Chichewa tones

Chichewa (a Bantu language of Central Africa, also known as Chewa, Nyanja, or Chinyanja) is the main language spoken in south and central Malawi, and to a lesser extent in Zambia, Mozambique and Zimbabwe. Like most other Bantu languages, it is tonal; that is to say, pitch patterns are an important part of the pronunciation of words. Thus, for example, the word chímanga (high-low-low) "maize" can easily be distinguished from chinangwá (low-low-high) "cassava" not only by its consonants but also by its pitch pattern.

Tones (the rises and falls in pitch of the voice) also play an important grammatical role in Chichewa verbs, distinguishing one tense from another or different nuances of meaning within the same tense.

Thirdly, tones play a part in intonation and phrasing. One intonational tone often encountered is a mid-sentence boundary tone, which is a rise in pitch heard on the last syllable before a pause in the middle of the sentence; another is a rising or falling tone heard at the end of some types of questions.

Chichewa tones have been the subject of much scholarly interest in the last few years, mainly for the light they throw on different theories of phonology and phonetics.

Introduction

Certain syllables in Chichewa words, for example the first syllable of nsómba 'fish', are associated with a high pitch. These syllables are said to have a 'high tone'. A high tone remains high in whatever context the word is used; in this respect high-toned syllables differ from accented syllables in English.

In terms of pitch the word nsómba sounds not very different from the English word longer, when pronounced in isolation. The difference between Chichewa and English is that when an English word like longer is used in a sentence, it can change its pitch-pattern: sometimes the first syllable may be lower than the second, or at other times both syllables may be low.[1] In a tonal language, on the other hand, a high tone remains high wherever the word is used in a sentence, although the height may vary from one part of the sentence to another.

Not every word in Chichewa has a high tone. Some words, such as Lilongwe (the capital of Malawi), are toneless and are pronounced with all the syllables on a low pitch (like the word station in the English police-station). Most words have one high tone (usually on one of the last three syllables of the word),[2] and a few, especially verbal forms such as ndímapíta 'I go', have two high tones. Some have three high tones in a row, as in chákúdyá 'food'.

Pronunciation of tones

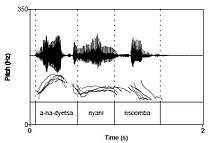

The accompanying illustration[3] shows how the speaker's voice glides up and down when the tones are pronounced in a sentence. A notable feature of Chichewa is that in a declarative sentence, the height of the tones usually gets smaller as the sentence proceeds. This phenomenon is known as downdrift. However, downdrift only occurs when there is one or more toneless syllables between the high tones (HLH). When two tones come in succession, as in the words nyaní nsómba, there is usually no fall in pitch from one to another.

When a word has a high tone on the final syllable, as in nyaní 'baboon' in the illustration, the tone usually spreads backwards to cover part or all of the previous syllable as well. A word-final tone is also not as high in pitch as a tone on the penultimate syllable of a word. Often the part of the tone on the penultimate syllable rises slightly, especially when the word begins a sentence.[4]

When a word with word-final tone comes at the end of a sentence or is spoken in isolation, the speaker's voice may either continue without dropping, or it may drop on final syllable, leaving just a slightly rising tone on the penultimate. Some authors[5] write this with the symbol for a rising tone: nyăni.

In some dialects a word-final tone can be pronounced without backwards spreading if it is connected to the following word to make a phrase, e.g. nyaní wafa 'the baboon has died'.[6]

Number of tones

Two pitch levels, high and low, conventionally written H and L, are usually considered to be sufficient to describe the tones of Chichewa.[7] In Chichewa itself the high tone is called mngóli wókwéza ('tone of raising'), and the low tone mngóli wótsítsa ('tone of lowering').[8] Some authors[9] add a mid-height tone but most do not, but consider a mid-height tone to be merely a reflection of nearby high tones.

From a theoretical point of view, however, it has been argued that Chichewa tones are best thought of not in terms of H and L, but in terms of H and Ø, that is to say, high-toned vs toneless syllables.[10] The reason is that H tones are much more dynamic than L tones and play a large role in tonal phenomena, whereas L-toned syllables are relatively inert.[11] Some authors therefore, instead of referring to ‘high’ and ‘low’ tones, prefer to write in terms of syllables which have a 'high tone' (or simply a ‘tone’) vs those which are 'toneless'.[12]

In most words other than compounds and verbs there is usually just one high tone or none; if there is a single high tone, it is usually heard in one of the last three syllables of the word.[13] This relatively simple type of tonal system has sometimes been referred to in the past as a pitch-accent system;[14] but with increasing knowledge of the variety of the tonal systems of different languages, it has been argued that this term is an over-simplification and should be avoided.[15] Nowadays therefore languages of all types with tones are usually referred to as tonal languages.

Tones are not marked in the standard orthography used in Chichewa books and newspapers, but linguists usually indicate a high tone by writing it with an acute accent, as in the first syllable of nsómba. The low tones are generally left unmarked.

Works describing Chichewa tones

The earliest work to mark the tones of Chichewa words was the Afro-American scholar Mark Hanna Watkins’ A Grammar of Chichewa (1937). This was a pioneering work, since not only was it the first work on Chichewa to include tones, but it was also the first grammar of any African language to be written by an American.[16] The informant used by Watkins was the young Kamuzu Banda, who in 1966 was to become the first President of the Republic of Malawi.

Another grammar including Chichewa tones was a handbook written for Peace Corps Volunteers, Stevick et al., Chinyanja Basic Course (1965), which gives very detailed information on the tones of sentences, and also indicates intonations.[17] Its successor, Scotton and Orr (1980) Learning Chichewa,[18] is much less detailed. All three of these works are available on the Internet. J.K. Louw's Chichewa: A Practical Course (1980), which contained tone markings, is no longer available.

From 1976 onwards a number of academic articles by Malawian and Western scholars have been published on different aspects of Chichewa tones.

Three dictionaries also mark the tones on Chichewa words: these are A Learner's Chichewa-English, English-Chichewa Dictionary by Botne and Kulemeka (1991), the monolingual Mtanthauziramawu wa Chinyanja/Chichewa (c.2000) produced by the Centre for Language Studies of the University of Malawi (available online),[19] and the Common Bantu On-Line Chichewa Dictionary (2001) formerly published online by the University of California in Berkeley.[20]

So far all the studies which have been published on Chichewa tones have dealt with the Malawian variety of the language. There is no published information available on the tones of Chinyanja spoken in Zambia and Mozambique.

Some tonal phenomena

In order to understand Chichewa tones, it is necessary first to understand various tonal phenomena that can occur, which are briefly outlined below.

Downdrift

Normally in a Chichewa sentence, whenever tones come in the sequence HLH or HLLH, it is usual for the second high tone to be a little lower than the first one. So for example in the word ndímapíta ‘I usually go’, the tone of ndí is pronounced a little higher than the tone of pí. Thus generally speaking the highest tone in a sentence is the first one. This phenomenon, which is common in many Bantu languages, is known as 'downdrift'[21] or 'automatic downstep'.[22]

However, there are several exceptions to this rule. Downdrift does not occur, for example, when a speaker is asking a question,[23] or reciting a list of items with a pause after each one, or sometimes if a word is pronounced on a high pitch for emphasis. There is also no downdrift in words like wápolísi 'policeman', where two high tones in the sequence HLH are bridged to make a plateau HHH (see below).

High tone spreading (‘HTS’)

In some dialects a high tone may sometimes spread to the following syllable. So where some speakers say ndináthandiza ‘I helped’, others will say ndináthándiza.[24] Some phoneticians argue that what happens here, in some cases at least, is that the highest part or 'peak' of the tone moves forward, giving the impression that the tone covers two syllables, a process called ‘peak delay’.[25] An illustration of peak delay can be seen clearly in the pitch-track of the word anádyetsa ‘they fed’, here pronounced anádyétsa, in Downing et al. (2004).

In order for HTS to occur, there must be at least 3 syllables following the tone, although not necessarily in the same word.

One very frequent use of spreading, at least in some dialects, is to link together two words (such as verb + object, or verb of motion + destination, or noun + possessive) into a single phrase. In transcriptions one frequently finds phrases such as kuphíká nyama ‘to cook meat’[26] or kusámála mkázi ‘to care for a wife’,[27] chímánga chánga ‘my maize’[28] mikángó iyo ‘those lions’[29] etc. in which the second tone in each phrase is not original but due to spreading. It should be noted, however, that the contexts where spreading occurs vary from one dialect to another.

Tonal plateau

It sometimes happens that the sequence HLH in Chichewa becomes HHH, making a tonal 'plateau'. A tonal plateau is common after the words á 'of' and ndí 'and':

- wápolísi 'policeman' (from wá 'of' and polísi 'police')

- chákudyá 'food' (from chá 'of' and kudyá 'to eat')

- ndí Maláwi 'and Malawi'

Before a pause the final tone may drop: chákúdya. Sometimes a succession of tones is bridged in this way, e.g. gúlewámkúlu with one long continuous high tone from gú to kú.[30]

Another place where a plateau is found is after the initial high tone of subordinate clause verbs such as the following:

- ákuthándiza 'when he is helping'; 'who is helping'

- ndítathándiza 'after I helped'

At the end of words, if the tones are HLH, a plateau is common:

- mpóngozí 'mother-in-law'

- kusíyaná 'difference'

- ankápitá 'he used to go'

However, there are exceptions; for example, in some tenses such as the Present Habitual and in the Negative Past, monosyllabic verbs do not make a plateau, but are pronounced with two separate tones with downstep:

- ndímadyá 'I eat'

- sánadyé 'he didn't eat'

The high tones in the word nyényezí 'star' are also kept separate.

