California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

| California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation | |

|---|---|

| Common name | Department of Corrections |

| Abbreviation | CDCR |

|

Patch of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation | |

|

Logo of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation | |

|

Badge Patch of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation | |

| Agency overview | |

| Formed | 1885 |

| Preceding agency |

California Department of Corrections, California Youth Authority |

| Employees | 66,800 |

| Annual budget | US$10.1 billion (2011) |

| Legal personality | Governmental: Government agency |

| Jurisdictional structure | |

| Operations jurisdiction* | State of California, USA |

| Size | 163,696 square miles (423,970 km2) |

| Population | 36,756,666 (2008 est.)[1] |

| Legal jurisdiction | As per operations jurisdiction. |

| General nature | |

| Operational structure | |

| Headquarters | Sacramento, California |

| Agency executive | Scott Kernan, Secretary |

| Website | |

|

www | |

| Footnotes | |

| * Divisional agency: Division of the country, over which the agency has usual operational jurisdiction. | |

The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) is responsible for the operation of the California state prison and parole systems. Its headquarters are in Sacramento.

Staff size

CDCR is the 3rd largest law enforcement or (police agency) in the United States behind the New York City Police Department, Customs and Border Protection (CBP) which employs approximately 60,000 officers and 40,000 police officers respectively. CDCR correctional officers are sworn law enforcement officers (CA state peace officers) with peace officer powers.

As of 2013, CDCR employed approximately 24,000 peace officers (state correctional officers), 1,500 state parole agents, and 700 criminal investigators/special agents.

History

In 1851, California activated its first state run institutions. This institution was a 268-ton wooden ship named The Waban, and was anchored in the San Francisco Bay.[2] The prison ship housed 30 inmates who subsequently constructed San Quentin State Prison, which opened in 1852 with approximately 68 inmates.[3]

Since 1852, the Department has activated thirty one prisons across the state. CDCR's history dates back to 1912 when the agency was called California State Detentions Bureau. In 1951 it was renamed California Department of Corrections. In 2004 it was renamed California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR).

Reorganization (2000s)

In 2004, a Corrections Independent Review Panel appointed by Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and led by former Governor George Deukmejian noted "California's $6 billion correctional system suffers from a multitude of problems—out-of-control costs; a recidivism rate far exceeding that of any other state; reported abuse of inmates by correctional officers; an employee disciplinary system that fails to punish wrongdoers; and the failure of correctional institutions to provide youth wards and inmates with mandated health care and other services."[4]

Among other recommendations to address these problems, the Panel suggested "Reorganizing the Youth and Adult Correctional Agency".[4] The Agency had consisted of "the Department of Corrections, the Department of the Youth Authority, the Board of Prison Terms, the Board of Corrections, the Commission on Correctional Peace Officer Standards and Training, the Narcotic Addict Evaluation Board and the Youth Authority Board."[5]

Schwarzenegger made a reorganization plan public in January 2005 implementing many of the recommendations of the panel but without "a citizens commission overseeing the state's entire correctional operation."[6] The reorganization became effective on July 1, 2005.[5] The CDCR superseded the:[7]

- Youth and Adult Correctional Agency

- Department of Corrections

- Department of the Youth Authority

- Commission on Correctional Peace Officer Standards and Training

- Board of Corrections

- State Commission on Juvenile Justice, Crime and Delinquency Prevention

The CDCR's current Divisions and Boards include (among others):[8][9]

- Division of Juvenile Justice, formerly known as the California Youth Authority (Department of the Youth Authority). This has a 2006/07 budget of $530 million and 3,776 employees, of which 1,970 are custody staff.[10]

- Division of Adult Institutions, responsible for the adult prisons, and Division of Adult Parole Operations. These have a 2006/07 budget of $8.75 billion and 57,641 employees, of which 32,772 are sworn peace officers.[11]

- Board of Parole Hearings, which combines the old Board of Prison Terms, the Narcotic Addict Evaluation Authority, and the Youth Authority Board.

- Corrections Standards Authority, whose functions parallel those of the former Board of Corrections and the former Commission on Correctional Peace Officer Standards and Training.

