Flag of Canada

| |

| Name | Canadian flag, The Maple Leaf, l'Unifolié |

|---|---|

| Use | National flag, civil and state ensign |

| Proportion | 1:2 |

| Adopted | February 15, 1965 |

| Design | A vertical triband of red (hoist-side and fly-side) and white (double width) with the red maple leaf centred on the white band. |

| Designed by | George F.G. Stanley |

The flag of Canada, often referred to as the Canadian flag, or unofficially as the Maple Leaf and l'Unifolié (French for "the one-leafed"), is a national flag consisting of a red field with a white square at its centre in the ratio of 1:2:1, in the middle of which is featured a stylized, red, 11-pointed maple leaf charged in the centre.[1] It is the first ever specified by law for use as the country's national flag.

In 1964, Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson formed a committee to resolve the ongoing issue of the lack of an official Canadian flag, sparking a serious debate about a flag change to replace the Union Flag. Out of three choices, the maple leaf design by George Stanley,[2] based on the flag of the Royal Military College of Canada, was selected. The flag made its first official appearance on February 15, 1965; the date is now celebrated annually as National Flag of Canada Day.

The Canadian Red Ensign had been unofficially used since the 1890s and was approved by a 1945 Order in Council for use "wherever place or occasion may make it desirable to fly a distinctive Canadian flag".[3][4] Also, the Royal Union Flag remains an official flag in Canada. There is no law dictating how the national flag is to be treated. There are, however, conventions and protocols to guide how it is to be displayed and its place in the order of precedence of flags, which gives it primacy over the aforementioned and most other flags.

Many different flags created for use by Canadian officials, government bodies, and military forces contain the maple leaf motif in some fashion, either by having the Canadian flag charged in the canton, or by including maple leaves in the design.

Origins and design

The flag is horizontally symmetric and therefore the obverse and reverse sides appear identical. The width of the Maple Leaf flag is twice the height. The white field is a Canadian pale (a square central band in a vertical triband flag, named after this flag); each bordering red field is exactly half its size[5] and it bears a stylized red maple leaf at its centre. In heraldic terminology, the flag's blazon as outlined on the original royal proclamation is "gules on a Canadian pale argent a maple leaf of the first".[6][7]

The maple leaf has been used as a Canadian emblem since the 18th century.[9] It was first used as a national symbol in 1868 when it appeared on the coat of arms of both Ontario and Quebec.[10] In 1867, Alexander Muir composed the patriotic song "The Maple Leaf Forever", which became an unofficial anthem in English-speaking Canada.[11] The maple leaf was later added to the Canadian coat of arms in 1921.[10] From 1876 until 1901, the leaf appeared on all Canadian coins and remained on the penny after 1901.[12] The use of the maple leaf by the Royal Canadian Regiment as a regimental symbol extended back to 1860.[13] During the First World War and Second World War, badges of the Canadian Forces were often based on a maple leaf design.[14] The maple leaf would eventually adorn the tombstones of Canadian military graves.[15]

By proclaiming the Royal Arms of Canada, King George V in 1921 made red and white the official colours of Canada; the former came from Saint George's Cross and the latter from the French royal emblem since King Charles VII.[16] These colours became "entrenched" as the national colours of Canada upon the proclamation of the Royal Standard of Canada (the Canadian monarch's personal flag) in 1962.[17] The Department of Canadian Heritage has listed the various colour shades for printing ink that should be used when reproducing the Canadian flag; these include:[5]

- FIP red: General Printing Ink, No. 0-712;

- Inmont Canada Ltd., No. 4T51577;

- Monarch Inks, No. 62539/0

- Rieger Inks, No. 25564

- Sinclair and Valentine, No. RL163929/0.

The number of points on the leaf has no special significance;[18] the number and arrangement of the points were chosen after wind tunnel tests showed the current design to be the least blurry of the various designs when tested under high wind conditions.[19] The image of the maple leaf used on the flag was designed by Jacques Saint-Cyr;[20] however, Jack Cook claims that this stylized eleven-point maple leaf was lifted from a copyrighted design owned by a Canadian craft shop in Ottawa.[21] The colours 0/100/100/0 in the CMYK process, PMS 032 (flag red 100%), or PMS 485 (used for screens) in the Pantone colour specifier can be used when reproducing the flag.[5] For the Federal Identity Program, the red tone of the standard flag has an RGB value of 255–0–0 (web hexadecimal #FF0000).[22] In 1984, the National Flag of Canada Manufacturing Standards Act was passed to unify the manufacturing standards for flags used in both indoor and outdoor conditions.[23]