Sequences with two or more toneless syllables between the high tones (e.g. HLLH) do not normally make a plateau in Chichewa.

Tone shifting ('bumping')

When a word or closely connected phrase ends in HHL or HLHL, there is a tendency in Chichewa for the second H to move to the final syllable of the word. This process is known as ‘tone shifting’[31] or ‘bumping’.[32]

Local bumping

In one type of bumping (called ‘local bumping’) LHHL at the end of a word or phrase becomes LHHH (where the two tones are joined into a plateau):

- *nyumbá yánga > nyumbá yángá 'my house'

- *kupítá-nso > kupítá-nsó 'to go again'

- *ndinkápíta > ndinkápítá 'I used to go'

- *anámúpha > anámúphá 'they killed him'

At the end of a sentence the final high tone may drop again, reverting the word to anámúpha.

However, in certain verb tenses such as the Present Habitual when the tones are HHL, the penultimate tone is shifted to the final, but there is no plateau. Instead, the two tones are kept separate:

- ndímadyá 'I eat'

There is no bumping in HHL words where the first syllable is derived from á 'of':

- kwámbíri 'very much'

Non-local bumping

In another kind (called ‘non-local bumping’), HLHL at the end of a word or phrase changes to HLLH or, with spreading of the first high tone, HHLH:

- *mbúzi yánga > mbúzi yangá (or mbúzí yangá) 'my goat'

- *bánja lónse > bánja lonsé 'the whole family'

- *chimódzimódzi > chimódzimodzí 'in the same way'

Again, the Present Habitual is an exception, and when the tones are HLHL, bumping does not occur:

- ndímapíta 'I go'

Reverse bumping

A related phenomenon, but in reverse, is found when the addition of the suffix -tú 'really' causes a normally word-final tone to move back one syllable, so that LHH at the end of a word becomes HLH:

- *ndipité 'I should go' > ndipíte-tú 'really I should go'

- *chifukwá 'because' > chifúkwa-tú 'because in fact'

Enclitic suffixes

Certain suffixes, known as enclitics, add a high tone to the last syllable of the word to which they are joined. When added to a toneless word or a word ending in LL, this high tone can easily be heard. Bumping does not occur when the tones are HLHL:

- Lilongwe > Lilongwé-nso ‘Lilongwe also’

- akuthándiza > akuthándizá-be ‘he's still helping’

But when an enclitic is combined with word which has penultimate high tone, there is local bumping, and the result is a triple tone:

- nsómba > nsómbá-nsó ‘the fish also’

When added to a word with final high tone, it raises the tone higher (in Central Region dialects, the rising tone on the first syllable of a word like nyŭmbá also disappears):[33]

- nyumbá > nyumbá-nso ‘the house also’

Not all suffixes are tonally enclitic in this way. For example, when added to nouns, locative suffixes (-ko, -po, -mo) do not add a tone, e.g.:

- ku Lilongwe-ko ‘there in Lilongwe’

However, when added to verbs, the same suffixes add an enclitic tone:

- wachoká-po ‘he's not at home’ (lit. ‘he has gone away from there’)

Proclitic prefixes

Conversely, certain verb-prefixes transfer their high tone to the syllable which follows them. Prefixes of this kind are called 'proclitic'.[34] The infinitive is typical of this group:

- Infinitive: ku-thándiza 'to help' (but the negative has penultimate tone: ku-sa-thandíza 'not to help')

Other tenses of this kind are:

- Present Continuous: ndi-ku-thándiza 'I am helping'

- Recent Past Continuous: ndi-ma-thándiza 'I was helping'

- Recent Past Simple: ndi-na-thándiza 'I helped just now'

- Immediate Imperative: ta-thándiza! 'help (now)!'[35]

- Verbal Adjective (derived from á 'of' + the Infinitive): wó-thándiza 'who helps'

A frequent situation in Chichewa is when one of these verb-prefixes is added to a verb which has a high-toned prefix such an object-marker (e.g. -mú- 'him') or the directional aspect-marker (-ká- 'go and'). In this case, an extra tone will appear on the penultimate syllable, which in shorter verbs will be bumped to the final:[36]

- ku-mú-fotokozéra 'to explain to him'

- ku-mú-vundikíra 'to cover him'

- ku-mú-thandizá 'to help him'

- ku-mú-ményá 'to hit him'

With a monosyllabic verb, the second tone disappears by Meeussen's rule (see below):

- ku-mú-pha 'to kill him'

Meeussen's Rule

Meeussen’s Rule is a process in several Bantu languages whereby a sequence HH becomes HL. This is frequent in verbs. An example in Chichewa is the infinitive kú- + goná ‘to sleep’, where the addition of the proclitic kú- would normally be expected to produce ku-góná with two high tones; but by Meeussen’s Rule the second tone is dropped, leaving ku-góna with a high tone on the penultimate only. In the Southern Region, a-ná-mú-thandiza ‘he helped him’ is pronounced a-ná-mu-thandiza, presumably also by Meeussen’s Rule.[37]

Meeussen’s Rule does not apply in every circumstance. For example, a tone derived from spreading is unaffected by it, e.g. ku-góná bwino ‘to sleep well’, where the second tone, having been deleted by Meeussen’s Rule, is replaced by spreading.[38]

Tone of consonants

Just as in English, where in a word like zoo or wood or now the initial voiced consonant has a low pitch compared with the following vowel, the same is true of Chichewa. Thus Trithart marks the tones of initial consonants such as [m], [n], [z], and [dz] in some words as Low.[39]

However, an initial nasal consonant is not always pronounced with a low pitch. After a high tone it can acquire a high tone itself, e.g. wá ḿsodzi ‘of the fisherman’[40] The consonants n and m can also have a high tone when contracted from ndí ‘and’ or high-toned -mú-, e.g. ḿmakhálá kuti? ‘where do you live?’.[41]

In some Southern African Bantu languages such as Zulu a voiced consonant at the beginning of a syllable not only has a low pitch itself, but can also lower the pitch of all or part of the following vowel. Such consonants are known as ‘depressor consonants’. The question of whether Chichewa has depressor consonants was first considered by Trithart (1976) and further by Cibelli (2012). According to data collected by Cibelli, a voiced or nasalised consonant does indeed have a small effect on the tone of a following vowel, making it a semitone or more lower; so that for example the second vowel of ku-gúla ‘to buy’ would have a slightly lower pitch than that of ku-kúla ‘to grow’ or ku-khála ‘to sit’. When the vowel is toneless, the effect is less, but it seems that there is still a slight difference. The effect of depressor consonants in Chichewa, however, is much less noticeable than in Zulu.

Lexical tones

Lexical tones are the tones of individual words - or the lack of tones, since quite a large number of words in Chichewa (including over a third of nouns and most verbs in their basic form) are toneless and pronounced with all their syllables on a low pitch.

Nouns

In the CBOLD Chichewa dictionary,[42] about 36% of Chichewa nouns are toneless, 57% have one tone, and only 7% have more than one tone. When there is one tone, it is generally on one of the last three syllables. Nouns with a tone more than three syllables from the end are virtually all foreign borrowings, such as sékondale ‘secondary school’.

Comparison with other Bantu languages shows that for the most part the tones of nouns in Chichewa correspond to the tones of their cognates in other Bantu languages, and are therefore likely to be inherited from an earlier stage of Bantu.[43] An exception is that nouns which at an earlier period had HH (such as nsómba ‘fish’, from proto-Bantu *cómbá) have changed in Chichewa to HL by Meeussen's rule. Two-syllable nouns in Chichewa can therefore have the tones HL, LH, or LL, these three being about equally common, but (discounting the fact that LH words are usually in practice pronounced HH) there are no nouns with the underlying tones HH.

The class-prefix of nouns, such as (class 7) chi- in chikóndi ‘love’, or (class 3) m- in mténgo ‘tree’, is usually toneless. However, there are some exceptions such as chímanga ‘maize’. The three nouns díso ‘eye’, dzíno ‘tooth’, and líwu ‘sound or word’ are irregular in that the high tone moves from the prefix to the stem in the plural, making masó, manó, and mawú respectively.[44]

Toneless nouns

- chinthu ‘thing’

- chipatala ‘hospital’

- dzanja ‘hand’

- Lilongwe ‘Lilongwe’

- magazi ‘blood’

- magetsi ‘electricity’

- mayeso ‘exam’

- mkaka ‘milk’

- mlimi ‘farmer’

- mowa ‘beer’

- moyo ‘life’

- mpando ‘chair’

- mpira ‘ball’

- msewu ‘road’

- msonkhano ‘meeting’

- mudzi ‘village’

- munthu ‘person’

- mzinda ‘city’

- ng’ombe ‘cow, ox’

- njala ‘hunger’

- njira ‘path’

- nyama ‘animal, meat’

Nouns with final tone

- bwaló ‘open area’

- chaká ‘year’

- Chichewá ‘Chichewa’

- galú ‘dog’

- madzí ‘water’

- maló ‘place’

- masó ‘eyes’

- mawú ‘word’

- mnyamatá ‘boy’

- mundá ‘garden’

- mutú ‘head’

- mwalá ‘stone’

- mwaná ‘child’

- njingá ‘bicycle’

- nyanjá ‘lake’

- nyumbá ‘house’

- nzerú ‘wisdom’

- ufulú ‘freedom’

- ulendó ‘journey’

