Cat behavior

Cat behavior includes body language, elimination habits, aggression, play, communication, hunting, grooming, urine marking, and face rubbing in domestic cats. It varies among breeds and individuals, and between colonies.

Communication can vary greatly among individual cats. Some cats interact with other cats more easily than other cats. In a family with many cats, the interactions can change depending on which individuals are present and how restricted the territory and resources are. One or more individuals may become aggressive: fighting may occur with the attack resulting in scratches and deep bite wounds.

A cat's eating patterns in domestic settings (homes) can be unsettling for owners. Some cats "ask for" food dozens of times a day, including at night, with rubbing, pacing, and meowing.

Communication

Kittens need vocalization early on in order to develop communication properly. The change in intensity of vocalization will change depending on how loud their feedback is. Some examples of different vocalizations are described below.[1]

Purring –soft buzz, can mean that the cat is content or possibly that they are sick. Meows- this is a type of greeting that is used most often. Mews- usually happens when a mother is interacting with her young. Hissing or spitting- the cat is angry or defensive. The cat should be left alone. Yowls- can mean that the cat is in distress or feeling aggressive. Chattering- chattering their teeth. They do this when they are hunting or being restrained from hunting.[2]

Body language

Cats rely strongly on body language to communicate. A cat may rub against an object, lick a person, and purr. Much of a cat's body language is through its tail, ears, head position, and back posture. Cats flick their tails in an oscillating, snake-like motion, or abruptly from side to side, often just before pouncing on an object or animal in what looks like "play" hunting behavior. If spoken to, a cat may flutter its tail in response, which may be the only indication of the interaction, though movement of its ears or head toward the source of the sound may be a better indication of the cat's awareness that a sound was made in their direction.[3]

Scent rubbing and spraying

These behaviors are thought to be a way of marking territory. Facial marking behavior is used to mark their territory as "safe". The cat rubs its cheeks on prominent objects in the preferred territory, depositing a chemical pheromone produced in glands in the cheeks. This is known as a contentment pheromone. Synthetic versions of the feline facial pheromone are available commercially.[4][5]

Cats have anal sacs or scent glands. Scent is deposited on the feces as it is eliminated. Unlike intact male cats, female and neutered male cats usually do not spray urine. Spraying is accomplished by backing up against a vertical surface and spraying a jet of urine on that surface. Unlike a dog's penis, a cat's penis points backward. Males neutered in adulthood may still spray after neutering. Urinating on horizontal surfaces in the home, outside the litter box may indicate dissatisfaction with the box, due to a variety of factors such as substrate texture, cleanliness and privacy. It can also be a sign of urinary tract problems. Male cats on poor diets are susceptible to crystal formation in the urine which can block the urethra and create a medical emergency.

Body postures

A cat's posture communicates its emotions. It is best to observe cats' natural behavior when they are by themselves, with humans, and with other animals.[6] Their postures can be friendly or aggressive, depending upon the situation. Some of the most basic and familiar cat postures include the following:[7][8]

- Relaxed posture – The cat is seen lying on the side or sitting. Its breathing is slow to normal, with legs bent, or hind legs laid out or extended. The tail is loosely wrapped, extended, or held up. It also hangs down loosely when the cat is standing.

- Stretching posture – another posture indicating cat is relaxed.

- Yawning posture – either by itself, or in conjunction with a stretch: another posture of a relaxed cat.

- Alert posture – The cat is lying on its belly, or it may be sitting. Its back is almost horizontal when standing and moving. Its breathing is normal, with its legs bent or extended (when standing). Its tail is curved back or straight upwards, and there may be twitching while the tail is positioned downwards.

- Tense posture – The cat is lying on its belly, with the back of its body lower than its upper body (slinking) when standing or moving back. Its legs, including the hind legs are bent, and its front legs are extended when standing. Its tail is close to the body, tensed or curled downwards; there can be twitching when the cat is standing up.

- Anxious/ovulating posture – The cat is lying on its belly. The back of the body is more visibly lower than the front part when the cat is standing or moving. Its breathing may be fast, and its legs are tucked under its body. The tail is close to the body and may be curled forward (or close to the body when standing), with the tip of the tail moving up and down (or side to side).

