Carl Lewis

Frederick Carlton "Carl" Lewis (born July 1, 1961) is an American former track and field athlete, who won 10 Olympic medals, including nine gold, and 10 World Championships medals, including eight gold. His career spanned from 1979 to 1996 when he last won an Olympic title and subsequently retired. He is one of 3 Olympic athletes who won 4 gold medals in a single event (the others being Al Oerter and Michael Phelps).

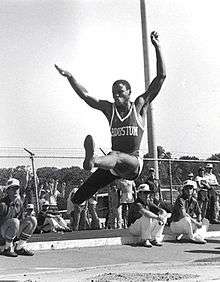

Lewis was a dominant sprinter and long jumper who topped the world rankings in the 100 m, 200 m and long jump events frequently from 1981 to the early 1990s. He set world records in the 100 m, 4 × 100 m and 4 × 200 m relays, while his world record in the indoor long jump has stood since 1984. His 65 consecutive victories in the long jump achieved over a span of 10 years is one of the sport's longest undefeated streaks. Over the course of his athletics career, Lewis broke ten seconds for the 100 meters 15 times and 20 seconds for the 200 meters 10 times.

His accomplishments have led to numerous accolades, including being voted "World Athlete of the Century" by the International Association of Athletics Federations and "Sportsman of the Century" by the International Olympic Committee, "Olympian of the Century" by Sports Illustrated and "Athlete of the Year" by Track & Field News in 1982, 1983, and 1984.

After retiring from his athletics career, Lewis became an actor and has appeared in a number of films. In 2011 he attempted to run for a seat as a Democrat in the New Jersey Senate, but was removed from the ballot due to the state's residency requirement. Lewis owns a marketing and branding company named C.L.E.G., which markets and brands products and services including his own.

Athletic career

Early life, and emergence as a competitive athlete

Frederick Carlton Lewis was born in Birmingham, Alabama, on July 1, 1961, the son of William and Evelyn Lewis. He grew up in a family of athletes. His mother (née Lawler) was a hurdler on the 1951 Pan-Am team.[2] His parents ran a local athletics club that provided a crucial influence on both Carl and his sister, Carol.[3] She was also to become an elite long jumper, finishing 9th at the 1984 Olympics and taking bronze at the 1983 World Championships.[4][5]

Lewis was initially coached by his father, who also coached other local athletes to elite status.[3] At age 13, Lewis began competing in the long jump, and he emerged as a promising athlete while coached by Andy Dudek and Paul Minore at Willingboro High School in his hometown of Willingboro Township, New Jersey.[2][6] He achieved the ranking of fourth on the all-time World Junior list of long jumpers.[2]

Many colleges tried to recruit Lewis, and he chose to enroll at the University of Houston where Tom Tellez was coach. Tellez would thereafter remain Lewis' coach for his entire career. Days after graduating from high school in 1979, Lewis broke the high school long jump record with a leap of 8.13 m (26 ft 8 in).[7] By the end of 1979, Lewis was ranked fifth in the world for the long jump, according to Track and Field News.[8]

At the end of the high school year, an old knee injury had flared up again, which might have had consequences on his fitness. However, working with Tellez, Lewis adapted his technique so that he was able to jump without pain and he went on to win the 1980 National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) title with a wind-assisted jump of 8.35 m (27 ft 4 1⁄2 in).[2]

Though his focus was on the long jump, he was now starting to emerge as a sprint talent. Comparisons were beginning to be made with Jesse Owens, who dominated sprint and long jump events in the 1930s. Lewis qualified for the American team for the 1980 Olympics in the long jump and as a member of the 4 × 100 m relay team.[2] The Olympic boycott meant that Lewis did not compete in Moscow but instead at the Liberty Bell Classic in July 1980, an alternate meet for boycotting nations. He jumped 7.77 m (25 ft 5 3⁄4 in) there for a Bronze medal, and the American 4 × 100 m relay team won Gold with a time of 38.61 s.[9] At year's end, Lewis was ranked 6th in the world in the long jump and 7th in the 100 m.[8][10]

Breakthrough in 1981 and 1982

At the start of 1981, Lewis' best legal long jump was his high school record from 1979. On June 20, Lewis improved his personal best by almost half a meter by leaping 8.62 m (28 ft 3 1⁄4 in) at the TAC Championships while still a teenager.[11]

While marks set at the thinner air of high altitude are eligible for world records,[12] Lewis was determined to set his records at sea level. In response to a question about his skipping a 1982 long jump competition at altitude, he said, "I want the record and I plan to get it, but not at altitude. I don't want that '(A)' [for altitude] after the mark."[13] When he gained prominence in the early 1980s, all the extant men's 100 m and 200 m records and the long jump record had been set at the high altitude of Mexico City.[12]

Also in 1981, Lewis became the fastest 100 m sprinter in the world. His relatively modest best from 1979 (10.67 s) improved to a world-class 10.21 the next year. But 1981 saw him run 10.00 s at the Southwest Conference Championships in Dallas on May 16, a time that was the third-fastest in history and stood as the low-altitude record.[14] For the first time, Lewis was ranked number one in the world, in both the 100 m and the long jump. He won his first national titles in the 100 m and long jump. Additionally, he won the James E. Sullivan Award as the top amateur athlete in the United States.[15]

