Caulonia (ancient city)

| Καυλωνία | |

|

Ruins of a Doric temple at the site of ancient Caulonia | |

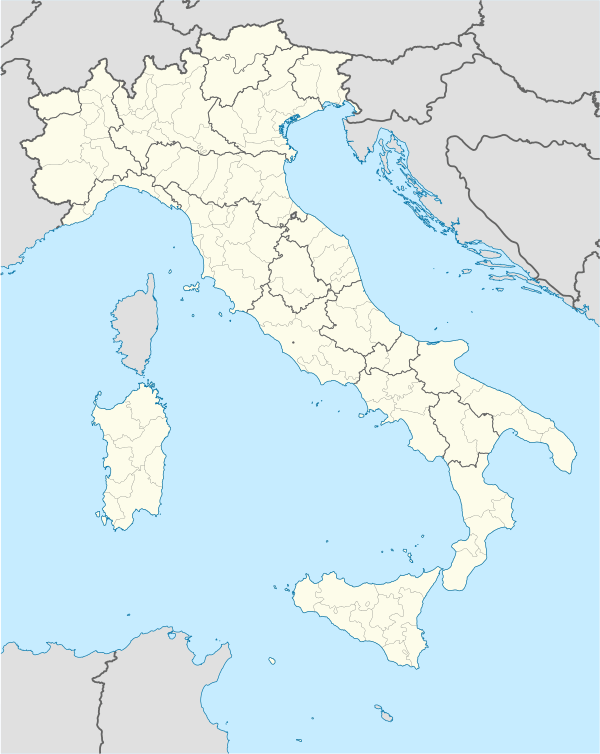

Shown within Italy | |

| Location | Monasterace, Province of Reggio Calabria, Calabria, Italy. |

|---|---|

| Region | Magna Graecia |

| Coordinates | 38°26′44″N 16°34′44″E / 38.44556°N 16.57889°ECoordinates: 38°26′44″N 16°34′44″E / 38.44556°N 16.57889°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| Area | 35–45 ha (110 acres) |

| History | |

| Builder | Settlers from Aegium or Croton |

| Founded | Early second half of 7th century BC |

| Abandoned | Approximately 200 BC |

| Periods | Archaic Greece to Roman Republic |

| Site notes | |

| Management | Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici della Calabria |

| Website | ArcheoCalabriaVirtual (Italian) |

Caulonia or Caulon (Ancient Greek: Καυλωνία Kaulōnía;[1] also spelled Kaulonia or Kaulon) was an ancient city of Magna Graecia on the shore of the Ionian Sea. At some point after the destruction of the city by Rome in 200 BC, the inhabitants moved to a location further inland. There they founded Stilida, which developed into the modern town Stilo.

Since 1863 AD the name Caulonia has also been used by the city formerly known as Castelvetere. The city changed its name to Caulonia in honor of the ancient city, which was mistakenly believed to have been located in its territory.[2] Today the ruins of the ancient city can be found near Monasterace in the Province of Reggio Calabria, Calabria, Italy. Some of the artefacts which have been excavated at the site can now be seen in the Monasterace Archeological Museum.

Geography

The city was located between the mouth of the Stilaro river to the south and the mouth of the Assi river to the north. In ancient times the mouth of the Assi was located slightly further to the south. Punta Stilo, the "Cape of Columns", is a gentle arc-shaped headland located immediately north of the site. In ancient times the shoreline of Caulonia lay 300 meter further seawards. More than one hundred fluted columns which have been discovered on the seabed in front of Caulonia stood then on a broad arc-shaped headland. This headland probably did not have natural or artificial facilities which could provide protected anchorage for ships. The recession of the coastline started around 400 BC and ended in the 1st century AD. It was the result of a tectonic phase which caused landward rise and submergence of the seafloor. The shoreline stabilized in the period from the 1st century AD to the present.[3] The walls of the city enclosed an area of approximately 35 to 45 hectares (110 acres).[4]