- Fearful posture – The cat is lying on its belly or crouching directly on top of its paws. Its entire body may be shaking and very near the ground when standing up. Breathing is also fast, with its legs bent near the surface, and its tail curled and very close to its body when standing on all fours.

- Terrified posture – The cat is crouched directly on top of its paws, with visible shaking seen in some parts of the body. Its tail is close to the body, and it can be standing up, together with its hair at the back. The legs are very stiff or even bent to increase their size. Typically, cats avoid contact when they feel threatened, although they can resort to varying degrees of aggression when they feel cornered, or when escape is impossible.[9]

-

Relaxing cat

-

Stretching cat

-

Yawning cat

-

Alert posture

-

Tense posture

-

Fearful posture

-

.jpg)

Terrified posture

Vocal calls

- Purring – Purring occurs with contentment or pleasure, and pain such as labour. The mechanism of purring is suspected to be minute vibrations in the voice box.

- Meowing and mewing

- Greeting – A particular sort of vocalization, such as a low meow or chirp or a bark, possibly with simultaneous purring.

- Distress – Mewing is a plea for help or attention often made by kittens. There are two basic types of this call, one more loud and frantic, the other more high-pitched. In older cats, it is more of a panicky repeated meow.

- Attention – Often simple meows and mews in both older cats and young kittens. A commanding meow is a command for attention, food, or to be let out.

- Protest – Whining meows.

- Happy – A meow that starts with a low pitch, goes up, and comes back down.

- Frustration – A strong sigh or exhaled snort.

- Watching – Cats will often "chatter" or "chirrup" on seeing something of interest. This is sometimes attributed to mimicking birdsong to attract prey or draw others' attention to it when they are unable to attack the prey themselves, but often birds are not present.[10]

Kneading

Kittens "knead" the breast while suckling, using the forelimbs one at a time in an alternating pattern to push against the mammary glands to stimulate lactation in the mother.

Cats carry these infantile behaviors beyond nursing and into adulthood. Some cats "nurse", i.e. suck, on clothing or bedding during kneading. The cat exerts firm downwards pressure with its paw, opening its toes to expose its claws, then closes its claws as it lifts its paw. The process takes place with alternate paws at intervals of one to two seconds. They may knead while sitting on their owner's lap, which may prove painful if the cat has sharp claws.

Since most of the preferred "domestic traits" are neotenous or juvenile traits that persist in the adult, kneading may be a relic juvenile behavior retained in adult domestic cats.[11] It may also "stimulate" the cat and make it feel good, in the same manner as a human stretching. Kneading is often a precursor to sleeping. Many cats purr while kneading. They also purr mostly when newborn, when feeding, or when trying to feed on their mother's teat. The common association between the two behaviors may corroborate the evidence in favor of the origin of kneading as a remnant instinct.[12]

Panting

Unlike dogs, panting is a rare occurrence in cats, except in warm weather environments. Some cats may pant in response to anxiety, fear or excitement. It can also be caused by play, exercise, or stress from things like car rides. However, if panting is excessive or the cat appears in distress, it becomes important to identify the underlying cause, as panting may be a symptom of a more serious condition, such as a nasal blockage, heartworm disease, head trauma, or drug poisoning. If panting continues, the owner should consult a veterinarian.[13] In many cases, feline panting, especially if accompanied by other symptoms, such as coughing or shallow breathing (dyspnea), is considered to be abnormal, and treated as a medical emergency.[14]

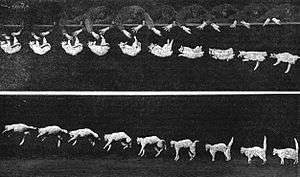

Righting reflex

The righting reflex is the attempt of cats to land on their feet at the completion of a jump or a fall. They can do this more easily than other animals due to their flexible spine, floating collar bone, and loose skin. Cats also use vision and/or their vestibular apparatus to help tell which way to turn. They then can stretch themselves out and relax their muscles. The righting reflex does not always result in the cat landing on its feet[15] at the completion of the fall.