Organization

Headquarters

Newsletter http://www.insidecdcr.ca.gov/

Divisions and boards

- Adult Operations

- Adult Parole

- Adult Programs

- Board of Parole Hearings

- Council on Mentally Ill Offenders (COMIO)

- Corrections Standards Authority

- Juvenile Justice

- CPHCS Contract Branch

- Prison Industry Authority (CALPIA)

- State Commission on Juvenile Justice

Facilities

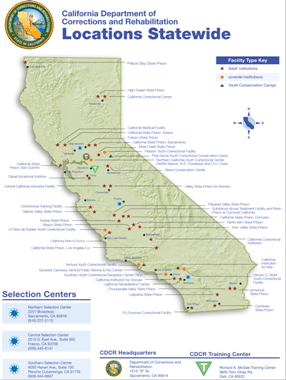

CDCR operates all state institutions, and oversees variety of community correctional facilities and camps, monitors all parolees during their entry back into society.

Institutions

According to the Department's official Web site, "Currently there are 33 adult correctional institutions, 13 adult community correctional facilities, and eight juvenile facilities in California that house more than 165,000 adult offenders and nearly 3,200 juvenile offenders."[12] This inmate population makes the CDCR the largest state-run prison system in the United States.[13]

Regarding adult prisons, CDCR has the task of receiving and housing inmates that were convicted of felony crimes within the State of California. When an adult inmate arrives at a state prison, he/she is assigned a classification based on his/her committed offense. Each prison is designed to house different varieties of inmate offenders, from Level I inmates to Level IV inmates; the higher the level, the higher risk the inmate poses. Selected prisons within the state are equipped with security housing units, reception centers, and/or "condemned" units. These security levels are defined as follows:[14]

- Level I: "Open dormitories without a secure perimeter."

- Level II: "Open dormitories with secure perimeter fences and armed coverage."

- Level III: "Individual cells, fenced perimeters and armed coverage."

- Level IV: "Cells, fenced or walled perimeters, electronic security, more staff and armed officers both inside and outside the installation."

- Security Housing Unit (SHU): "The most secure area within a Level IV prison designed to provide maximum coverage." These are designed to handle inmates that cannot be housed with the general population of inmates. This includes inmates that are validated prison gang members, gang bosses or shot callers, etc.

- Reception Center (RC): "Provides short term housing to process, classify and evaluate incoming inmates."

- Condemned (Cond): "Holds inmates with death sentences."

Parole

According to the Department's official Web site, "there are more than 148,000 adult parolees and 3,800 juvenile parolees supervised by the CDCR."[12] A 2002 article found that "California's growth in the numbers of people on parole supervision—and in the numbers whose parole has been revoked—has far exceeded the growth in the rest of the nation."[15] California accounted for 12 percent of the U.S. population but 18% of the U.S. parole population, and almost 90,000 California parolees returned to prison in 2000.[15]

At San Quentin, the non-profit organization California Reentry Program "helps inmates re-enter society after they serve their sentences."[16]

CDCR peace officers

CDCR correctional law enforcement officers are peace officers as indicated in California penal code sections 830.2 and 830.5, as their primary duties are to provide public safety, corrections, and law enforcement services in and outside of state institutional grounds, state operated medical facilities, and camps while engaged in the performance of their duties.

The primary duties of these officers include, but are not limited to, providing public safety and law enforcement services in and around California's adult and youth institutions, fire camps, and state operated medical facilities and hospitals, and community correctional facilities. These officers also monitor and supervise parolees who are released back into the general public. Other primary duties include investigation and apprehension of institutional escapees and parolees at large (PAL), prison gangs, statewide narcotics enforcement and investigations (involving institutions), etc.

Special Service Unit

In addition to correctional officers, CDCR employs approximately 30 special agents (criminal investigators) who are assigned to offices throughout the state. These agents conduct criminal investigations involving parolees and inmates, monitor prison gangs, gather intelligence and conduct narcotics enforcement. These investigators are part of an elite unit known as the Special Service Unit or simply SSU. Special agents work closely with other law enforcement agencies, such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation, California Department of Justice and local police and sheriff departments. SSU special agents hold the state equivalency of a CDCR captain. As a confidential employee, they are able to keep a low profile and small footprint while carrying out very high-profile cases.