History

Early flags

The first flag known to have flown in Canada was the St George's Cross carried by John Cabot when he reached Newfoundland in 1497. In 1534, Jacques Cartier planted a cross in Gaspé bearing the French royal coat of arms with the fleurs-de-lis. His ship flew a red flag with a white cross, the French naval flag at the time. New France continued to fly the evolving French military flags of that period.[4][24] As the de jure national flag of the United Kingdom, the Union Flag (commonly known as the Union Jack and, by law, called the Royal Union Flag in Canada since 1964) was used similarly in Canada since the 1621 British settlement in Nova Scotia. Its use continued after Canada's independence from the United Kingdom in 1931 until the adoption of the current flag in 1965.[4]

Shortly after Canadian Confederation in 1867, the need for distinctive Canadian flags emerged. The first Canadian flag was that then used as the flag of the Governor General of Canada, a Union Flag with a shield in the centre bearing the quartered arms of Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick surrounded by a wreath of maple leaves.[25] In 1870 the Red Ensign, with the addition of the Canadian composite shield in the fly, began to be used unofficially on land and sea[26] and was known as the Canadian Red Ensign. As new provinces joined the Confederation, their arms were added to the shield. In 1892, the British admiralty approved the use of the Red Ensign for Canadian use at sea.[26] The composite shield was replaced with the coat of arms of Canada upon its grant in 1921 and, in 1924, an Order in Council approved its use for Canadian government buildings abroad.[4] In 1925, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King established a committee to design a flag to be used at home, but it was dissolved before the final report could be delivered. Despite the failure of the committee to solve the issue, public sentiment in the 1920s was in favour of fixing the flag problem for Canada.[27] New designs were proposed in 1927,[28] 1931,[29] and 1939.[30]

During the Second World War, the Red Ensign was the recognized Canadian national flag. A joint committee of the Senate and House of Commons was appointed on November 8, 1945, to recommend a national flag to officially adopt. It received 2,409 designs from the public and was addressed by the director of the Historical Section of the Canadian Army, Fortescue Duguid, who pointed out red and white were Canada's official colours and there was already an emblem representing the country: three joined maple leaves seen on the escutcheon of the Canadian coat of arms.[26] By May 9 the following year, the committee reported back with a recommendation "that the national flag of Canada should be the Canadian red ensign with a maple leaf in autumn golden colours in a bordered background of white". The Legislative Assembly of Quebec, however, had urged the committee to not include any of what it deemed as "foreign symbols", including the Union Flag, and Mackenzie King, then still prime minister, declined to act on the report, leaving the order to fly the Canadian Red Ensign in place.[16][25][31]

Great Flag Debate

By the 1960s, debate for an official Canadian flag intensified and became a subject of controversy, culminating in the Great Flag Debate of 1964.[32] In 1963, the minority Liberal government of Lester B. Pearson gained power and decided to adopt an official Canadian flag through parliamentary debate. The principal political proponent of the change was Pearson. He had been a significant broker during the Suez Crisis of 1956, for which he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.[33] During the crisis, Pearson was disturbed when the Egyptian government objected to Canadian peacekeeping forces on the grounds that the Canadian flag (the Red Ensign) contained the same symbol (the Union Flag) also used as a flag by the United Kingdom, one of the belligerents.[33] Pearson's goal was for the Canadian flag to be distinctive and unmistakably Canadian. The main opponent to changing the flag was the leader of the opposition and former prime minister, John Diefenbaker, who eventually made the subject a personal crusade.[34]

In 1961, Leader of the Opposition Lester Pearson asked John Ross Matheson to begin researching what it would take for Canada to have a new flag. Pearson knew the Red Ensign with the Union Jack was unpopular in Quebec, a base of support for his Liberal Party, but the Red Ensign was strongly favoured by English Canada. By April 1963, Pearson was prime minister in a minority government and risked losing power over the issue. He formed a 15-member multi-party parliamentary committee in 1963 to select a new design, despite opposition leader Diefenbaker's demands for a referendum on the issue.[35] On May 27, 1964, Pearson's cabinet introduced a motion to parliament for adoption of his favourite design, presented to him by artist and heraldic advisor Alan Beddoe,[26] of a "sea to sea" (Canada's motto) flag with blue borders and three conjoined red maple leaves on a white field. This motion led to weeks of acrimonious debate in the House of Commons and the design came to be known as the "Pearson Pennant",[36] derided by the media and viewed as a "concession to Québec".[26]

