Chalcatzingo

Chalcatzingo is a Mesoamerican archaeological site in the Valley of Morelos dating from the Formative Period of Mesoamerican chronology. The site is well known for its extensive array of Olmec-style monumental art and iconography. Located in the southern portion of the Central Highlands of Mexico, Chalcatzingo is estimated to have been settled as early as 1500 BCE. The inhabitants began to produce and display Olmec-style art and architecture around 900 BCE.[1] At its height between 700 BCE and 500 BCE, Chalcatzingo's population is estimated at between five hundred and a thousand individuals. By 500 BCE it had gone into decline.

The Chalcatzingo center covers roughly 100 acres (0.40 km2). It was well-situated in a fertile plain, at the base of two tall hills, Cerro Chalcatzingo and Cerro Delgado. Cerro Chalcatzingo has evidence of long regard and use as a site of ritual significance.[2]

The climate in Morelos is generally warmer and more humid than the rest of the Highlands. A spring rising at the base of the hills provided a source of drinking water for the population.

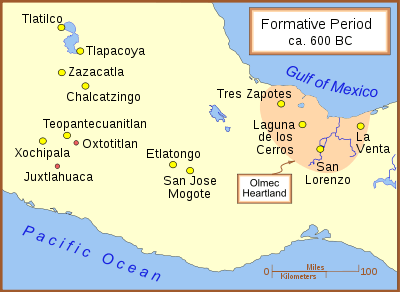

Chalcatzingo connected trade routes between Guerrero, the Valley of Mexico, Oaxaca, and the Gulf Lowlands.

Monuments and carvings

Chalcatzingo provides unique and interesting examples of Olmec-style art and architecture.

The village contained a central plaza area, designated Terrace 1, downhill from elite residences. Terrace 25 is composed of a sunken patio of a style seen at Teopantecuanitlan.

Stone-faced patios and bas-relief monumental art are the features that are found both at Chalcatzingo and at Teopantecuanitlan. These are the only two sites known with these features. The sunken patio of Teopantecuanitlan is older. There are also other parallels between these sites.[3]

At Chalcatzingo, in the center of the sunken patio is a tabletop altar reminiscent of those at La Venta and San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán, both lowland Olmec centers.

Structure 4 is Chalcatzingo’s largest structure, an almost-square platform measuring approximately 70 m (230 ft) on each side. Burials of high-status individuals have been excavated here, with jade ornaments and a magnetite (iron ore) mirror. Most of the village's burials were located under the floors of houses—individuals representing the whole variety of social statuses were buried this way.

Chalcatzingo is perhaps most famous for its bas-relief carvings. Most of the 31 known monuments occur in three distinct groupings: two on Cerro Chalcatzingo and the third on the terraces within the actual settlement.

Drawings of these carvings have been made, but molds were taken of many of them before any drawings were taken. The process of making those molds tended to destroy fine lines and actually tore small portions of the stone out.

Monument 1 (El Rey) and the "Water Dancing Group"

The first group of reliefs lies high on the hillside of Cerro Chalcatzingo. Their apparent common theme of rain and fertility has led Kent Reilly to name this the Water Dancing Group.[4]

This group is dominated by the best known carving from Chalcatzingo: Monument 1, also known as "El Rey" (The King). "El Rey" is a life-size carving of a human-like figure seated inside a cave with a wide opening; the shape of the opening represents one-half of a quatrefoil. The point of view is from the side, and the entire cave appears cross-sectional, with the cave entrance is seen to the right of the figure. The cave entrance is as tall as the figure, and scroll volutes (perhaps indicating speech or perhaps wind) are issuing from it. The cave in which the figure sits is equipped with an eye, and its general shape could suggest that of a mouth.

Above the cave are a number of stylized objects which have been interpreted as rain clouds, with exclamation-like objects ("!") appearing to fall from them. These have been generally interpreted as raindrops.[5]

The seated figure, "El Rey", is dressed ornately. He or she is seated on an elaborate scroll holding another scroll. Since this carving is situated above a major natural water channel that once supplied water to Chalcatzingo, the scene has been interpreted as a leader using his power to bring water to the region. However, "El Rey" has also variously been identified as a rain deity,[6] the "God of the Mountain" - a forerunner of the Aztec's Tepeyollotl,[7] or as the jaguar god who inhabits the caves.

