Charles Algernon Parsons

| Sir Charles Algernon Parsons | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

13 June 1854 London, England, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland |

| Died |

11 February 1931 (aged 76) Kingston Harbour, Jamaica, |

| Nationality | British |

| Fields | Engineering |

| Institutions | Heaton, Newcastle |

| Alma mater |

Trinity College, Dublin St. John's College, Cambridge |

| Known for | Steam turbine |

| Notable awards |

Rumford Medal (1902) Albert Medal (1911) Franklin Medal (1920) Faraday Medal (1923) Copley Medal (1928) Bessemer Gold Medal (1929) |

| Spouse |

Katharine Bethell (m. 1883) (d. 1933) |

| Children |

Rachel Mary Parsons (1885–1956) Algernon George Parsons (b. 1886–1918) |

Sir Charles Algernon Parsons, OM, KCB, FRS (13 June 1854 – 11 February 1931), the son of a member of the Irish peerage,[1] was an Anglo-Irish engineer, best known for his invention of the compound steam turbine.[2] He worked as an engineer on dynamo and turbine design, and power generation, with great influence on the naval and electrical engineering fields. He also developed optical equipment, for searchlights and telescopes.

Biography

Parsons was born in London into an Anglo-Irish family,[3][4][5] youngest son of the famous astronomer William Parsons, 3rd Earl of Rosse. The family seat is Birr Castle, County Offaly, Ireland, and the town of Birr was called Parsonstown, after the family, from 1620 to 1899.

With his three brothers, Parsons was educated at home in Ireland by private tutors,[1] all of whom were well versed in the sciences and also acted as practical assistants to the Earl in his astronomical work. One of them later became, as Sir Robert Ball, Astronomer Royal for Ireland. Parsons then read mathematics at Trinity College, Dublin and St. John's College, Cambridge, graduating from the latter in 1877 with a first-class honours degree.[6] He joined the Newcastle-based engineering firm of W.G. Armstrong as an apprentice, an unusual step for the son of an earl; then moved to Kitsons in Leeds where he worked on rocket-powered torpedoes; and then in 1884 moved to Clarke, Chapman and Co., ship engine manufacturers near Newcastle, where he was head of their electrical equipment development. He developed a turbine engine there in 1884 and immediately utilized the new engine to drive an electrical generator, which he also designed. Parsons' steam turbine made cheap and plentiful electricity possible and revolutionised marine transport and naval warfare.[7]

Another type of steam turbine at the time, invented by Gustaf de Laval, was an impulse design that subjected the mechanism to huge centrifugal forces and so had limited output due to the weakness of the materials available. Parsons explained that his appreciation of the scaling issue led to his 1884 breakthrough on the compound steam turbine in his 1911 Rede Lecture:

"It seemed to me that moderate surface velocities and speeds of rotation were essential if the turbine motor was to receive general acceptance as a prime mover. I therefore decided to split up the fall in pressure of the steam into small fractional expansions over a large number of turbines in series, so that the velocity of the steam nowhere should be great...I was also anxious to avoid the well-known cutting action on metal of steam at high velocity."[8]

In 1889, he founded C. A. Parsons and Company in Newcastle to produce turbo generators to his design.[9] In the same year he set up the Newcastle and District Electric Lighting Company (DisCO). In 1890, DisCo opened Forth Banks Power Station, the first power station in the world to generate electricity using turbo generators.[10] In 1894 he regained certain patent rights from Clarke Chapman. Although his first turbine was only 1.6% efficient and generated a mere 7.5 kilowatts, rapid incremental improvements in a few years led to his first megawatt turbine built in 1899 for a generating plant at Elberfeld, Germany.[8]

Parsons was also interested in marine applications and founded the Parsons Marine Steam Turbine Company in Newcastle. Famously, in June 1897, his turbine-powered yacht, Turbinia, was exhibited moving at speed at Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee Fleet Review off Portsmouth, to demonstrate the great potential of the new technology. The Turbinia moved at 34 knots. The fastest Royal Navy ships using other technologies reached 27 knots. Part of the speed improvement was attributable to the slender hull of the Turbinia.[11]

Within two years, the destroyers HMS Viper and Cobra were launched with Parsons' turbines, soon followed by the first turbine powered passenger ship, Clyde steamer TS King Edward in 1901; the first turbine transatlantic liners RMS Victorian and Virginian in 1905, and the first turbine powered battleship, HMS Dreadnought in 1906, all of which were driven by Parsons' turbine engines.[9] Today, Turbinia is housed in a purpose-built gallery at the Discovery Museum, Newcastle.[12]

He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in June 1898 and received their Rumford Medal in 1902, their Copley Medal in 1928 and delivered their Bakerian Lecture in 1918.[13] He was the president of the British Association for 1916–1919.[14] He was knighted in 1911 and made a member of the Order of Merit in 1927.[15]

The Parsons turbine company survives in the Heaton area of Newcastle and is now part of Siemens, a German conglomerate. Sometimes referred to as Siemens Parsons, the company recently completed a major redevelopment programme, reducing the size of its site by around three quarters and installing the latest manufacturing technology. In 1925 Charles Parsons acquired the Grubb Telescope Company and renamed it Grubb Parsons. That company survived in the Newcastle area until 1985.