Flag today

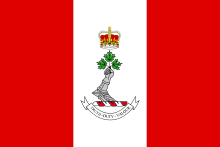

A new all-party committee was formed in September 1964, comprising seven Liberals, five Conservatives, one New Democrat, one Social Crediter, and one Créditiste, with Herman Batten as chairman, while John Matheson acted as Pearson's right-hand man.[26] Among those who gave their opinions to the group were Duguid, expressing the same views as he had in 1945, insisting on a design using three maple leaves; Arthur R. M. Lower, stressing the need for a distinctly Canadian emblem; Marcel Trudel, arguing for symbols of Canada's founding nations, which did not include the maple leaf (a thought shared by Diefenbaker); and A. Y. Jackson, providing his own suggested designs.[26] Also considered by a steering committee were approximately 2,000 suggestions from the public, in addition to 3,900 others, "including those that had accumulated in the Department of the Secretary of State and those from a parliamentary flag committee of 1945–1946".[26] Through a six-week period of study with political manoeuvring, the committee took a vote on the two finalists: the Pearson Pennant (Beddoe's design) and the current design. Believing the Liberal members would vote for the Prime Minister's preference, the Conservatives voted for the single leaf design. The Liberals, though, all voted for the same, giving a unanimous, 14 to 0 vote[26] for the option created by George Stanley and inspired by the flag of the Royal Military College of Canada (RMC) in Kingston, Ontario.[37]

There, near the parade square, in March 1964, while viewing the college flag atop the Mackenzie Building, Stanley, then RMC's Dean of Arts, first suggested to Matheson, then Member of Parliament for Leeds, that the RMC flag should form the basis of the national flag. The suggestion was followed by Stanley's memorandum of March 23, 1964, on the history of Canada's emblems,[38] in which he warned that any new flag "must avoid the use of national or racial symbols that are of a divisive nature" and that it would be "clearly inadvisable" to create a flag that carried either the Union Jack or a fleur-de-lis. According to Matheson, Pearson's one "paramount and desperate objective" in introducing the new flag was to keep Quebec in the Canadian union.[39] It was Dr. Stanley's idea that the new flag should be red and white and that it should feature the single maple leaf; his memorandum included the first sketch of what would become the flag of Canada. Stanley and Matheson collaborated on a design that was ultimately, after six months of debate and 308 speeches,[26] passed by a majority vote in the House of Commons on December 15, 1964. Just after this, at 2:00 am, Matheson wrote to Stanley: "Your proposed flag has just now been approved by the Commons 163 to 78. Congratulations. I believe it is an excellent flag that will serve Canada well."[40] The Senate added its approval two days later.[16]

Elizabeth II, Queen of Canada, proclaimed the new flag on January 28, 1965,[16] and it was inaugurated on February 15 of the same year at an official ceremony held on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, in the presence of Governor General Major-General Georges Vanier, the Prime Minister, other members of the Cabinet, and Canadian parliamentarians. The Red Ensign was lowered at the stroke of noon and the new maple leaf flag was raised. The crowd sang "O Canada" followed by "God Save the Queen".[41] Of the flag, Vanier said "[it] will symbolize to each of us—and to the world—the unity of purpose and high resolve to which destiny beckons us."[42] Maurice Bourget, Speaker of the Senate, said: "The flag is the symbol of the nation's unity, for it, beyond any doubt, represents all the citizens of Canada without distinction of race, language, belief, or opinion."[41] Yet there was still opposition to the change, and Stanley's life was even threatened for having "assassinated the flag". In spite of this, Stanley attended the flag raising ceremony.[43]

At the time of the 50th anniversary of the flag, the government—held by the Conservative Party—was criticized for the lack of official ceremony dedicated to the date; accusations of partisanship were levelled.[42] Minister of Canadian Heritage Shelly Glover denied the charges and others, including Liberal Members of Parliament, pointed to community events taking place around the country.[42] Governor General David Johnston did, though, preside at an official ceremony at Confederation Park in Ottawa, integrated with Winterlude. He said "[t]he National Flag of Canada is so embedded in our national life and so emblematic of our national purpose that we simply cannot imagine our country without it."[44] Queen Elizabeth II stated: "On this, the 50th anniversary of the National Flag of Canada, I am pleased to join with all Canadians in the celebration of this unique and cherished symbol of our country and identity."[45] A commemorative stamp and coin were issued by Canada Post and the Royal Canadian Mint, respectively.[44]

