Cainites

| Part of a series on | |||

| Gnosticism | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| History | |||

| Proto-Gnostics | |||

| Scriptures | |||

|

|||

| Lists | |||

| Related articles | |||

The Cainites, or Cainians (Greek: Καϊνοί Kainoi, Καϊανοί Kaianoi),[1] were a Gnostic and Antinomian sect who were known to venerate Cain as the first victim of the Demiurge, the deity of the Tanakh, who was identified by many groups of Gnostics as evil. The sect following was relatively small. They were mentioned by Tertullian and Irenaeus as existing in the eastern Roman Empire during the 2nd century. One of their purported religious texts was the Gospel of Judas.

History

The oldest source is to be found in Irenaeus, adv. Haer. i. 31.

Cain and Abel

He tells us that the Cainites regarded Cain as derived from the higher principle. They claimed fellowship with Esau, Korah, the men of Sodom, and all such people, and regarded themselves as on that account persecuted by the Creator. But they escaped injury from him, for Sophia used to carry away from them to herself that which belonged to her.

Epiphanius (Haer. 38) characteristically gives a much longer account, in substantial harmony with what Irenaeus says. He appears to have had some source of information independent of Irenaeus. He speaks of Abel as derived from the weaker principle—a statement which bears the marks of authenticity.

Redemption

The account given by Irenaeus is unduly curt and the text not quite secure, but it is not difficult to form a general estimate of the sect from it, especially with the assistance of our other sources. Like other Gnostics, the Cainites drew a distinction between the Creator and the Supreme God. They identified the Creator with the God of the Jews. They viewed him and those whom he favoured with undisguised hostility; redemption had for its end the dissolution of his work. They claimed kinship with those to whom he showed antagonism in his book, the Old Testament, and shared themselves in the same hostility. Nevertheless, he was the weaker power, who could do them no permanent harm, for Sophia, the Heavenly Wisdom, drew back to herself those elements in their nature which they had derived from her.

Presumably, then, they thought of a division of mankind into two classes—the spiritual and the material, the latter belonging to the realm of the Creator and deriving their being from him, but doomed to dissolution, while the former class contained the spiritual men, imprisoned, it is true, in bodies of flesh, but yet deriving their essential being from the highest Power, opposed by the Creator and his minions, but winning the victory over them as Cain did over Abel.

Judas

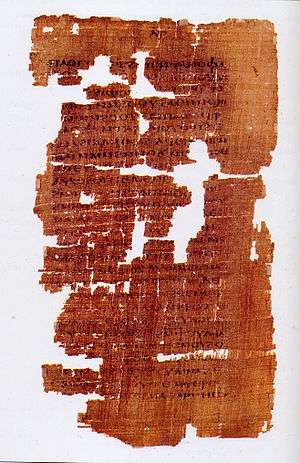

They regarded Judas the traitor as having full cognizance of the truth. He therefore, rather than the other disciples, was able to accomplish the mystery of the betrayal, and so bring about the dissolution of all things both celestial and terrestrial. The Cainites possessed a work entitled The Gospel of Judas, and Irenaeus says that he had himself collected writings of theirs, where they advocated that the work of Hystera should be dissolved. By Hystera they meant the Maker of Heaven and Earth.

Epiphanius also says that Judas forced the Archons, or rulers, against their will to slay Christ, and thus assisted us to the salvation of the Cross. Philaster, on the other hand, assigns the action of Judas to his knowledge that Christ intended to destroy the truth—a purpose which he frustrated by the betrayal.

There is no doubt that they applauded the action of Judas in the betrayal, but our authorities differ as to the motive which prompted him. The view that Judas through his more perfect Gnosis penetrated the wish of Jesus more successfully than the others, and accomplished it by bringing him to the Cross through which he effected redemption, is only one of them.

Transmigration

So far as the moral character and conduct of the Cainites is concerned, there is no doubt that Irenaeus intended to represent them as shrinking from no vileness, but rather as deliberately practising it. He states that they taught, as did Carpocrates, that salvation could be attained only by passing through all experience. Whenever any sin or vile action was performed by them, they asserted that an angel was present whom they invoked, claiming that they were fulfilling his operation. Perfect knowledge consisted in going without a tremor into such actions as it is not lawful even to name.