History

The Special Service Unit of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) was formed in 1963, at the request of then California Governor Edmund Brown. Sadly, the formation of the unit is said to have evolved after the March 9, 1963 kidnapping of two Los Angeles police officers. The kidnapping and subsequent murder of one of the officers was committed by two state parolees, Gregory Powell and Jimmy Lee Smith (a.k.a., Jimmy Youngblood). LAPD officers Ian Campbell and Karl Hettinger conducted a routine traffic stop on Powell and Smith in the Hollywood area. As the two officers approached the car, they were kidnapped at gunpoint by the two parolees and forced into Powell's car. They were driven north from Los Angeles to an onion field near Bakersfield, where Officer Campbell was fatally shot. Officer Hettinger was able to escape.

In the police investigation that ensured after the incident, the ability for LAPD detectives to get timely and necessary information from the Department of Corrections was severely hampered, ostensibly by the size and bureaucracy of the department. Detectives needed a way to obtain information quickly and have the assistance of the CDCR resources. Because of this tragic incident and the legislative conferences afterward, a decision was made to form the Special Service Unit.

Charles Casey, who was an assistant director with CDCR at the time, learned of a unit within the New York Department of Corrections that seemed to bridge the gap between New York state parole services and local law enforcement. Casey met with Russell H. Oswald, chairman of the New York State Parole Board, who was the founder of the Bureau of Special Services within the New York parole division. Based upon his study and evaluation of the Bureau of Special Services, Casey came back to California and designed a similar unit, calling it the Special Service Unit. After the legislature approved the formation, the unit officially began services in 1964.

The unit serves as the primary investigative unit for CDCR on cases that stem from the prison or state parolees and affect the street. According to its official description, SSU "conducts the major criminal investigations and prosecutions, criminal apprehension efforts of prison escapees and parolees wanted for serious and violent felonies, is the primary departmental gang management unit, conducts complex gang related investigations of inmates and parolees suspected of criminal gang activity; and is the administrative investigative and law enforcement liaison unit." In layman's terms, this means the unit does anything asked of it to keep communities safe.

High profile cases

Throughout its fifty-year history the Special Service Unit has been quietly involved in numerous high profile cases. One such example is the Patricia Hearst kidnapping by the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA) in 1974. The SLA was a radical left-wing organization formed in Soledad Prison by Donald DeFreeze. In 1973 Defreeze escaped from prison and was leading the SLA on the streets when they kidnapped Hearst. The day after Hearst's kidnapping, special agents from the unit's San Francisco office provided police with photographs of suspects who matched the overall description of one of the abductors. Thanks to photographs supplied by SSU, DeFreeze was positively identified as one of Hearst's abductors. That identification led to a lengthy investigation of SLA and its origination behind prison walls.

Another example is the high profile murders that shook Los Angeles in the late sixties. The murders were committed by members of Charles Manson's cult and came to be known as Helter Skelter. During the course of the investigation into the cult, SSU special agents were requested by Los Angeles Police to interview Bruce Davis, a Manson follower who had been convicted of the 1969 Gary Hinman murder in Los Angeles. Davis was Manson devotee whom police were trying to turn as an informant into many of the open murders linked to the Manson Family. On January 26, 2001, San Francisco resident Diane Whipple was attacked and killed by two large Presa Canario dogs in the hallway of her apartment building. The dogs, named Bane and Hera, were owned by Whipple's neighbors, Marjorie Knoller and Robert Noel. The dogs' actual owner, Paul Schneider, was a high-ranking member of the Aryan Brotherhood prison gang who was serving a life sentence in Pelican Bay State Prison. The Special Service Unit had been investigating the Aryan Brotherhood and its illegal dog breeding business for several months prior to the death of Whipple. SSU was able to assist local law enforcement during the investigation and prosecution of Knoller and Noel.