Flags used in Canada from 1497 to the present

Flag on John Cabot's ship, and used during the English colonization of the Americas before the Act of Union (1497-1707)

Flag on John Cabot's ship, and used during the English colonization of the Americas before the Act of Union (1497-1707) Flag used during the Scottish colonization of the Americas before the Act of Union (1621-1707)

Flag used during the Scottish colonization of the Americas before the Act of Union (1621-1707) Flag of France at time of Jacques Cartier (1534–1604)

Flag of France at time of Jacques Cartier (1534–1604).svg.png) Merchant Flag used by Champlain and French merchants (1604–1663)

Merchant Flag used by Champlain and French merchants (1604–1663) New France Flag (1663–1763)

New France Flag (1663–1763)

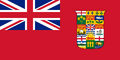

Flag used (1868–1921)

Flag used (1868–1921) 1907 Canadian Red Ensign commonly used in Western Canada. Note the inclusion of all the provincial crests.

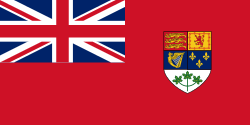

1907 Canadian Red Ensign commonly used in Western Canada. Note the inclusion of all the provincial crests. Flag used (1921–1957)

Flag used (1921–1957).svg.png) 1957 version of the Canadian Red Ensign that had evolved as the de facto national flag until 1965

1957 version of the Canadian Red Ensign that had evolved as the de facto national flag until 1965 First Flag Proposal to Parliament, the Pearson Pennant

First Flag Proposal to Parliament, the Pearson Pennant Flag of the Royal Military College of Canada; used as inspiration by George F.G. Stanley

Flag of the Royal Military College of Canada; used as inspiration by George F.G. Stanley.svg.png) Earlier (1964) version of the proposal that was adopted

Earlier (1964) version of the proposal that was adopted Current flag, (1965–present)

Current flag, (1965–present).svg.png) Current flag, using Pantone specifications.

Current flag, using Pantone specifications.

Proclamation

After the resolutions proposing a new national flag for Canada were passed by the two houses of parliament, a proclamation was drawn up for signature by the Canadian queen. This was created in the form of an illuminated document on vellum, with calligraphy by Yvonne Diceman and heraldic illustrations. The text was rendered in black ink, using a quill, while the heraldic elements were painted in gouache with gilt highlights. The Great Seal of Canada was applied in wax over a silk ribbon.[46]

.jpg)

This parchment was signed discreetly by the calligrapher, but was made official by the signatures of Queen Elizabeth II, Prime Minister Lester Pearson, and Attorney General Guy Favreau. In order to obtain these signatures, the document was flown to the United Kingdom (for the Queen's royal sign-manual) and to the Caribbean (for the signature of Favreau, who was on vacation). This transport to different climates, combined with the quality of the materials with which the proclamation was created, and the subsequent storage and repair methods (including the use of Scotch Tape) contributed to the deterioration of the document: The gouache was flaking off, leaving gaps in the heraldic designs, most conspicuously on the red maple leaf of the flag design in the centre of the sheet, and the adhesive from the tape had left stains. A desire to have the proclamation as part of a display at the Canadian Museum of Civilization marking the flag's 25th anniversary led to its restoration in 1989. The proclamation is today stored in a temperature and humidity controlled, plexiglass case, so as to prevent the velum from changing dimensionally.[46]

Alternative flags

As a symbol of the nation's membership in the Commonwealth of Nations, the Royal Union Flag is an official Canadian flag and is flown on certain occasions.[47] Regulations require federal installations to fly the Royal Union Flag beside the national flag when physically possible, using a second flagpole, on the following days: Commonwealth Day (the second Monday in March), Victoria Day (the same date as the Canadian sovereign's official birthday), and the anniversary of the Statute of Westminster (December 11). The Royal Union Flag can also be flown at the National War Memorial or at other locations during ceremonies that honour Canadian involvement with forces of other Commonwealth nations during times of war. The national flag always precedes the Royal Union Flag, with the former occupying the place of honour.[47] The Royal Union Flag is also part of the provincial flags of Ontario and Manitoba, forming the canton of these flags; a stylized version is used on the flag of British Columbia and the flag of Newfoundland and Labrador.[47] Several of the provincial lieutenant governors formerly used a modified union flag as their personal standard, but the Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia is the only one who retains this design.[47] The Royal Union Flag and Red Ensign are still flown in Canada by veterans' groups and others who continue to stress the importance of Canada's British heritage and the Commonwealth connection.[47]

