Changeling

A changeling is a creature found in folklore and folk religion. A changeling child was believed to be a fairy child that had been left in place of a human child stolen by the fairies. The theme of the swapped child is common in medieval literature and reflects concern over infants thought to be afflicted with unexplained diseases, disorders, or developmental disabilities.

Description

It is typically described as being the offspring of a fairy, elf or other legendary creature that has been secretly left in the place of a human child. Sometimes the term is also used to refer to the child who was taken. The apparent changeling could also be a stock or fetch, an enchanted piece of wood that would soon appear to grow sick and die. The theme of the swapped child is common among medieval literature and reflects concern over infants thought to be afflicted with unexplained diseases, disorders, or developmental disabilities.

A human child might be taken due to many factors: to act as a servant, the love of a human child, or malice.[1] Most often it was thought that fairies exchanged the children. In rare cases, the very elderly of the Fairy people would be exchanged in the place of a human baby, and then the old fairy could live in comfort, being coddled by its human parents.[2] Simple charms, such as an inverted coat or open iron scissors left where the child sleeps, were thought to ward them off; other measures included a constant watch over the child.[3]

D. L. Ashliman points out that changeling tales illustrate an aspect of family survival in pre-industrial Europe. A peasant family's subsistence frequently depended upon the productive labor of each member, and it was difficult to provide for a person who was a permanent drain on the family's scarce resources. "The fact that the changelings' ravenous appetite is so frequently mentioned indicates that the parents of these unfortunate children saw in their continuing existence a threat to the sustenance of the entire family. Changeling tales support other historical evidence in suggesting that infanticide was not infrequently the solution selected."[3]

Purpose of a changeling

One belief is that trolls thought that it was more respectable to be raised by humans and that they wanted to give their own children a human upbringing. Some people believed that trolls would take unbaptized children. Once children had been baptized and therefore become part of the Church, the trolls could not take them.

Beauty in human children and young women, particularly blond hair, was said to attract the fairies.[4]

In Scottish folklore, the children might be replacements for fairy children in the tithe to Hell;[5] this is best known from the ballad of Tam Lin.[6] According to common Scottish myths, a child born with a caul (head helmet) across his /her face is a changeling, and of fey birth.

Other folklore[2] say that human milk is necessary for fairy children to survive. In these cases either the newborn human child would be switched with a fairy baby to be suckled by the human mother, or the human mother would be taken back to the fairy world to breastfeed the fairy babies. It is also thought that human midwives were necessary to bring fairy babies into the world.

Some stories tell of changelings who forget they are not human and proceed to live a human life. Changelings which do not forget, however, in some stories return to their fairy family, possibly leaving the human family without warning. The human child that was taken may often stay with the fairy family forever.

Some folklorists believe that fairies were memories of inhabitants of various regions in Europe who had been driven into hiding by invaders. They held that changelings had actually occurred; the hiding people would exchange their own sickly children for the healthy children of the invaders.[7]

Changelings in folklore

Cornwall

The Mên-an-Tol stones in Cornwall are supposed to have a fairy or pixie guardian who can make miraculous cures. In one case a changeling baby was put through the stone in order for the mother to get the real child back. Evil pixies had changed her child and the ancient stones were able to reverse their evil spell.[8]

Germany

In respect of popular superstitions, Martin Luther was a product of his times and believed that a changeling was a child of the devil without a human soul.[3] In Germany, the changeling is known as Wechselbalg,[9] Wechselkind,[10] Kielkropf or Dickkopf (the last both hinting at the huge necks and heads of changelings).[9]

Several methods are known in Germany to identify a changeling and to replace it with the real child:

- confusing the changeling by cooking or brewing in eggshells. This nonsense is forcing the changeling to speak, revealing its true age.[9]

- trying to burn the changeling in the oven[11]

- hitting[11] or whipping[10] the changeling

Sometimes the changeling has to be fed with a woman's milk before replacing the children.[10]

In German folklore, several possible parents are known for changelings. Those are:

- the devil[9]

- a female dwarf[11]

- a water spirit[12]

- a Roggenmuhme/Roggenmutter ("Rye Aunt"/"Rye Mother", a demonic woman living in cornfields and stealing human children)[13]

