Cathedral of Ani

| Ani Cathedral | |

|---|---|

|

The cathedral in 2009  The location of the cathedral in Ani | |

| Basic information | |

| Location | Ani, Kars Province, Turkey |

| Geographic coordinates | 40°30′22″N 43°34′23″E / 40.506206°N 43.572969°ECoordinates: 40°30′22″N 43°34′23″E / 40.506206°N 43.572969°E |

| Affiliation | Armenian Apostolic Church |

| Architectural description | |

| Architect(s) | Trdat |

| Architectural type | Domed basilica |

| Architectural style | Armenian |

| Groundbreaking | 989 |

| Completed | 1001 or 1010 |

| Length | 34.3 m (113 ft)[1] |

| Width | 21.9 m (72 ft)[1] or 24.7 m (81 ft)[2] |

| Height (max) | 20 m (66 ft)[3] |

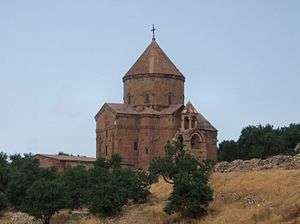

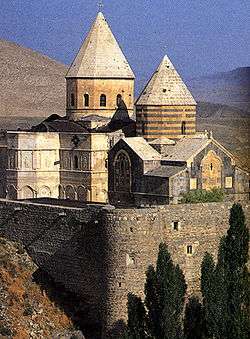

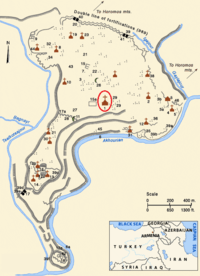

Ani Cathedral (Armenian: Անիի մայր տաճար, Anii mayr tačar; Turkish: Ani Katedrali) is a partially ruined Armenian church in the abandoned medieval city of Ani, located in present-day eastern Turkey, on the border with modern Armenia. It was completed in the early 11th century (1001 or 1010) by the architect Trdat and served, until the mid-11th century, as the seat of the catholicos, the head of the Armenian Apostolic Church.

In 1064, following the Seljuk conquest of Ani, the cathedral was converted into a mosque. It later returned to being used as an Armenian church. It eventually suffered damage in a 1319 earthquake when its conical dome collapsed. Subsequently, Ani was gradually abandoned. The north-western corner of the church was heavily damaged by a 1988 earthquake.

The cathedral is considered the largest and most impressive structure of Ani. It is a domed basilica with a rectangular plan, though the dome and most of its supporting drum are now missing.

Names

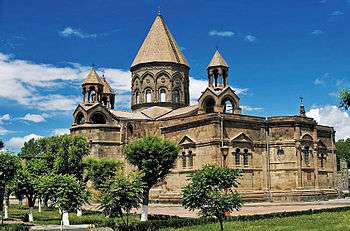

In modern times, the cathedral is referred to in Armenian as Անիի մայր տաճար, Anii mayr tačar and Turkish as Ani Katedrali,[4] both meaning "cathedral of Ani". Historically, however, it was known as Անիի Կաթողիկե, Anii Kat'oghike.[5][6] Kat'oghike is a term used for several cathedrals, such as Etchmiadzin Cathedral, Armenia's mother church.[7] The cathedral has also been referred to as "Holy Mother of God Church of Ani" (Անիի Սուրբ Աստվածածնի եկեղեցի, Anii Surb Astvatsatsni yekeghetsi;[2][8] Turkish: Meryem Ana Katedral)[9] or "Great Cathedral" (Մեծ Կաթողիկե, Mets Kat'oghike;[10] Turkish: Büyük Katedral).[11][12][13]

History

Foundation and early history

The construction of the cathedral began in 989 and was completed either in 1001[15][3][16][17][18][19] or 1010.[20] According to Maranci the generally accepted date of completion is 1001, but it may have extended until 1010.[21] The contradiction is based on the reading of the inscription of the cathedral's northern wall.[22][23] The scholarly consensus is that the architect Trdat was hired by the Bagratid King Smbat II to build a cathedral in Ani, the new capital of the Armenian kingdom.[21] Besides the cathedral, Trdat is credited with the repair of the dome of the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople.[15][19] The construction was halted when Smbat died in 989, according to an inscription on the south wall.[24][2] Trdat returned from Constantinople in 993.[25] The construction was continued by Queen Katranide[2][3][19] (also spelled Katramide),[26] the wife of King Gagik I, Smbat's brother and successor.[24][23] Maranci suggested what she describes as an "extremely tentative" hypothesis that the relatively large proportion of the cathedral may have been a "reflection of Trdat's memory of the vast continuous spaces of the Hagia Sophia."[27] The cathedral served as the seat of the catholicos,[26] the head of the Armenian Apostolic Church from its foundation in 1001[28] until the mid-11th century (1046 or 1051).[29][30] Thus, for around half a century Ani was the religious and political center of Armenia.[28]