- Zombá ‘Zomba’

Nouns with penultimate tone

- Bánda ‘Banda’

- bánja ‘family’

- bóma ‘government’

- búngwe ‘organisation’

- chikóndi ‘love’

- chitsánzo ‘example’

- dzíko ‘country’

- gúle ‘dance’

- Maláwi ‘Malawi’

- mankhwála ‘medicine’

- máyi ‘mother, woman’

- mbáli ‘side’

- mbéwu ‘seed, crop’

- mfúmu ‘chief’

- mkángo ‘lion’

- mpíngo ‘church, congregation’

- mténgo ‘tree’

- mtíma ‘heart’

- mvúla ‘rain’

- mwamúna ‘man’

- ndaláma ‘money’

- nkháni ‘story’

- nsómba ‘fish’

- ntchíto ‘work’

- ntháwi ‘time’

- nyímbo ‘song’

- tsíku ‘day’

- vúto ‘problem’

Nouns with antepenultimate tone

- búluzi ‘lizard’

- chímanga ‘maize’

- khwángwala ‘crow’

- maséwero ‘sport’

- mbálame ‘bird’

- mphépete ‘side, edge’

- mpóngozi ‘mother-in-law’

- msúngwana ‘teenage girl’

- mtsíkana ‘girl’

- námwali ‘initiate’

- njénjete ‘house-cricket’

- síng’anga ‘witch-doctor’

This group is less common than the first three. Many of the words with this tone are loanwords from Portuguese or English such as:

- bótolo ‘bottle’

- kálata ‘letter’

- mákina ‘machine’

- mbátata ‘sweet potatoes’

- nsápato ‘shoe’

- pépala ‘paper’

Nouns with two tones

A small number of words (mostly compounds) have more than one tone. Some are compounded with á ‘of’, which has a high tone, so that wá + ntchíto ‘man of work’ becomes wántchíto ‘worker’ with two tones. In words with the sequence HLH like wá-polísi ‘policeman’ the high tones bridge to make HHH.

- chákúdyá ‘food’

- Láchíwíri ‘Tuesday’

- Lólémba ‘Monday’

- Lówéruka ‘Saturday’

- wákúbá ‘thief’

- wántchíto ‘worker’

- wápólísi ‘policeman’

- wódwála ‘sick person’

- wóphúnzira ‘pupil’

- zófúnda ‘bedclothes’

- zóóna ‘truth’

The prefix chi- in some words adds two high tones, of which the second is bumped to the final, making LHLLH (or LHHLH) or LHHH:

- chikwángwání ‘banner, sign’

- chilákolakó ‘desire’

- chipólówé ‘violence, riot’

- chipwírikití ‘riot’

- chithúnzithunzí ‘picture’

- chitsékereró ‘stopper’

- chivúndikiró ‘lid’

- chiwóngoleró ‘steering-wheel’

- chizólowezí (or chizólówezí) ‘habit, custom’

The (L)HHH pattern is also found in a few other words:

- kusíyáná ‘difference’

- masómphényá ‘vision’

- mkámwíní ‘son-in-law’

- tsábólá ‘pepper’

Less common patterns are found in:

- bírímánkhwe ‘chameleon’

- gálímoto ‘car’

- kángachépe ‘small bribe, tip’

- nyényezí (also nyényezi) ‘star’

Adjectives

Adjectives in Chichewa are usually formed with word á (wá, yá, chá, zá etc. according to noun class) ‘of’, which has a high tone. The high tone tends to spread to the following word. When there is a sequence of HLH, the tones will bridge to make HHH:

- wá-bwino ‘good’[45]

- wá-ḿkázi ‘female’

Combined with an infinitive, á and ku- usually merge (except usually in monosyllabic verbs) into ó-:

- wó-ípa ‘bad’

- wó-pénga ‘mad’

- wó-dwála ‘sick’[46]

- wá-kú-yá ‘deep’

Some people hear a slight dip between the two tones:

- wô-dúla ‘expensive’[47]

Possessive adjectives are also made with á-. As explained in the section on bumping, their tone may change when they follow a noun ending in HL, LH or HH. The concords shown below are for noun classes 1 and 2:

- wánga 'my'

- wáko 'your'

- wáke 'his, her, its' (also 'their' of non-personal possessors)

- wáthu 'our'

- wánu 'your' (of you plural, or polite)

- wáo 'their' (or 'his, her' in polite speech)

The adjective wína ‘another, a certain’ has similar tones to wánga:

- wína (plural éna) 'another, a certain'

The adjective wamba ‘ordinary’, however, is not made with á and has a low tone on both syllables. The first syllable wa in this word does not change with the class of noun.

Pronominal adjectives

The following three adjectives have their own concords and are not formed using á. Here they are shown with the concords of classes 1 and 2:

- yénse (plural ónse) 'all of'

- yémwe (plural ómwe) 'himself'

- yékha (plural ókha) 'only'

As with possessives, the high tone of these may shift by bumping after a noun ending in HL or LH or HH.[48]

With these three the high tone also shifts before a demonstrative suffix: yemwé-yo ‘that same one’. zonsé-zi ‘all these’.[49] (In this they differ from wánga and wína, which do not shift the tone with a demonstrative suffix, e.g. anthu éna-wa ‘these other people’.) The tone also shifts in the word álí-yensé ‘each, each and every’, in which áli has the tones of a relative-clause verb.[50]

The following demonstrative adjectives (shown here with the concords for noun classes 1 and 2) usually have a low tone:[51]

- uyo (plural awo) 'that one'

- uyu (plural awa) 'this one'

- uno (plural ano) 'this one we're in'

- uja (plural aja) 'that one you mentioned'

- uti? (plural ati?) 'which one?'

The first of these (uyo), however, can be pronounced úyo! with a high tone if referring to someone a long way away.[52] The word uti/ati? can also acquire an intonational tone in certain types of questions (see below).

Numbers

Chichewa has the numbers 1 to 5 and 10. These all have penultimate high tone except for -sanu ‘five’, which is toneless. The adjectives meaning ‘how many?’ and ‘several’ also take the number concords and can be considered part of this group. They are here illustrated with the concords for noun classes 1 and 2 (note that khúmi has no concord):

- munthu mmódzi ‘one person’

- anthu awíri ‘two people’

- anthu atátu ‘three people’

- anthu anáyi ‘four people’

- anthu asanu ‘five people’

- anthu khúmi ‘ten people’

- anthu angáti? ‘how many people?’

- anthu angápo ‘several people’

The numbers zaná ‘100’ and chikwí ‘1000’ exist but are rarely used. It is possible to make other numbers using circumlocutions (e.g. ‘five tens and units five and two’ = 57) but these are not often heard, the usual practice being to use English numbers instead.

Personal pronouns

The first and second person pronouns are toneless, but the third person pronouns have a high tone:[53]

- ine ‘I’

- iwe ‘you sg.’

- iyé ‘he, she’

- ife ‘we’

- inu ‘you pl., you (polite)’

- iwó ‘they, he/she (polite)’

These combine with ndi as follows:

- ndine ‘I am’

- ndiyé ‘he is’ (etc.)

- síndine ‘I am not’

- síndíyé ‘he is not’

Monosyllables

The following monosyllabic words are commonly used. The following are toneless:

- ndi 'it is, they are'

- ku 'in, to, from'

- pa 'on, at'

- mu (m’) 'in'

The following have a high tone:

- á (also wá, yá, zá, kwá etc. according to noun class) 'of'

- ndí 'with, and'

- sí 'it isn't'

These words are joined rhythmically to the following word. The high tone can spread to the first syllable of the following word, provided it has at least three syllables:[54] They can also make a plateau with the following word, if the tones are HLH:

- Lilongwe 'Lilongwe' > á Lílongwe 'of Lilongwe'

- pemphero 'prayer' > ndí pémphero 'with a prayer'

- Maláwi > á Máláwi 'of Malawi'

The word pa has a tone when it means 'of' following a noun of class 16:

- pa bédi ‘on the bed’ but pansí pá bédi 'underneath (of) the bed'

It also has a tone in certain idiomatic expressions such as pá-yekha or pá-yékha 'on his own'.

Ideophones

The tones of ideophones (expressive words) have also been investigated by linguists.[55] Examples are: bálálábálálá ‘scattering in all directions’ (all syllables very high), lólolo ‘lots and lots’ (with gradually descending tones), bii! ‘very dark or dirty’ (low pitch). It can be seen that the tonal patterns of ideophones do not necessarily conform to the patterns of other words in the language.

Lexical tones of verbs

Chichewa verbs are mostly toneless in their basic form, although a few have a high tone (usually on the final vowel). However, unlike the situation with the lexical tones of nouns, there is no correlation at all between the high-toned verbs in Chichewa and the high-toned verbs in other Bantu languages. The obvious conclusion is that the high tones of verbs are not inherited from an earlier stage of Bantu but have developed independently in Chichewa.[56]

When a verbal extension is added to a high-toned root, the resulting verb is also usually high-toned, e.g.

- goná 'sleep' > gonaná 'sleep together'

Certain extensions, especially those which change a verb from transitive to intransitive, or which make it intensive, also add a tone. According to Kanerva (1990) and Mchombo (2004), the passive ending -idwa/-edwa also adds a high tone, but this appears to be true only of the Nkhotakota dialect which they describe.[57]

High-toned verb roots are comparatively rare (only about 13% of roots),[58] though the proportion rises when verbs with stative and intensive extensions are added. In addition there are a number of verbs, such as peza/pezá 'find' which can be pronounced either way. In the monolingual dictionary Mtanthauziramawu wa Chinyanja 2683 verbs are given, with 10% marked as high-toned, and 4% as having either tone. In the Southern Region of Malawi, some speakers do not pronounce the tones of high-toned verbs at all or only sporadically.