"A striking parallel exists between the imagery of Chalcatzingo Monument 1 and Izapa Stela 8, both of which feature elite individuals enthroned within a quatrefoil."[8]

In addition to "El Rey", the Water Dancing Group includes five smaller bas-reliefs, all depicting various saurian-like creatures sitting atop scrolls[9] underneath exclamation-like objects (again most likely raindrops) falling from what appear to be clouds. These five bas-reliefs—Monuments 5/6, 8, 11, 14, and 15—stretch eastward from Monument 1, separated from it by Cerro Chalcatzingo’s primary natural water channel. These bas-reliefs can only be viewed sequentially, which leads some researchers to suggest that they are likely a pictorial or processional sequence.[10]

The second group

The second group also consists of bas-reliefs, but they have been carved upon the loose stone slabs and boulders at the foot of the mountain rather than on the mountainside. They are larger than those of the Water Dancing group (all but "El Rey") and the carvings primarily depict fantastic creatures dominating outlined human figures:

- Monument 5 depicts a reptilian creature, perhaps the archetypical Mesoamerican feathered serpent, devouring (or, less likely, disgorging) a human. The creature has an elongated snout with large fangs, and triangular markings towards its tail as well as what appear to be fins or wings.

- Monument 4 depicts two humans being attacked by two felines. The human figures are under and slightly in front of the felines, indicating that they may have been fleeing. The felines have their fangs bared and claws extended towards the figures. The felines appear to be wearing various bits of ornamentation, while their eyes show the St Andrew's Cross ("X") motif, suggesting these might be jaguar gods or that these jaguars are affiliated with the sun god.

- Monument 3 depicts a recumbent feline next to a cactus-like plant, with a possible subordinate human figure in a damaged area of the carving.

- Monument 31 depicts a recumbent feline atop a human, perhaps attacking him, although this carving does not possess the sense of motion shown in Monument 4. Three raindrops, like those in El Rey, can be seen falling from above. Interpretations of this scene range from the idea that raindrops falling on the jaguar comprise a fertility metaphor to themes of bloodletting and sacrifice.

According to UIUC archaeologist David Grove, these four reliefs likely illustrate "a sequence of mythical events important in the cosmogony of the peoples of Chalcatzingo".[11]

- Monument 2, at the west end of the series, shows four humans. Three of them are standing while the fourth, on the right, is seated upon the ground, inertly slumped backwards, perhaps bound. All are masked, although the fourth has his mask on the back of his head. The three standing figures are brandishing spears or pikes. The headdress worn by one of the standing figures echoes the motifs adorning the head of one of Monument 4’s felines, suggesting that this scene is related to the events depicted in the others in the sequence.

While these first five occur in a processional arrangement, a sixth carving of this group, labelled Monument 13, is considerably downhill. It depicts a supernatural anthropomorphic being with the cleft head often found in Olmec iconography. Like "El Rey", it is seated within the quatrefoil mouth of what is likely a supernatural creature.

Other carvings

Monument 9

Monument 9 is a sculpture that may represent the cave in Monument 1 from a head-on point of view. The sculpture is flat and contains a large hole in the middle that would correspond to the shape of the cave entrance. This represents the full quatrefoil.[12] Above that hole are two eyes, similar to the eye in Monument 1.

Monument 21

Chalcatzingo contains what may be the earliest representation of a woman in Mesoamerican monumental art on Monument 21. The monument is a stela, originally erected at the front of Terrace 15 during the Cantera phase of occupation (700-500 BCE). The top of the monument is missing. The monument depicts a woman dressed in sandals, head covering, and a skirt who is touching – or perhaps erecting[13] – a bound stela. The woman and the depicted stela rest upon what has been identified as a stylized earth monster.[14]

This image possibly represents a woman with her marriage dowry and appears to be mirrored by Monument 32, which portrays a male touching a stela in a similar, but mirrored, position.[15]

Key highland site

While Chalcatzingo is perhaps best known for its bas-relief carvings, taken to infer an Olmec presence in the prehistoric community, the bulk of the evidence from this site indicates that it was a vibrant presence in the Mexican Central Highlands owing little to any Olmec incursion or contact. The Central Mexican identity can perhaps best be appreciated by contrasting the character of the monumental art with the numerous anthropomorphic figurines recovered at Chalcatzingo. These figurines, which are clearly within an indigenous Central Mexican tradition, may be thought of as depicting the people who lived in Morelos at the dawn of Mesoamerican civilization.[16]

Decline

Like other Formative period culture centers, Chalcatzingo declined in importance but, unlike centers on the Gulf Coast, the site was not abandoned. The location has clear evidence of a minor occupation in the Late Formative Period and served as a minor ceremonial center during the Classic period. However, by 500 BCE Chalcatzingo had lost its centrality in Mexican Highland culture. This occurred some 400 years after San Lorenzo was abandoned, and 100 years before the abandonment of La Venta. Chalcatzingo’s decline coincided with the development of widespread settlement clusters throughout the Morelos region, consisting mainly of small farming villages. Over 1000 years after Chalcatzingo’s abandonment, the Late Classic settlement Xochicalco reached its peak in Morelos between 700–900 CE.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chalcatzingo. |

Notes

- ↑ Grove (1999, p.255)

- ↑ Grove (1999, p.258)

- ↑ Bruce G. Trigger, ed., The Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas. Cambridge University Press, 1996 ISBN 0521351650 p146

- ↑ Reilly, p. 4.