A silver cross originally stood on its conical dome and a crystal chandelier, bought by King Smbat II from India, hang in the cathedral. In the 1010s, during the reign of Catholicos Sarkis I, a mausoleum dedicated to the Hripsimean virgins was erected next to the cathedral. The mausoleum was built on some of the remnants of the virgins brought from Vagharshapat.[26] In the 1040s-1050s inscriptions were left on the cathedral's eastern and western walls about urban projects, such as restoration of defense walls, installation of water pipes and easing of the tax burden on the people of Ani.[2]

Later history

Ani was conquered by the Seljuks, led by Alp Arslan, in 1064. Consequently, the cathedral was converted into a mosque[2][9] and called Fethiye Mosque[32] (Turkish: Fethiye Cami,[9][12][13][33] which translates to "victory mosque"[23][34] or "conquer[ed] mosque").[35] Official Turkish sources often refer to it by that name.[36] In 1124 a crescent was placed on the cathedral's dome by the Shaddadid amir of Ani. In response, the Armenian population encouraged King David IV of Georgia to seize Ani, after which the cathedral returned to Christian usage.[2][23] However, only two years later, in 1126, Ani came under the control of the Shaddadids.[2] During the 12th century historians Mkhitar Anetsi, Samuel Anetsi and philosopher Hovhannes Sarkavag served at the cathedral in various capacities.[2] Mkhitar Anetsi was an elder priest at the cathedral in the second half of the 12th century.[37] In 1198 Ani was conquered by the Georgian-Armenian Zakarid princes, under whose control the cathedral prospered. In 1213 the wealthy merchant Tigran Honents restored the cathedral's stairs.[2]

Decay

The earthquake of 1319 left the city devastated and resulted in the collapse of the cathedral's conical roof.[2][3][23] The drum reportedly collapsed during an 1832 earthquake.[23] The north-western corner of the cathedral was heavily damaged by a 1988 earthquake with its epicenter in modern Armenia's north.[2] It resulted in a large gaping hole. According to one source it also caused "a serious rent in the south-west corner; by 1998 parts of the roof here had started to fall."[23] Lavrenti Barseghian wrote in a 2003 article that the damage from the earthquake was so great that the entire building would collapse unless strengthened and restored.[38]

Architecture

The cathedral is considered a masterpiece of Armenian architecture.[lower-alpha 1] It is the largest and most impressive structure of Ani.[34][41] Authors of Global History of Architecture wrote that it "deserves to be listed among the principal monuments of the time because of its pointed arches and clustered columns and piers."[16] The cathedral is known for its novel design features.[8]

The cathedral is 34.3-metre (113 ft) long and 21.9-metre (72 ft) or 24.7-metre (81 ft) wide.[lower-alpha 2] It stood at 20-metre (66 ft) high,[3] and was Ani's tallest structure.[5] It is "a very large building by standards of Armenian architecture,"[8] but is considered small, "if judged by a European standard," wrote H. F. B. Lynch and added, "it is nevertheless a stately building. It bears the imprint of that undefinable quality, beauty, and can scarcely fail to arouse a thrill of delight in the spectator."[42] A BBC Travel writer described it as "imposing" and a "rust-coloured brick redoubt".[43] Architecture historian Murad Hasratyan suggests that its relatively large size and rich ornaments symbolize the revived Armenian statehood under the Bagratids.[2] French archaeologist Jacques de Morgan wrote of the cathedral: "This superb structure, though partly in ruins today, is still majestic in the purity of its lines and the chasteness of its carvings."[44]

The church's plan is defined as a domed basilica,[23] which is the result of a "fusion between basilica and central plan."[17] The dome was supported on pendentives and stood atop the "intersection of four barrel vaults elevated to a cruciform design and topped with gabled roofs." In the interior, "freestanding piers divide the space into three aisles, the nave of which terminates in an eastern apse flanked by two story side chapels."[45] Adalian wrote, "Although from the exterior, the domed basilica with blind arcades spoke of artistic refinement, the interior with its pointed arches and clustered piers rising to the ribbed ceiling vaults, included innovations whose parallels would appear in Gothic architecture in Western Europe a century later."[8] A journalist for RFE/RL noted, "Though the cathedral looks like a doll's house from the outside, the dimensions inside are awe-inspiring."[46]