The difference between high and low-toned verbs is neutralised when they are used in a verb tense which has a high tone on the penultimate or on the final syllable.

Three irregular verbs, -téro 'do so', -tére 'do like this', and -táni? 'do what?', have a tone on the penultimate syllable.

The view held in Mtenje (1986) that Chichewa also has 'rising-tone' verbs has been dropped in his more recent work.[59]

Low-toned verbs

- bwera ‘come’

- chita ‘do’

- choka ‘go away’

- dziwa ‘know’

- fika ‘arrive’

- fotokoza ‘explain’

- funa ‘want’

- funsa ‘ask’

- ganiza ‘think’

- gula ‘buy’

- gulitsa ‘sell’

- gwira ‘take hold of’

- imba ‘sing’

- khala ‘sit, live’

- kumana ‘meet’

- lankhula/yankhula ‘speak’

- lemba ‘write’

- lowa ‘enter’

- mwalira 'die'

- nena ‘say’

- ona ‘see’

- panga ‘do, make’

- patsa ‘give (someone)’

- pereka ‘hand over’

- pita ‘go’

- seka ‘laugh’

- sintha ‘change’

- tenga ‘take’

- thandiza ‘help’

- uza ‘tell’

- vala ‘put on (clothes)’

- vuta ‘be difficult’

- yamba ‘begin’

- yankha ‘answer’

- yenda ‘go, walk’

Monosyllabic verbs such as the following are always low-toned, although nouns derived from them, such as imfá 'death', can have a tone:

- ba ‘steal’

- dya ‘eat’

- fa 'die'

- mva ‘hear’

- mwa ‘drink’

- pha ‘kill’

- tha ‘finish, be able’

High-toned verbs

- bisá ‘hide (something)’

- bisalá ‘be hidden’

- dabwá ‘be surprised’

- dandaulá ‘complain’

- goná ‘sleep’

- iwalá ‘forget’

- kaná ‘refuse’

- kondá ‘love’

- lakwá ‘be in error’

- lepherá ‘fail’

- phunzirá ‘learn’

- siyá ‘leave’

- tayá ‘throw away’

- thamangá ‘run’

- topá ‘be tired’

- tsalá ‘remain’

- vulazá ‘wound’

- yenerá ‘ought’

- zimá/thimá ‘go out (of fire or lights)’

Verbs with either tone

- ipá ‘be bad’

- khotá ‘be bent’

- kwiyá ‘be angry’

- namá ‘tell a lie’

- pewá ‘avoid’

- pezá ‘find’

- sowá ‘miss, be missing’

- thokozá ‘thank’

- yabwá ‘irritate, make itch’

Stative verbs

Most intransitive verbs with the endings -iká, -eká, -uká, -oká derived from simpler verb-stems are high-toned. This is especially true when a transitive verb has been turned by a suffix into an intransitive one:

- chitiká ‘happen’ (cf. chita ‘do’)

- duká ‘be cut’ (cf. dula ‘cut’)

- dziwiká ‘be known’ (cf. dziwa ‘know’)

- funiká ‘be necessary’ (cf. funa ‘want’)

- masuká ‘be at ease’ (cf. masula ‘free’)

- mveká ‘be understood’ (cf. mva ‘hear’)

- onongeká ‘be damaged’ (cf. ononga ‘damage’)

- theká ‘be possible’ (cf. tha ‘finish, manage to’)

- thyoká ‘be broken’ (cf. thyola ‘break’)

- vutiká ‘be in difficulty’ (cf. vutitsa ‘cause a problem for’)

However, there are some common exceptions such as the following which are low-toned:

- oneka 'seem' (cf. ona 'see')

- tuluka 'come out, emerge' (cf. tula 'remove a burden')

Intensive verbs

Intensive verbs with the endings -its(its)á and -ets(ets)á always have a high tone on the final syllable, even when derived from low-toned verbs. A few intensive verbs with the endings -irirá or -ererá are also high-toned:[60]

- yang’angitsitsá ‘examine carefully’ (cf. yang’ana ‘look at’)

- onetsetsá ‘inspect’ (cf. ona ‘see’)

- mvetsetsá ‘understand well’ (cf. mva ‘hear’)

- menyetsá ‘beat severely’ (cf. menya ‘hit’)

- pitirirá ‘go further’ (cf. pita ‘go’)

- psererá ‘be overcooked’ (cf. psa ‘burn, be ripe’)

Grammatical tones of verbs

In addition to the lexical tones which go with individual words, Chichewa also has grammatical tones which apply to verbs. Each different tense has its own tonal pattern, which is superimposed on top of whatever lexical tone the verb-stem itself may have. The tonal patterns, though numerous, are fewer than the number of tenses, so that often the same pattern is shared by three or four different tenses.

The principle of these patterns is that in any particular tense, the same tonal pattern is applied equally to every verb, with minor variations, however long or short.

Thus the Present Continuous tense (which uses -ku- as a tense-marker) always has a single high tone on the syllable immediately following the tense-marker. In longer verbs in some Central Region dialects this tone may spread forward one syllable:[61]

- ndi-ku-fótokoza (or ndi-ku-fótókoza) 'I am explaining'

- ndi-ku-wérenga 'I am reading'

- ndi-ku-óna 'I am seeing'

- ndi-ku-dyá (pronounced ndi-kú-dyá or ndi-kú-dya)[62] 'I am eating'

In the above examples, hyphens have been added for clarity; they are not used in the standard orthography.

On the other hand, the Present Habitual tense has a high tone on the initial syllable and another which is usually heard on the penultimate. But if the verb-stem is monosyllabic, in order to keep the two tones apart, the second tone is heard on the final syllable instead of the penultimate.[61] Because of downdrift, the second tone is slightly lower in pitch than the first.[63]

- ndí-ma-fotokóza 'I usually explain'

- ndí-ma-werénga 'I usually read'

- ndí-ma-óna 'I usually see'

- ndí-ma-dyá 'I usually eat' (but ndí-ma-mú-dya 'I usually eat it')

The Remote Perfect (past simple) tense of the same verbs (which uses -na- or -da- as a tense-marker) has a high tone on the tense-marker itself. This tone can also spread in longer verbs:

- ndi-ná-fotokoza (or ndi-ná-fótokoza) 'I explained'[64]

- ndi-ná-werenga (or ndi-ná-wérenga) 'I read'

- ndi-ná-ona 'I saw'

- ndi-ná-dya 'I ate'

An example of a toneless tense is the Perfect. In toneless tenses all the syllables are pronounced low, unless the verb-stem itself has a high tone:

- nd-a-fotokoza 'I have explained'

- nd-a-werenga 'I have read'

- nd-a-ona 'I have seen'

- nd-a-dya 'I have eaten'

Positive tenses

At least ten tonal patterns in all are used for the main verb tenses (more, if tenses with aspect-markers are included). Some of those which have been noted in the literature are:[65]

- Toneless:

- Perfect nda-thandiza ‘I have helped’

- Imperative thandiza! ‘help!’

- Potential ndi-nga-thandize ‘I can help’[66]

- High tone on subject-marker only:

- Present Simple / Near Future ndí-thandiza (or ndí-thándiza) ‘I will help’

- High tone on tense-marker only (which may spread):

- High tone on the syllable following the tense-marker:

- Infinitive ku-thándiza ‘to help’

- Present Continuous ndi-ku-thándiza ‘I am helping’

- Recent Past Continuous ndi-ma-thándiza ‘I was helping’

- Recent Past Simple ndi-na-thándiza ‘I helped (today)’

- Polite Imperative ta-thándiza! ‘please help’[69]

- High tone on penultimate only:

- Persistive ndi-kada-thandíza ‘I’m still helping’[70]

- High tone on final syllable:

- Subjunctive ndi-thandizé ‘I should help’

- High tones on subject-marker and tense-marker:

- Remote Future ndí-dzá-thandiza (or ndi-dzá-thandiza/ndi-dzá-thándiza) ‘I shall help’

- -ká-Future ndí-ká-thandiza ‘I shall help (when I get there)’

- High tones on subject-marker (without spreading) and penultimate:

- Present Habitual ndí-ma-thandíza ‘I usually help’

- High tones on subject-marker (with spreading in some dialects) and penultimate:

- Remote Past ndí-náa-thandíza ‘I (had) helped’ (This tense can also be made with -daa-.)

- ‘Meanwhile’ Subjunctive ndí-báa-thandíza ‘I should be helping meanwhile’[71]

- High tones on tense-marker and penultimate:

- Remote Past Continuous ndi-nká-thandíza ‘I used to help’

- Necessitive ndi-zí-thandíza ‘I should be helping’[72]

Negative tenses

Negative tenses in Chichewa tend to have a different tonal pattern from the corresponding positive ones.[73] In some tenses, the meaning changes according to the tones used.

Negative tenses in main clauses start with the negative marker sí-, which usually has a high tone. There is also usually a tone on the subject-marker. In the Negative Past Simple, which ends in -e, there is also a high tone on the penultimate syllable:

- sí-ndí-na-thandíze 'I didn't help / I haven't helped'[74]

The Present Simple has two negative intonations. When it has habitual meaning, there are tones on the first two syllables only; but when an object-marker is added an extra tone appears on the penultimate:

- sí-ndí-thandiza 'I don't help'

- sí-ndí-mu-thandíza 'I don't help him'[75]

In monosyllabic verbs, in the Central Region, the high tone on the subject-marker is omitted in this tense:

- sí-ndi-dya (Southern Region sí-ndí-dya) 'I don't eat'

When the Present Simple is used with a future meaning, the negative intonation is the same as for future tenses (see below).