The Red Ensign is occasionally still used as well, including official use at some ceremonies. It was flown at the commemorations of the Battle of Vimy Ridge in 2007.[48][49] This decision elicited criticism from those who believe it should not be given equal status to the Canadian flag and received praise from people who believe that it is important to retain the ties to Canada's past.[48][49]

In Quebec, the provincial flag (a white cross on a field of blue with four fleurs-de-lis) can be considered a national flag along with the Maple Leaf flag, as is the Acadian flag in the Acadian regions of the Maritime provinces,[20][50] and the flags of the Iroquois Nation, the Metis Nation and other groups.

Protocol

No law dictates the proper use of the Canadian flag. However, Canadian Heritage has released guidelines on how to correctly display the flag alone and with other flags. The guidelines deal with the order of precedence in which the Canadian flag is placed, where the flag can be used, how it is used, and what people should do to honour the flag. The suggestions, titled Flag Etiquette in Canada, were published by Canadian Heritage in book and online formats and last updated in August 2011.[51] The flag itself can be displayed on any day at buildings operated by the Government of Canada, airports, military bases, and diplomatic offices, as well as by citizens, during any time of the day. When flying the flag, it must be flown using its own pole and must not be inferior to other flags, save for, in descending order, the Queen's standard, the governor general's standard, any of the personal standards of members of the Canadian Royal Family, or flags of the lieutenant governors.[52] The Canadian flag is flown at half-mast in Canada to indicate a period of mourning. Canadian Forces does have a special protocol for folding the Canadian flag for presentations, such as during a funeral ceremony; however, CF does not recommend this method for everyday use.[53]

Promoting the flag

Since the adoption of the Canadian flag in 1965, the Canadian government has sponsored programs to promote it. Examples include the Canadian Parliamentary Flag Program of the Department of Canadian Heritage and the flag program run by the Department of Public Works. These programs increased the exposure of the flag and the concept that it was part of the national identity. To increase awareness of the new flag, the Parliamentary Flag Program was set up in December, 1972, by the Cabinet and, beginning in 1973,[54] allowed members of the House of Commons to distribute flags and lapel pins in the shape of the Canadian flag to their constituents. Flags that have been flown on the Peace Tower and the East and West Blocks of Parliament Hill are packaged by the Department of Public Works and offered to the public free of charge. However, the program has a 34-year waiting list for East and West Block flags, and a 48-year waiting list for Peace Tower flags.[55]

Since 1996, February 15 has been commemorated as National Flag of Canada Day.[41] In 1996, Minister of Canadian Heritage Sheila Copps instituted the One in a Million National Flag Challenge.[56] This program was intended to provide Canadians with a million new national flags in time for Flag Day, 1997. The program was controversial because it cost some $45 million, and provided no means to hoist or fly the flags. The official numbers from Canadian Heritage put the expenses at $15.5 million, with approximately a seventh of the cost offset by donations.[57]

See also

- National Flag of Canada Day

- National symbols of Canada

- List of Canadian provincial and territorial symbols

References

- ↑ (Matheson 1980), p. 177

- ↑ Richard Foot (13 February 2014). "The Stanley Flag". The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Stacey, C. P., ed. (1972). "19. Order in Council on the Red Ensign, 1945". Historical documents of Canada. 5. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 28. ISBN 0-7705-0861-8.

- 1 2 3 4 "First "Canadian flags"". Department of Canadian Heritage. September 24, 2007. Retrieved December 16, 2008.

- 1 2 3 Department of Canadian Heritage (January 1, 2003). "The National Flag of Canada: Colours Specification". Queen's Printer for Canada. Archived from the original on December 20, 2008. Retrieved December 20, 2008.