In 1982, Lewis continued his dominance, and for the first time it seemed someone might challenge Bob Beamon's world record of 8.90 m (29 ft 2 1⁄4 in) in the long jump set at the 1968 Olympics, a mark often described as one of the greatest athletic achievements ever.[16] Before Lewis, 28 ft 0 in (8.53 m) had been exceeded on two occasions by two people: Beamon and 1980 Olympic champion Lutz Dombrowski. During 1982, Lewis cleared 28 ft 0 in (8.53 m) five times outdoors, twice more indoors, going as far as 8.7 m (28 ft 6 1⁄2 in) at Indianapolis on July 24.[17] He also ran 10.00 s in the 100 m, the world's fastest time, matching his low-altitude record from 1981. He achieved his 10.00 s clocking the same weekend he leapt 8.61 m (28 ft 2 3⁄4 in) twice, and the day he recorded his new low-altitude record 8.76 m (28 ft 8 3⁄4 in) at Indianapolis, he had three fouls with his toe barely over the board, two of which seemed to exceed Beamon's record, the third which several observers said reached 30 ft 0 in (9.14 m). Lewis said he should have been credited with that jump, claiming the track officials misinterpreted the rules on fouls.[18]

He repeated his number one ranking in the 100 m and long jump, and ranked number six in the 200 m. Additionally, he was named Athlete of the Year by Track and Field News. From 1981 until 1992, Lewis topped the 100 m ranking six times (seven if Ben Johnson's 1987 top ranking is ignored), and ranked no lower than third.[10] His dominance in the long jump was even greater, as he topped the rankings nine times during the same period, and ranked second in the other years.[8]

1983 and the inaugural World Championships

The International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF), the governing body of track and field, organized the first World Championships in 1983. Lewis' chief rival in the long jump was predicted to be the man who last beat him: Larry Myricks. But though Myricks had joined Lewis in surpassing 28 ft 0 in (8.53 m) the year before, he failed to qualify for the American team, and Lewis won at Helsinki with relative ease. His winning leap of 8.55 m (28 ft 0 1⁄2 in) defeated silver medalist Jason Grimes by 0.26 m (0 ft 10 in).[19]

He also won the 100 m with relative ease. There, Calvin Smith who had earlier that year set a new world record in the 100 m at altitude with a 9.93 s performance, was soundly beaten by Lewis 10.07 s to 10.21 s.[20] Smith won the 200 m title,[21] an event which Lewis had not entered, but even there he was partly in Lewis' shadow as Lewis had set an American record in that event earlier that year. He won the 200 m on June 19 at the TAC/Mobil Championships in 19.75 s, the second-fastest time in history and the low-altitude record, only 0.03 s behind Pietro Mennea's 1979 mark. Observers here noted that Lewis probably could have broken the world record if he did not ease off in the final meters to raise his arms in celebration.[22][23] Finally, Lewis ran the anchor in the 4 × 100 m relay, winning in 37.86 s, a new world record and the first in Lewis' career.[24]

Lewis' year-best performances in the 100 m and long jump were not at the World Championships, but at other meets. He became the first person to run a sub-10 second 100 m at low-altitude with a 9.97 s clocking at Modesto on May 14.[25][26] His gold at the World Championships and his other fast times earned him the number one ranking in the world that year, despite Calvin Smith's world record. At the TAC Championships on June 19, he set a new low-altitude record in the long jump, 8.79 m (28 ft 10 in)[22] and earned the world number one ranking in that event.[27] Track and Field News ranked him number two in the 200 m, despite his low-altitude record of 19.75 s, behind Smith, who had won gold at Helsinki.[28] Lewis was again named Athlete of the Year by the magazine.[29]

1984 Summer Olympics: emulating Jesse Owens

At the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles, Lewis was entered into four events with realistic prospects of winning each of them and thereby matching the achievement of Jesse Owens at the 1936 Games in Berlin.[30]

Lewis started his quest to match Owens with a convincing win in the 100 m, running 9.99 s to defeat his nearest competitor, fellow American Sam Graddy, by 0.2 s. In his next event, the long jump, Lewis won with relative ease. But his approach to winning this event stoked controversy, even as knowledgeable observers agreed his approach was the correct one.[31] Since Lewis still had heats and finals in the 200 m and the 4 × 100 m relay to compete in, he chose to take as few jumps as necessary to win the event. He risked injury in the cool conditions of the day if he over-extended himself, and his ultimate goal to win four golds might be at risk. His first jump at 8.54 m (28 ft 0 in) was, he knew, sufficient to win the event. He took one more jump, a foul, then passed his remaining four allotted jumps. He won gold, as silver medalist Gary Honey of Australia's best jump was 8.24 m (27 ft 0 1⁄4 in). But the public was generally unaware of the intricacies of the sport and had been repeatedly told by the media of Lewis' quest to surpass Bob Beamon's legendary long jump record of 8.90 m (29 ft 2 1⁄4 in). Lewis himself had often stated it was a goal of his to surpass the mark. A television advertisement with Beamon appeared before the final, featuring the record-holder saying, "I hope you make it, kid."[32] So, when Lewis decided not to make any more attempts to try to break the record, he was roundly booed. When asked about those boos, Lewis said, "I was shocked at first. But after I thought about it, I realized that they were booing because they wanted to see more of Carl Lewis. I guess that's flattering."[33]

His third gold medal came in the 200 m, where he won in a time of 19.80 s, a new Olympic record and the third fastest time in history. Finally, he won his fourth gold when the 4 × 100 m relay team he anchored finished in a time of 37.83 s, a new world record.[30]