Influence on Armenian architecture

The St. Saviour Church in Gyumri, Armenia's second largest city, was completed in 1873. Its ground plan is based on that of Ani Cathedral.[47][48] However, the church is not a replica of the cathedral and is significantly larger.[49]

Martin Conway considered the main church of the Marmashen monastery, dated 988-1029, a miniature of Ani Cathedral.[50]

Possible influence on Gothic architecture

Several European scholars have suggested that the volume composition of the interior elements of Ani Cathedral served to influence the development of Gothic architecture. According to World Monuments Fund the cathedral is "often considered a source of inspiration for many of the key features of Gothic architecture, which became a dominant architectural style in western Europe more than a century later."[40] The Ambassadors Fund for Cultural Preservation suggested: "In Ani, the stone ruins of the Great Cathedral — considered a masterpiece of medieval Armenian architecture — [bears] silent witness to the origins of the Western Gothic style."[51] The theory was popularized by Josef Strzygowski in the early 20th century. Strzygowski wrote in Origin of Christian Church Art: "It is a delight, in a church earlier than AD 1000, to see the builder, the court architect Trdat, carrying Armenian art so logically and so successfully past 'Romanesque' to 'Gothic'."[lower-alpha 3] Strzygowski argued that Ani Cathedral "should be considered the eastern source of the Gothic style. From the European point of view, this cathedral was the most valuable achievement ever created by Armenian architecture."[53] H. F. B. Lynch in his book on Armenia published in 1901, predating Strzygowski, wrote:[54]

The interior is quite remarkable from the standpoint of the history of architecture; it is also calculated to deserve the admiration of the lover of art. It has many of the characteristics of the Gothic style, of which it establishes the Oriental origin. [...] The impression which we take away from our survey of these various features is that we have been introduced to a monument of the highest artistic merit, denoting a standard of culture which was far in advance of the contemporary standards in the West.

William Lethaby found the church "strangely western"[56] "because its pointed arches, clustered piers, ribs and colonnades correspond to the Gothic of a hundred years later."[52] Although Adrian Stokes saw Ani Cathedral as holding "some balance between wall architecture and the linear Gothic to come," he did not find "the feeling for mass and space that transfixes him at Rimini or Luciano Laurana’s Quattro Cento courtyard in the Palace of Urbino."[52] David Roden Buxton wrote on the topic in 1937:[57]

The cathedral of Ani is worthy (if, indeed, it still exists) of far greater renown that actually surrounds it. Outside, it is a fine specimen of building in the typical Armenian manner, with blind arcades of great beauty. But inside it bears the semblance of a Gothic cathedral such as Western Europe might have seen two centuries later. Pairs of clustered columns support a high pointed vault, and on either side is an aisle with narrow pointed arches like those of the "Early English" style. It is assuredly a striking example of parallel evolution, even if all idea of a connection with the Gothic must be dismissed.

The theory has found wide support among Armenian architecture historians, such as Toros Toramanian,[3] Tiran Marutuan,[58] Murad Hasratyan.[lower-alpha 4] New York Times journalist Stephen Kinzer wrote in a 2000 article that the cathedral "looks as if it could have inspired Gothic architects in Europe."[41] The website Virtual Ani writes that though the use of pointed arches, among other things, "gives an impression of powerful verticality similar to that found in Gothic architecture (which this building predates by several centuries)", there is "no evidence to indicate that there was a connection between Armenian architecture and the development of the Gothic style in Western Europe."[23]

Recent developments

In 1989 a series of events under the title "The Glory of Ani" commemorating the millennium of the Cathedral of Ani took place in the United States, sponsored by the Eastern Prelacy of the Armenian Apostolic Church of America. A symposium took place at the New-York Historical Society on October 21, 1989.[59][60]

On July 23, 2008 Turkish President Abdullah Gül visited Ani and the cathedral.[61]

Since 2011 graduation ceremonies of some departments of the Yerevan State University have taken place at the cathedral.[62] While folk dance director Gagik Ginosyan and his wife, along with their friends, staged a wedding ceremony at the cathedral.[62] On September 10–12, 2011 researchers of the Shirak Armenology Research Center of the National Academy of Sciences of Armenia made a pilgrimage to the cathedral, where they performed scientific readings on history of Ani.[63]

