Capernaum

| כְּפַר נַחוּם | |

_on_the_shore_of_the_Lake_of_Galilee%2C_Northern_Israel.jpg) Capernaum synagogue | |

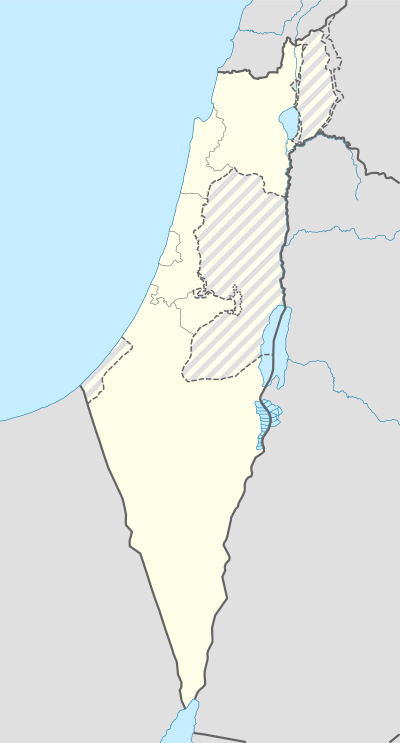

Shown within Israel | |

| Location | Northern District, Israel |

|---|---|

| Region | Sea of Galilee |

| Coordinates | 32°52′52″N 35°34′30″E / 32.88111°N 35.57500°ECoordinates: 32°52′52″N 35°34′30″E / 32.88111°N 35.57500°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Cultures | Hasmonean, Roman |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | Ruined |

Capernaum (/kəˈpɜːrniəm/ kə-PUR-nee-əm; Hebrew: כְּפַר נַחוּם, Kfar Nahum; Arabic: كفر ناحوم, meaning "Nahum's village" in both languages) was a fishing village established during the time of the Hasmoneans, located on the northern shore of the Sea of Galilee.[1] It had a population of about 1,500.[2] Archaeological excavations have revealed two ancient synagogues built one over the other. A house turned into a church by the Byzantines is said to be the home of Saint Peter.

The village was inhabited continuously from the 2nd century BCE to the 11th century CE, when it was abandoned sometime before the Crusader conquest.[3] This includes the re-establishment of the village during the Early Islamic period soon after the 749 earthquake.[3]

Etymology

Kfar Nahum, the original name of the small town, means "Nahum's village" in Hebrew, but apparently there is no connection with the prophet named Nahum. In the writings of Josephus, the name is rendered in Greek as Kαφαρναούμ, Kapharnaum (Tzaferis, 1989), and Κεφαρνωκόν, "Kepharnōkon";[4] the New Testament uses Kapharnaum in some manuscripts, and Kαπερναούμ, Kapernaum, in others. In Arabic, it is called Talhum, and it is assumed that this refers to the ruin (tell) of Hum (perhaps an abbreviated form of Nahum) (Tzaferis, 1989).

New Testament

_-_James_Tissot_-_overall.jpg)

The town is cited in all four gospels (Matthew 4:13, 8:5, 11:23, 17:24, Mark 1:21, 2:1, 9:33, Luke 4:23, 31,7:1, 10:15, John 2:12, 4:46, 6:17, 24,59) where it was reported to have been near the hometown of the apostles Simon Peter, Andrew, James and John, as well as the tax collector Matthew. One Sabbath, Jesus taught in the synagogue in Capernaum and healed a man who was possessed by an unclean spirit (Luke 4:31–36 and Mark 1:21–28). This story is notable for being the only one common between the gospels of Mark and Luke, but not contained in the Gospel of Matthew (see Synoptic Gospels for more literary comparison between the gospels). Afterwards, he healed Simon Peter's mother-in-law of a fever (Luke 4:38-39). According to Luke 7:1–10, it is also the place where Jesus healed the servant of a Roman centurion who had asked for his help. Capernaum is also mentioned in Matthew 9:1–8, Mark 2:1–12, and Luke 5:17–26 as the location of the famous healing of the paralytic lowered through the roof to reach Jesus.

According to the Synoptic Gospels, Jesus selected this town as the center of his public ministry in Galilee after he left the small mountainous hamlet of Nazareth (Matthew 4:12–17). He also formally cursed the city, saying "you will be thrown down to Hades!" (Matthew 11:23) because of their lack of faith in him as the Messiah.