- ↑ See Diehl (2004, p.177).

- ↑ Such as by Gay and Pratt (1971).

- ↑ See annotation by Aguilar (2002).

- ↑ Love, M.; Guernsey, J. (2007). "Monument 3 from La Blanca, Guatemala: A Middle Preclassic earthen sculpture and its ritual associations". Antiquity. 81 (314): 920–932. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00096009.

- ↑ Reilly (1996) refers to these 'scrolls' as "lazy [sideways] S" patterns.

- ↑ Grove (1999, p.260).

- ↑ Grove (1999, p.261).

- ↑ Love, M.; Guernsey, J. (2007). "Monument 3 from La Blanca, Guatemala: A Middle Preclassic earthen sculpture and its ritual associations". Antiquity. 81 (314): 920–932. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00096009.

- ↑ Reilly (2002), p. 49.

- ↑ Reilly (2002), p. 49.

- ↑ Aviles, p. 17.

- ↑ See Harlan (1987, pp.252–263).

References

- Aguilar, Manuel (2002). "Monument 1: Relief of "El Rey" (The King)". Mesoamerican Art. California State University Los Angeles. Retrieved 2006-09-15.

- Aviles, Maria (2000). "The Archaeology of Early Formative Chalcatzingo, Morelos, México, 1995" (PDF). Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc. (FAMSI). Retrieved 2013-05-10.

- Diehl, Richard (2004). The Olmecs: America's First Civilization. Ancient peoples and places series. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-02119-8. OCLC 56746987.

- Evans, Susan Toby (2004). Ancient Mexico & Central America: Archaeology and Culture History. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-28440-7. OCLC 55125990.

- Gay, Carlo T.E.; Frances Pratt (1971). Chalcacingo. Graz, Austria: Akademische Druck-u. Verlagsanstalt. OCLC 333856.

- Grove, David C. (1999). "Public Monuments and Sacred Mountains: Observations on Three Formative Period Sacred Landscapes" (PDF). In David C. Grove and Rosemary A. Joyce (eds.). Social Patterns in Pre-Classic Mesoamerica: A Symposium at Dumbarton Oaks, 9 and 10 October 1993 (Dumbarton Oaks etexts ed.). Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. pp. 255–300. ISBN 0-88402-252-8. OCLC 39229716.

- Harlan, Mark E. (1987). "Chalcatzingo's Formative Figurines" (PDF online facsimile). In David C. Grove (ed.). Ancient Chalcatzingo. Texas Pan American series. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 252–263. ISBN 0-292-70372-4. OCLC 59802706.

- Reilly, F. Kent, III (1991), ""Olmec iconographic influence on the Symbols of Maya rulership: An Examination of Possible Sources" , in Sixth Palenque Round Table, 1986 edited by Merle Greene Robertson and Virginia M. Fields .

- Reilly, F. Kent, III (1996), ""The Lazy-S: A Formative Period Iconographic Loan to Maya Hieroglyphic Writing", in Eighth Palenque Round Table, 1993 edited by Martha J. Macri and Jan McHargue.

- Reilly, F. Kent, III (2002) "The Landscape of Creation: Architecture, Tomb, and Monument Placement at the Olmec Site of La Venta" in Andrea Stone Heart of Creation: the Mesoamerican World and the Legacy of Linda Schele, University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa, Alabama, ISBN 0-8173-1138-6.

External links

- Dr. Manuel Aguilar's notes and photos on Chalcatzingo

- National Institute of Anthropology and History website for Chalcatzingo

- The DeLanges visit Chalcatzingo, with lots of photos

- Photo tour of Chalcatzingo by David R. Hixson. Click on "Chalcatzingo" for photos as well as a site summary by David Grove and Maria Aviles (site archaeologists).

- Ancient Chalcatzingo, facsimile chapters of the 1987 book edited by David Grove, downloadable as PDFs, at FAMSI

- Identity and Diversity in the Anthropomorphic Figurines from Chalcatzingo, Morelos, Mexico

Coordinates: 18°41′N 98°46′W / 18.683°N 98.767°W