2010 prayer controversy

On October 1, 2010 some two thousand people,[33] including senior members of the far-right Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), such as party leader Devlet Bahçeli, performed a Muslim prayer to commemorate the Alp Arslan-led Seljuk conquest of Ani in 1064. The event was widely seen as a nationalist retaliation for the Christian mass—the first since the Armenian Genocide of 1915—at the Cathedral of Aghtamar at Lake Van on September 19.[64][65][66] The prayer was authorized by the Ministry of Culture.[65] The crowd waved Turkish flags and chanted Allāhu Akbar before saying prayers in and around the cathedral.[36] It was attended by believers from Azerbaijan and broadcast live by three Azerbaijani TV channels.[67]

Reactions

Mahmut Esat Güven, an MP from the ruling AKP, denounced the prayer as an illegal "political show" connected with the Aghtamar mass.[32] According to Aris Nalcı of the Turkish-Armenian daily Agos, "This gesture was addressed to Turks, rather than Armenians."[68] According to commentary prepared by the Yapı Kredi Bank Economic Research, "the scene looked awkward to a large majority of Turks."[69] Hürriyet Daily News columnist Yusuf Kanlı described it as an "attempt [by Bahçeli] to woo and win back the lost nationalist-conservative vote."[70] Turkish-Armenian journalist Markar Esayan wrote in Today's Zaman: "what MHP leader Devlet Bahçeli did at Ani was in fact exploitation of religion."[71]

The prayer was received negatively among Armenian circles. The Armenian Apostolic Church, in an issued statement, accused the Turkish authorities in "destroying Armenian monuments and misappropriating historical Armenian holy sites and cultural treasures."[36] Architecture scholar Samvel Karapetyan commented sarcastically: "We now have reason to be happy. For centuries, our churches were desecrated and turned into toilets, whereas now they are only doing a namaz [sic]."[36] Art historian Heghnar Zeitlian Watenpaugh described the event as an example of "political stagecraft."[66]

Preservation efforts

Ani has been listed on the World Monuments Watch by World Monuments Fund (WMF) since 1996.[72] In May 2011 the WMF and the Turkish Ministry of Culture launched what they call a conservation project focusing on the cathedral and the nearby Church of the Redeemer.[73] The project is funded by the Ambassadors Fund for Cultural Preservation of the U.S. State Department.[51] Before the project a steel structure was installed around the cathedral, said to prevent its cracked sandstone walls from collapsing.[72] The WMF and its Turkish partner, the NGO Anadolu Kültür, say they will work on "stabilization and protection" of the cathedral.[40] Turkey's Minister of Culture Ertuğrul Günay stated "We hope that giving new life to the remains of once-splendid buildings, such as the Ani Cathedral and church, will bring new economic opportunities to the region."[73][74] The Deputy Minister of Culture Arev Samuelyan responded by saying in an interview that there is no restoration project, "at least our experts have not seen any." She accused Turkey in engaging in propaganda to showcase the international community supposed willingness in preserving Armenian monuments.[75] Furthermore, according to Gagik Gyurjyan, president of ICOMOS-Armenia, the Turkish Ministry of Culture rejected the preliminary agreement between Anadolu Kültür and the Armenian side to engage Armenian experts in restoration works. Osman Kavala, president of Anadolu Kültür, stated that the lack of formal bilateral relations between Armenia and Turkey may have prevented Armenian experts from being included in the project. Kavala stated in a 2011 interview that an estimated $1 million would be spent on the project, which was scheduled to start in 2012 and end in 4 years.[76]

The archaeological site of Ani was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site on July 15, 2016.[77] According to art historian Heghnar Zeitlian Watenpaugh the addition "would secure significant benefits in protection, research expertise, and funding."[78]

Gallery

plan[1]

plan[1] Watercolour by Arshak Fetvadjian, 1905

Watercolour by Arshak Fetvadjian, 1905 Western façade

Western façade South & west sides, with the Church of the Redeemer behind

South & west sides, with the Church of the Redeemer behind Interior view

Interior view Detail on the south façade

Detail on the south façade

References

- notes

- ↑ "a masterpiece of Armenian medieval architecture"[40] "հայ ճարտարապետության գլուխգործոցներից մեկը"[38]