History

Archaeological evidence demonstrates that the town was established in the 2nd century BC during the Hasmonean period, when a number of new fishing villages sprung up around the lake. The site had no defensive wall and extended along the shore of the nearby lake (from east to west). The cemetery zone is found 200 meters north of the synagogue, which places it beyond the inhabited area of the town. It extended 3 kilometers to Tabgha, an area which appears to have been used for agricultural purposes, judging by the many oil and grain mills which were discovered in the excavation. Fishing was also a source of income; the remains of another harbor were found to the west of that built by the Franciscans.

No sources have been found for the belief that Capernaum was involved in the bloody Jewish revolts against the Romans, the First Jewish-Roman War (AD 66–73) or Bar Kokhba's revolt (132–135), although there is reason to believe that Josephus, one of the Jewish generals during the earlier revolt, was taken to Capernaum (which he called Κεφαρνωκὸν, "Kapharnakos") after a fall from his horse in nearby Bethsaida.[4][5]

Josephus referred to Capernaum as a fertile spring. He stayed the night there after bruising his wrist in a riding accident.[5] During the first Jewish revolt of 66–70 Capernaum was spared as it didn't have to be occupied by force by the Romans.

Archaeology

In 1838, American explorer Edward Robinson discovered the ruins of ancient Capernaumm. In 1866, British Captain Charles William Wilson identified the remains of the synagogue, and in 1894, Franciscan Friar Giuseppe Baldi of Naples, the Custodian of the Holy Land, was able to recover a good part of the ruins from the Bedouins. The Franciscans raised a fence to protect the ruins from frequent vandalism, and planted palms and eucalyptus trees brought from Australia to create a small oasis for pilgrims. They also built a small harbor. These labors were directed by Franciscan Virgilio Corbo.

The most important excavations began in 1905 under the direction of Germans Heinrich Kohl and Carl Watzinger. They were continued by Franciscans Fathers Vendelin von Benden (1905–1915) and Gaudenzio Orfali (1921–1926). The excavations resulted in the discovery of two public buildings, the synagogue (which was partially restored by Fr Orfali), and an octagonal church. Later, in 1968, excavation of the western portion of the site—the portion owned by the Franciscans—was restarted by Corbo and Stanislao Loffreda, with the financial assistance of the Italian government. During this phase, the major discovery was of a house which is claimed to be St. Peter's house in a neighborhood of the town from the 1st century AD. These excavations have been ongoing, with some publication on the Internet as recently as 2003.[6]

The excavations revealed that the site was established at the beginning of the Hasmonean period, roughly in the 2nd century BC, and abandoned in the 11th century.

The eastern half of the site, where the Church of the Seven Apostles stands and owned by an Orthodox monastery, was surveyed and partially excavated under the direction of Vasilios Tzaferis. This section has uncovered the village from the Byzantine and Early Arab periods. Features include a pool apparently used for the processing of fish, and a hoard of gold coins. (Tzaferis, 1989).

The layout of the town was quite regular. On both sides of an ample north-south main street arose small districts bordered by small cross-sectional streets and no-exit side-streets. The walls were constructed with coarse basalt blocks and reinforced with stone and mud, but the stones (except for the thresholds) were not dressed and mortar was not used.

The most extensive part of the typical house was the courtyard, where there was a circular furnace made of refractory earth, as well as grain mills and a set of stone stairs that led to the roof. The floors of the houses were cobbled. Around the open courtyard, modest cells were arranged which received light through a series of openings or low windows (Loffreda, 1984).

Given the coarse construction of the walls, there was no second story to a typical home, and the roof would have been constructed of light wooden beams and thatch mixed with mud. This, along with the discovery of the stairs to the roof, recalls the biblical story of the Healing of the Paralytic: "And when they could not come nigh unto him for the press, they uncovered the roof where he was: and when they had broken it up, let down the bed wherein the sick of the palsy lay." (Mark 2:4) With the type of construction seen in Capernaum, it would not have been difficult to raise the ceiling by the courtyard stairs and to remove a part to allow the bed to be brought down to where Jesus stood.

A study of the district located between the synagogue and the octagonal church showed that several families lived together in the patriarchal style, communally using the same courtyards and doorless internal passages. The houses had no hygienic facilities or drainage; the rooms were narrow. Most objects found were made of clay: pots, plates, amphoras, and lamps. Fish hooks, weights for fish nets, striker pins, weaving bobbins, and basalt mills for milling grain and pressing olives were also found (Loffreda, 1974).