In August 2009, Phillip Garrido was arrested in Antioch, Calif., for the kidnapping of Jaycee Dugard. He had kidnapped her eighteen years prior and kept her in captivity. The Hayward (Calif.) police department had interest in Garrido as it related to the 1988 kidnapping of nine-year-old Michaela Garecht. Special agents from SSU assisted the detectives from the Hayward Police Department in the ensuing investigation. In 2011, they assisted in conducting interviews with Garrido and his wife, Nancy Garrido, who had both been sentenced to state prison in California. In August 2014, convicted murderer Scott Landers escaped from the back of a CDCR transport van while on the Interstate 5 freeway just north of Atwater, Calif. Landers had been convicted of the stabbing of a 61-year-old man in Riverside, Calif. and was serving twenty-five years to life. Upon his escape, members of the elite Special Service Unit were called in from across the state to lead the investigation. Within twenty-four hours, the escaped murderer was caught and brought back to CDCR custody.

Current structure

The current configuration of the Special Service Unit remains true to its origins- small and mobile. Although the number remains secretive, it has been said there are very few of these elite law officers. Estimates remain between 30-35 special agents who are actually assigned to this unit. They are based throughout California in clandestine, off-site locations. Every agent is equipped with tactical and surveillance equipment and is ready to respond anywhere within the state at a moment's notice.

In 2005, CDCR began to consolidate various divisions and units in an effort to realign its organizational structure. During that time the Office of Correctional Safety (OCS) was created, which serves as a special operations division for the department. Within the OCS are groups such as the Fugitive Apprehension Team (FAT) and the Emergency Operations Unit (EOU), CDCR's full-time SWAT team. SSU became a branch of OCS as well, which elevated the training and tactical acumen for all of the special agents. With the merge of the EOU unit with SSU, special agents were responsible for attaining a higher level of tactical firearms proficiency as well as tactical high risk entry training.

Serving as the "detective unit" for the Department of Corrections, SSU special agents are responsible for keeping current on the latest investigative techniques and current case law. Special agents often work hand-in-hand with law enforcement investigators from all branches of government, city, county and federal. Many SSU agents are assigned to regional task forces throughout California and a handful are cross-designated as federal task force officers with such federal partners as the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the Bureau of Alcohol Tobacco and Firearms (BATF).

Fugitive Apprehension Team

Another elite and low-profile unit, and purposely so, is the Fugitive Apprehension Team or FAT which is made up of just over 80 agents who are also assigned to offices throughout the state; many in the same complexes as SSU agents. FAT agents are also criminal investigators and are teamed with the Warrants Unit of the United States Marshals Service (USMS) in locating and apprehending individuals wanted for high violence offenses; whether under the jurisdiction of CDCR or local agencies. FAT agents provide services to local agencies whose resources do not allow them to pursue violent offenders who have fled their jurisdictions, to parole violators wanted for violent offenses, individuals wanted under Federal Warrants and they assist SSU agents in locating escapees from CDCR. FAT agents' powers extend to beyond the State of California as they are also sworn Special Deputies of the USMS. FAT agents are highly trained in high-risk warrant service execution and must complete a special academy to become members of the "Teams". Members of these teams are kept low profile for security reasons as their nature is to conduct investigations in locating violent fugitives and executing their apprehension in a timely basis.

FAT shares a sentimental affiliation with the historic California State Rangers, who were created in May 1853 by a California Legislative Act and organized by Captain Harry Love, to apprehend dangerous offenders of the time. In August 1853, after having fulfilled their purpose, the Rangers were mustered out of service. The affiliation that FAT shares, although remotely, is that in July 1996 the California State Legislature enacted specific funds earmarked via the Department of Corrections to create fugitive teams to locate and bring to justice parole violators, the most violent offenders of modern times.

CDCR also operates specialized units such as Investigations Services Unit (ISU), Institutional Gang Investigations (IGI), Transportation Unit, Crisis Response Teams or Special Emergency Response Team (CDCR's version of police SWAT team), Negotiations Management Unit (NMT), K-9 unit, and Narcotics Investigations.

