[83] Their chimpanzee "actors" were as interchangeable as the apes in a circus act, being amusing as chimpanzees and not as individuals.[83] Animal rights groups have urged a stop to this practice, considering it animal abuse.[84]

When chimpanzees appear in other TV shows, they generally do so as comic relief sidekicks to humans. In that role, for instance, J. Fred Muggs appeared with Today Show host Dave Garroway in the 1950s, Judy on Daktari in the 1960s and Darwin on The Wild Thornberrys in the 1990s.[83] In contrast to the fictional depictions of other animals, such as dogs (as in Lassie), dolphins (Flipper), horses (The Black Stallion) or even other great apes (King Kong), chimpanzee characters and actions are rarely relevant to the plot.[83]

Chimpanzees in science fiction

The rare depictions of chimpanzees as individuals rather than stock characters, and as central rather than incidental to the plot[83] are generally found in works of science fiction. Robert A. Heinlein's short story "Jerry Was a Man" (1947) centers on a genetically enhanced chimpanzee suing for better treatment. The 1972 film Conquest of the Planet of the Apes, the third sequel of Planet of the Apes, portrays a futuristic revolt of enslaved apes led by the only talking chimpanzee, Caesar, against their human masters.[83]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Groves, C.P. (2005). Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M., eds. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 182–3. OCLC 62265494. ISBN 0-801-88221-4.

- ↑ Shefferly, N. (2005). "Pan troglodytes". Animal Diversity Web (University of Michigan Museum of Zoology). Retrieved 2007-08-11.

- ↑ The London Magazine 465, September 1738. "A most surprising creature is brought over in the Speaker, just arrived from Carolina, that was taken in a wood at Guinea. She is the Female of the Creature which the Angolans call chimpanze, or the mockman." (cited after OED)

- ↑ "chimpanzee" in American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fifth Edition, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2011.

- ↑ "Chimpanzee, the name of an Angolan animal [...] In the year 1738, we had one of these creatures brought over into England." (cited after OED)

- ↑ "Online Etymology Dictionary". Retrieved 2015-03-12. "chimp definition | Dictionary.com". Dictionary.reference.com. Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- ↑ p. 37 in Blumenbach, J. F. 1776. De generis hvmani varietate nativa liber. Cvm figvris aeri incisis. – pp. [1], 1–100, [1], Tab. I-II [= 1–2]. Goettingae. (Vandenhoeck).

- ↑ AnimalBase species taxon summary for troglodytes Blumenbach, 1776 described in Simia, version 11 June 2011

- 1 2 Tubbs, P.K. 1985: OPINION 1368. THE GENERIC NAMES PAN AND PANTHERA (MAMMALIA, CARNIVORA): AVAILABLE AS FROM OKEN, 1816. Bulletin of zoological nomenclature, 42: 365-370. ISSN 0007-5167 Internet Archive BHL BioStor corrigendum in Bulletin of zoological nomenclature, 45: 304. (1988) Internet Archive http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/44486#4 BHL

- ↑ Bo Beolens, Michael Watkins, Michael Grayson, The Eponym Dictionary of Mammals, JHU Press, 2009.

- ↑ Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary: "A little Pan, a rural deity"

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard (2004). "Chimpanzees". The Ancestor's Tale. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 1-155-16265-X.

- ↑ Wakeley J (March 2008). "Complex speciation of humans and chimpanzees". Nature 452 (7184): E3–4; discussion E4. doi:10.1038/nature06805. PMID 18337768.

- ↑ What is the latest theory of why humans lost their body hair? Why are we the only hairless primate?, Scientific American

- ↑ Mary-Claire King (1973) Protein polymorphisms in chimpanzee and human evolution, Doctoral dissertation, University of California, Berkeley.

- ↑ Minkel JR (2006-12-19). "Humans and Chimps: Close But Not That Close". Scientific American.

- ↑ Wong, Kate (1 September 2014). "Tiny Genetic Differences between Humans and Other Primates Pervade the Genome". Scientific American.