- ↑ According to Toros Toramanian's plan: 34.3 by 21.9 metres (113 by 72 ft).[1] According to Murad Hasratyan: 34.3 by 24.7 metres (113 by 81 ft).[2]

- ↑ Strzygowski, Origin of Christian Church Art, pp. 72–3[52]

- ↑ Եկեղեցու ներսի այդպիսի լուծումը, հատկապեսմույթերի՝ ջլաղեղների նմանությամբ մասնատումը XII–XIV դդ. դարձել են Արմ. Եվրոպայում ձևավորված ու տարածված գոթական ճարտարապետության բնորոշ հատկանիշները: Իր այս առանձնահատկությունների, կառուցվածքային կատարելության և գեղաշուք հարդարանքի շնորհիվ Անիի Մայր տաճարը դասվում է համաշխարհային ճարտարապետության լավագույն ստեղծագործությունների թվին:[2]

- references

- 1 2 3 4 Strzygowski 1918, p. 185.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Hasratyan, Murad (2002). "Անիի Մայր Տաճար [Ani Cathedral]". armenianreligion.am (in Armenian). Yerevan State University Institute for Armenian Studies.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Անիի Մայր տաճար [Ani Cathedral]". Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia Volume I (in Armenian). 1974. p. 413.

- ↑ "Ani Tarihi Kenti (Kars)". kulturvarliklari.gov.tr (in Turkish). Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism, Cultural Assets and Museums General Directorate.

Ani Katedrali (Fethiye Camii)

- 1 2 Petrosyan, Sargis; Petrosyan, Lusine (2014). "Անին և Երվանդունիները [Ani and the Orontids of Armenia]". Research Papers (in Armenian). Shirak Armenology Research Center, National Academy of Sciences of Armenia (14): 27.

Անիում Սուրբ Աստվածածնի պաշտամունքի մասին է խոսում այն փաստը, որ քաղաքի ամենաբարձր շինությունը' Մայր տաճարը (Կաթողիկե եկեղեցին), ձոնված Էր նրան:

- ↑ Avagyan 1979, p. 70.

- ↑ Matevosyan, Karen (2009). "Արուճի և Թալինի պատմության էջեր [Histories of Aruch and Talin]". Etchmiadzin (in Armenian). Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin. 65 (1): 52.

Եկեղեցիներին տրվող «Կաթողիկե» անունն ունի երկու նշանակություն՝ գմբեթավոր և գլխավոր։ Այդպես են կոչվել էջմիածնի Մայր տաճարը, Դվինի կաթողիկոսարանի եկեղեցին, ավելի ուշ՝ Անիի Մայր տաճարը։

- 1 2 3 4 Adalian, Rouben Paul (2010). Historical Dictionary of Armenia. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-8108-7450-3.

- 1 2 3 Sağsöz, Onur (31 October 2008). "Ermenistan'a Ani için rica". Hürriyet (in Turkish).

- ↑ Matevosyan 2008, p. 5.

- ↑ Watenpaugh 2014, p. 532.

- 1 2 "Büyük Katedral (Fethiye Cami) - Kars". kulturportali.gov.tr (in Turkish). Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism.

- 1 2 Erzeneoğlu, Abdulkadir (26 April 2012). "Ani Harabeleri, günümüzde yeterince tanınmadı" (in Turkish). Cihan News Agency.

...1001 yılında yapımı tamamlanan Büyük Katedral yani Fethiye Cami...

- ↑ Lübke, Wilhelm (1881). Cook, Clarence, ed. Outlines of the History of Art Volume I. New York: Dodd, Mead, and Company. p. 440.

- 1 2 Maranci 2003, p. 294.

- 1 2 Ching, Francis D. K.; Jarzombek, Mark M.; Prakash, Vikramaditya (2010). A Global History of Architecture. John Wiley & Sons. p. 355. ISBN 9781118007396.

- 1 2 "Ani Cathedral". Armenian Studies Program California State University, Fresno. Archived from the original on 10 September 2012.

- ↑ Kazaryan, A.; Mikhaylov, P. (3 March 2009). "Ани [Ani]". Orthodox Encyclopedia Volume II (in Russian). Russian Orthodox Church. pp. 433–434.

Кафедральный собор А. (989-1001, наос 22´ 34 м, зодчий Трдат), 4-столпный крестово-купольный храм, построен при католикосе Хачике I Аршаруни.

- 1 2 3 "Historic City of Ani". UNESCO. 2012.