Lack of endorsements and public perception

Although Lewis had achieved what he had set out to do, matching Jesse Owens' feat of winning four gold medals at a single Olympic Games, he did not win the lucrative endorsement deals which he had expected. The long jump controversy was one reason and his self-congratulatory conduct did not impress several other track stars: "He rubs it in too much," said Edwin Moses, twice Olympic gold medalist in the 400 m hurdles. "A little humility is in order. That's what Carl lacks."[34] Further, Lewis' agent Joe Douglas compared him to pop star Michael Jackson, a comparison which did not go over well. Douglas said he was inaccurately quoted, but the impression that Lewis was aloof and egotistical was firmly planted in the public's perception by the end of the 1984 Olympic Games.[35]

Additionally, rumors at the time that Lewis was gay circulated, and though Lewis denied the rumors, they probably hurt his marketability as well. Lewis' look at the Games, with a flattop haircut and flamboyant clothing, added fuel to the reports. "It doesn't matter what Carl Lewis's sexuality is," high jumper Dwight Stones said. "Madison Avenue perceives him as homosexual."[36] Coca-Cola had offered a lucrative deal to Lewis before the Olympics, but Lewis and Douglas turned it down, confident that Lewis would be worth more after the Olympics. But Coca-Cola rescinded the offer after the Games. Nike had Lewis under contract for several years already, despite questions about how it affected his amateur status, and he was appearing in Nike television advertisements, in print, and on billboards. After the Games and faced with Lewis' new negative image, Nike dropped him. "If you're a male athlete, I think the American public wants you to look macho," said Don Coleman, a Nike representative.[35] "They started looking for ways to get rid of me," Lewis said. "Everyone there was so scared and so cynical they did not know what to do." (Lewis and Nike eventually did split, and Lewis signed an endorsement deal with Mizuno.) Lewis himself would lay the blame on some inaccurate reporting, especially the "Carl bashing," as he put it, typified by a Sports Illustrated article before the Olympics.[37]

At year's end, Lewis was again awarded the top rankings in the 100 m and the long jump and was additionally ranked number one in the 200 m. And for the third year in a row, he was awarded the Athlete of the Year title by Track & Field News.

The Chicago Bulls drafted Lewis in the 1984 NBA Draft as the 208th overall pick, although he had played neither high school nor college basketball. Lewis never played in the NBA. A poll on the NBA's website ranked Lewis second to Lusia Harris, the only woman to be drafted by the NBA, as the most unusual pick in the history of the NBA Draft. Ron Weiss, the head west coast scout of the Bulls, and Ken Passon, the assistant West Coast scout, recommended Lewis because he was the best athlete available.[38] Similarly, though he did not play football in college, Lewis was drafted as a wide receiver in the 12th round of the 1984 NFL Draft by the Dallas Cowboys. He never played in the NFL.[39]

Ben Johnson and the 1987 World Championships

After the Los Angeles Olympics, Lewis continued to dominate track and field, especially in the long jump, in which he would remain undefeated for the next seven years, but others started to challenge his dominance in the 100 m sprint. His low-altitude record had been surpassed by fellow American Mel Lattany with a time of 9.96 s shortly before the 1984 Olympics,[40] but his biggest challenger would prove to be Canadian Ben Johnson, the bronze medalist behind Lewis at the 1984 Olympics. Johnson would beat Lewis once in 1985, but Lewis also lost to others, while winning most of his races. Lewis retained his number one rank that year; Johnson would place second.[10] In 1986, Johnson defeated Lewis convincingly at the Goodwill Games in Moscow, clocking a new low-altitude record of 9.95 s. At year's end, Johnson was ranked number one, while Lewis slipped to number three having lost more races than he won. He even seemed vulnerable in the long jump, an event he did not lose in 1986, or the year before, though he competed sparingly. Lewis ended up ranked second behind Soviet Robert Emmiyan, who had the longest legal jump of the year at 8.61 m (28 ft 2 3⁄4 in).[8]

At the 1987 World Championships in Athletics in Rome, Lewis skipped the 200 m to focus on his strongest event, the long jump, and made sure to take all his attempts. This was not to answer critics from the 1984 long jump controversy; this was because history's second 29 ft long-jumper was in the field: Robert Emmiyan had leaped 8.86 m (29 ft 0 3⁄4 in) at altitude in May, just 4 cm short of Bob Beamon's record.[41] But Emmiyan's best was an 8.53 m (27 ft 11 3⁄4 in) leap that day, second to Lewis's 8.67 m (28 ft 5 1⁄4 in).[42] Lewis cleared 8.60 m (28 ft 2 1⁄2 in) four times. In the 4 × 100 m relay, Lewis anchored the gold-medal team to a time of 37.90 s, the third-fastest of all time.[43]

The event which was most talked about and which caused the most drama was the 100 m final. Johnson had run under 10.00 s three times that year before Rome,[44] while Lewis had not managed to get under the 10.00 s barrier at all. But Lewis looked strong in the heats of the 100 m, setting a Championship record in the semi-final while running into a wind with a 10.03 s effort.[45] In the final, however, Johnson won with a time which stunned observers: 9.83 s, a new world record. Lewis, second with 9.93 s, had tied the existing world record, but that was insufficient.[46]

While Johnson basked in the glory of his achievement, Lewis started to explain away his defeat. He first claimed that Johnson had false-started, then he alluded to a stomach virus which had weakened him, and finally, without naming names, said "There are a lot of people coming out of nowhere. I don't think they are doing it without drugs." He added, "I could run 9.8 or faster in the 100 if I could jump into drugs right away."[47] This was the start of Lewis' calling on the sport of track and field to eliminate the illegal use of performance-enhancing drugs. Cynics noted that the problem had been in the sport for many years, and it only became a cause for Lewis once he was actually defeated. In response to the accusations, Johnson replied "When Carl Lewis was winning everything, I never said a word against him. And when the next guy comes along and beats me, I won't complain about that either".[48]