As of the 4th century, the houses were constructed with good quality mortar and fine ceramics. This was about the time that the synagogue now visible was built. Differences in social class were not noticeable. Buildings constructed at the founding of the town continued to be in use until the time of the abandonment of the town.

House of Peter

One block of homes, called by the Franciscan excavators the sacra insula or "holy insula" ("insula" refers to a block of homes around a courtyard) was found to have a complex history. Located between the synagogue and the lake shore, it was found near the front of a labyrinth of houses from many different periods. Three principal layers have been identified:

- A group of private houses built around the 1st century BC which remained in use until the early 4th century.

- The great transformation of one of the homes in the 4th century.

- The octagonal church in the middle of the 5th century.

The excavators concluded that one house in the village was venerated as the house of Peter the fisherman as early as the mid-1st century, with two churches having been constructed over it (Loffreda, 1984).

1st century

The city's basalt houses are grouped around two large courtyards, one to the north and the other to the south. One large room in particular, near the east side and joining both courtyards, was especially large (sides about 7.5 meters long) and roughly square. An open space on the eastern side contained a brick oven. A threshold which allowed crossing between the two courtyards remains well-preserved to this day.

Beginning in the latter half of the 1st century AD, this house displayed markedly different characteristics than the other excavated houses. The rough walls were reworked with care and were covered with inscriptions; the floor was covered with a fine layer of plaster. Furthermore, almost no domestic ceramics are recovered, but lamps abound. One explanation suggested for this treatment is that the room was venerated as a religious gathering place, a domus-ecclesia or house church, for the Christian community. (Loffreda, 1984) This suggestion has been critiqued by several scholars, however. In particular, where excavators had claimed to find graffiti including the name of Peter, others have found very little legible writing (Strange and Shanks, 1982). Others have questioned whether the space is actually a room; the paved floor, the large space without supports, and the presence of a cooking space have prompted some to note that these are more consistent with yet another courtyard (Freyne, 2001).

4th-century transformation

In this period, the sacra insula acquired a new appearance. First, a thick-walled, slightly trapezoidal enclosure was built surrounding the entire insula; its sides were 27–30 meters long. Made of plaster, they reached a height of 2.3 meters on the north side. It had two doors, one in the southwest corner and the other in the northeast corner. Next, although there is evidence that the private houses remained in use after the transformation, the one particular room that had before been treated differently was profoundly altered and expanded. A central archway was added to support a roof and the north wall was strengthened with mortar. New pavement was installed, and the walls and floor were plastered. (Loffreda, 1974) This structure remained until the middle of the 5th century when the sacra insula was dismantled and replaced with a larger basilica.

Octagonal 5th-century church

The 5th-century church consists of a central octagon with eight pillars, an exterior octagon with thresholds still in situ, and a gallery or portico that leads both into the interior of the church as well as into a complex of associated buildings to the east, a linkage achieved via a short passageway. Later, this passage was blocked and an apse with a pool for baptism was constructed in the middle of the east wall. From this wall ascended two stairs on either side of the baptistery, and the excess water from the rite would have escaped along this path. The Byzantines, upon constructing the new church, placed the central octagon directly on top of the walls of St. Peter's house with the aim of preserving its exact location, although none of the original house was visible any longer, as the walls had been torn down and the floor covered in mosaics.

In the portico, the pattern of the mosaic was purely geometric, with four rows of contiguous circles and small crosses. In the zone of the external octagon, the mosaics represented plants and animals in a style similar to that found in the Basilica of the Feeding of the Five Thousand, in Tabgha. In the central octagon, the mosaic was composed of a strip of calcified flowers, of a field of schools of fish with small flowers, and of a great circle with a peacock in the center.

The Memorial (1990)

The so-called Memorial is a modern shrine built above the excavated remains of the ancient house and the Byzantine octagonal church, and dedicated in 1990.[7] The disk-shaped structure stands on concrete stilts, ensuring visibility to the venerated ancient building. Additionally, a glass floor located at the centre of the church allows direct view of the excavated remains below.