- ↑ Department of Canadian Heritage. "Description of the Proclamation by Her Majesty Elizabeth the Second which formalized the National Flag of Canada in 1965". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ↑ The flag was later registered with the Canadian Heraldic Authority on March 15, 2005 as "Gules on a Canadian pale Argent a maple leaf Gules".[8]

- ↑ "Registration of the National Flag of Canada". The Public Register of Arms, Flags and Badges of Canada. Queen's Printer for Canada. March 15, 2005. Retrieved May 18, 2010.

- ↑ James Minahan (2009). The Complete Guide to National Symbols and Emblems: Volume 2. Greenwood Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-313-34500-5.

- 1 2 Jeanette Hanna; Alan C. Middleton (2008). Ikonica: A Field Guide to Canada's Brandscape. Douglas & McIntyre. pp. 79–. ISBN 978-1-55365-275-5.

- ↑ Caren Irr (1998). The Suburb of Dissent: Cultural Politics in the United States and Canada During the 1930s. Duke University Press. p. 69. ISBN 0-8223-2192-0.

- ↑ W. K. Cross (2011). Canadian Coins: Collector and Maple Leaf Issues. Charlton Press. p. intro. ISBN 978-0-88968-342-6.

- ↑ Tim Herd (2012). Maple Sugar: From Sap to Syrup: The History, Lore, and How-To Behind This Sweet Treat. Storey Publishing, LLC. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-61212-211-3.

- ↑ J. L. Granatstein (2011). Canada's Army: Waging War and Keeping the Peace. University of Toronto Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-4426-1178-8.

- ↑ "Understanding the Cemeteries and Monuments" (PDF). Canadian Military History (Wilfrid Laurier University). 2005.

- 1 2 3 4 Department of Canadian Heritage. "Birth of the Canadian flag". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved December 16, 2008.

- ↑ Tidridge, Nathan (2011). Thompson, Allister, ed. Canada's Constitutional Monarchy. Toronto: Dundurn Press. p. 222. ISBN 9781554889808.

- ↑ Department of Canadian Heritage. "You were asking...". Queen's Printer for Canada. Archived from the original on April 30, 2010. Retrieved April 13, 2008.

- ↑ (Matheson 1980)

- 1 2 Archbold 2002

- ↑ "The Eleven Point Maple Leaf". Canada's Four Corners. Retrieved March 9, 2012.

- ↑ "Government of Canada FIP Signature". Industry Canada. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ↑ "National Flag of Canada Manufacturing Standards Act". Justice Laws Website. laws-lois.justice.gc.ca. Retrieved December 3, 2016.

- ↑ "National Flag and Emblems". Portrait of Québec. Government of Quebec. October 12, 2006. Retrieved April 20, 2008.

- 1 2 Fraser, Alistair B. (January 30, 1998). "A Canadian Flag for Canada". The Flags of Canada. Retrieved April 20, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "National Flag of Canada", The Canadian Encyclopedia, Historica Canada, retrieved 13 February 2015

- ↑ Archbold 2002, p. 61

- ↑ Office of the Governor General of Canada: Canadian Heraldic Authority (March 20, 2008). "Proposed Flag for Canada: Anatole Vanier, 1927". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved November 22, 2012.

- ↑ Office of the Governor General of Canada: Canadian Heraldic Authority (March 20, 2008). "Proposed Flag for Canada: Gérard Gallienne, 1931". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved November 22, 2012.

- ↑ Office of the Governor General of Canada: Canadian Heraldic Authority (March 20, 2008). "Proposed Flag for Canada: Ephrem Côté". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved November 22, 2012.

- ↑ "The Flag Debate". Mount Allison University. Archived from the original on April 24, 2008. Retrieved April 17, 2008.

- ↑ "The Great Flag Debate". CBC. Retrieved April 13, 2008.

- 1 2 Thorner 2003, p. 524

- ↑ "The Great Canadian Flag Debate". CBC. Retrieved March 31, 2008.

- ↑ Corbett, Ron (June 30, 2013). "Flag designer recalls how he came up with the Maple Leaf design". Toronto Sun. Retrieved October 4, 2013.

- ↑ Reeve, Iain (May 21, 2007). "Wrong turns on the road of symbolism". The Peak. Retrieved April 13, 2008.

- ↑ "Canadian Heritage Flags". Canadianheritage.gc.ca. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ↑ "George F.G. Stanley's Flag Memorandum to John Matheson, 23 March 1964 (includes Dr. Stanley's original sketches for the Canadian Flag)".