Food eating patterns

Cats are obligate carnivores, and do not do well on vegetarian diets. Felines in the wild usually hunt smaller mammals to keep themselves nourished. Many cats find and chew small quantities of long grass but this is not for its nutritional value per se. The eating of grass seems to stem from feline ancestry and has nothing to do with dietary requirements. It is said that feline ancestors instead ate grass for the purging of intestinal parasites.[16]

Another thing to note is that cats have a very small amount of taste buds on their tongue. They actually can’t taste sweet things at all. Cats mainly smell for their food and what they taste for is amino acids instead. This however can be the reason that cats are now being diagnosed with diabetes. The food that domestic cats get have a lot of carbohydrates in them and even through domestication high sugar content still has a hard time in the digestive system of cats.[17]

Although one might think that cats regularly drink water this is a myth. Cats will lap at water usually for pure amusement, not because they are thirsty. The way the water moves as they lap at the water entrances them and makes them continue to drink. In the wild cats get their water from the prey they eat and not from actual water. Even through thousands of years of domestication humans have been unsuccessful at getting rid of this behavior.[18]

Socialization

Some kittens are naturally afraid of people at first, but if handled and well cared for in the first 16 weeks, they become friendly with the humans who care for them. They often engage in play-fighting, with non-aggressive biting, chewing, scratching, and rapidly repetitive leg-kicking. To decrease the odds of a cat being unsocial or hostile towards humans, kittens should be socialized at an early age.

Feral kittens around two to seven weeks old can be socialized usually within a month of capture.[19] This period of time is the kitten’s socialization period and is the only time a cat can socialize with humans.[20] Some species of cats cannot be socialized towards humans because of things like genetic influence and in some cases specific learning experiences.[21] The best way to get a kitten to socialize with you is to handle the kitten for about 5 hours a week according to some studies.[22] The process is made easier if there is another socialized cat present but not necessarily in the same space as the feral. If the handler can get a cat to urinate in the litter tray, then the others in a litter will usually follow. Initial contact with thick gloves is highly recommended until trust is established, usually within the first week. It is a challenge to socialize an adult. Socialized adult feral cats tend to trust only those who they trusted in their socialization period, and therefore can be very fearful around strangers.[23]

Cats can be extremely friendly companions. Cats become social between the second and seventh week of life. During this time, social skills are developed.[24] Kittens are curious creatures and mistake anything, and anyone, for being a toy. Supplying toys and climbing poles helps to keep them occupied while they are being slowly socialized.

The strength of the cat–human bond is mainly correlated with how much consideration is given to the cat's feelings by its human companion. Kittens should be gently handled for 15–40 minutes a day.[25] Holding the kitten as much as possible provides the kitten feelings of warmth, love, and safety. It is especially soothing for the kitten to hear the heart beat of its owner.[26] This is a crucial bonding period, which will help develop larger brains, make the kittens more exploratory, and playful, and better learners.[27] The formula for a successful relationship thus has much in common with human-to-human relationships. If these skills are not acquired, in the first eight weeks, they may be lost forever.

Some people regard cats as sneaky, shy, or aloof animals. Feline shyness and aggression around people is often a result of lack of socialization. Cats relate to humans differently from dogs, spending some time on their own each day as well as time with humans.

Cats have a strong "escape" instinct. Attempts to corner, capture or herd a cat can thus provoke powerful fear-based escape behavior. Socialization is a process of learning that many humans can be trusted. When a human extends a hand slowly towards the cat, to enable the cat to sniff the hand, this seems to start the process.

There is a widespread belief that relationships between dogs and cats are problematic. However, both species can develop amicable relationships. The order of adoption may also cause significant differences in their relationship. Sometimes, the dog may be simply looking to play with the cat while the cat may feel threatened by this approach and lash out with its claws, causing painful injury. Such an incident may cause an irreversible animosity between the cat and dog.

Cat environment

Cats like to organize their environment based on their needs. Like their ancestors, domestic cats still have an inherent desire to maintain an independent territory but are generally content to live with other cats for company as they easily get bored. Living alone for a longer time may let them forget how to communicate with other cats.[28]

Sometimes, however, adding a kitten to your family can be a bad idea. If you already have an older cat and wish to add another cat to their environment it would be best to get another older cat that has been socialized with other cats. When a kitten is introduced to a mature cat that cat may show something called feline asocial aggression where they feel threatened and act aggressive to drive off the intruders. If this happens separate the kitten and the cat and slowly introduce them by rubbing towels on the animals and presenting the towel to the other.[29]

Cats use scent/pheromones to help organize their territory by marking prominent objects. If these objects/scents are removed it upsets the cat's perception of its environment.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cat behavior. |

References

- ↑ Shipley, C; Buchwald, J.S; Carterette, E.C (January 1988). "The role of auditory feedback in the vocalizations of cats". Experimental Brain Research. 69 (2): 431–438.