In tenses which have a proclitic tense-marker, such as the Present Continuous, the Imperfect, and the Recent Past, the last tone is heard not on the penultimate syllable but immediately after the tense-marker:

- sí-ndí-ku-thándiza 'I'm not helping'

- sí-ndí-ma-thándiza 'I wasn't helping'

- sí-ndí-na-thándiza 'I didn't help just now' (rarely used)

All negative tenses which have a future or prospective meaning ('won't' or 'not yet') have a single tone on the penultimate syllable, other tones being suppressed. The negative infinitive, and the negative subjunctive, which are made with the negative marker -sa-, have the same intonation:

- si-ndi-(dza)-thandíza 'I won't help'

- si-ndi-na-thandíze 'I haven't helped yet'

- si-ndi-ná-dye 'I haven't eaten yet'

- ku-sa-thandíza 'not to help'

- ndi-sa-thandíze 'so that I shouldn't help'[76]

More complex intonations are found in negative tenses made with -ma-, -nka-,-nga-, and -kada-, where is a tone on the tense-marker as well:[77]

- sí-ndí-má-thandiza ‘I never help’

- sí-ndí-kadá-thandiza ‘I would not have helped’

- si-ndi-ngá-thandíze ‘I can't help’ (also sí-ndí-nga-thandíze[78])

- ku-sa-má-thandíza ‘to be never helping’

- sí-ndí-nká-thandíza ‘I didn't use to help’

- sí-ndí-má-mu-thandíza ‘I never help him’

Dependent clause tenses

Certain tenses in Chichewa are used only in dependent clauses. These include the following:

- Toneless:

- ‘When’ tense ndi-ka-thandiza ‘when/if I help’[79]

(This tense can be modified by the addition of aspect-markers, e.g. ndi-ka-má-thandíza 'whenever I help'.)

- High tones on subject-marker and after the tense-marker (usually bridging into a plateau):

- Participial Present ndí-kú-thándiza ‘while I am helping’

- Participial Perfect ndí-tá-thándiza ‘me having helped, after I helped’[80]

- High tones on the subject-marker (which may spread) and penultimate:

- Negative Perfect Participle ndí-sa-na-thandíze (or ndí-sá-na-) ‘before I help(ed)’[81]

- Negative Present Participle ndí-sa-ku-thandíza ‘without my helping’

- High tone on the penultimate only:

- 'Since' adverbial chi-thandizíre 'since helping'

In addition, certain tenses have a different tonal pattern when used in certain kinds of dependent clauses. Stevick calls this intonation the ‘relative mood’ of the verb,[82] since it is frequently used in relative clauses; however, it is also used in a range of other dependent clauses, such as conditional clauses, cleft sentences, and adverbial clauses of time, place, manner, and concession. However, clauses following kutí ‘that’ or ngati when it has the meaning ‘as if’ use the normal intonation. Often the use of relative clause intonation alone can show that a verb is being used in the meaning of a relative or conditional clause.[83]

The dependent-clause intonation generally has two high tones, one on the initial syllable and another on the penultimate. High tones between these two are suppressed. The first high tone may spread. When the tones are HLHL, some dialects have bumping; for example, ndí-na-gúla ‘(which) I bought’ can become ndí-ná-gulá.[84]

- a-ná-thandiza ‘he helped’ becomes á-na-thandíza (or á-ná-thandíza)

- wa-thandiza ‘he has helped' becomes wá-thandíza (or when used as a noun or adjective wá-thándíza)

- ndi-nga-thandize ‘I can help’ becomes ndí-nga-thandíze[85]

But when the tense has a proclitic prefix the second high tone comes on the syllable after the tense-marker. There is usually bridging of the two tones:[86]

- améné á-kú-thándiza 'who is helping'

- améné á-má-thándiza 'who was helping'

If the verb has only one syllable, the second high tone is dropped:

- mwezí wá-tha ‘the month which has finished, i.e. last month’[87]

- mvúlá íli kugwá ‘when rain is falling’[88]

If the verb tense already has a high tone on the initial syllable, such as the Present Simple, Present Habitual, and Remote Future, there is no change. Negative tenses, such as s-a-na-thandíze ‘he hasn't helped yet’, are also unaltered when used in dependent clauses.

Questions with ndaní? 'who?' and nchiyáni? 'what?' are expressed as Cleft sentences, using relative clause intonation:

- wákhálá pa-mpando ndaní? ‘who is the one sitting on the chair?’ (lit.'(he) who has sat on the chair is who?')

The dependent clause intonation is also used in conditional clauses, except those with the toneless -ka- tense. An example can be observed in the following proverb, where the dependent verb has a different intonation from the main verb:

- ndíkanadzíwa, ndikanáphika thereré ‘If I'd known (that you were going to come back from the hunt with nothing), I’d have cooked some vegetables!’[89]

It is similarly used in indirect questions after ngati ‘if’ and in clauses after ngakhále 'although':

- sízíkudzíwíká ngati wámwalíra (or wámwálirá) ‘it isn't known if she has died’

- ngakhálé mvúla íkubvúmba ‘even when rain is falling’[90]

Tones of -li (‘am’, ‘are’, ‘is’)

As well as the word ndi ‘is/are’ used for identity (e.g. ‘he is a teacher’) Chichewa has another verb -li ‘am, are, is’ used for position or temporary state (e.g. ‘he is well’, ‘he is in Lilongwe’). The tones of this are irregular in that in the Present Simple, there is no tone on the subject-marker.[91] For the Remote Past, both á-naa-lí and a-ná-li[92] can be heard, apparently without difference of meaning. In the dependent Applied Present (-lili), used in clauses of manner, the two tones make a plateau:

- In main clauses:

- Present a-li ‘he is, they are’

- Recent Past a-na-lí ‘he was (just now)’

- Remote Past á-náa-lí or a-ná-li ‘he was’

- Persistive a-kadá-li (or a-ka-lí) ‘he is still’

- In dependent clauses:

- Present á-li ‘when he is/was’

- Persistive á-kada-lí ‘when he is/was still’[93]

- Applied Present momwé á-lílí ‘the way that he is’

The dependent-clause form of the Persistive tense is frequently heard in the phrase pá-kada-lí pano ‘at the present time’ (literally, ‘it still being now’).

Aspect-markers

After the tense-marker, there can be one or more aspect-markers, which add precision to the meaning of the tense. Altogether there are four aspect-markers, -má- ‘ever, usually, always’, -ká- ‘go and’, -dzá- ‘in future’, and -ngo- ‘just’, which are always added in that order, though not usually all at once. These infixes add extra high tones to the verb.

-má-

The aspect-marker -má- ‘always, ever, generally’ usually adds two high tones, one on -má- itself and one on the penultimate syllable. For example, when added to the ‘when’ tense, which has the toneless tense-marker -ka- (not to be confused with the aspect-marker -ká-):

- ndi-ka-má-thandíza ‘whenever I help’

However, in the Present Habitual, the tone on -má- is lost:

- ndí-ma-mu-thandíza ‘I usually help him’

It is also lost in negative future tenses:

- si-ndi-ma-dza-thandíza ‘I won’t be always helping’

On the other hand, in the negative Present Habitual, the tone on -má- is retained while the penultimate tone is lost, unless there is an object-marker:

- sí-ndí-má-thandiza ‘I am not usually helping’[94]

- sí-ndí-má-mu-thandíza ‘I don’t usually help him’

-má- can also be used as a tense-marker itself to make the Imperfect tense, in which case its high tone is proclitic:

- ndi-ma-thándiza ‘I was helping’

- sí-ndí-ma-thándiza ‘I wasn't helping’[95]

-ká- and -dzá-

The aspect-markers -ká- ‘go to’ and -dzá- ‘in future’ or ‘come to’ have the same tones as each other. In the Remote Perfect, the tone is high, and sometimes spreads:[96]

- ndi-ná-ká-thandiza (or ndi-ná-ká-thándiza) ‘I went to help’

This tone (unlike the tone of -mu-) does not undergo bumping when the tones are HHL:[97]

- ti-ná-ká-pha ‘we went and killed’

In tenses which have a tone on the penultimate, -ká- and -dzá- lose their tone:

- ndí-ma-ka-thandíza ‘I (always) go to help’

- sí-ndí-na-ka-thandíze ‘I didn't go to help’

- si-ndi-dza-píta ‘I won’t go’[98]

- ku-sa-ka-thandíza ‘not to go and help’[99]

The high tone is also lost in the Imperative, where there is a tone on the final syllable only:

- ka-thandizé ‘go and help!’

- ka-dyé ‘go and eat!’[100]

But in the positive Subjunctive -ká- and -dzá- retain their tone, and there is a second tone on the penultimate which does not bump to the final:

- ndi-ká-thandíze ‘I should go and help’.

-ngo-

The aspect-marker -ngo- ‘just’ is derived from the infinitive, and like the infinitive it is proclitic, that is to say, there is a high tone on the syllable after -ngo-. (The syllable -ngo- itself is always toneless.)

In toneless tenses, the syllables before it are toneless:

- i-ngo-bwéra! ‘just come!’