- ↑ Gibbons, Ann (13 June 2012). "Bonobos Join Chimps as Closest Human Relatives". Science/AAAS.

- ↑ Israfil, H.; Zehr, S. M.; Mootnick, A. R.; Ruvolo, M.; Steiper, M. E. (2011). "Unresolved molecular phylogenies of gibbons and siamangs (Family: Hylobatidae) based on mitochondrial, Y-linked, and X-linked loci indicate a rapid Miocene radiation or sudden vicariance event" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 58 (3): 447–455. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2010.11.005. PMC 3046308

. PMID 21074627.

. PMID 21074627. - ↑ McBrearty, S.; N. G. Jablonski (2005-09-01). "First fossil chimpanzee". Nature. 437 (7055): 105–8. Bibcode:2005Natur.437..105M. doi:10.1038/nature04008. PMID 16136135.

- ↑ Huxley, T. H. (1904). Science and education: Essays. JA Hill and company.

- ↑ "Chimpanzee", Rolling Hills Wildlife Adventure 2005

- ↑ "Gene study shows three distinct groups of chimpanzees". EurekAlert. 2007-04-20. Retrieved 2007-04-23.

- ↑ Tobias, P. (1971). The Brain in Hominid Evolution. New York, Columbia University Press, hdl:2246/6020; cited in Schoenemann PT. 1997. An MRI study of the relationship between human neuroanatomy and behavioral ability. PhD diss. Univ. of Calif., Berkeley

- ↑ Schoenemann, P. Thomas (2006). "Evolution of the Size and Functional Areas of the Human Brain". Annual Review of Anthropology. 35 (1): 379–406. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.35.081705.123210. "Modern human brain sizes vary widely, but average ∼1330 cc (Dekaban 1978, Garby et al. 1993, Ho et al. 1980a, Pakkenberg & Voigt 1964)" these references are listed on this page.

- ↑ "Why are rat testicles so big?". ratbehavior.org. 2003–2004. Retrieved 1 September 2009.

- ↑ "Advanced Age Influences Chimpanzee Behavior in Small Social Groups", Behavior of Aged Chimpanzees

- ↑ "The Strength of the Chimpanzee and Orang". JSTOR 6455.

- ↑ "Observations on the Strength of the Chimpanzee and Its Implications". JSTOR 1373587.

- ↑ "The Bodily Strength of Chimpanzees". JSTOR 1374806.

- ↑ Laird, Courtney (Spring 2004). "Social Organization". Davidson College. Archived from the original on February 9, 2007. Retrieved 2008-03-10.

- ↑ "Chimp Behavior". Jane Goodall Institute. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

- ↑ de Waal, F. (2006). "Apes in the family". Our Inner Ape. New York: Riverhead Books. ISBN 1-59448-196-2.

- ↑ Holland, Jennifer S. (2011). "40 Winks?". National Geographic. 220 (1).

- ↑ , LiveScience, April 11, 2007

- ↑ "Chimpanzee intelligence". Indiana University. 2000-02-23. Retrieved 2008-03-24.

- ↑ Osvath, Mathias (2009-03-10). "Spontaneous planning for future stone throwing by a male chimpanzee". Curr. Biol. 19 (5): R190–1. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.01.010. PMID 19278627.

- ↑ Mercader J., Barton H., Gillespie J. et al. (2007). "4,300-year-old chimpanzee sites and the origins of percussive stone technology". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 (9): 3043–8. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.3043M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0607909104. PMC 1805589

. PMID 17360606.

. PMID 17360606. - ↑ Bijal T. (2004-09-06). "Chimps Shown Using Not Just a Tool but a "Tool Kit"". Retrieved 2010-01-20.

- ↑ Carvalho Susana; et al. (2008). "Chaînes Opératoires and resource-exploitation strategies in chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) nut cracking". Journal of Human Evolution. 55 (1): 148–163. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.02.005.

