Calciphylaxis

| Calciphylaxis | |

|---|---|

|

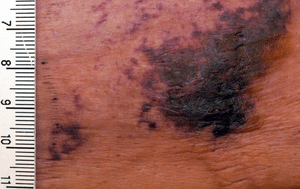

Calciphylaxis on the abdomen of a patient with end stage renal disease. Markings are in cm. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-9-CM | 275.49 |

| DiseasesDB | 1897 |

| eMedicine | derm/555 |

| MeSH | D002115 |

Calciphylaxis, or calcific uremic arteriolopathy (CUA), is a syndrome of vascular calcification, thrombosis and skin necrosis. It is seen mostly in patients with Stage 5 chronic kidney disease, but can occur in the absence of renal failure.[1] It results in chronic non-healing wounds and is usually fatal. Calciphylaxis is a rare but serious disease, believed to affect 1-4% of all dialysis patients.[2]

Calciphylaxis is one type of extraskeletal calcification. Similar extraskeletal calcifications are observed in some patients with hypercalcemic states, including patients with milk-alkali syndrome, sarcoidosis, primary hyperparathyroidism, and hypervitaminosis D.

Signs and symptoms

The first skin changes in calciphylaxis lesions are mottling of the skin and induration in a livedo reticularis pattern. As tissue thrombosis and infarction occurs, a black, leathery eschar in an ulcer with adherent black slough are found. Surrounding the ulcers is usually a plate-like area of indurated skin.[3] These lesions are always extremely painful and most often occur on the lower extremities, abdomen, buttocks, and penis. Because the tissue has infarcted, wound healing seldom occurs, and ulcers are more likely to become secondarily infected. Many cases of calciphylaxis end with systemic bacterial infection and death.[1]

Calciphylaxis is characterized by the following histologic findings:

- systemic medial calcification of the arteries, i.e. calcification of tunica media. Unlike other forms of vascular calcifications (e.g., intimal, medial, valvular), calciphylaxis is characterised also by

- small vessel mural calcification with or without endovascular fibrosis, extravascular calcification and vascular thrombosis, leading to tissue ischemia (including skin ischemia and, hence, skin necrosis).

Heart of Stone

Severe forms of calciphylaxis may cause diastolic heart failure from cardiac calcification, called heart of stone.[4]

Cause

The cause is not known. It does not seem to be an immune type reaction. In other words, calciphylaxis is not a hypersensitivity reaction (i.e., allergic reaction) leading to sudden local calcification. Clearly, additional factors are involved in calciphylaxis. It is also known as calcific uremic arteriolopathy; however, the disease is not limited to patients with kidney failure. The current belief is that in end-stage renal disease, abnormal calcium and phosphate homeostasis result in the deposition of calcium in the vessels, also known as metastatic calcification. Once the calcium has been deposited, a thrombotic event occurs within the lumen of these vessels, resulting in tissue infarction. It is unknown what the triggers are that cause the thrombotic and ischemic event.[5] Reported risk factors include female sex, obesity, elevated calcium*phosphate product, medications such as warfarin, calcium-based binders, or systemic steroids, protein C or S deficiency, hypoalbuminemia, and diabetes.[6]

Diagnosis

There is no diagnostic test for calciphylaxis. The diagnosis is a clinical one. The characteristic lesions are the ischemic skin lesions (usually with areas of skin necrosis). The necrotic skin lesions (i.e. the dying or already dead skin areas) typically appear as violaceous (dark bluish purple) lesions and/or completely black leathery lesions. They can be extensive. The suspected diagnosis can be supported by a skin biopsy. It shows arterial calcification and occlusion in the absence of vasculitis. Sometimes the bone scintigraphy can show increased tracer accumulation in the soft tissues.[7] In certain patients, anti-nuclear antibody may play a role.[8]

Treatment

The optimal treatment is prevention. Rigorous and continuous control of phosphate and calcium balance most probably will avoid the metabolic changes which may lead to calciphylaxis.

There is no specific treatment. Of the treatments that exist, none is internationally recognised as the standard of care. An acceptable treatment could include:

- Dialysis (the number of sessions may be increased)

- Intensive wound care

- Clot-dissolving agents (tissue plasminogen activator)

- Hyperbaric oxygen[9]

- Maggot larval debridement

- Adequate pain control

- Correction of the underlying plasma calcium and phosphorus abnormalities (lowering the Ca x P product below 55 mg2/dL2)

- Sodium thiosulfate

- Avoiding (further) local tissue trauma (including avoiding all subcutaneous injections, and all not-absolutely-necessary infusions and transfusions)

- Urgent parathyroidectomy: The efficacy of this measure remains uncertain although calciphylaxis is associated with frank hyperparathyroidism. Urgent parathyroidectomy may benefit those patients who have uncontrollable plasma calcium and phosphorus concentrations despite dialysis. Also, cinacalcet can be used and may serve as an alternative to parathyroidectomy.

