Cariban languages

| Cariban | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution: | Mostly within north-central South America, with extensions in the southern Caribbean and in Central America. |

| Linguistic classification: |

|

| Glottolog: | cari1283[1] |

|

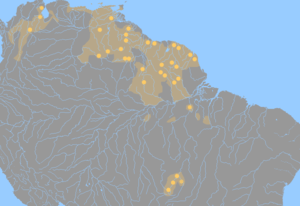

Present location of Cariban languages, c. 2000, and probable extent in the 16th century. | |

The Cariban languages are an indigenous language family of South America. They are widespread across northernmost South America, from the mouth of the Amazon River to the Colombian Andes, but also appear in central Brazil. Cariban languages are relatively closely related, and number two to three dozen, depending on what is considered a dialect. Most are still spoken, though often by only a few hundred speakers; the only one with more than a few thousand is Macushi, with 30,000. The Cariban family is well known in the linguistic world partly because Hixkaryana has a default object–verb–subject word order, previously thought not to exist in human language.

Some years prior to the arrival of the first Spanish explorers, Caribs invaded and occupied the Lesser Antilles, killing, displacing or assimilating the Arawaks who inhabited the islands. The resulting language was Carib in name but largely Arawak in substance. This was due to invading Carib men killing Arawak men and taking Arawak wives, who then passed their language on to the children. For a time, Arawak was spoken by women and children and Carib by adult men, but the situation was unstable. As each generation of Carib-Arawak boys reached adulthood, they acquired less Carib, until only basic vocabulary and a few grammatical elements were left. This "Island Carib" became extinct in the Lesser Antilles in the 1920s, but survives in the form of Garífuna, or "Black Carib", in Central America. The gender distinction has dwindled to only a handful of words. Dominica is the only island in the eastern Caribbean to retain some of its pre-Columbian population—the Carib Indians—about 3,000 of whom live on the island's east coast.

Family division

The Cariban languages are closely related, and in many cases where a language is more distinct, this is due to influence from neighboring languages rather than an indication that it is not closely related. Kaufman 2007 says, "Except for Opon, Yukpa, Pimenteira and Palmela (and possibly Panare), the Cariban languages are not very diverse phonologically and lexically (though more so than Romance, for example)."

Previous classifications

Good data has been collected around ca. 2000 on most Cariban languages; classifications prior to that time (including Kaufman 2007, which relies on them) are unreliable. Several such classifications are seen; the one shown here divides Cariban into seven branches. A traditional geographic classification into northern and southern branches is cross referenced with (N) or (S) after each language.[2]

- Galibi [Kaliña] (N)

- Guiana Carib (Taranoan):

- North Amazonian Carib:

- Yawaperi: Atruahí [Atrowari, Waimiri] (N)

- Pemong: Macushi–Pemon [Arekuna], Akawaio–Patamona (= Kapong, Ingariko) (N)

- Paravilyana: Pawishiana (†)

- Kaufman breaks this up into its constituent branches, adding Purukotó (†) to Pemong; Boanarí (†) to Atruahí; Paravilyana (†) and Sapará (†) to Pawishiana

- Central Carib:

- South Amazonian Carib:

- Yukpa:

- Panare (N)

- Opon [Opón-Karare] (†)

Unclassified: Pimenteira (†), Palmela (†).

The extinct Patagón de Perico language of northern Peru also appears to have been a Cariban language, perhaps close to Carijona. Yao is so poorly attested that Gildea believes it may never be classified.

Gildea (2012)

As of Gildea (2012), there had not yet been time to fully reclassify the Cariban languages based on the new data. The list here is therefore tentative, though an improvement over the one above; the most secure branches are listed first, and only two of the extinct languages are addressed.[3]

- Parukotoan

- Katxúyana (Shikuyana, (†) Warikyana)

- Waiwai: Waiwai (Wabui, Tunayana), Hixkaryana

- Pekodian

- Venezuelan Carib

- Nahukwa: Kuikúro, Kalapalo

- Guianan Carib

Unclassified:

- Apalaí

- Waimirí Atroarí

- Yukpa: Yukpa, Japréria

Genetic relations

The Cariban languages share irregular morphology with the Ge and Tupi families, and Ribeiro connects them all in a Je–Tupi–Carib family. Meira, Gildea, & Hoff (2010) note that likely morphemes in proto-Tupian and proto-Cariban are good candidates for being cognates, but that work so far is insufficient to make definitive statements.

See also

- List of Spanish words of Indigenous American Indian origin

- Arawak peoples

- Arawakan languages

- Carib language

- Taíno language

- Garifuna language

References

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Cariban". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Desmond Derbyshire, 1999. "Carib". In Dixon & Aikhenvald, eds., The Amazonian Languages. CUP.

- ↑ Spike Gildea, 2012, "Linguistic studies in the Cariban family", in Campbell & Grondona, eds, The Indigenous Languages of South America: A Comprehensive Guide

External links

- Etnolinguistica.Org: online resources on native South American languages

- Ka'lina (Carib) Vocabulary List (from the World Loanword Database)