As of May 2010, CDCR employed over 28,000 peace officers, classified by titles such as state correctional officers, sergeants, lieutenants, captains, counselors, parole agents, inspectors general, special agents (criminal investigators) and EMPs.

Correctional Peace Officer Academy

CDCR Peace Officers are trained to become Sworn Peace Officers of the State of California at the Basic Correctional Peace Officer Academy located in Galt, California. Cadets must complete a 12-week formal and comprehensive training program. The curriculum consists of 640 hours (four months) of training. Instruction includes but is not limited to firearms, chemical agents, non-lethal impact weapons, arrest and control techniques, state law and department policies and procedures.

Cadets must also successfully complete Peace Officer Standards and Training (POST) minimum requirement course. Upon completion of the academy cadets are sworn in as CDCR peace officers. Upon assignment to their work institution or location, these officers also undergo further training for two years as vocational apprentices (one year of which is spent on probation). Upon completion of their two-year training they are then considered regular state correctional peace officers (CDCR officers)[17]

Officers killed while on duty

According to the Officer Down Memorial Page Web site, since the inception of what is currently CDCR, 33 employees have been killed in the line of duty.[18] Of these 20 have been killed by inmates. Seventeen were custody employees, and three were non-custody employees who supervised inmates working in industrial areas. Fifteen deaths were from stab wounds, two were from gunshot wounds, two were from bludgeoning, and one was from being thrown from a tier.[19]

Death row

Condemned male prisoners are held at San Quentin State Prison. Condemned female prisoners are held at the Central California Women's Facility. Executions take place at San Quentin. The State of California took full control of capital punishment in 1891. Originally executions took place at San Quentin and at Folsom State Prison. Folsom's last execution occurred on December 3, 1937.[20] In previous eras the California Institution for Women housed the death row for women.[21]

Issues

Prison health care

There are at multiple ongoing lawsuits over medical care in the California prison system. Plata v. Brown is a federal class action civil rights lawsuit alleging unconstitutionally inadequate medical services, and as a result of a stipulation between the plaintiffs and the state, the court issued an injunction requiring defendants to provide "only the minimum level of medical care required under the Eighth Amendment." However, three years after approving the stipulation as an order of the court, the court conducted an evidentiary hearing that revealed the continued existence of appalling conditions arising from defendants’ failure to provide adequate medical care to California inmates. As a result, the court ruled in June 2005 and issued an order on October 3, 2005 putting the CDCR's medical health care delivery system in receivership, citing the "depravity" of the system.[22] In February 2006, the judge appointed Robert Sillen to the position[23] and Sillen was replaced by J. Clark Kelso in January 2008.[24]

Coleman v. Brown is a federal class action civil rights lawsuit alleging unconstitutionally inadequate mental health care, filed on April 23, 1990. On September 13, 1995 the court found the delivery of mental health care violated the Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution, and issued an order for injunctive relief requiring defendants to develop plans to remedy the constitutional violations under the supervision of a special master.

Following the Governor's issuance of the State of Emergency Proclamation, the plaintiffs in Plata and Coleman filed motions to convene a three-judge court to limit the prison population. On July 23, 2007 both the Plata and Coleman courts granted the plaintiff's motions and recommended that the cases be assigned to the same three-judge court.[13] The Chief Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit agreed and, on July 26, 2007, convened the instant three-judge district court pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 2284.

As of 2008–09 fiscal year, the state of California spent approximately $16,000 per inmate per year on prison health care.[25] This amount was by far the largest in the country and more than triple the $4,400 spent per inmate in 2001.[26] The state with the second largest prison population in the country, Texas, spent less than $4,000 per inmate per year.[27]

Union: California Correctional Peace Officers Association

Officers of the department are represented by the California Correctional Peace Officers Association (the CCPOA). It was founded in 1957 and its stated goals include the protection and safety of officers, and the advocation of laws, funding and policies to improve work operations and protect public safety. The union has had its controversies over the years, including criticism of its large contributions to former California Governor Gray Davis. Since the California recall election, 2003, the CCPOA has been a vocal critic of Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger.