Ireland

In Ireland, looking at a baby with envy – "over looking the baby" – was dangerous, as it endangered the baby, who was then in the fairies' power.[14] So too was admiring or envying a woman or man dangerous, unless the person added a blessing; the able-bodied and beautiful were in particular danger. Women were especially in danger in liminal states: being a new bride, or a new mother.[15]

Putting a changeling in a fire would cause it to jump up the chimney and return the human child, but at least one tale recounts a mother with a changeling finding that a fairy woman came to her home with the human child, saying the other fairies had done the exchange, and she wanted her own baby.[14] The tale of surprising a changeling into speech – by brewing eggshells – is also told in Ireland, as in Wales.[16]

Belief in changelings endured in parts of Ireland until as late as 1895, when Bridget Cleary was killed by her husband who believed her to be a changeling.

Changelings, in some instances, were regarded not as substituted fairy children but instead old fairies brought to the human world to die.

The modern Irish girl's name, Siofra, means an elvish or changeling child.

The Isle of Man

The Isle of Man had a wide collection of myths and superstitions concerning fairies, and there are numerous folk tales that have been collected concerning supposed changelings. Sophia Morrison, in her "Manx Fairy Tales" (David Nutt, London, 1911) includes the tale of "The Fairy Child of Close ny Lheiy", a tale of a child supposedly swapped by the fairies for a loud and unruly fairy child. The English poet and topographer George Waldron, who lived in the Isle of Man during the early 18th century, cites a tale of a reputed changeling that was shown to him, possibly a child with an inherited genetic disorder :

"Nothing under heaven could have a more beautiful face; but though between five and six years old, and seemingly healthy, he was so far from being able to walk, or stand, that he could not so much as move any one joint; his limbs were vastly long for his age, but smaller than an infant's of six months; his complexion was perfectly delicate, and he had the finest hair in the world; he never spoke, nor cried, eat scarce anything, and was very seldom seen to smile, but if any one called him a fairy-elf, he would frown and fix his eyes so earnestly on those who said it, as if he would look them through. His mother, or at least his supposed mother, being very poor, frequently went out a-charing, and left him a whole day together. The neighbours, out of curiosity, have often looked in at the window to see how he behaved when alone, which, whenever they did, they were sure to find him laughing and in the utmost delight. This made them judge that he was not without company more pleasing to him than any mortal's could be; and what made this conjecture seem the more reasonable was, that if he were left ever so dirty, the woman at her return saw him with a clean face, and his hair combed with the utmost exactness and nicety."

Lowland Scotland and Northern England

In the Anglo-Scottish border region it was believed that elves (or fairies) lived in "Elf Hills" (or "Fairy Hills"). Along with this belief in supernatural beings was the view that they could spirit away children, and even adults, and take them back to their own world (see Elfhame).[17][18] Often, it was thought, a baby would be snatched and replaced with a simulation of the baby, usually a male adult elf, to be suckled by the mother.[17] The real baby would be treated well by the elves and would grow up to be one of them, where as the changeling baby would be discontented and wearisome.[18] Many herbs, salves and seeds could be used for discovering the fairy-folk and ward off their designs.[18]

In one tale a mother suspected that her baby had been taken and replaced with a changeling, a view that was proven to be correct one day when a neighbour ran into the house shouting "Come here and ye'll se a sight! Yonder's the Fairy Hill a' alowe." To which the elf got up saying "Waes me! What'll come o' me wife and bairns?" and made his way out of the chimney.[17]

At Byerholm near Newcastleton in Liddesdale sometime during the early 19th century, a dwarf called Robert Elliot or Little Hobbie o' The Castleton as he was known, was reputed to be a changeling. When taunted by other boys he would not hesitate to draw his gully (a large knife) and dispatch them, however being that he was woefully short in the legs they usually out-ran him and escaped. He was courageous however and when he heard that his neighbour, the six-foot three-inch (191 cm) William Scott of Kirndean, a sturdy and strong borderer, had slandered his name, he invited the man to his house, took him up the stairs and challenged him to a duel. Scott beat a hasty retreat.[18]

Child ballad 40, The Queen of Elfan's Nourice, depicts the abduction of a new mother, drawing on the folklore of the changelings. Although it is fragmentary, it contains the mother's grief and the Queen of Elfland's promise to return her to her own child if she will nurse the queen's child until it can walk.[19]

Poland

The Slavic spirit that exchanges the babies (making them into odmieńce) in the cradle is Mamuna or Boginki.[20]