- Patients who receive kidney transplants also receive immunosuppression. Considering lowering the dose of or discontinuing the use of immunosuppressive drugs in renal transplant patients who continue to have persistent or progressive calciphylactic skin lesions can contribute to an acceptable treatment of calciphylaxis.

Epidemiology

Calciphylaxis most commonly occurs in patients with end-stage renal disease who are on hemodialysis or who have recently received a renal (kidney) transplant. Yet calciphylaxis does not occur only in end-stage renal disease patients. When reported in patients without end-stage renal disease, it is called non-uremic calciphylaxis by Nigwekar et al.[10] Non-uremic calciphylaxis has been observed in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism, breast cancer (treated with chemotherapy), liver cirrhosis (due to alcohol abuse), cholangiocarcinoma, Crohn's disease, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Prognosis

Unfortunately, response to treatment is not guaranteed. Also, the necrotic skin areas may get infected, and this then may lead to sepsis (i.e. infection of blood with bacteria; sepsis can be life-threatening) in some patients. Overall, the clinical prognosis remains poor.

References

- 1 2 Wolff, Klaus; Johnson, Richard; Saavedra, Arturo. Fitzpatrick's Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology (7th ed.). McGraw Hill. p. 429. ISBN 978-0-07-179302-5.

- ↑ Angelis, M; Wong, LM; Wong, LL; Myers, S (1997). "Calciphylaxis in patients on hemodialysis: A prevalence study". Surgery. 122: 1083–1090. doi:10.1016/S0039-6060(97)90212-9. PMID 9426423.

- ↑ Zhou Qian; Neubauer Jakob; Kern Johannes S; Grotz Wolfgang; Walz Gerd; Huber Tobias B (2014). "Calciphylaxis". The Lancet. 383 (9922): 1067. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60235-X.

- ↑ Heart of Stone - CINDY W. T OM, MD,ANDDEEPAKR. TALREJA, MD. Division of Cardiovascular Diseases, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minn

- ↑ Wilmer, William; Magro, Cynthia (2002). "Calciphylaxis: Emerging Concepts in Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment". Seminars in Dialysis. 15 (3): 172–186. PMID 12100455.

- ↑ Arseculeratne, G; Evans, AT; Morley, SM (2006). "Calciphylaxis – a topical overview". Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 20: 493–502. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01506.x. PMID 16684274.

- ↑ Araya CE, Fennell RS, Neiberger RE, Dharnidharka VR (2006). "Sodium thiosulfate treatment for calcific uremic arteriolopathy in children and young adults". Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 1 (6): 1161–6. doi:10.2215/CJN.01520506. PMID 17699342.

- ↑ Rashid RM, Hauck M, Lasley M (Nov 2008). "Anti-nuclear antibody: a potential predictor of calciphylaxis in non-dialysis patients". J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 22 (10): 1247–8. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02606.x.

- ↑ Edsell ME, Bailey M, Joe K, Millar I (2008). "Hyperbaric oxygen therapy in the treatment of skin ulcers due to calcific uraemic arteriolopathy: experience from an Australian hyperbaric unit.". Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine. South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society. 38 (3): 139–44. Retrieved 2013-04-02.

- ↑ Nigwekar SU, Wolf M, Sterns RH, Hix JK (Jul 2008). "Calciphylaxis from nonuremic causes: a systematic review". Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 3 (4): 1139–43. doi:10.2215/cjn.00530108.

External links

- Weenig RH (2008). "Pathogenesis of calciphylaxis: Hans Selye to nuclear factor kappa-B". J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 58 (3): 458–71. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.12.006. PMID 18206262.

- Weenig RH, Sewell LD, Davis MD, McCarthy JT, Pittelkow MR (2007). "Calciphylaxis: natural history, risk factor analysis, and outcome". J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 56 (4): 569–79. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.08.065. PMID 17141359.

- Li JZ, Huen W (2007). "Images in clinical medicine. Calciphylaxis with arterial calcification". N. Engl. J. Med. 357 (13): 1326. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm060859. PMID 17898102.

- DermNet NZ: Calciphylaxis

- Calciphylaxis Registry

- German Calciphylaxis Registry: www.calciphylaxie.de