History

Foundation

There is no literary evidence for the foundation date of Caulonia, but archeological evidence shows that it was founded early in the second half of the seventh century BC.[5] Both Strabo and Pausanias mention that the city was founded by Achaean Greek colonists. Pausanias also gives the name of the oekist, or founder, as Typhon of Aegium.[6] Others sources such as Pseudo-Scymnus claim that it was founded by Croton.[7] A. J. Graham does not consider these two options to be mutually exclusive because the oekist and settlers could have been invited by Croton.[5]

Sixth and fifth centuries BC

It has been thought that Caulonia was ruled by Croton for some time, but A. J. Graham considers this uncertain. The fact that Caulonia minted its own coins in the sixth century BC suggests that it was independent. Also, the claim of Croton over such a long stretch of coast close to its rival Locri would have been risky.[5] According to Thucydides Caulonia supplied Athens with timber for ships during the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC). The store of timber at Caulonia was attacked and burned by forces from Syracuse.[8]

Destroyed thrice and relocated

In 389 BC the city was conquered by Dionysius I of Syracuse, who transplanted its citizens to Syracuse and gave them citizenship and an exemption from taxes for five years. He then levelled the city to the ground and gave its territory to his ally Locri.[9] Apparently it was refounded by Dionysius II of Syracuse several decades later.[10] Dionysius II probably gave control over the city to Locri. Archaeological evidence confirms that the city was deserted for some time in the fourth century BC.[11]

This was not the end of misfortune for the city however, for it was razed two more times. It was destroyed during the Pyrrhic War (280–275 BC) and taken by the Campanians, who formed the largest contingent of allies in the army of Rome.[12] In 200 BC the town was completely destroyed by the Romans, when it sided with Hannibal during the Punic Wars. It was probably around this time that the ancient site of Caulonia, directly on the Ionian coast, was abandoned in favor of a more protected site inland.[13] About 200 years later when the city is mentioned by Strabo, it is described by him as "situated before a valley" and deserted.[14]

Archaeology

The first archaeological excavations were conducted between 1911 and 1913 by Paolo Orsi.

The excavation area is named "Saggio SAS II" and topologically "San Marco nord-est". It is bordered by the Ionian Sea on the east, the Taranto-Reggio Calabria railway on the west, the Assi river on the north and the "casemate" area on the south.

In 1969 a mosaic depicting a dragon was discovered in what is now called the "House of the Dragon". It was first exhibited in the Museo Nazionale della Magna Grecia, but was restored and transferred to the Monasterace Archeological Museum in 2012.[15]

In 2012 the archaeologist Francesco Cuteri and his team discovered a mosaic floor of 25 square meters. Dating to late 4th century BC, it is one of the largest mosaics from the Hellenistic period found in Southern Italy. It was discovered in what is thought to have been a thermal bathhouse. The mosaic is divided into nine polychrome squares and another space with a polychrome rosette at the entrance of the room. It depicts a dragon in its center, comparable to the mosaic discovered in 1969.[15]

On 8 October 2013 the discovery of a bronze tablet from fifth century BC in the urban sanctuary was announced. The tablet has a dedication of eighteen lines written in the Achaean alphabet, the longest Achaean inscription ever discovered in Magna Graecia.[16]

Gallery

- Ruins of a house

- The large mosaic discovered in 2012

- Detail of the large mosaic

a doric capital (reversed)

a doric capital (reversed)- Several excavated structures

- Excavations at Caulonia in August 2013

Map of the site

Map of the site Silver stater of Caulonia, c. 400–388 BC

Silver stater of Caulonia, c. 400–388 BC

References

- ↑ Muggia 2006.

- ↑ Bova 2008, p. 39.

- ↑ Stanley 2007.

- ↑ Hansen 2004, p. 34.

- 1 2 3 Graham 1982, p. 181.

- ↑ Strabo 1924, 6.1.10; Pausanias 1918, 6.3.12.

- ↑ Pseudo-Scymnus, Periodos to Nicomedes 318–319

- ↑ Thucydides 1843, 7.25.2.

- ↑ Diodorus Siculus 1954, 14.106.3.