1988 Summer Olympics

Lewis not only lost the most publicized showdown in track and field in 1987, he also lost his father. When William McKinley Lewis Jr. died, Lewis placed the gold medal he won for the 100 m in 1984 in his hand to be buried with him. "Don't worry," he told his mother. "I'll get another one."[49] Lewis repeatedly referred to his father as a motivating factor for the 1988 season. "A lot happened to me last year, especially the death of my father. That caused me to re-educate myself to being the very best I possibly can be this season," he said, after defeating Johnson in Zürich on August 17.[50]

The 100 m final at the 1988 Summer Olympics was one of the most sensational sports stories of the year and its dramatic outcome would rank as one of the most infamous sports stories of the century.[51] Johnson won in 9.79 s, a new world record, while Lewis set a new American record with 9.92 s. Three days later, Johnson tested positive for steroids, his medal was taken away and Lewis was awarded gold and credited with a new Olympic record.[52]

In the long jump, Robert Emmiyan withdrew from the competition citing an injury, and Lewis' main challengers were rising American long jump star Mike Powell and long-time rival Larry Myricks. Lewis leapt 8.72 m (28 ft 7 1⁄4 in), a low-altitude Olympic best, and none of his competitors could match it. The Americans swept the medals in the event for the first time in 84 years. In the 200 m, Lewis dipped under his Olympic record from 1984, running 19.79 s, but did so in second place to Joe DeLoach, who claimed the new record and Olympic gold in 19.75 s. In the final event he entered, the 4 × 100 m relay, Lewis never made it to the track as the Americans fumbled an exchange in a heat and were disqualified.[53]

A subsequent honor would follow: Lewis eventually was credited with the 100 m world record for the 9.92 s he ran in Seoul. Though Ben Johnson's 9.79 s time was never ratified as a world record, the 9.83 s he ran the year before was. However, in the fallout to the steroid scandal, an inquiry was called in Canada wherein Johnson admitted under oath to long-time steroid use. The IAAF subsequently stripped Johnson of his record and gold medal from the World Championships. Lewis was deemed to be the world record holder for his 1988 Olympic performance and declared the 1987 100 m World Champion. The IAAF also declared that Lewis had also, therefore, twice tied the "true" world record (9.93 s) for his 1987 World Championship performance, and again at the 1988 Zürich meet where he defeated Johnson. However, those times were never ratified as records.[54] From January 1, 1990, Lewis was the world record holder in the 100 m.[55] The record did not last long, as fellow American and University of Houston teammate Leroy Burrell ran 9.90 s on June 14, 1991, to break Lewis's mark.[56] Lewis also permanently lost his ranking as number one for the 200 m in 1988 and for the 100 m in 1989.[28][57] He also lost the top ranking for the long jump in 1990 but was to regain it in 1992.[8]

1991 World Championships: Lewis's greatest performances

Tokyo was the venue for the 1991 World Championships. In the 100 m final, Lewis faced the two men who ranked number one in the world the past two years: Burrell and Jamaican Raymond Stewart.[10] In what would be the deepest 100 meters race ever to that time, with six men finishing in under ten seconds, Lewis not only defeated his opponents, he reclaimed the world record with a clocking of 9.86 s.[58] Though previously a world-record holder in this event, this was the first time he had crossed the line with "WR" beside his name on the giant television screens, and the first time he could savor his achievement at the moment it occurred. He could be seen with tears in his eyes afterwards. "The best race of my life," Lewis said. "The best technique, the fastest. And I did it at thirty."[34] Lewis's world record would stand for nearly three years.[54] Lewis additionally anchored the 4 × 100 m relay team to another world record, 37.50 s, the third time that year he had anchored a 4 × 100 m squad to a world record.

Long jump showdown versus Powell

The 1991 World Championships are perhaps best remembered for the long jump final, considered by some to have been one of greatest competitions ever in any sport.[59] Lewis was up against his main rival of the last few years, Mike Powell, the silver medalist in the event from the 1988 Olympics and the top-ranked long jumper of 1990. Lewis had at that point not lost a long jump competition in a decade, winning the 65 consecutive meets in which he competed. Powell had been unable to defeat Lewis, despite sometimes putting in jumps near world-record territory, only to see them ruled fouls.[60] Or, as with other competitors such as Larry Myricks, putting in leaps which Lewis himself had only rarely surpassed, only to see Lewis surpass them on his next or final attempt.[61][62]

Lewis's first jump was 8.68 m (28 ft 5 1⁄2 in), a World Championship record, and a mark bested by only three others beside Lewis all-time. Powell, jumping first, had faltered in the first round, but jumped 8.54 m (28 ft 0 in) to claim second place in the second round.[63] Lewis jumped 8.83 m (28 ft 11 1⁄2 in), a wind-aided leap, in the third round, a mark which would have won every long jump competition in history except two. Powell responded with a long foul, estimated to be around 8.80 m (28 ft 10 1⁄4 in). Lewis's next jump made history: the first leap ever beyond Bob Beamon's record. The wind gauge indicated the jump was wind-aided, so it could not be considered a record, but it would still count in the competition. 8.91 m (29 ft 2 3⁄4 in) was the greatest leap ever under any condition.[63]