Synagogue

The ruins of this building, among the oldest synagogues in the world, were identified by Charles William Wilson. The large, ornately carved, white building stones of the synagogue stood out prominently among the smaller, plain blocks of local black basalt used for the town's other buildings, almost all residential. The synagogue was built almost entirely of white blocks of calcareous stone brought from distant quarries.

The building consists of four parts: the praying hall, the western patio, a southern balustrade and a small room at the northwest of the building. The praying hall measured 24.40 m by 18.65 m, with the southern face looking toward Jerusalem.

The internal walls were covered with painted plaster and fine stucco work found during the excavations. Watzinger, like Orfali, believed that there had been an upper floor reserved for women, with access by means of an external staircase located in the small room. But this opinion was not substantiated by the later excavations of the site.

The synagogue appears to have been built around the 4th or 5th century. Beneath the foundation of this synagogue lies another foundation made of basalt, and Loffreda suggests that this is the foundation of a synagogue from the 1st century, perhaps the one mentioned in the Gospels (Loffreda, 1974). Later excavation work was attempted underneath the synagogue floor, but while Loffreda claimed to have found a paved surface, others are of the opinion that this was an open, paved market area.

The ancient synagogue has two inscriptions, one in Greek and the other in Aramaic, that commemorates the benefactors that helped in the construction of the building. There are also carvings of five- and six-pointed stars and of palm trees.

In 1926, the Franciscan Father Gaudenzio Orfali began the restoration of the synagogue. The work was interrupted by his death in a car accident in 1926 (which is commemorated by a Latin inscription carved onto one of the synagogue's columns), and was continued by Virgilio Corbo beginning in 1976.

Papal visit

In March 2000, John Paul II visited the ruins of Capernaum during his visit to Israel.[8]

See also

- Archaeology of Israel

- Monastery of the Holy Apostles, the Greek Orthodox church and monastery at Capernaum

- National parks of Israel

- New Testament places associated with Jesus

- Oldest synagogues in the world

- Sea of Galilee Boat

- Tourism in Israel

- Woes to the unrepentant cities, pronounced by Jesus and which include Capernaum

References

- ↑ Freedman, DN 2000, Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible, Amsterdam University Press

- ↑ Reed, JL, Archaeology and the Galileen Jesus: A Reexamination of the Evidence (Harrisburg: Trinity Press International, 2000)

- 1 2 Gideon Avni (2014). The Byzantine-Islamic Transition in Palestine: An Archaeological Approach. Oxford Studies in Byzantium. Oxford University Press. pp. 88–89. ISBN 9780199684335.

- 1 2 Josephus, Vita 72, original text in Greek

- 1 2 Josephus, Vita, English translation

- ↑ http://www.christusrex.org/www1/ofm/sbf/arch/Capharnaum2003.html

- ↑ Capharnaum, the Town of Jesus: The insula sacra. ChristusRex.org, (c)2001

- ↑ Papal Visit to Israel: Itinerary

Further reading

- Sean Freyne, "A Galilean Messiah?," Studia Theologica 55 (2001), 198–218. Contains an analysis of the singled-out 1st-century AD house as a courtyard rather than a room or house.

- Loffreda, Stanislao. Cafarnao. Vol. II. La Ceramica. Jerusalem: Franciscan Printing Press, 1974. Technical publication (in original Italian) of the western site.

- Loffreda, Stanislao. Recovering Capharnaum. Jerusalem: Edizioni Custodia Terra Santa, 1984. ASIN B0007BOTZY. Non-technical English summary of the excavations on the western (Franciscan) portion of the site.

- Jerome Murphy-O'Connor, Oxford Archaeological Guides: The Holy Land (Oxford, 1998), 217–220. ASIN 0192880136.

- James F. Strange and Hershel Shanks, "Has the House Where Jesus Stayed in Capernaum Been Found?," Biblical Archaeology Review 8, 6 (Nov./Dec., 1982), 26–37. Critique of the domus-ecclesia claims.

- Tzaferis, Vassilios. Excavations at Capernaum, 1978–1982. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns, 1989. ISBN 0-931464-48-X. Overview publication of the dig on the eastern portion of the site.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Capernaum. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Capernaum. |

- Strong's G2584

- Capharnaum – The town of Jesus – Franciscan Cyberspot

- Capernaum – information from the Israeli government

- Capernaum – Sacred Destinations (includes 38 photos)

- Images of Capernaum

- Article by Dr. Zeev Goldmann