Central serous retinopathy

| Central serous retinopathy | |

|---|---|

|

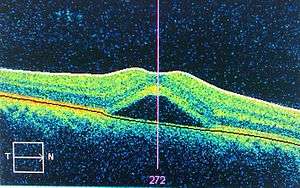

An occurrence of central serous retinopathy of the fovea centralis imaged using Optical coherence tomography. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | ophthalmology |

| ICD-10 | H35.7 |

| ICD-9-CM | 362.41 |

| DiseasesDB | 31277 |

| MedlinePlus | 001612 |

| eMedicine | oph/689 |

Central serous retinopathy (CSR), also known as central serous chorioretinopathy (CSC or CSCR), is an eye disease which causes visual impairment, often temporary, usually in one eye.[1][2] When the disorder is active it is characterized by leakage of fluid under the retina that has a propensity to accumulate under the central macula. This results in blurred or distorted vision (metamorphopsia). A blurred or gray spot in the central visual field is common when the retina is detached. Reduced visual acuity may persist after the fluid has disappeared.[1]

The disease is considered idiopathic but mostly affects white males in the age group 20 to 50 and occasionally other groups. The condition is believed to be exacerbated by stress or corticosteroid use.[3]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis usually starts with a dilated examination of the retina, followed with confirmation by optical coherence tomography and fluorescein angiography. The angiography test will usually show one or more fluorescent spots with fluid leakage. In 10%-15% of the cases these will appear in a "classic" smoke stack shape.

Indocyanine green angiography can be used to assess the health of the retina in the affected area which can be useful in making a treatment decision. An Amsler grid can be useful in documenting the precise area of the visual field involved. The affected eye will sometimes exhibit a refractive spectacle prescription that is more far-sighted than the fellow eye due to the decreased focal length caused by the raising of the retina.

Causes

CSR is a fluid detachment of macula layers from their supporting tissue. This allows choroidal fluid to leak beneath the retina. The build-up of fluid seems to occur because of small breaks in the retinal pigment epithelium.

CSR is sometimes called idiopathic CSR which means that its cause is unknown. Nevertheless, stress appears to play an important role. An oft-cited but potentially inaccurate conclusion is that persons in stressful occupations, such as airplane pilots, have a higher incidence of CSR.

CSR has also been associated with cortisol and corticosteroids. Persons with CSR have higher levels of cortisol.[4] Cortisol is a hormone secreted by the adrenal cortex which allows the body to deal with stress, which may explain the CSR-stress association. There is extensive evidence to the effect that corticosteroids (e.g. cortisone) — commonly used to treat inflammations, allergies, skin conditions and even certain eye conditions — can trigger CSR, aggravate it and cause relapses.[5][6][7] A study of 60 persons with Cushing's syndrome found CSR in 3 (5%).[8] Cushing's syndrome is characterized by very high cortisol levels. Certain sympathomimetic drugs have also been associated with causing the disease.[9]

Evidence has also implicated helicobacter pylori (see gastritis) as playing a role.[10][11][12] It would appear that the presence of the bacteria is well correlated with visual acuity and other retinal findings following an attack.

Evidence also shows that sufferers of MPGN type II kidney disease can develop retinal abnormalities including CSR caused by deposits of the same material that originally damaged the glomerular basement membrane in the kidneys.[13]

Prognosis

The prognosis for CSR is generally excellent.[1] Whilst immediate vision loss may be as poor as 20/200 in the affected eye, clinically over 90% of patients regain 20/30 vision or better within 6 months.

Once the fluid has resolved, by itself or through treatment, visual acuity should continue to improve and distortion should reduce as the eye heals. However, some visual abnormalities can remain even if visual acuity is measured at 20/20, and lasting problems include decreased night vision, reduced color discrimination, and localized distortion caused by scarring of the sub-retinal layers.[14]

Complications include subretinal neovascularization and pigment epithelial detachment.[15]

The disease can re-occur causing progressive vision loss. There is also a chronic form, titled as type II central serous retinopathy, which occurs in approximately 5% of cases. This exhibits diffuse rather than focalized abnormality of the pigment epithelium, producing a persistent subretinal fluid. The serous fluid in these cases tends to be shallow rather than dome shaped. Prognosis for this condition is less favorable and continued clinical consultation is advised.

Treatment

Differential diagnosis should be immediately performed to rule out retinal detachment, which is a medical emergency. Additionally, a clinical record should be taken to keep a timeline of the detachment.

Most eyes with CSR undergo spontaneous resorption of subretinal fluid within 3–4 months, recovery of visual acuity usually follows. Any ongoing corticosteroid treatment should be tapered and stopped, where possible. It is important to check current medication, including nasal sprays and creams, for ingredients of corticosteroids, if found seek advice from a medical practitioner for an alternative.

Patients sometimes present with an obvious history of psychosocial stress, in which case counselling and expectancy is relevant.