The Cathedral of Ani is one of the most important buildings in the site. Commissioned by the Armenian King Smbat Bagratuni II in 989, it was completed by his successor’s wife, Queen Katranidē by 1001. Its architect, Trdat, also participated in repairing the dome of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople.

- ↑ Hewsen, Robert H. (2001). Armenia: A Historical Atlas. University of Chicago Press. p. 114. ISBN 0-226-33228-4.

- 1 2 Maranci 2003, p. 304.

- ↑ Avagyan 1979, pp. 70-71.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "The Cathedral of Ani". virtualani.org. Virtual Ani.

- 1 2 Maranci 2003, p. 299.

- ↑ Hasratyan 2011, p. 13.

- 1 2 3 Matevosyan 2008, p. 11.

- ↑ Maranci 2003, pp. 302, 304.

- 1 2 Matevosyan, Rafayel (1978). "Անին արքունի աթոռանիստ և մայրաքաղաք [Ani as royal residence and capital]". Lraber Hasarakakan Gitutyunneri (in Armenian) (5): 93–94.

Սմբատ Բ ֊ն սկիզբ դրեց նոր կաթողիկեի կառուցմանը Անիում, որը ավարտվեց 1001 թ.՝ Գագիկ Ա֊ի օրոք։ Այսպիսով կաթողիկոսարանը տեղափոխվեց մայրաքաղաք, որտեղ կենտրոնացավ թե՛ աշխարհիկ և թե՛ հոգևոր գերագույն իշխանությունը:

- ↑ Matevosyan, K. (2002). "Անիի կաթողիկոսարան [Ani Catholicosate]" (in Armenian). Yerevan State University Institute for Armenian Studies.

- ↑ "The Hierarchical Sees - Locations". armenianchurch.org. Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin.

- ↑ Lynch 1901, p. 370.

- 1 2 "Turkey Approves Muslim Prayer Service In Armenian Church". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 1 October 2010.

- 1 2 Yardimciel, Mukadder; Özonur, Nursima; Tercanlı, Kürşat (1 October 2010). "Bahçeli ve 2 bin MHP'li, Ani'de namaz kıldı". Radikal (in Turkish).

- 1 2 Campbell, Verity (2007). Turkey. Lonely Planet. p. 582. ISBN 9781741045567.

...the cathedral, renamed the Fethiye Camii (Victory Mosque) by the Seljuk conquerors, is the largest and most impressive of the buildings.

- ↑ Özükan, Bülent (2003). "Virgin Mary Cathedral". Türkiye'nin kutsal mekanları [Holygrounds of Turkey]. Boyut Yayın.

After the seizure of Ani by Alparslan in 1064, it was converted to a mosque and was called as Fethiye (Conquer) Mosque.

- 1 2 3 4 Danielyan, Emil (8 October 2010). "Turkish Nationalist Rally In Church Angers Armenians". Eurasia Daily Monitor. 7 (182). The Jamestown Foundation. Archived from the original on 2016-02-13.

- ↑ Poghossian Rev. Fr. Matheos (2009). "Հառիճավանքը դարերի հոլովույթում [The Monastery of Harij in the course of centuries]". Etchmiadzin (in Armenian). Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin. 65 (3): 66.

- 1 2 Barseghian, Lavrenti (2003). "Կրկին անգամ Անի-Երերույք պատմա-հնագիտական միջազգային արգելոց կազմակերպելու հարցի շուրջ [Once again about organization of the international historical archeological reserve in Ani-Yereruyk]". Issues of the history and historiography of the Armenian Genocide (in Armenian) (8): 7.

Նախնական տվյալների համաձայն 1988թ. դեկտեմրերի 7-ի երկրաշարժից մեծապես տուժել է հայ ճարտարապետության գլուխգործոցներից մեկը' Անիի Մայր տաճարը, որը կառուցվել է 1001 թվականին: Փլուզվել է տաճարի հյուսիս-արևմտյան անկյունը, որի հետևանքով խարխլվել է ամբողջ կառույցը և եթե անհրաժեշտ վերանորոգման և ամրացման աշխատանքներ չձեռնարկվեն, ապա մոտ ապագայում ավերակի կույտի կվերածվի դեռևս կանգուն եկեղեցին:

- ↑ Strzygowski 1918, p. 187.

- 1 2 3 "Ani Cathedral". World Monuments Fund.

- 1 2 Kinzer, Stephen (8 October 2000). "A Hidden Empire in Turkey". The New York Times.

- ↑ Lynch 1901, p. 371.