In June 2008, the union came under investigation from both the California Office of the Inspector General and the CDCR for its role in the hiring of a 21-year-old parolee by Minorities in Law Enforcement, an affiliate of CCPOA.[28] Upon conclusion of investigations by both agencies, no wrongdoing was found.

See also

National:

References

- ↑ "Table 1: Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for the United States, Regions, States, and Puerto Rico". U.S. Census Bureau. December 22, 2008. Retrieved January 15, 2009.

- ↑ California Department of Justice. California Criminal Justice Time Line 1822–2000. Accessed April 27, 2008.

- ↑ Reed, Dan. "Killer Location May Doom San Quentin Prison. Also Calling It Outdated, State to Consider Razing Infamous Bayside Penitentiary for Housing". San Jose Mercury News, August 20, 2001.

- 1 2 Corrections Independent Review Panel. Reforming Corrections. June 2004.

- 1 2 Governor Schwarzenegger Signs Legislation to Transform California's Prison System. Press release, May 10, 2005.

- ↑ Furillo, Andy. "Prisons plan shifts power to agency chief". Sacramento Bee, January 7, 2005.

- ↑ California Government Code 12838.5

- ↑ California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation Organizational Structure, October 2007. Accessed November 17, 2007.

- ↑ California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. Divisions and Boards. Accessed November 17, 2007.

- ↑ CDCR Division of Juvenile Justice. DJJ Facts, Stats & Trends - Summary Fact Sheet (January 2007). Retrieved December 1, 2007.

- ↑ CDCR Division of Adult Operations. First Quarter 2007 Facts and Figures. Retrieved December 1, 2007.

- 1 2 CDCR Division of Adult Institutions. Visitors Information Page. Retrieved November 30, 2007.

- 1 2 Moore, Solomon. New Court to Address California Prison Crowding". The New York Times, July 24, 2007.

- ↑ California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. California's Correctional Facilities Archived December 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.. October 15, 2007.

- 1 2 Travis, Jeremy, and Lawrence, Sarah. California's Parole Experiment. California Journal, August 2002.

- ↑ Moody, Shelah (December 9, 2007). "California Reentry Program gives ex-cons a second chance". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved January 12, 2009.

- ↑ "Correctional Officer Training". Department of Corrections & Rehabilitation. Retrieved April 27, 2008.

- ↑ The Officer Down Memorial Page February 2009

- ↑ Data Analysis Unit. "EMPLOYEES KILLED BY INMATES January 1952 through December 2011" (PDF). CDCR. Retrieved March 26, 2012.

- ↑ "History of Capital Punishment in California Archived July 24, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.." California Department of Corrections. Retrieved on August 16, 2010.

- ↑ "Court Ruling Won't Mean Bloodbath On Death Row". Associated Press at the Tuscaloosa News. Tuesday February 15, 1972. p. 10. Retrieved on Google News (6/15) on March 27, 2013. "There are five women under a sentence of death. Three of Manson's convicted accomplices, Susan Atkins, Leslie Houten, and Patricia Krenwinkel, are in a special women's section of the row built at the California Institute for Women at Frontera."

- ↑ Sterngold, James (July 5, 2005). "U.S. seizes state prison health care". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved December 21, 2007.

- ↑ Moore, Solomon (August 27, 2007). "Using Muscle to Improve Health Care for Prisoners". New York Times. Retrieved December 21, 2007.

- ↑ Kagan, Racheal (January 23, 2008). "CPR PRESS RELEASE: Judge Appoints New Prison Health Care Receiver, 01/23/08" (pdf). Retrieved February 9, 2008.

- ↑ "Overview of Adult Correctional Health Care Spending" (PDF).

- ↑ "State Prison Expenditures, 2001" (PDF).

- ↑ "Prison health update".

- ↑ Furillo, Andy. "Chief of CCPOA union, Mike Jimenez defends hiring of parolee".

External links

- Official website

- California Youth and Adult Corrections Authority (Archive)

- California Correctional Peace Officers Association

- California Reentry Program