Parsons was also known for inventing the Auxetophone, an early compressed air gramophone.[16]

Parsons' ancestral home at Birr Castle in Ireland houses a museum detailing the contribution the Parsons family have made to the fields of science and engineering, with part of the museum given over to marine engineering work of Charles Parsons.

Personal life and death

In 1883 Parsons married Katharine Bethell, the daughter of William F. Bethell. They had two children: Rachel Mary Parsons (b. 1885), and Algernon George Parsons (b. 1886), who was killed in action during World War I in 1918, aged 31.[17]

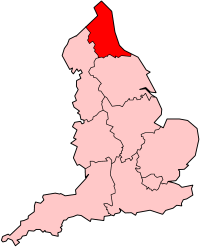

Charles Algernon Parsons died on 11 February 1931, on board the steamship Duchess of Richmond while on a cruise with his wife. The cause of death was given as neuritis.[18] A memorial service was held at Westminster Abbey on 3 March 1931. Parsons was buried in the parish church of St Bartholomew's in Kirkwhelpington in Northumberland.

His widow, Katharine, died at her home in Ray Demesne, Kirkwhelpington, Northumberland in 1933.[19] Rachel Parsons died in 1956; stableman Denis James Pratt was convicted of her manslaughter.[20]

In 1919 Katharine and her daughter co-founded the Women's Engineering Society, which is still in existence today.[21]

Published Works Online and other works of interest

- E-book: "The Steam Turbine and Other Inventions of Sir Charles Parsons"

- The Steam Turbine (Rede Lecture, 1911)

- "From Galaxies to Turbines : Science, Technology and the Parsons Family", by W.G.S.Scaife, Taylor & Francis (1999)

- Charles Parsons' grand-nephew, Michael Parsons in his 1968 Trinity Monday Discourse. http://www.tcd.ie/Secretary/FellowsScholars/discourses/discourses/1968_Lord%20Rosse%20on%20W.%20Parsons.pdf which is in here for the 1968 entry, http://www.tcd.ie/Secretary/FellowsScholars/discourses/

References

- 1 2 http://www.tcd.ie/Secretary/FellowsScholars/discourses/discourses/1968_Lord%20Rosse%20on%20W.%20Parsons.pdf

- ↑ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/444719/Sir-Charles-Algernon-Parsons

- ↑ "Charles Parsons the Person". University of Limerick.

... was an Anglo-Irish engineer,

- ↑ Weightman, Gavin (2011). "Children of Light". Atlantic Books. p. 112. ISBN 0857893009.

Charles Algernon Parsons was from the Anglo-Irish aristocracy

- ↑ Invernizzi, Costante Mario (2013). "Closed Power Cycles". Springer Science & Business Media. p. 1. ISBN 9781447151401.

... Charles Algernon Parsons, 1854–1931, an Anglo-Irish engineer

- ↑ "Parsons, the Hon. Charles Algernon (PRSS873CA)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ↑ http://www.universityscience.ie/pages/scientists/sci_charles_parsons.php

- 1 2 Vaclav Smil (2005), Creating the Twentieth Century: Technical Innovations of 1867-1914 and Their Lasting Impact, Oxford University Press, p. 62, ISBN 0-19-516874-7, retrieved 2009-01-03

- 1 2 Chronology of Charles Parsons, Birr Castle Scientific and Heritage Foundation, archived from the original on 25 December 2008, retrieved 2009-01-03

- ↑ Parsons, R.H. (1939). "X". The Early Days of the Power Station Industry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 171.

- ↑ Charles Algernon Parsons, University of Cambridge Department of Engineering, retrieved 2009-01-03

- ↑ http://www.twmuseums.org.uk/discovery/collections.html

- ↑ "Lists of Royal Society Fellows 1660-2007". London: The Royal Society. Archived from the original on 24 March 2010. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- ↑ Parsons's Presidential Address to the British Science Association Meeting, held at Bournemouth in 1919 (The British Association cancelled its prospective meetings for 1917 and 1918.)

- ↑ http://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/onlinestuff/people/charles%20algernon%20parsons.aspx

- ↑ Reiss, Eric (2007). The compleat talking machine: a collector's guide to antique phonographs. Chandler, Ariz: Sonoran Pub. p. 217. ISBN 1886606226.

- ↑ "Katherine Bethell". The Peerage. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ↑ "Sir Charles Parsons and Sir Arthurt Dorman". Obituaries. The Times (45746). London. 13 February 1931. col B, p. 14.

- ↑ "Obituary The Hon. Lady Parsons". Heaton Works Journal. Women's Engineering Society. December 1933. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ↑ "A history of General Motors in pictures". The Telegraph. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ↑ Heald, Henrietta (23 May 2014). "What was a girl to do? Rachel Parsons (1885–1956): engineer and feminist campaigner". blue-stocking. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

In January 1919, Rachel and her mother, Katharine, established the Women’s Engineering Society, with Rachel as the first president and Caroline Haslett, an electrical engineer, as secretary.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles Algernon Parsons. |

- Chronology of Charles Parsons' Life

- Profile at Cambridge University

- "Parsons and Turbinia". Archived from the original on 10 October 2012.

- Sir Charles Parsons Symposium, excerpts from Transactions of the Newcomen Society