In the next round, Powell responded. His jump was measured as 8.95 m (29 ft 4 1⁄4 in); this time, his jump was not a foul, and with a wind gauge measurement of 0.3 m/s, well within the legal allowable for a record. Powell had not only jumped 4 cm further than Lewis, he had eclipsed the 23-year-old mark set by Bob Beamon and done so at low altitude.[63] Lewis still had two jumps left, though he was now no longer chasing Beamon, but Powell. He leaped 8.87 m (29 ft 1 in), which was a new personal best under legal wind conditions, then a final jump of 8.84 m (29 ft 0 in). He thus lost his first long jump competition in a decade.[64] Powell's 8.95 m (29 ft 4 1⁄4 in) and Lewis's final two jumps still stand as of August 2016 as the top three low altitude jumps ever. The farthest anyone has jumped since under legal conditions is 8.74 m (28 ft 8 in).[65]

Lewis' reaction to what was one of the greatest competitions ever in the sport was to offer acknowledgment of the achievement of Powell.[63] "He just did it," Lewis said of Powell's winning jump. "It was that close, and it was the best of his life."[66] Powell did jump as far or farther on two subsequent occasions, though both were wind-aided jumps at altitude: 8.99 m (29 ft 5 3⁄4 in) in 1992 and 8.95 m (29 ft 4 1⁄4 in) in 1994.[67] Lewis's best subsequent results were two wind-aided leaps at 8.72 m (28 ft 7 1⁄4 in), and an 8.68 m (28 ft 5 1⁄2 in) under legal conditions while in the qualifying rounds at the Barcelona Olympics.[68]

In reference to his efforts at the 1991 World Championships, Lewis said, "This has been the greatest meet that I've ever had."[69] Track and Field News was prepared to go even further than that, suggesting that after these Championships, "It had become hard to argue that he is not the greatest athlete ever to set foot on track or field."[69] Lewis's 1991 outstanding results earned him the ABC's Wide World of Sports Athlete of the Year, an award he shared with gymnastics star Kim Zmeskal.

Final years and retirement

After the heights reached in 1991, Lewis started to lose his dominance in both the sprints and the long jump. Though he anchored a world record 1:19.11 in the rarely run 4 × 200 m relay with the Santa Monica Track Club early in 1992,[70] he failed to qualify for the Olympic team in the 100 m or 200 m. In the latter race, he finished fourth at the Olympic trials behind rising star Michael Johnson who set a personal best of 19.79 s. It was the first time the two had ever met on the track.[71] Lewis did, however, qualify for the long jump, finishing second behind Powell, and was eligible for the 4 × 100 m relay team. At the Games in Barcelona, Lewis jumped 8.67 m (28 ft 5 1⁄4 in) in the first round of the long jump, beating Powell who did a final-round 8.64 m (28 ft 4 in). In the 4 × 100 m relay, Lewis anchored another world record, in 37.40 s, a time which stood for 16 years. He covered the final leg in 8.85 seconds, the fastest officially recorded anchor leg.[72]

Lewis competed at the 4th World Championships in Stuttgart in 1993, but finished fourth in the 100 m,[73] and did not compete in the long jump. He did, however, earn his first World Championship medal in the 200 m, a bronze with his 19.99 s performance.[74] That medal would prove to be his final Olympic or World Championship medal in a running event. Injuries kept Lewis largely sidelined for the next few years, then he made a comeback for the 1996 season.

Lewis qualified for the American Olympic team for the fifth time in the long jump, the first time an American man has done so.[75] At the 1996 Atlanta Olympics, injuries to world-record holder Mike Powell and the leading long-jumper in the world, Iván Pedroso, affected their performances. Lewis, on the other hand, was in good form. Though he did not match past performances, his third-round leap of 8.50 m (27 ft 10 1⁄2 in) won gold by 0.21 m (0 ft 8 1⁄4 in) over second-place James Beckford of Jamaica.[76] He became the third Olympian to win the same individual event four times (and one of only four),[77] joining Danish sailor Paul Elvstrøm and discus thrower Al Oerter of the United States, and later matched by U.S. swimmer Michael Phelps. Additionally, Lewis' nine gold medals tie him for second on the list of multiple Olympic gold medalists with Paavo Nurmi, Larisa Latynina, Mark Spitz, and Usain Bolt behind Phelps.[78]

Lewis' 8.50 m (27 ft 10 1⁄2 in) jump was also officially declared tied with Larry Myricks for the masters record for the 35–39 age group.[79]

Controversy struck when, as Track and Field News put it, "Lewis' attitude in the whole relay hoo-hah a few days later served only to take the luster off his final gold."[76] After Lewis' unexpected long jump gold, it was noted that he could become the athlete with the most Olympic gold medals if he entered the 4 × 100 m relay team. Any member of the American Olympic men's track and field team could be used, even if they had not qualified for the relay event. Lewis said, "If they asked me, I'd run it in a second. But they haven't asked me to run it." He further suggested on Larry King Live that viewers phone the United States Olympic Committee to weigh in on the situation. Lewis had skipped the mandatory relay training camp and demanded to run the anchor leg, which added to the debate. The final decision was to exclude Lewis from the team. Olympic team coach Erv Hunt said, "The basis of their [the relay team's] opinion was 'We want to run, we worked our butts off and we deserve to be here.'"[76] The American relay team finished second behind Canada.[80]

Lewis retired from track and field in 1997.

