Characene

Characene, (Χαρακηνή in Ancient Greek) also known as Mesene (Μεσσήνη) [1] and Meshan,[2][3] was a kingdom within the Parthian Empire at the head of the Persian Gulf in southern Iraq.[4] Characene's capital was Charax Spasinou (Χάραξ Σπασινού). The city was an important port for trade between Mesopotamia and India, and it provided port facilities for the great city of Susa further up to the present-day Karun River.

Location

Alternatively known as "Mesene" and "Meshan," the kingdom of Characene was located primarily within southern Iraq as part of the Sassanid Empire.[5] At one point, Characene included Tylos, the present-day country of Bahrain.

History

Characene was founded around 127 BC under Aspasine, who was known in classical writings as Hyspaosines, formerly a satrap installed by Antiochus IV Epiphanes. Characene remained intact through the evanescence of the Seleucid Empire and continued as an essentially independent kingdom under the Parthians until it was conquered by the Sassanians in the beginning of the third century AD.

After the Parthian conquest, it remained a semi-autonomous country with its own kings but later disappeared as a separate kingdom when the Parthian Empire fell.

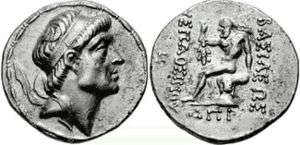

The kings of Characene are mainly known by their coins, consisting mainly of silver tetradrachms with Greek and later Aramaic inscriptions. These coins are dated following the Seleucid era, providing a secure framework for the chronological succession of the kings.

Charax was the capital of Characene that was founded by Alexander the Great. The city was constructed on an artificial mound to protect the site from the flood waters of the nearby rivers. The new town was most likely meant to serve as a major commercial port for the eastern capital of Babylon, a port which would handle sea trade. Charax flourished under the Seleucid Empire, controlling the trade in the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean. It was also a center for pearl diving.

The Roman emperor Trajan visited Charax in 116 AD during his invasion of Parthia and witnessed the ships sailing to India. Trajan reportedly lamented his lost youth, as his old age prevented him from traveling to India like Alexander had.

After being destroyed by a river inundation, Charax was later rebuilt by the Seleucid king Antiochus III the Great (222-187 BC) and was briefly called Antiochia. After the Parthian invasion of Mesopotamia in 141 AD, Charax became independent.

The little state kept its independence (perhaps as a vassal of the Parthian Empire) and sometimes joined the Romans in their struggle against the common enemy, the Parthian king. In his Natural History, Pliny the Elder praises the port of Charax:

- The embankments extend in length a distance of nearly 4½ kilometers, in breadth a little less. It stood at first at a distance of 1¾ km from the shore, and even had a harbor of its own. But according to Juba, it is 75 kilometer from the sea; and at the present day, the ambassadors from Arabia, and our own merchants who have visited the place, say that it stands at a distance of one 180 kilometers from the sea-shore. Indeed, in no part of the world have alluvial deposits been formed more rapidly by the rivers, and to a greater extent than here; and it is only a matter of surprise that the tides, which run to a considerable distance beyond this city, do not carry them back again.[6]

Trade continued to be important for the kingdom. A famous Characenian, a man named Isidore, was the author of a treatise on the trade routes in the Parthian Empire, the Mansiones Parthicae. The inhabitants of Palmyra had a permanent trading station in Characene and many inscriptions mention caravan trade.

In 221-22 AD, an ethnic Persian, Ardašēr, who was satrap of Fars, led a revolt against the Parthians, establishing the Sassanid Empire. According to later Arab histories, he defeated Characene forces, killed its last ruler, rebuilt the town, and renamed it Astarābād-Ardašīr.[7] The area around Charax that had been the Characene state, was thereon known by the Aramaic/Syriac name, Maysān, which was later adapted by the Arab conquerors.[8]

Charax continued, under the name Maysan, with Persian texts making various mention of governors throughout the fifth century. There is mention of a Nestorian Church there in the sixth century. The Charax mint appears to have continued throughout the Sassanid empire time and into the Umayyad empire, minting coins as late as AD 715.[9]

The earliest references from the first century A.D. indicates that the people of Characene were referred to as Μεσηνός and lived along the Arabian side of the coast at the head of the Persian Gulf.

Kings of Characene

- Hyspaosines c. 127–124 BC

- Apodakos c. 110/09–104/03 BC

- Tiraios I 95/94–90/89 BC

- Tiraios II 79/78–49/48 BC

- Artabazos I 49/48–48/47 BC

- Attambelos I 47/46–25/24 BC

- Theonesios I c. 19/18

- Attambelos II c. 17/16 BC – AD 8/9

- Abinergaos I 10/11; 22/23

- Orabazes I c. 19

- Attambelos III c. 37/38–44/45

- Theonesios II c. 46/47

- Theonesios III c. 52/53

- Attambelos IV 54/55–64/65

- Attambelos V 64/65–73/74

- Orabazes II c. 73–80

- Pakoros (II) 80–101/02

- Attambelos VI c. 101/02–105/06

- Theonesios IV c. 110/11–112/113

- Attambelos VII 113/14–117

- Meredates c. 131–150/51

- Orabazes II c. 150/51–165

- Abinergaios II (?) c. 165–180

- Attambelos VIII c. 180–195

- Maga (?) c. 195–210

- Abinergaos III c. 210–222

References

- ↑ Morony, Michael G. (2005). Iraq After The Muslim Conquest. Gorgias Press LLC. p. 155. ISBN 9781593333157.

- ↑ Avner Falk (1996). A Psychoanalytic History of the Jews. p. 330.

In 224 he defeated the Parthian army of Ardavan Shah (Artabanus V), taking Isfahan, Kerman, Elam (Elymais) and Meshan (Mesene, Spasinu Charax, or Characene).

- ↑ Abraham Cohen (1980). Ancient Jewish Proverbs.

The large and small measures roll down and reach Sheol; from Sheol they proceed to Tadmor (Palmyra, Παλμύρα), from Tadmor to Meshan (Mesene), and from Meshan to Harpanya (Hipparenum, Ιππάρενον).

- ↑ Kaveh Farrokh (2007). Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War. p. 124.

With Babylon and Seleucia secured, Mehrdad turned to Charax in southern Mesopotamia (modern south Iraq and Kuwait).

- ↑ Bennett D. Hill; Roger B. Beck; Clare Haru Crowston (2008). A History of World Societies, Combined Volume (PDF). p. 165.

Centered in the fertile Tigris- Euphrates Valley, but with access to the Persian Gulf and extending south to Meshan (modern Kuwait), the Sassanid Empire's economic prosperity rested on agriculture; its location also proved well suited for commerce.

- ↑ Pliny the Elder (AD 77). Natural History. Book VI. xxxi. 138-140. Translation by W. H. S. Jones, Loeb Classical Library, London/Cambridge, Mass. (1961).

- ↑ Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari, Ṭabarī I

- ↑ Yāqūt, Kitab mu'jam al-buldan IV and III

- ↑ Characene and Charax, Characene and Charax Encyclopaedia Iranica

Further reading

- Schuol, Monika (2000) Die Charakene : ein mesopotamisches Königreich in hellenistisch-parthischer Zeit. Stuttgart: F. Steiner. ISBN 3-515-07709-X

- Sheldon A. Nodelman, A Preliminary History of Charakene, Berytus 13 (1959/60), 83-121, XXVII f.,

- Hansman, John (1991) Characene and Charax Encyclopedia Iranica (print version Vol. V, Fasc. 4, pp. 363–365). Retrieved 25 April 2016.