- ↑ van Lawick-Goodall, Jane. 1970. "Tool-using in Primates and other Vertebrates." Advances in the Study of Behavior, vol. 3, edited by David S. Lehrman, Robert A. Hinde, and Evelyn Shaw. New York: Academic Press.

- ↑ Fox, M. (2007-02-22). "Hunting chimps may change view of human evolution". Archived from the original on 2007-02-24. Retrieved 2007-02-22.

- ↑ "ISU anthropologist's study is first to report chimps hunting with tools". Iowa State University News Service. 2007-02-22. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

- ↑ Whipps, Heather (2007-02-12). "Chimps Learned Tool Use Long Ago Without Human Help". LiveScience. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

- ↑ "Tool Use". Jane Goodall Institute. Archived from the original on 2007-05-20. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

- ↑ Wrangham, Richard W. (1996). Chimpanzee cultures. Chicago Academy of Sciences, Harvard University Press. pp. 115–125. ISBN 978-0-674-11663-4.

- ↑ Samson DR, Hunt KD (2014). "Chimpanzees Preferentially Select Sleeping Platform Construction Tree Species with Biomechanical Properties that Yield Stable, Firm, but Compliant Nests". PLoS ONE. 9 (4): e95361. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0095361. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- ↑ "Human-like Altruism Shown In Chimpanzees". Science Daily. 2007-06-25. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

- ↑ Bradley, Brenda (June 1999). "Levels of Selection, Altruism, and Primate Behavior". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 74 (2): 171–194. doi:10.1086/393070. PMID 10412224.

- ↑ Boesch, C., Bolé, C.; Eckhardt, N.; Boesch, H. (2010). Santos, Laurie, ed. "Altruism in Forest Chimpanzees: The Case of Adoption". PLoS ONE. 5 (1): e8901. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0008901.

- ↑ Harrod, James (May 10, 2007). "Appendices for Chimpanzee Spirituality: A Concise Synthesis of the Literature" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 27, 2008. Retrieved 2011-01-28.

- ↑ Chimpanzee Talking. YouTube. 17 August 2007. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ "Communication". Evolve. Season 1. Episode 7. 2008-09-14.

- ↑ Walsh, Bryan (2009-02-18). "Why the Stamford Chimp Attacked". TIME. Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- ↑ Teelen S (2008). "Influence of chimpanzee predation on the red colobus population at Ngogo, Kibale National Park, Uganda". Primates. 49 (1): 41–9. doi:10.1007/s10329-007-0062-1. PMID 17906844.

- ↑ Gibbons A (2007). "Primate behavior. Spear-wielding chimps seen hunting bush babies". Science. 315 (5815): 1063. doi:10.1126/science.315.5815.1063. PMID 17322034.

- ↑ Pruetz JD, Bertolani P (2007). "Savanna chimpanzees, Pan troglodytes verus, hunt with tools". Curr. Biol. 17 (5): 412–7. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2006.12.042. PMID 17320393.

- ↑ Richard Gray (24 February 2013). "Chimps solve puzzles for the thrill of it, researchers find". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ↑ Goodall, Jane (1986). The Chimpanzees of Gombe: Patterns of Behavior. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-11649-6.

- ↑ Newswise: Researchers Find Human Virus in Chimpanzees Retrieved on June 5, 2008.

- ↑ "End chimpanzee research: overview". Project R&R, New England Anti-Vivisection Society. 2005-12-11. Retrieved 2008-03-24.

- 1 2 "Chimpanzee lab and sanctuary map". The Humane Society of the United States. Archived from the original on March 7, 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-24.

- ↑ "Chimpanzee Research: Overview of Research Uses and Costs". Humane Society of the United States. Archived from the original on 2008-03-07. Retrieved 2008-03-24.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lovgren, Stefan. Should Labs Treat Chimps More Like Humans?, National Geographic News, September 6, 2005.

- ↑ Chimps Deserve Better, Humane Society of the United States.

- ↑ A former Yerkes lab worker. "Release & Restitution for Chimpanzees in U.S. Laboratories " Wenka". Releasechimps.org. Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- ↑ Wenka, Project R&R, New England Anti-Vivisection Society.