- nda-ngo-bwéra ‘I have just come’

In all other tenses, -ngo- also has a high tone in front of itself:

- ndí-má-ngo-thándiza ‘I usually just help’

If -ngo- is added to a proclitic tense such as the Present Continuous, the tense-marker keeps its high tone and is no longer proclitic:

- ndi-ku-thándiza ‘I'm helping’

- ndi-kú-ngo-thándiza ‘I'm just helping’

Object-markers

With toneless tenses

Between the aspect-markers and the verb stem, it is possible to add an object-marker such as -mú- ‘him/her/it’ or -zí- 'those things' etc. When an object-marker is added to a toneless tense, such as the Perfect, it has a high tone:[101]

- nda-mú-thandiza ‘I have helped him’

- ndi-ka-mú-thandiza ‘if I help him’

- ndi-nga-mú-thandize ‘I can help him’[102]

With penultimate-tone tenses

However, in tenses which have penultimate tone the object-marker is toneless, unless the penultimate tone coincides with the object-marker itself:

- ndí-ma-mu-thandíza ‘I usually help him’[103]

- mu-sa-mu-thandíze ‘do not help him’[104]

- ndí-ma-mú-dya ‘I usually eat it’ (e.g. sugar)

With the Remote Perfect

In the Remote Perfect (Past Simple) tense, which has the tense-marker -ná- or -dá-, the tone of the object-marker is lost in southern dialects.[105] In dialects with high tone spreading, the object-marker has a high tone, but it is thought that this tone is due to spreading, as it does not spread further to the following syllable, unlike the tone of -ká-.[106]

- ndi-ná-mu-thandiza 'I helped him' (southern speakers)

- ti-ná-mú-thandiza 'we helped him' (Central Region)

With monosyllabic verb-stems, the high tone of -mú- is retained and (unlike the tone of -ká-) undergoes bumping, making a plateau:[107]

- ti-ná-mú-phá 'we killed him'

With proclitic tenses

Where the tense-marker or aspect-marker has proclitic tone, for example in the infinitive, Present Continuous, or Recent Past, the rules stated above apply; that is to say, there is an additional tone on the penultimate in longer verbs, or on the final in verbs of 2 or 3 syllables:

- ku-mú-fotokozéra 'to explain to him'

- ku-mú-thandizá 'to help him'

With the imperative

In an Imperative verb the high tone of the object-marker becomes proclitic and is heard on the syllable which follows it. The final vowel changes to -e and has a tone. There is a plateau if the verb stem has three syllables:[108]

- mu-fótokozeré 'explain to him'

- mu-thándízé 'come and help him'

The addition of -ka- or -dza-, which are toneless in the Imperative, does not affect this:

- dza-mu-thándízé 'come and help him'

If the verb has two syllables, the tone on the final is dropped by Meeussen's rule:

- (ndi-)pátse-ni 'give me!'

If the verb is monosyllabic, the tone remains on -mú-, and the high tone of the final vowel is dropped:

- mú-dye ‘eat it!’[109]

When the imperative is preceded by the aspect-markers ta- ('do it now!') or i-ngo- ('just do it!'), which are proclitic, the rules for proclitic verbs given above apply:

- i-ngo-mú-thandizá! 'just help him!'

- ta-ndí-fotokozéra! 'explain to me now please'

With the subjunctive

In the Subjunctive, the same tones apply, unless -ká- or -dzá- is added:

- ndi-mu-thándízé 'let me help him'

But when -ká- or -dzá- is added, the object-marker loses its tone, and the second tone is heard on the penultimate:

- mu-dzá-mu-thandíze 'you should come and help him'

Reflexive-marker

The reflexive-marker -dzí- in most dialects has exactly the same tones as object-markers such as -mú-, but for some speakers in parts of the Central Region there is also an extra tone on the penultimate or final syllable.[110]

- a-ná-dzí-thandiza ‘he helped himself’ (Lilongwe)

- a-ná-dzí-thandíza ‘he helped himself’ (Nkhotakota)

Intonational tones

In addition to the ordinary lexical tones which go with individual words, and the grammatical tones of verb tenses, other tones can be heard which show phrasing or indicate a question.

Boundary tones

Quite often, if there is a pause in the middle of sentence, the speaker's voice will rise on the syllable just before the pause. This rising tone is called a boundary tone.[111] A boundary tone is used after the topic of a sentence, at the end of a dependent clause, after items on a list, and so on. A typical sentence where the dependent clause precedes the main clause is the following:

- mu-ka-chí-kónda↗, mu-chi-gúle[112] ‘if you like it, you should buy it’

The rising boundary tone is not used when the order is reversed and the dependent clause follows the main clause.[113]

Another kind of tone considered to be a boundary tone, but this time a low one, is the optional fall in the speaker's voice at the end of sentences which causes the final high tone on words like chákúdyá ‘food’ to drop.

Both Kanerva and Stevick also mention a ‘level’ boundary tone, which occurs mid-sentence, but without any rise in pitch.[114]

Tones of questions

Wh-Questions

Questions in Chichewa often add high tones where an ordinary statement has no tone. For example, with the word kuti? ‘where?’, liti ‘when?’, yani ‘who?’ or chiyáni ‘what?’ some people add a tone on the last syllable of the preceding word. This tone does not spread backwards, although it may form a plateau with an antepenultimate tone, as in the 3rd and 4th examples below:

- alí kuti? ‘where is he?’[115]

- ndiwé yani? ‘who are you?’

- mu-ná-fíká liti? ‘when did you arrive?’[116]

- mu-ká-chítá chiyáni? ‘what are you going to do there?’[117]

But as Stevick points out, not all speakers do this, and others may say mu-ná-fika liti?[118]

When kuti? ‘which place?’ or liti? ‘which day?’ are preceded by ndi ‘is’, they take a high tone on the first syllable:

- kwánú ndi kúti? ‘where is your home?’[119]

It appears that with some speakers the high tone after ndi is heard on the final syllable in forms of this adjective which begin with a vowel; but with other speakers it is heard on the first syllable:[120]

- mipando yáikúlu ndi ití? ‘which are the large chairs?’

- msewu wópíta ku Blántyre ndi úti? ‘which is the road going to Blantyre?’

A high tone also goes on the final syllable in ndaní? ‘(it is) who?’ (which is derived from ndi yani?)[121] Before this word and nchiyáni? ‘(is) what?’, since such questions are phrased as a cleft sentence or relative clause, the verb has its relative-clause intonation:

- wákhálá pampando ndaní? ‘(the one who is) sitting on the chair is who?’, i.e. ‘who is it who's sitting on the chair?’

The relative-clause intonation of the verb is also used when a question begins with bwánji? 'how come?', but not when it ends with bwánji?, when it has the meaning 'how?'

Yes-no questions

With yes-no questions, intonations vary. The simplest tone is a rising boundary tone on the final syllable:

- mwa-landirá? ‘did you receive it?’[122]

A more insistent question often has a HL falling boundary tone on the last syllable:[123]

- mwa-landirâ? ‘did you receive it?’

But in other dialects, this fall may begin on the penultimate syllable:

- ku Zómba? ‘in Zombá?’[124]

If there is already a penultimate high tone it may simply be raised higher:

- ku Baláka? ‘in Baláka?’[125]

Sometimes, however, there is no particular intonational tone and the question has the same intonation as a statement, especially if the question starts with the question-asking word kodí.[126]

Other idiomatic tones

Some speakers add intonational tones also with the word kale ‘already’, making not only the final syllable of kale itself high but also the last syllable of the verb which precedes it:

Other speakers do not add these intonational tones, but pronounce ndavina kale with Low tones.

Occasionally a verb which is otherwise low-toned will acquire a high tone in certain idiomatic usages, e.g. ndapitá ‘I'm off’ (said on parting), from the normally toneless pita ‘go’. This can perhaps also be considered a kind of intonational tone.

Focus and emphasis

In European languages it is common for a word which is picked out for contrast to be pronounced on a higher pitch than the other words in a sentence, e.g. in the sentence they fed the baboon fish, not the elephant, it is likely that the speaker will draw attention to the word baboon by pronouncing it on a high pitch, while the word fish, which has been mentioned already, will be on a low pitch. This kind of emphasis is known as 'focus'. In tonal languages it appears that this raising or lowering of the pitch to indicate focus is either absent or much less noticeable.[129]

A number of studies have examined how focus is expressed in Chichewa and whether it causes a rise in pitch.[130] One finding was that for most speakers, focus has no effect on pitch. For some speakers, however, it appears that there is a slight rise in pitch if a word with a tone is focussed.[131] A toneless word, when in focus, does not appear to rise in pitch.

A different kind of emphasis is emphasis of degree. To show that something is very small, or very large, or very distant, a Chichewa-speaker will often raise the pitch of his or her voice considerably, breaking the sequence of downdrift. For example, a word such as kwámbíri 'very much' or pang'óno 'a little' is sometimes pronounced with a high pitch. The toneless demonstrative uyo ‘that man’ can also acquire a tone and become úyo! with a high pitch to mean ‘that man over there in the distance’.[132]

Tonal minimal pairs

Sometimes two nouns are distinguished by their tone patterns alone, e.g.

- mténgo ‘tree’ vs mtengo ‘price’

- khúngu ‘blindness’ vs khungú ‘skin’

Verbs can also sometimes be distinguished by tone alone:

- ku-lémera ‘to be rich’ vs ku-lémérá ‘to be heavy’

- ku-pwéteka ‘to hurt’ vs ku-pwétéká ‘to be hurt’

There is also a distinction between:

- ndi ‘it is’ vs ndí ‘and, with’

However, minimal pairs of this kind which differ in lexical tone are not particularly common.