- ↑ Diodorus Siculus 1952, 16.10.2, 16.11.3; Plutarch 1918, Dion 26.4.

- ↑ Fronda 2010, p. 170.

- ↑ Pausanias 1918, 6.3.12.

- ↑ Maria Elisa Campisi, Guida Turistica di Caulonia, Rubbettino Industrie Grafiche ed Editoriali, 2008.

- ↑ Strabo 1924, 6.1.10.

- ↑ Caridi 2013; Fame di Sud 2013.

Sources

- Primary sources

- Diodorus Siculus (1952). Sherman, Charles L., ed. Library of History. 7. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-99428-7.

- ——— (1954). Oldfather, C. H., ed. Library of History. 6. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-99439-3.

- Pausanias (1918). Jones, W. H. S., ed. Description of Greece. 3. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-99300-6.

- Plutarch (1918). Perrin, Bernadotte, ed. Lives. 6. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-99109-5.

- Strabo (1924). Jones, H. L., ed. Geography. 3. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-99201-6.

- Thucydides (1843). Thomas, Hobbes, ed. History of the Peloponnesian War. London: Bohn.

- Secondary sources

- Abenavoli, Paola (19 October 2012). "Scoperto a Monasterace il più grande mosaico ellenistico del sud Italia". Il Sole 24 Ore (in Italian). Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- Bova, Damiano (2008). Bivongi nella valle dello Stilaro. Bari: Ecumenica Editrice. ISBN 978-88-8875-843-5.

- Caridi, Peppe (2013). "Straordinaria scoperta archeologica a Kaulonia (RC): ecco il testo più lungo in alfabeto acheo della Magna Grecia" (in Italian). Meteoweb. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- "Ritrovato a Kaulonia, in Calabria, il testo più lungo in alfabeto acheo della Magna Grecia" (in Italian). Fame di Sud. 8 October 2013. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- Fronda, Michael P. (2010). Between Rome and Carthage: Southern Italy During the Second Punic War. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-48862-4.

- Graham, A. J. (1982). "The western Greeks". In Boardman, John; N. G. L., Hammond. The expansion of the Greek world, eight to sixth centuries B.C. The Cambridge Ancient History. 3. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-23447-4.

- Hansen, Mogens Herman (2004). "The Concept of the Consumption City Applied to the Greek Polis". In Nielsen, Thomas Heine. Once Again: Studies in the Ancient Greek Polis. Historia Einzelschriften. 180. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 978-3-515-08438-3.

- Muggia, Anna Pavia (2006). Cancik, Hubert; Schneider, Helmuth, eds. "Caulonia". Brill’s New Pauly. Brill Online. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- Stanley, Jean-Daniel (2007). "Kaulonia, southern Italy: Calabrian Arc tectonics inducing Holocene coastline shifts". Méditerranée (108): 7–15. doi:10.4000/mediterranee.152.

Further reading

- Barello, Federico (1995). Architettura greca a Caulonia. Edilizia monumentale e decorazione architettonica in una città della Magna Grecia (in Italian). Florence: Le Lettere. ISBN 978-88-7166-211-4.

- Lepore, Lucia; Turi, Paola, eds. (2010). Caulonia tra Crotone e Locri. Conference proceedings, Firenze, 30 May–1 June 2007 (in Italian). Florence: Firenze University Press. ISBN 978-88-8453-931-1.

- Parra, Maria Cecilia, ed. (2001). Kaulonia, Caulonia, Stilida (e oltre): Contributi Storici, Archeologici e Topografici (in Italian). 1. Pisa: Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa.

- Parra, Maria Cecilia, ed. (2004). Kaulonia, Caulonia, Stilida (e oltre): Contributi Storici, Archeologici e Topografici (in Italian). 2. Pisa: Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa.

- Parra, Maria Cecilia; Facella, Antonio, eds. (2011). Kaulonía, Caulonia, Stilida (e oltre). Indagini topografiche nel territorio (in Italian). 3. Pisa: Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa. ISBN 978-88-7642-418-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kaulonia. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Caulon. |

- Official website (Italian)

- Excavations of Caulonia by the University of Florence (Italian)