Stimulant use

In 2003, Wade Exum, the United States Olympic Committee's director of drug control administration from 1991 to 2000, gave copies of documents to Sports Illustrated which revealed that some 100 American athletes failed drug tests from 1988 to 2000, arguing that they should have been prevented from competing in the Olympics but were nevertheless cleared to compete. Before showing the documents to Sports Illustrated Exum tried to use them in a lawsuit against USOC, accusing the organization of racial discrimination and wrongful termination against him and cover-up over the failed tests. His case was shortly dismissed by the Denver federal Court for lack of evidence. The USOC claimed his case "baseless" as he himself was the one in charge of screening the anti-doping test program of the organization and clarifying that the athletes were cleared according to the rules.[81][82]

Among the names of the athletes was Lewis. It was revealed that he tested positive three times at the 1988 Olympics Trials for minimum amounts of pseudoephedrine, ephedrine, and phenylpropanolamine, banned stimulants and bronchodilators also found in cold medication and due to the rules his case could lead to disqualification from the Seoul Olympics and from competition for six months. The levels of the combined stimulants registered in the separate tests were 2 ppm, 4 ppm and 6 ppm.[81]

Lewis defended himself claiming he accidentally consumed the banned substances. After the supplements he was taking had been analyzed to prove his claims the USOC accepted his claim of inadvertent use, since a dietary supplement he ingested was found to contain "Ma huang", the Chinese name for Ephedra (ephedrine is known to help weight loss).[81] Fellow Santa Monica Track Club teammates Joe DeLoach and Floyd Heard were also found to have the same banned stimulants in their systems, and were cleared to compete for the same reason.[83][84]

The highest level of the stimulants Lewis recorded was 6 ppm, which was regarded as a positive test in 1988 but is now regarded as negative test. The acceptable level has been raised to ten parts per million for ephedrine and twenty-five parts per million for other substances.[81][85] According to the IOC rules at the time, positive tests with levels lower than 10 ppm were cause of further investigation but not immediate ban. Neal Benowitz, a professor of medicine at UC San Francisco who is an expert on ephedrine and other stimulants, agreed that "These [levels] are what you'd see from someone taking cold or allergy medicines and are unlikely to have any effect on performance."[81]

Following Exum's revelations the IAAF acknowledged that at the 1988 Olympic Trials the USOC indeed followed the correct procedures in dealing with eight positive findings for ephedrine and ephedrine-related compounds in low concentration. The federation also reviewed in 1988 the relevant documents with the athletes' names undisclosed and stated that "the medical committee felt satisfied, however, on the basis of the information received that the cases had been properly concluded by the USOC as 'negative cases' in accordance with the rules and regulations in place at the time and no further action was taken".[86][87]

"Carl did nothing wrong. There was never intent. He was never told 'you violated the rules'" said Martin D. Singer, Lewis' lawyer, who also said that Lewis had inadvertently taken the banned stimulants in an over-the-counter herbal remedy.[88] In an interview dating back April 2003 Carl Lewis agreed that he tested positive three times in 1988 but he was let off as that was the normal practice in those times.[89] "The only thing I can say is I think it's unfortunate what Wade Exum is trying to do," said Lewis. "I don't know what people are trying to make out of nothing because everyone was treated the same, so what are we talking about? I don't get it."[90]

Achievements and honors

- Lewis is the only man to defend an Olympic long jump title.

- Outdoors, Lewis jumped 14 of the 20 furthest ancillary jumps of all time. (Ancillary marks are those which are valid, but were not the furthest in a series.)[91]

Personal best marks

- 100 m: 9.86 s (August 1991, Tokyo)

- 200 m: 19.75 s (June 1983, Indianapolis)

- Long jump: 8.87 m (29 ft 1 in) 1991, w 8.91 m (29 ft 2 3⁄4 in) 1991 (both in Tokyo)

- 4 × 100 m relay: 37.40 s (United States – Marsh; Burrell; Mitchell; Lewis – August 1992, Barcelona)

- 4 × 200 m relay: 1:18.68 min (Santa Monica Track Club – Marsh; Burrell; Heard; Lewis – 1994; (former world record)

Honors

In 1999, Lewis was voted "Sportsman of the Century" by the International Olympic Committee,[92] elected "World Athlete of the Century" by the International Association of Athletics Federations[92] and named "Olympian of the Century" by Sports Illustrated.[93] In 2000 his alma mater University of Houston named the Carl Lewis International Complex after him.

In 2016, Lewis was Inducted into the Texas Track and Field Coaches Association Hall of Fame.[94]

Career outside athletics

Film and television

Lewis has appeared in numerous films and television productions. Among them, he played himself in cameos in Perfect Strangers, Speed Zone, Alien Hunter and Material Girls. Lewis made an appearance on The Weakest Link. Additionally, he played Stu in the made-for-TV movie Atomic Twister.

In 2011, Lewis appeared in the short documentary Challenging Impossibility which features the feats of strength demonstrated by the late spiritual teacher and peace advocate Sri Chinmoy.[95]

Lewis appeared in the movie The Last Adam (2006).

Bid for New Jersey State Senate

On April 11, 2011, Lewis filed petitions to run as a Democrat for New Jersey Senate in the state's 8th legislative district in Burlington County.[96] Two weeks later he was disqualified by Lieutenant Governor Kim Guadagno, a Republican acting in her role as the secretary of state, who decided he did not meet the state's requirement that Senate candidates live in New Jersey for four years.[97] Lewis appealed her decision to the Third Circuit Court of Appeals; the court initially granted his appeal but a few days later the court reversed itself and Lewis withdrew his name.[98][99]

Personal life

Lewis is a vegan. Lewis credits his outstanding 1991 results in part to the vegan diet he adopted in 1990, when he was in his late twenties. He has claimed it is better suited to him because he can eat a larger quantity without affecting his athleticism[100][101] and he believes that switching to a vegan diet can lead to improved athletic performance.