Scandinavia

Since most beings from Scandinavian folklore are said to be afraid of iron, Scandinavian parents often placed an iron item such as a pair of scissors or a knife on top of an unbaptized infant's cradle. It was believed that if a human child was taken in spite of such measures, the parents could force the return of the child by treating the changeling cruelly, using methods such as whipping or even inserting it in a heated oven. In at least one case, a woman was taken to court for having killed her child in an oven.[21]

In one Swedish changeling tale,[22] the human mother is advised to brutalize the changeling so that the trolls will return her son, but she refuses, unable to mistreat an innocent child despite knowing its nature. When her husband demands she abandon the changeling, she refuses, and he leaves her – whereupon he meets their son in the forest, wandering free. The son explains that since his mother had never been cruel to the changeling, so the troll mother had never been cruel to him, and when she sacrificed what was dearest to her, her husband, they had realized they had no power over her and released him.

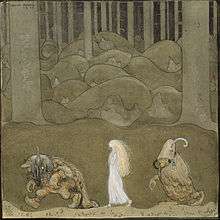

The tale is notably retold by Helena Nyblom as Bortbytingarna[23] in the 1913 book Bland tomtar och troll.[24] (which is depicted by the image), a princess is kidnapped by trolls and replaced with their own offspring against the wishes of the troll mother. The changelings grow up with their new parents, but both find it hard to adapt: the human girl is disgusted by her future bridegroom, a troll prince, whereas the troll girl is bored by her life and by her dull human future groom. Upset with the conditions of their lives, they both go astray in the forest, passing each other without noticing it. The princess comes to the castle whereupon the queen immediately recognizes her, and the troll girl finds a troll woman who is cursing loudly as she works. The troll girl bursts out that the troll woman is much more fun than any other person she has ever seen, and her mother happily sees that her true daughter has returned. Both the human girl and the troll girl marry happily the very same day.

Spain

In Asturias (North Spain) there is a legend about the Xana, a sort of nymph who used to live near rivers, fountains and lakes, sometimes helping travellers on their journeys. The Xanas were conceived as little female fairies with supernatural beauty. They could deliver babies, "xaninos," that were sometimes swapped with human babies in order to be baptized. The legend says that in order to distinguish a "xanino" from a human baby, some pots and egg shells should be put close to the fireplace; a xanino would say: "I was born one hundred years ago, and since then I have not seen so many egg shells near the fire!".

Wales

In Wales the changeling child (plentyn cael (sing.), plant cael (pl.)) initially resembles the human it substitutes, but gradually grows uglier in appearance and behaviour: ill-featured, malformed, ill-tempered, given to screaming and biting. It may be of less than usual intelligence, but again is identified by its more than childlike wisdom and cunning.

The common means employed to identify a changeling is to cook a family meal in an eggshell. The child will exclaim, "I have seen the acorn before the oak, but I never saw the likes of this," and vanish, only to be replaced by the original human child. Alternatively, or following this identification, it is supposedly necessary to mistreat the child by placing it in a hot oven, by holding it in a shovel over a hot fire, or by bathing it in a solution of foxglove.[25]

Changelings in the historical record

Children were thought taken to be changelings by the superstitious, and therefore abused or murdered.

Two 19th century cases reflected the belief in changelings. In 1826, Anne Roche bathed Michael Leahy, a four-year-old boy unable to speak or stand, three times in the Flesk; he drowned the third time. She swore that she was merely attempting to drive the fairy out of him, and the jury acquitted her of murder.[26]

In the 1890s in Ireland, Bridget Cleary was killed by several people, including her husband and cousins, after a short bout of illness (probably pneumonia). Local storyteller Jack Dunne accused Bridget of being a fairy changeling. It is debatable whether her husband, Michael, actually believed her to be a fairy – many believe he concocted a "fairy defence" after he murdered his wife in a fit of rage. The killers were convicted of manslaughter rather than murder, as even after the death they claimed that they were convinced they had killed a changeling, not Bridget Cleary.[27]

Changelings in other countries

The ogbanje (pronounced similar to "oh-BWAN-jeh") is a term meaning "child who comes and goes" among the Igbo people of eastern Nigeria. When a woman would have numerous children either stillborn or die early in infancy, the traditional belief was that it was a malicious spirit that was being reincarnated over and over again to torment the afflicted mother. One of the most commonly prescribed methods for ridding one's self of an ogbanje was to find its iyi-uwa, a buried object that ties the evil spirit to the mortal world, and destroy it. An "abiku" was a rough analogue to the ogbanje among the related Yoruba peoples to the west of Igboland.