More significant are minimal pairs in verbs, where a change of tones indicates a change in the tense, or a difference between the same tense used in a main clause and in a subordinate clause, for example:

- ndí-ma-werénga ‘I usually read’ vs ndi-ma-wérenga ‘I was reading’

- sá-na-bwére ‘he did not come’ vs sa-na-bwére ‘he has not come yet’

- ndi-kaná-pita ‘I would have gone’ vs ndí-kana-píta ‘if I had gone’

- chaká chatha ‘the year has finished’ vs chaká chátha ‘last year’

- ndí-kana-dzíwa ‘if I had known’ vs ndi-kaná-dziwa ‘I would have known’

Reduplicated words

Reduplicated words are those in which an element is repeated, such as chipolopolo ‘bullet’. These have been extensively studied in the literature.[133]

Reduplication in nouns

In nouns, adjectives, and adverbs, ordinary reduplication can be distinguished from emphatic reduplication, since the tones differ, as is shown below (note that hyphens have been added here for clarity, but are not used in the standard orthography of Chichewa).

LL + LL becomes LLLL (i.e. there is no additional tone):

- chi-ng’ani-ng’ani ‘lightning’

- chi-were-were ‘sex outside marriage’

LH + LH becomes LHLL (i.e. the second tone is dropped):

- chi-masó-maso ‘adultery’

- m-lengá-lenga ‘sky, atmosphere’

- chi-bolí-boli ‘wooden carving’

HL + HL becomes HLLH (or HHLH), by ‘bumping’:

- chi-láko-lakó (or chi-lákó-lakó) ‘desire’

- chi-thúnzi-thunzí (or chi-thúnzí-thunzí) ‘picture’

- a-múna-muná (or a-múná-muná) ‘real men’

Reduplication in adverbs

When adverbs are reduplicated, however, and there is an element of emphasis, the first two types have an added tone. Thus:

LL + LL becomes LLHL (i.e. there is an additional high tone on the second element):

- bwino-bwíno ‘very carefully’

- kale-kále ‘long ago’ (or ‘far off in the future’)

LH + LH is also different when emphatic, becoming LHHH (or in the Southern Region HHHH):

- kwení-kwéní (or kwéní-kwéní) ‘really’[134]

- okhá-ókhá (or ókhá-ókhá) ‘only, exclusively’

When a three-syllable element is repeated, there is no special change:

- pang’óno-pang’óno ‘gradually’

- kawíri-kawíri ‘often’

Reduplication in verbs

A high tone following a proclitic tensemarker does not repeat when the verb is reduplicated:[135]

- ku-thándiza-thandiza ‘to help here and there’

However, a final or penultimate tone will usually repeat (unless the verb has only two syllables, in which case the middle tone may be suppressed):[136]

- ti-thandizé-thandizé ‘let’s help here and there’

- ndí-ma-thandíza-thandíza ‘I usually help here and there’

- á-ma-yenda-yénda ‘they move about here and there’

Reduplication in ideophones

Ideophones (expressive words) have slightly different types of reduplication. Moto (1999) mentions the following types:

All High:

- góbédé-góbédé (noise of dishes clattering)

- bálálá-bálálá (scattering of people or animals in all directions)

All low:

- dzandi-dzandi (walking unsteadily)

High on the first syllable only:

- chéte-chete (in dead silence)

See also

References

- ↑ cf. Cruttenden (1986), p. 13.

- ↑ Kanerva (1990), pp. 12-14.

- ↑ Downing et al. (2004), p. 174.

- ↑ Cf. Downing & Pompino-Marschall (2013), pitchtrack (17).

- ↑ E.g. Mchombo (2004).

- ↑ Moto (1983), p. 206; Mtenje (1986), p. 206; Stevick et al. (1965), p. 20.

- ↑ Mchombo (2004), p. 11.

- ↑ Mtanthauziramawu wa Chinyanja (c.2000), p. vi.

- ↑ e.g. Kulemeka (2002), p. 15.

- ↑ Myers (1998).

- ↑ Hyman (2000).

- ↑ e.g. Kanerva (1990); cf. Mtenje (1976), pp. 212f.

- ↑ Kanerva (1990), pp. 12-14.

- ↑ Clark (1988), pp. 51ff.

- ↑ Hyman (2009).

- ↑ Watkins (1937).

- ↑ Stevick, Earl et al. (1965) Chinyanja Basic Course

- ↑ Scotton & Orr (1980) Learning Chichewa.

- ↑ Mtanthauziramawu wa Chinyanja (c.2000); Kishindo (2001), pp. 277-79; Kamwendo (1999).

- ↑ Mtenje (2001).

- ↑ Myers (1996); see also Myers (1999a).

- ↑ Yip (2002), p. 148.

- ↑ Myers (1996), pp. 36ff.

- ↑ Cf. Mtenje (1986), p. 240 vs. Mtenje (1987), p. 173.

- ↑ Myers (1999b).

- ↑ Kanerva (1990), p. 59; Mchombo (2004), p. 22.

- ↑ Moto (1983), p. 207.

- ↑ Moto (1983), p. 204.

- ↑ Mchombo (2004), p. 24.

- ↑ cf. Stevick et al. (1965), p. 194.

- ↑ Kanerva (1990), pp. 151-215.

- ↑ Hyman & Mtenje (1999a), p. 100.

- ↑ Moto (1983).

- ↑ Mchombo (2004), p. 17.

- ↑ Stevick et al. (1965), p. 111.

- ↑ Hyman & Mtenje (1999a), p. 102.

- ↑ Mtenje (1986), p. 240.

- ↑ Hyman & Mtenje (1999a), p. 104.

- ↑ Trithart (1976), p. 267.

- ↑ Kanerva (1990), p. 71, 66, 70; cf. Stevick p. 111.

- ↑ Stevick et al. (1965), p. 83.

- ↑ Mtenje (2001).

- ↑ Hyman & Mtenje (1999b), p. 121.

- ↑ Kanerva (1990), p. 39.

- ↑ Stevick et al. (1965), p. 119.

- ↑ Stevick et al. (1976), p. 176.

- ↑ Stevick et al. (1965), p. 155, cf. p. 101-2, 214.

- ↑ Kanerva (1990), p. 175.

- ↑ Stevick et al. (1965), pp. 69, 101.

- ↑ Kanerva (1990), p. 177.

- ↑ Stevick et al. (1986), pp. 248-9.

- ↑ Kulemeka (2002), p. 91.

- ↑ Stevick et al. (1965), p. 163, 165.

- ↑ Moto (1983), pp. 204f.

- ↑ Moto (1999).

- ↑ Hyman & Mtenje (1999b), p. 122f.

- ↑ Kanerva (1990), pp. 16-17; see Hyman & Mtenje (1999b), p. 127.

- ↑ Hyman & Mtenje (1999b), p. 124.

- ↑ Mtenje (1986), pp. 169, 206f.

- ↑ Hyman & Mtenje (1999b), p. 135.

- 1 2 Mtenje (1986), pp. 203–4.

- ↑ Mtenje (1986), p. 272.

- ↑ See the voice-track in Myers (1986), p. 83.

- ↑ Mtenje (1986), p. 195; (1987), p. 173.

- ↑ See especially Mtenje (1987).

- ↑ Stevick et al. (1965) p. 89.

- ↑ This tense can also be made with -dá-.

- ↑ Watkins (1937), p. 84.

- ↑ Stevick et al. (1965), p. 111.

- ↑ Watkins (1937), p. 100.

- ↑ Mchombo (2004), p. 32; Mtenje (1987) p. 194.

- ↑ Kanerva (1990), p. 22.

- ↑ For different negative tenses see Mtenje (1986), p. 244ff; Mtenje (1987), p. 183ff; Kanerva (1990), p. 23.

- ↑ Mtenje (1987), p. 183.

- ↑ cf. Stevick et al. (1965), p. 124, p. 243.

- ↑ Stevick et al. (1965), p. 222.

- ↑ Mtenje (1965), p.245.

- ↑ Stevick at al. (1965), p. 198.

- ↑ Kanerva (1990) p. 24.

- ↑ Kanerva (1990), p. 22.

- ↑ Kanerva (1990), p. 146.

- ↑ Stevick et al. (1965), p. 147.

- ↑ Mchombo (2004), pp. 17–18.

- ↑ Downing & Mtenje (2011), p. 9; Stevick et al. (1965), p. 148.

- ↑ Stevick et al. (1965), p. 196.

- ↑ But cf. Stevick (1965), p. 159.

- ↑ Stevick et al. (1965), p. 168.

- ↑ Stevick et al. (1965), p. 291.

- ↑ Chakanza, J.C. (2000). Wisdom of the People: 2000 Chinyanja Proverbs. CLAIM Blantyre (Malawi) p. 241.

- ↑ Stevick et al. (1965), p. 287.

- ↑ Stevick et al. (1965), p.1.

- ↑ Stevick et al. (1965), p. 156.

- ↑ Watkins (1937), p. 100.

- ↑ Mtenje (1986), p. 245.

- ↑ Mtenje (1986), p. 246.

- ↑ Hyman & Mtenje (1999a), p. 104.

- ↑ Hyman & Mtenje (1999a), p. 126.

- ↑ Mtenje (1986), p. 274.

- ↑ Hyman & Mtenje (1999a), p. 101.

- ↑ Kanerva (1990) p. 44 (with pausal form).

- ↑ Kanerva (1990), p. 24.