- ↑ Flaherty, Joseph (15 March 2016). "The empire the world forgot". BBC Travel.

- ↑ de Morgan, Jacques (1918). The history of the Armenian people, from the remotest times to the present day. Ernest F. Barry (translator). Boston: Hairenik Association. p. 168.

Sembat died just after he had laid the foundations of the magnificent Ani cathedral (989). This superb structure, though partly in ruins today, is still majestic in the purity of its lines and the chasteness of its carvings.

- ↑ Maranci 2003, p. 301.

- ↑ "Turkey Turns Medieval Armenian Capital Into A Tourist Attraction". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 31 October 2014.

- ↑ "Giumri 12: Freedom Square: Surb Mair Astvatsatsin (Yot Verk), Surb Amenaprkich.". armenianheritage.org. Armenia Monuments Awareness Project.

Amenaprkich Cathedral. Constructed between the 1850s and 1870s, the cathedral is based on the 10th century cathedral of Ani...

- ↑ "Գյումրիի Սուրբ Ամենափրկիչը երեկ, այսօր և վաղը (լուսանկարներ)". 168 Hours (in Armenian). 7 August 2013.

- ↑ "St. All Saviours". gyumri.am. Gyumri Municipality.

- ↑ Conway, Martin (19 February 1916). "Churches of northern Armenia". Country Life. 39: 247.

...the ruined convent of Marmashen in the neighbourhood of Alexandropol. The two little buildings that remain stand in the rock banks of the Arpa Chai, a remote tributary of the Araxes. The church (988-1029) is a miniature of Ani Cathedral, but with a many-gabled dome such as was common in those days.

- 1 2 "Turkey: Preserving the Legacy of a Lost City". usembassy.gov. Ambassadors Fund for Cultural Preservation. 19 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 Kite, Stephen (September 2003). "'South Opposed to East and North': Adrian Stokes and Josef Strzygowski. A study in the aesthetics and historiography of Orientalism". Art History. 26 (4): 519.

- ↑ Marutian, Tiran (1990). "When Was Ani Cathedral Constructed?". The Armenian Review. 43 (3): 96.

- ↑ Lynch 1901, p. 372-373.

- ↑ "Անիի Աստվածամոր մայր տաճարը (1900)" (in Armenian). National Gallery of Armenia.

- ↑ Lethaby, William (1912). Medieval Art: From the Peace of the Church to the Eve of the Renaissance, 312-1350. London: Duckworth. p. 78.

Ani Cathedral, built about 1010, is especially remarkable in having the dome upborne on pointed arches built in several recessed orders rising from piers also ... This in Texier's plan, in Mr. Lynch's photograph, and Brossefs diagram of the interior, seems strangely western.

- ↑ Buxton, David Roden (1937). Russian Mediaeval Architecture with an Account of the Transcaucasian Styles and Their Influence in the West. Cambridge University Press. pp. 90–91.

- ↑ Marutyan, Tiran (1997). "Գոթակա՞ն, թե" հայ-գոթական ճարտարապետական ոճ [Gothic or Armenian-Gothic architecture?]". Garun (in Armenian) (7): 54–56.

- ↑ Watenpaugh 2014, p. 551.

- ↑ Zarian, A. K. (1990). "Անիի Մայր տաճարի հիմնադրման 1000-ամյակին նվիրված համաժողով Նյու Յորքում [A congress, devoted to the 1000th anniversary of Ani's Mother Temple foundation in New York]". Lraber Hasarakakan Gitutyunneri (in Armenian) (7): 91–94.

- ↑ Hakobyan, Tatul (21 June 2015). "Աբդուլլահ Գյուլը՝ Բագրատունյաց թագավորության երկու մայրաքաղաքներում. օրվա լուսանկարը [Abdullah Gül in two capitals of the Bagratids]" (in Armenian). ANI Armenian Research Center.

- 1 2 "Խոսող կոթողներ. Անիի Մայր տաճար [Talking monuments: Ani Cathedral]" (accompanying article) (in Armenian). Public Television of Armenia. 8 July 2015.

- ↑ Editorial Board. "Գիտական ընթերցումներ Անիի Մայր տաճարում [Scientific readings at Ani Cathedral]". Research Papers (in Armenian). Shirak Armenology Research Center, National Academy of Sciences of Armenia (14): 171–175.

- ↑ "Turkish nationalists rally in Armenian holy site at Ani". BBC News. 1 October 2010.