Many scholars now believe that ogbanje stories were attempting to explain children with sickle-cell anemia, which is endemic to West Africa and afflicts around one-quarter of the population. Even today, and especially in areas of Africa lacking medical resources, infant death is common for children born with severe sickle-cell anemia.

The similarity between the European changeling and the Igbo ogbanje is striking enough that Igbos themselves often translate the word into English as "changeling".

Aswangs, a kind of ghoul from Filipino folklore, are also sometimes said to leave behind duplicates of their victims made of plant matter. Like the stocks of European fairy folklore, the Aswang's plant duplicates soon appear to sicken and die.

Changelings in the modern world

Neurological differences

The reality behind many changeling legends was often the birth of deformed or developmentally disabled children. Among the diseases or disabilities with symptoms that match the description of changelings in various legends are spina bifida, cystic fibrosis, PKU, progeria, Down syndrome, homocystinuria, Williams syndrome, Hurler syndrome, Hunter syndrome, regressive autism, Prader-Willi Syndrome, and cerebral palsy. The greater proneness of boys with birth defect correlates to the belief that male infants were more likely to be taken.[28]

As noted, it has been hypothesized that the changeling legend may have developed, or at least been used, to explain the peculiarities of children who did not develop normally, probably including all sorts of developmental delays and abnormalities. In particular, it has been suggested that children with autism would be likely to be labeled as changelings or elf-children due to their strange, sometimes inexplicable behavior. For example, this association might explain why fairies are often described as having an obsessive impulse to count things like handfuls of spilled seeds. This has found a place in autistic culture. Some autistic adults have come to identify with changelings (or other replacements, such as aliens) for this reason and their own feeling of being in a world where they do not belong and of practically not being the same species as the other people around them.[29] (Compare the pseudoscientific New Age concept of indigo children.)

In nature

Parasitic cuckoo birds regularly practice brood parasitism, or non-reciprocal offspring-swapping. Rather than raising their young on their own, they will lay their egg in another's nest, leaving the burden on the unsuspecting parents which are of another species altogether. More often than not, the cuckoo chick hatches sooner than its "stepsiblings" and grows faster, eventually hogging most nourishment brought in and may actually "evict" the young of the host species by pushing them off their own nest.

Popular culture

In music:

"The Changeling" is the first song on the album L.A. Woman by The Doors.

Heather Dale's song "Changeling Child" tells the tale of a childless woman who, desperate to have a baby of her own, begs one of the fairies. She gets her wish, but in a sad twist finds the fairies granted her wish literally—they gave her a baby, and a baby the child will forever remain.

In television:

In Supernatural, the Winchesters have faced changelings posing as real children.

In the My Little Pony: Friendship Is Magic, the cast have faced and befriened a changeling.

In literature:

Changelings play a major role in Foxglove Summer, the fifth novel in the Rivers of London series by Ben Aaronovitch. As with various other aspects of magic and myth featured in these book, the phenomenon of fairies kidnapping human children and replacing them with changelings is depicted as quite real and actual event taking place in the present 21st Century reality.

Changelings also play a role in the award winning novel, "Cuckoo Song" where the main character is believed to be a changeling and is thrown into the fire.

Keith Donohue's novel "The Stolen Child" is about a group of changelings who live in a forest in western Pennsylvania.

In film:

In 1980, The Changeling was released, featuring the story of a man who took on the identity of a murdered boy and the man who discovers this when he begins living in the house where the murder took place.

Angelina Jolie starred in Changeling (2008), in which she portrays a mother whose son is kidnapped and replaced with another boy.

In games:

In Magic: The Gathering, the term is used to define a creature that has every single creature type within the game. It also has a card named Crib Swap, which reflects the switcheroo aspect.

Both the original and rebooted World of Darkness settings by White Wolf Games included one game line titled focused on changelings: Changeling: The Dreaming in the original World of Darkness, and Changeling: The Lost in the New World of Darkness. In both games, player characters were changelings, though the approaches differed between the two games: in the first, characters were fae souls reborn into human bodies, a practice begun by the fae to protect themselves as magic vanished from the world. The latter game focused on the folklore concerning mortals kidnapped by faeries and subsequently returned to the mortal world.