- ↑ Anonumous (May 2015). "Interpreting feline vocalization patterns" (37). DMV360. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ↑ Pachel, Christopher (May 2014). "Intercat Aggression: Restoring Harmony in the Home: A Guide for Practitioners". The Veterinary clinics of North America. Small animal practice. 44 (3): 565–579.

- ↑ Dr. Jennifer Coates, DVM (22 April 2013). "Synthetic Feline Facial Pheromones: Making Recommendations in the Absence of Definitive Data, Part 1". petMD.

- ↑ {http://www.feliway.com/}

- ↑ "The Indoor Cat Initiative" (PDF). The Ohio State University, College of Veterinary Medicine. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ↑ "Test to determine how well you know feline body language".

- ↑ An Ethogram for Behavioural Studies of the Domestic Cat. UFAW Animal Welfare Research Report No 8. UK Cat Behaviour Working Group, 1995.

- ↑ "Reading Your Cat". Animal Planet. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ↑ Millburn, Naomi. "What Cats Make the Chirping Sound?". the nest. XO Group Inc. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ↑ Schwartz, Stefanie (June 2003). "Separation anxiety syndrome in dogs and cats". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 222 (11): 1526–32.

- ↑ McPherson, F.J; Chenoweth, P.J (April 2012). "Mammalian sexual dimorphism". Animal Reproduction Science. 131 (3-4): 109–122.

- ↑ Spielman, Dr. Bari. "Panting in Cats: Is It Normal?". Retrieved 2010-01-07.

- ↑ "Cat Panting Explained". The Cat Health Guide. Retrieved 2011-07-02.

- ↑ Adams, Cecil (1996-07-19). "Do cats always land unharmed on their feet, no matter how far they fall?". The Straight Dope. Chicago Reader. Retrieved 2007-11-07.

- ↑ Hart, Benjamin (Dec 2008). "Why do dogs and cats eat grass?". Veterinary Medicine. 103 (12): 648.

- ↑ Li, Xia (July 2006). "Cats lack a sweet taste receptor". the Journal of Nutrition. 136 (7): 1932S–1934S.

- ↑ Macdonald, Rogers (1984). "Nutrition of the domestic cat, a mammalian carnivore". Annual review of nutrition. 4: 521–562.

- ↑ Casey, Rachel; Bradshaw, John (November 2008). "The effects of additional socialisation for kittens in a rescue centre on their behaviour and suitability as a pet". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 114 (1-2): 196–205.

- ↑ Casey, Rachel; Bradshaw, John (November 2008). "The effects of additional socialisation for kittens in a rescue centre on their behaviour and suitability as a pet". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 114 (1-2): 196–205.

- ↑ Casey, Rachel; Bradshaw, John (November 2008). "The effects of additional socialisation for kittens in a rescue centre on their behaviour and suitability as a pet". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 114 (1-2): 196–205.

- ↑ Casey, Rachel; Bradshaw, John (November 2008). "The effects of additional socialisation for kittens in a rescue centre on their behaviour and suitability as a pet". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 114 (1-2): 196–205.

- ↑ Casey, Rachel; Bradshaw, John (November 2008). "The effects of additional socialisation for kittens in a rescue centre on their behaviour and suitability as a pet". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 114 (1-2): 196–205.

- ↑ "Socializing Your Kitten". ASPCA. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- ↑ "Socializing Your Kitten". ASPCA. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- ↑ "Kitten Socialization". Socializing Feral Cats. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- ↑ "Socializing Your Kitten". ASPCA. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- ↑ http://www.companionanimalpsychology.com/2012/06/one-kitten-or-two.html

- ↑ Beaver, Bonnie (September 2004). "Fractious cats and feline aggression". Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 6 (1): 13–18.