- ↑ Stevick et al. (1965), p. 197.

- ↑ Stevick at al. (1965), p. 264.

- ↑ Kanerva (1990), p. 33.

- ↑ Mtenje (1986), pp. 240-41.

- ↑ Hyman & Mtenje (1999a), p. 104.

- ↑ Hyman & Mtenje (1999a), p. 126.

- ↑ Mtenje (1995), p. 7; Stevick et al. (1965), p. 222.

- ↑ Mtenje (1995), p. 23; Kanerva (1990), p. 44.

- ↑ Hyman & Mtenje (1999a), pp. 103, 127.

- ↑ Myers (1996), pp. 29-60.

- ↑ Kanerva (1990), p. 147.

- ↑ Kanerva (1990), pp.138ff.

- ↑ Kanerva (1990), p.138; Stevick et al. (1965), p. 21.

- ↑ Stevick et al. (1965), p. 201.

- ↑ Stevick et al. (1965), p. 15.

- ↑ Stevick et al. (1965), p. 31.

- ↑ Stevick et al. (1965), p. 26.

- ↑ Stevick et al. (1965), p. 12.

- ↑ Stevick et al. (1965), pp. 254-6.

- ↑ Stevick et al. (1965), p. 268.

- ↑ cf. Myers (1996), p. 35; Hullquist, C.G. (1988) Simply Chichewa, p. 145.

- ↑ Downing (2008), p. 61; cf. Hullquist, C.G. (1988) Simply Chichewa, p. 145.

- ↑ Stevick et al. (1965), p. 34, 48, 53, 54.

- ↑ Stevick et al. (1965), pp. 225, 19.

- ↑ Stevick et al. (1965), pp. 42, 47, 75, 119.

- ↑ Stevick et al. (1965), p. 176.

- ↑ Stevick et al. (1965), p. 15.

- ↑ Cruttenden (1986), pp. 10ff; Downing (2008).

- ↑ Kanerva (1990); Myers (1996); Downing (2004); Downing (2008).

- ↑ Downing & Pompino-Marschall (2005).

- ↑ Kulemeka (2002), p. 91.

- ↑ Mtenje (1988); Kanerva (1990), pp. 37, 49-54; Hyman & Mtenje (1999a), pp. 107-124; Myers & Carleton (1996); Moto (1999).

- ↑ Stevick et al. (1965), p. 66.

- ↑ Hyman & Mtenje (1999a), pp. 107, 114.

- ↑ Stevick et al. (1965), p. 301.

Bibliography

- Botne, Robert D. & Andrew Kulemeka (1991). A learner’s Chichewa-English, English-Chichewa dictionary. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag.

- Clark, Mary (1988). "An Accentual Analysis of the Zulu Noun", in Harry van der Hulst & Norval Smith, Autosegmental Studies in Pitch Accent. Dordrecht: Foris.

- Cibelli, Emily (2012). "The Phonetic Basis of a Phonological Pattern: Depressor Effects of Prenasalized Consonants". UC Berkeley Phonology Lab Annual Report, 55-71. (Now published in Joaquín Romero, María Riera (2015) The Phonetics–Phonology Interface: Representations and methodologies, 335, 171-192.)

- Cruttenden, Alan (1986). Intonation. Cambridge University Press.

- Downing, Laura J. (2008). "Focus and Prominence in Chichewa, Chitumbuka, and Durban Zulu", ZAS Papers in Linguistics 49, 47-65.

- Downing, Laura J., Al D. Mtenje, & Bernd Pompino-Marschall (2004). "Prosody and Information Structure in Chichewa", ZAS Working Papers in Linguistics 37, 167-186.

- Downing, Laura J. & Bernd Pompino-Marschall (2005). "The focus prosody of Chichewa and the Stress-Focus constraint: a response to Samek-Lodovici (2005)". Natural language and linguistic theory, 31 (3) pp. 647–681.

- Downing, Laura J. & Al D. Mtenje (2011). "Un-WRAP-ping prosodic phrasing in Chichewa", in Nicole Dehé, Ingo Feldhausen & Shinichiro Ishihara (eds.). The Phonology-Syntax Interface, Lingua 121, 1965–1986.

- Downing, Laura J. & Bernd Pompino-Marschall (2013). "The focus prosody of Chichewa and the Stress-Focus constraint: a response to Samek-Lodovici (2005)". Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, Volume 31, Issue 3, pp 647–681.

- Hyman, Larry M. & Al D. Mtenje (1999a). "Prosodic Morphology and tone: the case of Chichewa" in René Kager, Harry van der Hulst and Wim Zonneveld (eds.) The Prosody-Morphology Interface. Cambridge University Press, 90-133.

- Hyman, Larry M. & Al D. Mtenje (1999b). "Non-Etymological High Tones in the Chichewa Verb", Malilime: The Malawian Journal of Linguistics no.1.

- Hyman, Larry M. (2000). "Privative Tone in Bantu". Paper presented at the Symposium on Tone ILCAA, Tokyo, December 12–16, 2000.

- Hyman, Larry M. (2007). "Tone: Is it Different?". Draft prepared for The Handbook of Phonological Theory, 2nd Ed., Blackwell (John Goldsmith, Jason Riggle & Alan Yu, eds)

- Hyman, Larry M. (2008). "How (not) to do phonological typology: The case of pitch accent". Language Sciences, 31 (2), 213-238.

- Kamwendo, Gregory H. (1999). "Work in Progress: The Monolingual Dictionary Project in Malawi", Malilime: The Malawian Journal of Linguistics no.1.

- Kanerva, Jonni M. (1990). Focus and Phrasing in Chichewa Phonology. New York, Garland.

- Kishindo, Pascal, 2001. "Authority in Language: The Role of the Chichewa Board (1972–1995) in Prescription and Standardization of Chichewa". Journal of Asian and African Studies, No. 62.

- Kulemeka, Andrew T. (2002). Tsinde: Maziko a Galamala ya Chichewa, Mother Tongue editions, West Newbury, Massachusetts.

- Mchombo, Sam (2004). Syntax of Chichewa. Cambridge University Press.

- Mchombo, Sam; Moto, Francis (1981). "Tone and the Theory of Syntax". In W.R. Leben (ed.) Précis from the 12th Conference on African Linguistics, Stanford University, pp. 92-95.

- Moto, Francis (1983). "Aspects of Tone Assignment in Chichewa", Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 3:1.

- Moto, Francis (1999). "The tonal phonology of Bantu ideophones", in Malilime: The Malawian Journal of Linguistics no.1, 100-120.

- Mtanthauziramawu wa Chinyanja/Chichewa: The first Chinyanja/Chichewa monolingual dictionary (c2000). Blantyre (Malawi): Dzuka Pub. Co. (Also published online at the website of the Centre for Language Studies of the University of Malawi.)

- Mtenje, Al D. (1986). Issues in the Non-Linear Phonology of Chichewa part 1. Issues in the Non-Linear Phonology of Chichewa part 2. PhD Thesis, University College, London.

- Mtenje, Al D. (1987). "Tone Shift Principles in the Chichewa Verb: A Case for a Tone Lexicon", Lingua 72, 169-207.

- Mtenje, Al D. (1988). "On Tone and Transfer in Chichewa Reduplication". Linguistics 26, 125-55.

- Mtenje, Al D. (1995). "Tone Shift, Accent and the Domains in Bantu: the Case of Chichewa", in Katamba, Francis. Bantu Phonology and Morphology: LINCOM Studies in African Linguistics 06.

- Mtenje, Al D. (2001). Common Bantu On-Line Dictionary (CBOLD) Chichewa Dictionary. This is an abridged version of Clement Scott and Alexander Hetherwick’s 1929 Dictionary of the Nyanja Language, with tones added by Al Mtenje. It is unfortunately not currently available.

- Myers, Scott (1988). "Surface Underspecification of Tone in Chichewa", Phonology, Vol. 15, No. 3, 367-91.

- Myers, Scott (1996). "Boundary tones and the phonetic implementation of tone in Chichewa", Studies in African Linguistics 25, 29-60.

- Myers, Scott (1999a). "Downdrift and pitch range in Chichewa intonation", Proceedings of the 14th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences, vol. 3, pp. 1981–4.

- Myers, Scott (1999b). "Tone association and f0 timing in Chichewa", Studies in African Linguistics 28, 215-239.

- Myers, Scott (2004). "The Effects of Boundary Tones on the f0 Scaling of Lexical Tones". In Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium on Tonal Aspects of Languages 2014, pp. 147–150.

- Myers, Scott & Troi Carleton (1996). "Tonal Transfer in Chichewa". Phonology, vol 13, (1) 39-72.

- Scotton, Carol Myers & Gregory John Orr, (1980). Learning Chichewa, Bk 1. Learning Chichewa, Bk 2. Peace Corps Language Handbook Series. Peace Corps, Washington, D.C.

- Stevick, Earl et al. (1965). Chinyanja Basic Course. Foreign Service Institute, Washington, D.C.

- Trithart, Lee (1976). "Desyllabified noun class prefixes and depressor consonants in Chichewa", in L.M. Hyman (ed.) Studies in Bantu Tonology, Southern California Occasional Papers in Linguistics 3, Los Angeles, CA: University of Southern California, 259-86.

- Watkins, Mark Hanna (1937). A Grammar of Chichewa: A Bantu Language of British Central Africa, Language, Vol. 13, No. 2, Language Dissertation No. 24 (Apr.-Jun., 1937), pp. 5–158.

- Yip, Moira (2002). Tone. Cambridge University Press.