In StarCraft II: Wings of Liberty, the changeling is a zerg spy produced by the overseer. The Changeling spawns as a Zerg-looking unit, but upon seeing an enemy unit or building it will automatically transform into the basic unit of that enemy's race. Once disguised, the Changeling takes on the enemy's own color and will no longer be automatically attacked by the enemy's units, allowing it to infiltrate enemy territory unsuspected.[30]

See also

References

- ↑ Katharine Briggs, An Encyclopedia of Fairies, Hobgoblins, Brownies, Boogies, and Other Supernatural Creatures "Changelings" (Pantheon Books, 1976) p. 71. ISBN 0-394-73467-X

- 1 2 Briggs (1979)

- 1 2 3 Ashliman, D. L., "Changelings", 1997. Frenken shows historical pictures of the topic (newborn and the devil): Frenken, Ralph, 2011, Gefesselte Kinder: Geschichte und Psychologie des Wickelns. Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Bachmann. Badenweiler. p. 146, 218 f, 266, 293.

- ↑ Briggs (1976) "Golden Hair", p. 194

- ↑ Silver (1999) p. 74

- ↑ Francis James Child, ballad 39a "Tam Lin", The English and Scottish Popular Ballads

- ↑ Silver (1999) p. 73

- ↑ Wentz, W. Y. Evans (1911). The Fairy-Faith in Celtic Countries. Reprinted 1981. Pub. Colin Smythe. ISBN 0-901072-51-6 P. 179.

- 1 2 3 4 Jacob Grimm: Deutsche Mythologie. Wiesbaden 2007, p. 364.

- 1 2 3 Jacob Grimm: Deutsche Mythologie. Wiesbaden 2007, p. 1039.

- 1 2 3 Ludwig Bechstein: Deutsches Sagenbuch. Meersburg, Leipzig 1930, p. 142 f.

- ↑ Jacob Grimm, Wilhelm Grimm: Deutsche Sagen. Hamburg 2014, p. 126 f.

- ↑ Jacob Grimm, Wilhelm Grimm: Deutsche Sagen. Hamburg 2014, p. 134 f.

- 1 2 W. B. Yeats, Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, in A Treasury of Irish Myth, Legend, and Folklore (1986), p. 47, New York : Gramercy Books, ISBN 0-517-48904-X

- ↑ Silver (1999) p. 167

- ↑ Yeats (1986) p. 48-50

- 1 2 3 Folklore of Northumbria by Fran and Geoff Doel, The History Press, 2009, ISBN 978-0-7524-4890-9. Pages. 17–27.

- 1 2 3 4 The Borderer's Table Book: Or, Gatherings of the Local History and Romance of the English and Scottish Border by Moses Aaron Richardson, Printed for the author, 1846. Page.133-134.

- ↑ Francis James Child, The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, v 1, p 358-9, Dover Publications, New York 1965

- ↑ "Wielka Księga Demonów Polskich. Leksykon i antologia demonologii ludowej". Lubimyczytać.pl. Retrieved 2016-02-08.

- ↑ Klintberg, Bengt af; Svenska Folksägner (1939) ISBN 91-7297-581-4

- ↑ The tale is notably retold by Selma Lagerlöf as Bortbytingen in her 1915 book Troll och människor.

- ↑ http://hem.passagen.se/kurtglim/del1i/

- ↑ http://www.johnbauersmuseum.nu/visa_saga.php?saga=5

- ↑ Wirt Sikes. British Goblins: The Realm of Faerie. Felinfach: Llanerch, 1991.

- ↑ Silver (1999) p. 62

- ↑ Silver (1999) p. 64-65

- ↑ Silver (1999) p. 75

- ↑ Duff, Kim. "The Role of Changeling Lore in Autistic Culture". Presentation at the 1999 Autreat conference of Autism Network International.

- ↑ "Changeling (Legacy of the Void) - Liquipedia - The StarCraft II Encyclopedia". wiki.teamliquid.net. Retrieved 2016-10-27.

External links

"Changeling". Encyclopædia Britannica. 5 (11th ed.). 1911.

"Changeling". Encyclopædia Britannica. 5 (11th ed.). 1911.- D. L. Ashliman's Changelings page at University of Pittsburgh

- ani.ac