- ↑ Mackey, Eva. 2002. The House of Difference. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. page 56

- ↑ John Matheson's postcard to George Stanley, 15 December 1964, 2:00 AM, announcing the House of Commons' approval of Stanley's design for the new Canadian Flag

- 1 2 3 "The National Flag of Canada; A symbol of Canadian Identity". Department of Canadian Heritage. Retrieved February 15, 2007.

- 1 2 3 Milewiski, Terry (February 15, 2015). "Canada's flag debate flaps on, 50 years later". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ↑ The real story behind the Canadian Flag (CBC News report, 2015)

- 1 2 Office of the Governor General of Canada (February 15, 2015). "Governor General to Celebrate the 50th Anniversary of the National Flag of Canada". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ↑ Office of the Governor General of Canada (February 15, 2015). "Message from Her Majesty The Queen on the Occasion of the 50th Anniversary of the National Flag of Canada". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- 1 2 Grace, John (1990). Library and Archives Canada, ed. "Conserving the Proclamation of the Canadian Flag". The Archivist. National Archives of Canada. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Department of Canadian Heritage (January 1, 2003). "The Royal Union Flag". Queen's Printer for Canada. Archived from the original on May 6, 2006. Retrieved May 20, 2006.

- 1 2 "Globe Editorial: Red Ensign". The Globe and Mail. March 31, 2007. Archived from the original on January 9, 2008. Retrieved March 2, 2014.

- 1 2 Peritz, Ingrid (July 9, 2007). "Dallaire slams decision to fly Red Ensign". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved April 13, 2008.

- ↑ "Flag and emblems of Québec, An Act respecting the, R.S.Q. D-12.1". CanLil. September 1, 2004. Retrieved March 25, 2008.

- ↑ "Rules for Flying the Flag". Department of Canadian Heritage. August 5, 2011. Retrieved July 27, 2012.

- ↑ "The Honours, Flags and Heritage Structure of the Canadian Forces" (PDF). Department of National Defence (Canada). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 25, 2009. Retrieved March 25, 2008.

- ↑ "Process for the Ceremonial Folding of the National Flag of Canada". Directorate of History and Heritage – National Defence Canada. April 23, 2008. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

- ↑ "Administration of the Parliamentary Flag Program". Department of Canadian Heritage. January 1, 2003. Retrieved May 20, 2006.

- ↑ "Canadian Flag". Government of Canada. Retrieved October 22, 2014.

- ↑ Dee, Duncan (February 19, 1996). "Heritage Minister Sheila Copps Launches "One In A Million National Flag" Campaign". Department of Canadian Heritage. Retrieved March 25, 2008.

- ↑ Arnsby, Julia (February 15, 1997). "Canadians Meet the "One in a Million National Flag" Challenge". Department of Canadian Heritage. Retrieved March 25, 2008.

Bibliography

- Archbold, Rick (2002). I Stand For Canada. Macfarlane Walter & Ross. ISBN 1-55199-108-X.

- Levine, Allan. "The Great Flag Debate" Canada’s History 94#6 (2014–15): 32–37

- Matheson, Col. John R. (1980). Canada's Flag: a search for a country. Mika Publishing Company. ISBN 0-919303-01-3.

- Stanley, Dr. George F.G. (1965). The Story of Canada's Flag: A Historical Sketch. Ryerson Press.

- Thompson, Hugh (2002). Canada. Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 0-7894-9561-9.

- Thorner, Thomas (2003). A Country Nourished on Self-Doubt: Documents in Post-Confederation Canadian History. Broadview Press. ISBN 1-55111-548-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Flags of Canada / Drapeaux du Canada. |

- National Flag of Canada – Department of Canadian Heritage

- National Flag of Canada etiquette – Department of Canadian Heritage

- Flags (Heritage Minutes) – Historica Canada

- George F.G. Stanley's Flag Memorandum to John Matheson – St. Francis Xavier University

- John Matheson's postcard to George Stanley – St. Francis Xavier University

- Royal Proclamation – Library and Archives Canada

- Canada at Flags of the World

- The Great Canadian Flag Debate – CBC Digital Archives

- "The People's Choice: Seeking the origins of the Maple Leaf flag, finding the soul of our nation" – W5 (CTV)

- "The Maple Leaf Forever?" – The Agenda (TVO)