See also

- List of vegans

- List of multiple Olympic gold medalists at a single Games

- List of multiple Olympic gold medalists in one event

- 100 metres at the World Championships in Athletics

References

- ↑ "Carl Lewis". sports-reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved January 21, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gleason, David (December 1980). "T&FN Interview: Carl Lewis" (PDF). Track & Field News. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- 1 2 "William Lewis, Track Coach and Father of Olympic Star". The New York Times. Associated Press. May 7, 1987. Retrieved January 30, 2009.

- ↑ "Carol Lewis". Olympics at Sports-Reference.com.

- ↑ "Long Jump Result – 1st IAAF World Championships in Athletics – iaaf.org". iaaf.org.

- ↑ Strauss, Robert (December 2, 2001). "WORTH NOTING; Carl Lewis Takes Honors, But Not at His Home Track". The New York Times. Retrieved March 31, 2008.

- ↑ "T&FN Boys' Long Jump All-Americas". trackandfieldnews.com.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Men's World Rankings by Athlete: Long Jump" (PDF). trackandfieldnews.com. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- ↑ "Olympic Boycott Games". gbrathletics.com.

- 1 2 3 4 "World Rankings by Athlete: 100m" (PDF). trackandfieldnews.com. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- ↑ Track and Field News, January 1982; vol. 34, #12, p. 46

- 1 2 "Olympic world records may be wrong". Weeklyscientist.com. Archived from the original on January 29, 2005. Retrieved June 9, 2015.

- ↑ Track and Field News, July 1982, vol. 35 #6, p. 61

- ↑ Track and Field News, July 1981, vol. 34 #6, p. 12

- ↑ "The Sullivan Award Winner". Aausullivan.org. July 1, 1961. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- ↑ "Beamon made sport's greatest leap". Espn.go.com. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- ↑ Track and Field News, January 1983, vol. 35 #12, p. 45

- ↑ Track and Field News, August 1982, vol. 35, #6, p.28–29

- ↑ "1st IAAF World Championships in Athletics > Long Jump – men > Final". IAAF. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- ↑ "1st IAAF World Championships in Athletics > 100 meters – men > Final". IAAF. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- ↑ "1st IAAF World Championships in Athletics > 200 meters – men > Final". IAAF. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- 1 2 Track and Field News August 1983, vol. 36, #7, p.4, 9

- ↑ See the end of the race in this video on YouTube

- ↑ "1st IAAF World Championships in Athletics > 4x100 meters Relay – men > Final". IAAF. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- ↑ Track and Field News, June 1983, vol. 36 #5, p. 6,7

- ↑ Track and Field News, January 1984, vol. 36 #12, p. 22

- ↑ Track and Field News, January 1984, vol. 36 #12, p. 48

- 1 2 "World Rankings — Men's 200" (PDF). trackandfieldnews.com. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

- ↑ "T&FN's WORLD MEN'S ATHLETES OF THE YEAR" (PDF). Retrieved June 10, 2015.

- 1 2 "Carl Lewis – 100m". olympic.org.

- ↑ "Carl Lewis. New Gold Miner". Track and Field News. 37 (8): 47. September 1984.

- ↑ Corry, John (August 9, 1984). "TV Review; ABC'S Coverage of the Olympics". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Carl Lewis". usatf.com.

- 1 2 "ESPN Classic – King Carl had long, golden reign". Espn.go.com. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- 1 2 The Runner Stumbles p2, The New York Times, July 19, 1992. Accessed February 20, 2008.

- ↑ The Dallas Morning News (January 1, 1996). "APSE | Associated Press Sports Editors". Apse.dallasnews.com. Archived from the original on March 30, 2012. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- ↑ The Runner Stumbles p3, The New York Times, July 19, 1992. Accessed February 20, 2008.

- ↑ "Poll Result Display". Nba.com. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- ↑ "NFL Draft History: Full Draft". Nfl.com. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- ↑ Track and Field News, January/February 1986, vol. 39 #1–2, p. 14

- ↑ Track and Field News, July 1987, vol. 40 #7, p. 34

- ↑ "2nd IAAF World Championships in Athletics > Long Jump – men > Final result". IAAF. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- ↑ "2nd IAAF World Championships in Athletics > 4x100 meters Relay – men > Final result". IAAF. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- ↑ Track and Field News, January 1988, vol. 41, #1, p. 20

- ↑ "2nd IAAF World Championships in Athletics > 100 meters – men > Heats results". IAAF. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- ↑ Track and Field News, November 1987, vol. 40 #11, p. 9

- ↑ Track and Field News, December 1987, vol. 40, #12, p. 28

- ↑ Slot, Owen (September 22, 2003). "Ambition naivety and tantalising prospect of inheriting the world". The Times. London. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ↑ "ESPN Classic – More Info on Carl Lewis". Espn.go.com. November 19, 2003. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- ↑ Track and Field News, October 1988, vol. 41, #10, p. 25

- ↑ "St. Petersburg Times: Top 100 sports stories". Sptimes.com. April 30, 1993. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- ↑ Track and Field News, November 1988, vol. 41 #11, p. 10–11

- ↑ "Athletics Results – Seoul 1988 – Olympic Medals". olympic.org.