Treatment should be considered if resorption does not occur within 3–4 months,[16] spontaneously or as the result of counselling.[1]

Laser photocoagulation, which effectively burns the leak area shut, may be considered in cases where there is little improvement in a 3 to 4-month duration, and the leakage is confined to a single or a few sources of leakage at a safe distance from the fovea. However, for many cases the leak is very near the central macula, where photocoagulation would leave a blind spot or the leakage is widespread and its source is difficult to identify. Foveal attenuation has been associated with more than 4 months' duration of symptoms, however a better long-term outcome has not been demonstrated with laser photocoagulation than without photocoagulation.[1] Laser photocoagulation can permanently damage vision where applied. Carefully tuned lasers can limit this damage.[17] Even so, laser photocoagulation is not a preferred treatment for leaks in the central vision and is considered an outdated treatment by some doctors.[16]

In chronic cases, transpupillary thermotherapy has been suggested as an alternative to laser photocoagulation where the leak is in the central macula.[18]

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) with verteporfin has shown promise as an effective treatment with minimal complications.[19] Follow up studies have confirmed the treatment's long-term effectiveness[20] including its effectiveness for the chronic variant of the disease.[21] Indocyanine green angiography can be used to predict how the patient will respond to PDT.[16][22]

Yellow micropulse laser has shown promise in very limited trials.[3]

Other experimental treatments include anti-VEGFs and several oral medications.[23]

Low dosage ibuprofen has been shown to quicken recovery in some cases, whilst avoiding naturally occurring blood thinners such as garlic, turmeric, cinnamon, which can enhance leakage from capillaries behind the retina.[24]

A Cochrane review seeking to compare the effectiveness of various treatment for CSR found low quality evidence that half-dose PDT treatment resulted in improved visual acuity and less recurrence of CSR in patients with acute CSR, compared to patients in the control group.[25] The review also found benefits in micropulse laser treatments, where patients with acute and chronic CSR had improved visual acuity compared to control patients.[25]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wang, Maria; Munch, Inger Christine; Hasler, Pascal W.; Prünte, Christian; Larsen, Michael (2008). "Central serous chorioretinopathy". Acta Ophthalmologica. 86 (2): 126–45. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0420.2007.00889.x. PMID 17662099.

- ↑ Quillen, DA; Gass, DM; Brod, RD; Gardner, TW; Blankenship, GW; Gottlieb, JL (1996). "Central serous chorioretinopathy in women". Ophthalmology. 103 (1): 72–9. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(96)30730-6. PMID 8628563.

- 1 2 André Maia (February 2010). "A New Treatment for Chronic Central Serous Retinopathy". Retina Today. Retrieved 2013-08-11.

- ↑ Garg, S P; Dada, T.; Talwar, D.; Biswas, N R (1997). "Endogenous cortisol profile in patients with central serous chorioretinopathy". British Journal of Ophthalmology. 81 (11): 962–4. doi:10.1136/bjo.81.11.962. PMC 1722041

. PMID 9505819.

. PMID 9505819. - ↑ Pizzimenti, Joseph J.; Daniel, Karen P. (2005). "Central Serous Chorioretinopathy After Epidural Steroid Injection". Pharmacotherapy. 25 (8): 1141–6. doi:10.1592/phco.2005.25.8.1141. PMID 16207106.

- ↑ Bevis, Timothy; Ratnakaram, Ramakrishna; Smith, M Fran; Bhatti, M Tariq (2005). "Visual loss due to central serous chorioretinopathy during corticosteroid treatment for giant cell arteritis". Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 33 (4): 437–9. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9071.2005.01017.x. PMID 16033370.

- ↑ Fernández Hortelano, A; Sádaba, LM; Heras Mulero, H; García Layana, A (2005). "Coroidopatía serosa central como complicación de epitelitis en tratamiento con corticoides" [Central serous chorioretinopathy as a complication of epitheliopathy under treatment with glucocorticoids]. Archivos de la Sociedad Española de Oftalmología (in Spanish). 80 (4): 255–8. doi:10.4321/S0365-66912005000400010. PMID 15852168.

- ↑ Bouzas, Evrydiki A.; Scott, MH; Mastorakos, G; Chrousos, GP; Kaiser-Kupfer, MI (1993). "Central Serous Chorioretinopathy in Endogenous Hypercortisolism". Archives of Ophthalmology. 111 (9): 1229–33. doi:10.1001/archopht.1993.01090090081024. PMID 8363466.

- ↑ Michael, John C; Pak, John; Pulido, Jose; De Venecia, Guillermo (2003). "Central serous chorioretinopathy associated with administration of sympathomimetic agents". American Journal of Ophthalmology. 136 (1): 182–5. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(03)00076-X. PMID 12834690.