Carpocrates, we are told, defended this practice by a theory of transmigration. It was necessary to pass through all experiences, and hence the soul had to pass from body to body till the whole range of experience had been traversed. If, however, this could all be crowded into a single lifetime, then the transmigration became unnecessary. We have no ground to suppose that the Cainites held such a view, but they seem to have professed the belief that this fullness of experience was essential to salvation. We have no substantial justification for doubting the truth of Irenaeus' account, though accusations of immorality urged against heretics should always be received with caution. G.R.S. Mead (Fragments of a Faith Forgotten, 1900, p. 229) thinks that originally they were ascetics, while N. Lardner (History of Heretics, bk. ii. ch. xiv. [= Works, 1829, viii. 560]) questions whether a sect guilty of such enormities ever existed. But there is no valid reason to deny the generally accepted view that the Gnostic attitude to matter did lead to quite opposite results. To some it would seem a duty to crush the flesh beneath the spirit by the severest austerity, but the premise might lead to a libertine as well as to an ascetic conclusion.

Source texts on the Cainites

- Irenaeus, Against Heresies 1.31.1–2

- Epiphanius of Salamis, Panarion 38

- Hippolytus, Against Heresies 8

- Pseudo-Tertullian, Against All Heresies 7

- Tertullian, On Baptism 1.

Other meanings

- Cainites is a term used by some adherents of Christian Identity groups to insult Jews.

- Cainites is an alternate transliteration for Kenites.

- Cainite theology is discussed in the 1919 Hermann Hesse novel, Demian.

In popular culture

- The Cainites are referred to in issue 22 (May 1990) of Sandman, a comic published by DC Comics and written by Neil Gaiman. The description of the sect is inconsistent with this entry's description.

- In White Wolf, Inc.'s Vampire: The Masquerade universe (also known as the World of Darkness) storyline, Cainites is another name for Vampires i.e.: those descended from Cain (the first vampire). The description of the sect is inconsistent with this entry's description.

- The book Demian, by Hermann Hesse, extensively draws upon the beliefs of the Cainite sect. The eponymous character Max Demian even convinces the protagonist Emil Sinclair that Christianity had misunderstood Cain's virtue over Abel's.

- In The Hundred Days, 19th in Patrick O'Brian's Aubrey-Maturin series: Dr. Amos Jacob, an expert on North African languages and customs, becomes Maturin's assistant surgeon and intelligence officer. Amongst other connections, he belongs to the esoteric cult of Cainites; ancient and declining but still extant throughout the Mediterranean. The plot turns on Dr. Jacob's serendipitous recognition of a fellow member by their shared, secret "mark of Cain."

- The Cainites, led by Tubcal-Cain, are the main antagonists of Noah.

- In Assassin's Creed, Cain was the first Templar, making the Templars his spiritual successors if not genetically Cainite, and the Mark of Cain is actually the Templar Cross.

See also

Notes

- ↑ The name is variously written; Καϊνοί (Hippol. Ref. viii. 20; Theodoret, Haer. Fab. i. 15); Caini (Praedest. Cod.); Καϊανισταί (Clem. Alex. Strom. vii. 17), Καϊανοί (Epiphanius, Haer. 38; Origen, contra Celsum, iii. 13, but his translator Gelenius gives Cainani); Caiani (Philast. 2; Augustin. Haer. 18, Praedest. 18, codd.); Gaiana haeresis (Tertullian de Praescrip. 33, and de Bapt. 1), but Jerome writing with a clear reference to the latter passage of Tertullian has Caina (Ep. 83, ad Oceanum, and contra Vigilantium). Elsewhere he seems to have Cainaei (Dial. adv. Lucifer. 33); but many MSS. here have Chaldaei. So also Cainaei (Pseudo-Tertullian, 7), Cainiani (Praedest. Codd.). Irenaeus (i. 31) describes the doctrines of the sect, but gives them no title.

Bibliography

- Attribution

This article incorporates text from a work in the public domain: Peake, Arthur S. (1919). "Cainites". In Hastings, James; Selbie, John Alexander; Lambert, John Chisholm. Dictionary of the Apostolic Church. Volume I. New York: C. Scribner's Sons. pp. 165–6.

This article incorporates text from a work in the public domain: Peake, Arthur S. (1919). "Cainites". In Hastings, James; Selbie, John Alexander; Lambert, John Chisholm. Dictionary of the Apostolic Church. Volume I. New York: C. Scribner's Sons. pp. 165–6. This article incorporates text from a work in the public domain: Salmon, George (1877). "Cainites". In Smith, William; Wace, Henry. A Dictionary of Christian Biography, Literature, Sects and Doctrines. Volume I. London: John Murray. pp. 380–2.

This article incorporates text from a work in the public domain: Salmon, George (1877). "Cainites". In Smith, William; Wace, Henry. A Dictionary of Christian Biography, Literature, Sects and Doctrines. Volume I. London: John Murray. pp. 380–2.