- ↑ Langley, Gill (June 2006). Next of Kin: A Report on the Use of Primates in Experiments, British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection, p. 15, citing VandeBerg JL, Zola SM (September 2005). "A unique biomedical resource at risk". Nature. 437 (7055): 30–2. Bibcode:2005Natur.437...30V. doi:10.1038/437030a. PMID 16136112.

- ↑ Bradshaw GA, Capaldo T, Lindner L, Grow G (2008). "Building an inner sanctuary: complex PTSD in chimpanzees" (PDF). J Trauma Dissociation. 9 (1): 9–34. doi:10.1080/15299730802073619. PMID 19042307.

- ↑ Guldberg, Helen. The great ape debate, Spiked online, March 29, 2001. Retrieved August 12, 2007.

- ↑ Langley, Gill (June 2006). Next of Kin: A Report on the Use of Primates in Experiments, British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection, p. 12.

- ↑ Gardner, R. A.; Gardner, B. T. (1969). "Teaching Sign Language to a Chimpanzee". Science. 165 (3894): 664–672. Bibcode:1969Sci...165..664G. doi:10.1126/science.165.3894.664. PMID 5793972.

- ↑ Allen, G. R.; Gardner, B. T. (1980). "Comparative psychology and language acquisition". In Thomas A. Sebok and Jean-Umiker-Sebok. Speaking of Apes: A Critical Anthology of Two-Way Communication with Man. New York: Plenum Press. pp. 287–329. ISBN 0306402793.

- ↑ "Language of Bonobos". Great Ape Trust. Archived from the original on 2004-08-15. Retrieved 2012-01-16.

- ↑ Wynne, Clive (October 31, 2007). "eSkeptic". Skeptic. Retrieved 2011-01-28.

- ↑ The study was presented in a Channel 5 (UK) documentary "The Memory Chimp", part of the channel's Extraordinary Animals series.

- ↑ Johnson, Steven (2003-04-01). "Emotions and the Brain". Discover Magazine. Retrieved 2007-12-10.

- ↑ "U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Finalizes Rule Listing All Chimpanzees as Endangered Under the Endangered Species Act". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 2016-08-30.

Certain activities involving chimpanzees will be prohibited without a permit, including import and export of the animals into and out of the United States, "take" (defined by the ESA as harm, harass, kill, injure, etc.) within the United States, and interstate and foreign commerce. Permits will be issued for these activities only for scientific purposes that benefit the species in the wild, or to enhance the propagation or survival of chimpanzees, including habitat restoration and research on chimpanzees in the wild that contributes to improved management and recovery.

- ↑ "Gorilla diary: August – December 2008". BBC News. 2009-01-20. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ "Chimpanzees Don't Make Good Pets". The Jane Goodall Institute. Archived from the original on 2 February 2015. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Van Riper, A. Bowdoin (2002). Science in popular culture: a reference guide. Westport: Greenwood Press. pp. 18–19. ISBN 0-313-31822-0.

- ↑ "Animal Actors | PETA.org". Nomoremonkeybusiness.com. Retrieved 2011-01-28.

References

- Pickrell, John. (September 24, 2002). "Humans, Chimps Not as Closely Related as Thought?". National Geographic.

Further reading

- Hawks, John. "How Strong Is a Chimpanzee?" Slate, February 25, 2009.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Chimpanzee |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Chimpanzee |

-

Media related to Pan at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pan at Wikimedia Commons -

Ingersoll, Ernest (1920). "Chimpanzee". Encyclopedia Americana.

Ingersoll, Ernest (1920). "Chimpanzee". Encyclopedia Americana. -

Lydekker, Richard (1911). "Chimpanzee". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.).

Lydekker, Richard (1911). "Chimpanzee". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). - Stanford, Craig B. The Predatory Behavior and Ecology of Wild Chimpanzees university of Southern California. 2002(?)

- ChimpCARE.org

- View the panTro4 genome assembly in the UCSC Genome Browser.

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).