- ↑ Giusti, Cristiano (2004). "Association of Helicobacter pylori with central serous chorioretinopathy: Hypotheses regarding pathogenesis". Medical Hypotheses. 63 (3): 524–7. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2004.02.020. PMID 15288381.

- ↑ Ahnoux-Zabsonre, A.; Quaranta, M.; Mauget-Faÿsse, M. (2004). "Prévalence de l'Helicobacter pylori dans la choriorétinopathie séreuse centrale et l'épithéliopathie rétinienne diffuse" [Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in central serous chorioretinopathy and diffuse retinal epitheliopathy: a complementary study]. Journal Français d'Ophtalmologie (in French). 27 (10): 1129–33. doi:10.1016/S0181-5512(04)96281-X. PMID 15687922.

- ↑ Cotticelli, L; Borrelli, M; d'Alessio, AC; Menzione, M; Villani, A; Piccolo, G; Montella, F; Iovene, MR; Romano, M (2006). "Central serous chorioretinopathy and Helicobacter pylori". European journal of ophthalmology. 16 (2): 274–8. PMID 16703546.

- ↑ Colville, Deb; Guymer, Robyn; Sinclair, Roger A; Savige, Judy (2003). "Visual impairment caused by retinal abnormalities in mesangiocapillary (membranoproliferative) glomerulonephritis type II ('dense deposit disease')". American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 42 (2): E2–5. doi:10.1016/S0272-6386(03)00665-6. PMID 12900843.

- ↑ Baran, Nergis V; Gurlu, Vuslat P; Esgin, Haluk (2005). "Long-term macular function in eyes with central serous chorioretinopathy". Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 33 (4): 369–72. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9071.2005.01027.x. PMID 16033348.

- ↑ Kanyange, ML; De Laey, JJ (2002). "Long-term follow-up of central serous chorioretinopathy (CSCR)". Bulletin de la Societe belge d'ophtalmologie (284): 39–44. PMID 12161989.

- 1 2 3 Boscia, Francesco (April 2010). "When to Treat and Not to Treat Patients With Central Serous Retinopathy". Retina Today.

- ↑ Roider, Johann; Brinkmann, R; Wirbelauer, C; Laqua, H; Birngruber, R (1999). "Retinal Sparing by Selective Retinal Pigment Epithelial Photocoagulation". Archives of Ophthalmology. 117 (8): 1028–34. doi:10.1001/archopht.117.8.1028. PMID 10448745.

- ↑ Wei, SY; Yang, CM (2005). "Transpupillary thermotherapy in the treatment of central serous chorioretinopathy". Ophthalmic surgery, lasers & imaging. 36 (5): 412–5. PMID 16238041.

- ↑ Ober, Michael D.; Yannuzzi, Lawrence A.; Do, Diana V.; Spaide, Richard F.; Bressler, Neil M.; Jampol, Lee M.; Angelilli, Allison; Eandi, Chiara M.; Lyon, Alice T. (2005). "Photodynamic Therapy for Focal Retinal Pigment Epithelial Leaks Secondary to Central Serous Chorioretinopathy". Ophthalmology. 112 (12): 2088–94. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.06.026. PMID 16325707.

- ↑ Chan, Wai-Man; Lai, Timothy Y.Y.; Lai, Ricky Y.K.; Liu, David T.L.; Lam, Dennis S.C. (2008). "Half-Dose Verteporfin Photodynamic Therapy for Acute Central Serous Chorioretinopathy". Ophthalmology. 115 (10): 1756–65. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.04.014. PMID 18538401.

- ↑ Karakus SH, Basarir B, Pinarci EY, Kirandi EU, Demirok A (May 2013). "Long-term results of half-dose photodynamic therapy for chronic central serous chorioretinopathy with contrast sensitivity changes.". Eye. doi:10.1038/eye.2013.24. PMID 23519277.

- ↑ Inoue, Ryo; Sawa, Miki; Tsujikawa, Motokazu; Gomi, Fumi (2010). "Association Between the Efficacy of Photodynamic Therapy and Indocyanine Green Angiography Findings for Central Serous Chorioretinopathy". American Journal of Ophthalmology. 149 (3): 441–6.e1–2. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2009.10.011. PMID 20172070.

- ↑ Caccavale, Antonio; Romanazzi, F; Imparato, M; Negri, A; Morano, A; Ferentini, F (2011). "Central serous chorioretinopathy: A pathogenetic model". Clinical Ophthalmology. 5: 239–43. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S17182. PMC 3046994

. PMID 21386917.

. PMID 21386917. - ↑ Pecora, JL (10 November 1978). "Ibuprofen in the treatment of central serous chorioretinopathy". Ann Ophthalmol. 11: 1481–3. PMID 727624.

- 1 2 Salehi M, Wenick AS, Law HA, Evans JR, Gehlbach P (2015). "Interventions for central serous chorioretinopathy: a network meta-analysis". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 12: CD011841. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011841.pub2. PMID 26691378.