- 1 2 "Turkey's nationalist party holds Friday prayers at Ani ruins". Hürriyet Daily News. 1 October 2010.

- 1 2 Watenpaugh 2014, p. 544-545.

- ↑ "Անիում նամազ են անում [Namaz in Ani]". The Armenian Times (in Armenian). 1 October 2010.

- ↑ "Turkish Nationalists Pray In Ancient Armenian Cathedral". Armenian Service of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 2 October 2010.

- ↑ "General Outlook". Turkey Weekly Macro Comment. Yapı Kredi Bank, Strategic Planning and Research Section. 11 October 2010. pp. 2–3.

- ↑ Kanlı, Yusuf (1 October 2010). "Towards a two-party presidential Turkey". Hürriyet Daily News.

- ↑ Esayan, Markar (14 October 2010). "Religion and politics, and the recent 'surah wars' in the Turkish political arena". Today's Zaman.

- 1 2 Brown, Matthew Hay; Hacaoglu, Selcan (4 May 2011). "In gesture, Turkey conserving Armenian churches". The Baltimore Sun. via Associated Press.

- 1 2 "Turkey renovates Armenian monuments as gesture". Hurriyet Daily News. via Associated Press. 5 May 2011.

- ↑ "Cultural gesture: Turkey intends to restore the cathedral in ancient Armenian city of Ani". ArmeniaNow. 6 May 2011.

- ↑ "ՀՀ մշակույթի նախարարություն` Թուրքիան փոշի է փչում աշխարհի աչքերին Անիի մասին խոսելիս". mediamax.am (in Armenian). 7 June 2011.

- ↑ Hambardzumyan, Hasmik (21 May 2011). "Հայ մասնագետները կմասնացե՞ն Անիի Մայր Տաճարի վերականգնմանը. Պարզաբանում է "Անադոլու Կուլտուր"-ի ղեկավարը". panorama.am (in Armenian).

- ↑ "Five sites inscribed on UNESCO's World Heritage List". UNESCOPRESS. UNESCO. 15 July 2016.

- ↑ "Ani Included on UNESCO World Heritage List". Armenian Weekly. 15 July 2016.

- bibliography

- Maranci, Christina (2003). "The Architect Trdat: Building Practices and Cross-Cultural Exchange in Byzantium and Armenia". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 62 (3): 294–305. JSTOR 3592516.

- Hasratyan, Murad (2011). "Անիի ճարտարապետությունը [Architecture of Ani]". Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Armenian) (3): 3–27.

- Strzygowski, Josef (1918). Die Baukunst der Armenier und Europa [The Architecture of the Armenians and of Europe] Volume I (in German). Vienna: Vienna: Kunstverlag Anton Schroll & Co.

- Lynch, H. F. B. (1901). Armenia, travels and studies. Volume I: The Russian Provinces. London: Longmans, Green, and Co.

- Watenpaugh, Heghnar Zeitlian (2014). "Preserving the Medieval City of Ani: Cultural Heritage between Contest and Reconciliation". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 73 (4): 528–555. doi:10.1525/jsah.2014.73.4.528. JSTOR 10.1525/jsah.2014.73.4.528.

- Watenpaugh, Heghnar Z. (2014). "The Cathedral of Ani, Turkey: From Church to Monument". In Mohammad, Gharipour. Sacred Precincts: The Religious Architecture of Non-Muslim Communities Across the Islamic World (revised ed.). BRILL. pp. 460–473. doi:10.1163/9789004280229_027. ISBN 9789004280229.

- Matevosyan, Karen (2008). "Անին մայրաքաղաք և կաթողիկոսանիստ [Ani as a Capital and Catholicosate]". Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Armenian) (3): 3–30.

- Avagyan, Suren (1979). "Անիի Մայր տաճարի շինարարական արձանագրության տարեթվերը [Date of the construction inscription of Ani Cathedral]". Lraber Hasarakakan Gitutyunneri (in Armenian) (11): 70–77.

- Vardanian, R.H. (2000). "Անիի մայր տաճարի արձանագրության համաժամանակյա տարեթվերը [Synchronous dates of Ani cathedral inscription]". Lraber Hasarakakan Gitutyunneri (in Armenian) (1): 54–69.

- further reading

- Abroyan, Armen (2004). Անիի մայր տաճարի ճարտարապետությունը [Architecture of Ani Cathedral] (PhD thesis) (in Armenian). Yerevan State University of Architecture and Construction.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cathedral of Ani. |