- 1 2 "12th IAAF World Championships In Athletics: IAAF Statistics Handbook. Berlin 2009." (PDF). Monte Carlo: IAAF Media & Public Relations Department. 2009. pp. Pages 546, 547. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 6, 2009. Retrieved August 7, 2009.

- ↑ Track and Field News, November 1989, vol. 42, #11, p. 37

- ↑ "Leroy Burrell Bio – University of Houston Athletics :: UH Cougars :: Official Athletic Site". uhcougars.com.

- ↑ "World Rankings — Men's 100" (PDF).

- ↑ Track and Field News, November 1991, vol. 44, #11, p. 9

- ↑ "2001 Has A Lot To Live Up To". BBC News. July 27, 2001. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ↑ "Mike Powell". Usatf.com. Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- ↑ Track and Field News, September 1988, vol. 41 #9, p. 18–19

- ↑ Track and Field News, August 1991, vol. 44 #8, p. 14–15

- 1 2 3 4 "USATF – News". usatf.org.

- ↑ Track and Field News, November 1991, vol. 44, #11, p. 30–31

- ↑ "Long Jump All Time List". IAAF. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- ↑ "29–4½! Soaring Powell Conquers Beamon's Record," The New York Times, August 31, 1991

- ↑ "Mike POWELL – U.S.A. - Long Jump world record and two World Championship golds.". Sporting Heroes.

- ↑ "Carl Lewis Career Facts & Statistics -LEWIS' 28 FOOT JUMPS". Web.archive.org. October 10, 2002. Archived from the original on October 10, 2002. Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- 1 2 Track and Field News, November 1991, vol. .44, #11, p. 8

- ↑ Track and Field News, June 1992, vol. 45, #6, p.4–5

- ↑ Track and Field News, August 1992, vol. 45, #6, p. 8

- ↑ "USA Men's 4x100m". olympic.org.

- ↑ "4th IAAF World Championships in Athletics > 100 meters – men > Final". IAAF. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- ↑ "4th IAAF World Championships in Athletics > 200 meters – men > Final". IAAF. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- ↑ Track and Field News, September 1996, vol. 49, #9, p. 18

- 1 2 3 Track and Field News October 1996, vol. 49, #10, p. 36

- ↑ "International Olympic Committee – Athletes". Olympic.org. August 13, 2004. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- ↑ Wallechinsky, David; Jaime Loucky (2008). The Complete Book of the Olympics: 2008 Edition. Aurum Press. p. 702. ISBN 978-1-84513-330-6.

- ↑ "Records Outdoor Men". World-masters-athletics.org. March 27, 2012. Archived from the original on September 3, 2011. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- ↑ "Athletics Results – Atlanta 1996 – Olympic Medals". olympic.org.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Abrahamson, Alan (April 23, 2003). "Just a dash of drugs in Lewis, DeLoach". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ "Anti-Doping Official Says U.S. Covered Up". The New York Times. April 17, 2003.

- ↑ "Scorecard". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved October 10, 2012.

- ↑ "Carl Lewis's positive test covered up". Smh.com.au. April 18, 2003. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- ↑ Wallechinsky and Loucky, The Complete Book of the Olympics (2012 edition), page 61

- ↑ "IAAF: USOC followed rules over dope tests". April 30, 2003. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014.

- ↑ Abrahamson, Alan (May 1, 2003). "USOC's Actions on Lewis Justified by IAAF". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ "This idol has feet of clay, after all". Sportstar. 26 (18). May 3–9, 2003. Archived from the original on February 22, 2007.

- ↑ Duncan Mackay (April 24, 2003). "Lewis: 'Who cares I failed drug test?' ". theguardian.com. Retrieved September 9, 2013.

- ↑ "Lewis dismisses drugs claims". BBC News. April 23, 2003. Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- ↑ "Men's long jump". www.alltime-athletics.com. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- 1 2 "IAAF Hall of Fame: Carl Lewis". iaaf.org. IAAF. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- ↑ "Sports Illustrated honors world's greatest athletes". CNN. December 3, 1999. Archived from the original on January 4, 2014. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ↑ "Rice Legends to be Inducted Into TTFCA Hall of Fame Friday". Rice University. January 7, 2016. Retrieved October 2, 2016.

- ↑ Kilgannon, Corey (April 25, 2011). "A Monument to Strength as a Path to Enlightenment". New York Times. Retrieved April 25, 2011.

- ↑ Max Pizarro. "Track Olympian Lewis launches LD 8 Senate campaign". New Jersey News, Politics, Opinion, and Analysis. Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- ↑ Angela, Delli Santi (April 26, 2011). "Guadagno disqualifies Olympian Carl Lewis from running for state Senate". The Press of Atlantic City. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ↑ Warner, Dave (September 29, 2011). "Olympian Carl Lewis quits state senate race in New Jersey". Reuters. Retrieved September 23, 2011.

- ↑ Schilken, Chuck (January 21, 2014). "Carl Lewis: Chris Christie tried to intimidate me during Senate bid". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- ↑ "EarthSave International". Earthsave.org. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- ↑ "» Athletic Anti-Nutrition: What a Vegan Diet Really Did for Carl Lewis The Bulletproof Executive". Bulletproofexec.com. February 29, 2012. Retrieved August 1, 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carl Lewis. |

- Official website

- Carl Lewis profile at IAAF

- Olympiad Results for Carl Lewis

- Carl Lewis at the Internet Movie Database